Shutting down Tavistock gender clinic is not the victory the Right thinks it is.

When it was announced on Thursday that the NHS will be shutting down a children’s gender identity development service (not a noun I ever thought I would use), the Sophie Corcorans of the world jumped onto Twitter claiming this as a victory in keeping children away from trans ideology. However, what those so keen to jump on the celebratory bandwagon fail to recognise is that the reason that this clinic is being shut down is not because it was over-providing its services, but the fact that it was seen to be under-providing them.

While there have been some concerns raised about the overdiagnosis of gender dysphoria, the main reason for the service being shut down has been due to concerns of under provision. The number of referrals to gender specialists across the country has increased from around 140 in 2010, to around 2,300 in 2020. Whereas in the past gender dysphoria mostly affected men who believed themselves to be women, the inverse is now true, and much of the additional referrals come from teenage girls; the same group who are targeted by all others who seek to create a groupthink craze. These stretch from the relatively harmless, like One Direction fans back in the day, to the magazines promoting anorexia in the 90’s – and in the true spirit of throwing the baby out with the bathwater – the same publications now using Tess Holloway to promote ‘health at any size’.

Because of the immense increase in referrals, waiting times to be seen at Tavistock are now five years. According to Hillary Cass, who was tasked with reviewing the service and writing a report which was published this spring, the service was under ‘unsustainable pressure’, with the long wait times causing patients considerable ‘distress’ and ‘declining mental health’. While the right picked up the quote that the clinic was ‘not safe’ for children, they failed to see that the reason this was claimed is that their supposed needs were being ignored, as opposed to being sated.

What this argument seems to ignore is that long wait times are good and necessary when dealing with children with no medically urgent needs. Given the number of young adults seeking to de-transition (aka reverse the alterations done to their bodies during their adolescence), forcing those seeking such services to have a long wait period to consider the permanence and impact of such a decision is an entirely sensible policy. In accordance with the government’s focus on levelling up, a new network of ‘regional hubs’ is being planned to replace Tavistock, despite the fact that for someone in Birmingham or Manchester seeking such a service, the need to make a trip to London may make them consider whether or not their reasons for doing so are legitimate.

However, the long wait times that have been tacit government policy for decades (and quite successfully, given the negligible numbers of de-transitions until very recently) are now being undermined by private providers with even fewer scruples than the NHS. Given that upper middle-class children of guardian-reading intellectuals are most likely to want to transition in the first place, there has been an increase in private provision of cross sex hormones and surgery, as well as an increase in people going abroad for cheaper surgeries. In order to gain the Brownie points of ‘supporting their trans child’, the parents will do whatever is necessary to fast-track their child’s transition without giving them the chance to change their mind.

In conclusion, shutting down Tavistock is not a victory for conservatives but a loss. The ideologically driven medicine that was once contained in London for those determined enough to make the journey will now be spread out across the country in order to reach more and more children. If the government keeps allowing supply to grow to keep up with the supposed demand, we will end up with a generation where fewer and fewer young people have healthy bodies, and even fewer with healthy minds. However, the worst offenders in creating this contagion among young girls is TikTok and an educational culture which defines its role as helping children ‘unlearn’ their biases, as opposed to learning the realities of the world: until this changes, nothing will.

You Might also like

-

Another Organization? Splendid!

Popular Conservatism (PopCon) has just launched and it’s about as popular as booting a crippled dog into oncoming traffic. Spearheaded by Liz Truss, the shortest serving Prime Minister in British political history and the most unpopular Conservative politician in the country, the organization is begging to be ridiculed by the media and the public.

However, whilst Truss is the face of the group, the organization is directed by Mark Littlewood, former director general of the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), a pro-immigration think-tank. Like Truss, Littlewood is a former Liberal Democrat, serving as director for Liberal Vision, a group of economic liberals within the party. Unlike Truss, he’s a former of the Pro-Euro Conservative Party (PECP), a minor offshoot of the Tories which campaigned for Britain to adopt the Euro and oust then-leader William Hague in favour of arch-Europhile Kenneth Clarke. After the dissolution of the PECP, Littlewood became an advisor to the Conservative Party under the leadership of David Cameron.

Earlier in life, Littlewood worked for the European Movement, an all-party group campaigning for British membership of a federalised Europe; Liberty, the human rights advocacy group which spearheaded campaigns to implement and maintain the Human Rights Act; and NO2ID, a group which campaigns against the introduction of ID cards.

So, what does Popular Conservatism stand for? Apparently, its aims are: “inform and educate candidates and MPs about the need to reform Britain’s bureaucratic structures” and “advance these policies across the country, whilst demonstrating their popularity.”

According to Littlewood, PopCon is about: “Giving ordinary people, taxpayers and voters, their freedom back. That was what Brexit was supposed to be about: taking back control.”

Taking Back Control? Why would Littlewood care about Taking Back Control? Littlewood changed his view on EU integration at the time of the referendum, writing in a personal statement:

“Twenty years ago, I was a passionate and enthusiastic supporter of European integration. I was President of the UK branch of the Young European Federalists in 1996 and my first job was working for the European Movement. I was enthusiastic about the UK joining the single currency and I even supported the Pro-Euro Conservative Party, a breakaway from the Conservatives on the issue of Britain’s relationship with the EU.

“Since then, and bit by bit, my thinking has evolved and the European Union, in my judgment, has increasingly become a force for heavy handed and petty regulation rather than for free market liberalism. The EU is no longer the deregulatory single-market it once aspired to be. Instead, it has become a monolithic and increasingly interventionist bureaucratic super-state. After considerable thought – and with a heavy heart – I have reached the conclusion that Britain would be best advised to leave the EU and I will be voting accordingly on 23rd June.“I believe there are risks and uncertainties involved in going for Brexit, but these are – on balance -risks worth taking. There is no guarantee that Britain will become a more outward-looking, globally free trading, open and free society outside of the EU. But there is, in my view, a pretty good chance of it.”

In summary, Littlewood’s euroscepticism (and by extension, the bent of PopCon’s brand of politics) is rooted in the belief the EU (much like the UK, presuambly) has become too protectionist, too nationalist, too conservative and too isolationist, hindering Britain’s ability to push ahead with economic and cultural globalisation. In the government’s own words:

“Global Britain is about reinvesting in our relationships, championing the rules-based international order and demonstrating that the UK is open, outward-looking and confident on the world stage.”

This aspiration, typically referred to as “Global Britain”, is uncommon amongst Brexiteers generally, but quite popular with a narrow clique of largely London-centric free-marketeers, comprised largely of Tory staffers, centre-right policy wonks, disgruntled civil servants, conservative commentators, and Thatcherite MPs. GBNews’ Tom Harwood, former Chair of Students for Britain, summarises the disposition of this demographic briefly but well: “open globalism, not narrow regionalism”. That’s right, we’re the real cosmopolitan internationalists, the left are the real provincialists!

As many will remember, “Global Britain” was announced as the official post-Brexit endeavour of the Conservative governments of Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Liz Truss, albeit the first and second were over-encumbered by the withdrawal process and Covid to implement many of their desired reforms – besides, of course, importing an unprecedented number of immigrants. Consequently, whilst Boris was intended as the figurehead for Global Britain, the role ultimately fell to Liz “Boris 2.0” Truss.

For clarity, there is nothing particularly radical about “Global Britain”. It has always been the Menshevik position within the Brexit coalition. Throughout the referendum it was occasionally used as a polemical tactic (i.e. Let’s Go WTO), but nothing more. Contrasted to the Bolshevik aspiration of turning Britain into an island fortress, derided by Britpoppers as “Little England”, the Menshevik aspiration is to turn Britain into a mass financial district, in which vampiric multinationals terrorise Middle England from above and an imported underclass of cheap labour, violent criminals, and ethnic displacement terrorises it from below.

Of course, it’s colossally terrible but it’s not too dissimilar to the relatively liberal arrangement we had before Brexit and certainly no different to the arrangement we have now. Alas, this doesn’t stop PopCons from complaining the system is stacked against efforts at economic liberalisation. Yes, the planning system is needlessly complicated, but there’s no need for hyperbole; weaning people off microplastics and ultra-processed food isn’t Soviet.

Essentially, both Global Britain and PopCon are tendencies born out of the ideas contained in Britannia Unchained, a book which seeks to answer the question on everyone’s mind: “How can we get white British people to work more for less and demographically replace them in the process?”. Making immigration uncontroversial by making it productive, saying NO to identity politics, saying NO to the Nanny State, Getting On Your Bike, STEM, India Superpower 2020, Peace… through Commerce. Real Tory Boy stuff.

This leads into another problem with PopCon. It isn’t just its initial unpopularity, it has no idea how to be popular, despite the fact the answers have been in plain sight for years. Boris Johnson’s popularity peaked when he promised to end immigration and shouted “Fuck Business” to a Belgian diplomat. Theresa May, a completely unknown and irrelevant politician, reached unprecedented levels of popularity after the referendum when she was attacking “citizens of nowhere” to such an extent she was being compared to Adolf Hitler. David Cameron reached the height of his popularity when he was promising to reduce immigration and hold a referendum on the EU, threatening to leave the ECHR, and declaring state multiculturalism to be a failure.

Compare this with Liz Truss. In her historically brief tenure, she tried to pursue free movement and trade with India and borrow billions to fund tax cuts for the rich. Suella Braverman, for all her many faults, understood during her leadership bid that leaving the ECHR and stopping illegal immigration are popular with the public, especially with voters in the Red Wall – policies which PopCon lightly sprinkled into their otherwise bland, derivative, and highly ironic attempt at wrapping Orange Book Liberalism in a flag.

Flip-flopping seemed to be an integral theme of the PopCon event. As established, Littlewood and Truss are former Lib Dems, but Anderson is former Labour, Farage was pivoting back and forth between endorsement and dismissal throughout the whole thing, and Holly Valance gave an unrelentingly generic interview stating life is about being left-wing, making money, and then moving rightwards.

This obsession with switching is bizarre, but it’s the recurring tendency one should expect from an organization which simultaneously fights for the so-called “rules-based international order” and complains about an arbitrary global humanitarian class undermining national democracy; fronted by a former Prime Minister and her group of orbiters who’ve done nothing in their 14 years of government to address any of the problems their organization hopes to “inform and educate” us about.

PopCon doesn’t seem to understand that some of us have been aware of the Great Replacement, Cultural Marxism and The Blob since secondary school. We don’t need to be told that some people think there are more than two genders or that state-funded charities and quangos are jampacked with people who hate our country; we don’t need to be told liberal-left ideas and values are hegemonic, or that illegal immigrants take advantage of the welfare system. We are children of the revolution, for Christ’s sake!

All the way down, PopCon is a group for people to scratch their heads at problems they have helped to create, assuming nobody else has identified them before, and offer milquetoast solutions with the galling expectation of jubilant applause.

It is slightly comical. 2030 will arrive and Liz Truss will be explaining the drawbacks of the sexual revolution and quoting G.K Chesterton. Erstwhile, MechaBlair will be conscripting masses of young White British men to fight Populism in Ukraine and organizing taxpayer-subsidised migrant mega-orgies in The North. Indeed, trying to make political progress with the present batch of Conservative MPs is like trying to scale Mount Everest with Stephen Hawking; it’s really quite demoralising.

Whilst Donald Trump is saying immigrants “poison the blood” of America, whilst Germany’s AFD is advocating mass remigration, whilst France’s Eric Zemmour is openly discussing demographic displacement, the British right is forced to contend with another attempt to rehabilitate Thatcherism, another attempt to undercut the emergent nationalist, protectionist, and socially conservative elements of the right which have been trying to take root in established positions since the referendum; another perversion of the anti-immigration spirit of Take Back Control (TBC), framed in terms of mere economic and legal technicality, adorning it with another SW1-friendly signifier to go with the rest: TBC as a vote for liberalism, as a call for localist devolution, as a general dislike of politicians, as a mere symptom of economic turbulence, as a nationwide Freudian psychodrama.

Despite all of this, despite my complete contempt for PopCon, I’m glad it exists. In all sincerity and without a hint of contrarianism. PopCon is bad because it’s Tory-branded Globalism run by Thatcherite Zombies without a hint of self-awareness, creativity, or charisma, not because it’s “another organization” – a complaint I’m absolutely sick of hearing from supposedly disaffected voices.

At present, Britain doesn’t have a political culture, but it wasn’t always this way. Indeed, some people (mainly our anti-political overlords and pseudo-Anglos within and adjacent to our circles) have espoused the notion that political organization is somehow terribly un-English. However, a brief glance at history tells us that beneath gentle-mannered disposition (some might say caricature) of the native population, political organization, rowdiness, and militancy – even outright violence – have existed for several hundred years in this country, boiling beneath the surface of even standard parliamentary exchanges.

The snobbish anti-partisanship of those who are disgruntled by the lack of action but see themselves above political organization are an abject cancer. Everyone has remarked that MPs enter Parliament to immediately do something else, whether it’s charity work or presenting a TV show, but few have surmised what this means. It shows that power is contingent on the wider superstructure of society; the Overton Window must be adapted so political objectives can fully actualise themselves and legislated into reality, something the enemies of Britain have done and are currently doing very well.

As such, we don’t need less organization or less division, we need more. More organization, more division, more militancy, more enmity, more ideology, more partisanship, more coups, more activism, more conflict, more metapolitics of every form and variety. Let the Darwinian selection processes of the political run wild; radicalise democracy against every rendition of liberalism and rejoice as it stampedes over the latter’s mangled corpse. No, PopCon doesn’t deserve to fail… it deserves to be killed.

Post Views: 377 -

With Friends Like These, Who Needs Enemies?

Several months have passed since Hamas orchestrated the surprise attacks against Israel in the notorious and brutal events of October 7th, one of the bloodiest days in Israel’s modern history, with over a thousand people killed or kidnapped by Hamas – consequently launching the war in Gaza, and the prolonged campaign of Netenyahu’s government against Hamas and its supporters.

Needless to say, the Israeli response to such an outrageous and devastating attack against civilians has been swift. Combined strategic responses of aerial bombardments, drone strikes, and ground forces swelling into Gaza have been unrelenting, like a jackhammer.

Since October 7th, and the resulting war that followed, social media has erupted with images and videos coming out of Gaza detailing the quite dire humanitarian crisis currently occurring. It’s hard to estimate how many civilians have been killed during the war, but it is likely within the tens of thousands, with more and more adding to the body count as each day passes.

The position of Gaza has also made the situation even more difficult to control, as civilian aid is becoming harder and harder to access through narrow strategic corridors and lack of proper organization and distribution. Vital resources like food, water, and medicine aren’t ending up in the hands of the people that need it the most – if the bombs and the bullets don’t kill the people on the ground, the lack of resources will.

The shock and fury felt across the world after being confronted with this crisis has become a key issue in the West, with countless organized protests at universities and in the streets of capital cities, all demanding that Western nations stop funding the Israelis as they continue their military campaign in the heart of Gaza. This pro-Palestine movement, which is quite broadly supported by those with left-leaning ideologies and intersectionalists, has become an impressive political bloc – especially since it is an election year for both Great Britain and the United States.

Which is frankly quite funny, as most of the people in the pro-Palestine camp, chanting the mantras and songs of Hamas would be shunned by the very same groups they feel the need to protect. In fact, many already have.

Meanwhile, especially amongst “Christian conservatives” in the media and online, there has seemingly been a blank check of support given towards Israel – especially Netenyahu and his Likud government.

After all, Hamas is a terrorist organization, and anything that stops Islamic fundamentalist terror is worth supporting, right? We simply have a moral duty to support Israel, regardless of how blatantly horrific the situation is on the ground. Tax dollars and civilian casualties are a small price to pay for FREEDOM and the protection of “Judeo-Christian” values.

It’s exhausting, but no matter which way you look at it, this will be a defining political issue for the next decade, if not even longer.

And, as always, instead of being able to approach the issue with any level of nuance or recognition that both sides in this conflict seem to be as equally awful and hostile to us as they are to each other, we will once again be put into this binary choice of being “with” or “against” either side. The arguments will be circular, and the cycle of destruction will continue while only a handful of people end up benefiting – mainly weapons contractors and political donor groups.

Before I jump into the beef of this piece, I want to express my outright condemnation of terrorism and terror groups. I feel as if I am obliged – although I think it’s entirely self-evident – to say this, because undoubtedly there will be those who take what I have to say next as an endorsement of Hamas or other fundamentalist Islamic radicals in their war against the State of Israel.

It isn’t. Read the last two paragraphs again if you are confused about where I stand on this issue.

So now that terrorism has been condemned, let’s continue to condemn and reevaluate our unconditional alliance with Israel; because frankly their accusations against Hamas and Palestine is a case of the pot calling the kettle black.

Don’t believe me? I doubt many have had the chance to delve deep into this issue, so let’s start with a little history lesson, shall we?

To understand the Israel of today, you don’t just go back to the partition of Palestine and founding of the State of Israel in 1947, you have to go back a little further in the century, back when the land we now know as Israel was a part of the Ottoman Empire.

Back at the start of the 20th century, when the world was rapidly changing, and revolutionary attitudes were spreading like wildfires, small groups of militias and rebels were beginning to emerge in Palestine.

“In fire and blood did Judea fall; in blood and fire Judea shall rise” was the motto of the group known as Bar-Giora (later “Hashomer”).

Originally this paramilitary organization’s goal was to defend Jewish settlements in the Ottoman Empire from attacks by local Arab populations.

Seems noble enough at first glance, and perhaps it was in intention, but this paramilitary organization, which was led by young, often Marxist-aligned rebels, did not just intend to play defense, but rather grow strong enough and large enough that they could create an effective offense against their Arab neighbors. And judging by their slogan, one can piece together that they weren’t exactly willing to compromise or negotiate peacefully in order to fulfill their goals of establishing permanent Jewish settlements in the region.

After World War One, as the British took control of Palestine, thus leading many members of Bar-Giora/Hashomer to join the Jewish Legion of the British Army in Palestine, as well as assuming positions in the local, British-backed law enforcement.

During the Arab riots of 1920-21, many Jewish settlements and Palestinian Jews suffered attacks at the hands of Palestinian Muslims. Believing that the British were unwilling, or unable, to confront the Muslim majority, these now formally-trained soldiers splintered off and founded “Haganah”.

Haganah went from being a rather unorganized militia to a funded, armed, and large underground army within a matter of years, and would serve as the foundation for what we see as the IDF today.

Again, while noble in intentions – to protect Jewish settlements – you’re only as good as the bad apples in the basket. It didn’t take long for splinter groups to form out of Haganah, namely Irgun, Palmach, and Lehi.

These groups all had a common resentment towards the British authorities – especially because of the White Paper declarations in 1922 and 1939 that sought to limit the amount of Jewish Europeans emigrating to Palestine, in order to not disrupt relations with the local Palestinians and allow for a slow-bleed assimilation of Jews into the region.

An idealistic approach, and perhaps a fool’s venture – but given the current state of things in the region, I’m sure the policymakers of the Empire had good reason to do so.

Palmach was a more formidable armed force, which was allied with the British in WWII and fought against Axis powers in the region. Eventually, after the war, the British ordered that the independent Palmach was disbanded, but operations simply moved underground, and Palmach found a new enemy with the British Mandate – they conducted several operations, including bridge bombings and night-time raids, against British assets in the region – all in response to the White Paper policies.

Irgun started in the late 1930’s as an offshoot of Haganah, and much like Haganah was initially a defensive force. However, after a prolonged period of Arab attacks and Irgun-conducted reprisals, the organization became more focused on arming, training, and conducting operations against anyone deemed a threat – this included the British authorities, who were trying to control the anarchy and fighting that was constantly breaking out in Palestine between factions of Jews and Arabs.

Lehi was founded by Yair Stern as a splinter of Irgun, and was composed of the more radical and violent Zionists of the time – some of whom even sought alliances with Hitler and Mussolini as they saw the British as a larger threat to their existence. They were self-described terrorists, as outlined in their underground newspaper, He Khazit;

Neither Jewish ethics nor Jewish tradition can disqualify terrorism as a means of combat. We are very far from having any moral qualms as far as our national war goes. We have before us the command of the Torah, whose morality surpasses that of any other body of laws in the world: “Ye shall blot them out to the last man.”

Charming mantra, to say the least.

Now, let’s take a look at a couple of notable examples of Zionist terrorism at the time, such as the King David Hotel Bombing.

The attack, which took place in July 1946, was carried out because the hotel was the headquarters of the central offices of the British Mandatory authorities of Palestine, as well as the British Army in the region. The bombing was in retaliation of the British conducting search and seizure operations of arms against the Jewish Agency in Palestine and to stop Palmach sabotage operations.

This attack claimed the lives of 91 people – Arabs, Jews, and indeed Britons – as well as injuring 46 others.

Another example, shall we?

The Deir Yassin Massacre – April 9th, 1948. Igrun and Lehi fighters raided the village of Deir Yassin in the morning, killing civilians with hand grenades and guns, indiscriminately. Around 110 villagers, including women and children were killed in the attack – some of whom were kidnapped and paraded in the streets of West Jerusalem before being executed.The village was then seized, the rest of the villagers expelled, and the village was renamed Givat Shaul.

How about political assassinations?

Walter Guinness, The Lord Moyne, was shot and killed in Cairo along with his chauffeur on the 6th of November 1944 by two members of the Lehi terrorist organization. Guinness was targeted as he was seen as responsible for Britain’s policy in Palestine, and was accused of being sympathetic to the Arabs.

Or, Folke Bernadotte – Swedish diplomat and a man who almost single handedly negotiated the release of 450 Danish Jews and thousands of other prisoners from the Theresienstadt Concentration Camp during WWII. Folke was appointed to be the UN Security Council’s mediator for the Arab-Israeli conflict, and was shot and killed by Lehi members while conducting his duties to end the conflict.

There are many, many more examples of explicit acts of terrorism, targeted assassinations, kidnappings, and other quite ghastly actions conducted by these radical Zionist groups, but now I think it would be constructive to see the legacy that these groups left, and a few notable Israelis were sympathetic, or a part of these organizations.

After the assassination of Folke Bernadotte, Lehi was formally disbanded and its members were arrested by the now established State of Israel. Happy ending, right? Wrong!

Lehi members were given a general amnesty right before the 1949 election, and in 1980 the Israeli government commissioned a military decoration named after the group, called the Lehi Ribbon, an “award for activity in the struggle for the establishment of Israel”.

Irgun, the group responsible for the King David Hotel bombing, was absorbed into the newly created IDF in 1948. While the paramilitary organization was formally disbanded in 1949, its members would later become the founders of the Herut Party – Herut would later merge into the Likud Party, one of the largest political parties in Israel, and the party that currently holds power.

David Ben-Gurion, 1st Prime Minister of Israel, supported the bombing of the King David Hotel, although later he publicly condemned it. While Ben-Gurion was a leader of the Jewish Agency, he did little to help the British in stopping the operations of Lehi and Irgun.

Menachem Begin, 6th Prime Minister of Israel, was an active member of Irgun, and became a commander of the terrorist organization in 1943. He was the founder of the Herut Party in 1948 (which later became known as “Likud”).

Yitzhak Shamir, 7th Prime Minister of Israel, was a leader of the Lehi terrorist group during its operational years. Shamir was responsible for plotting the assassination of Lord Moyne, and of Folke Bernadotte during his tenure as the leader of Lehi. In 1955, he joined Mossad, where he orchestrated Operation Damocles – targeted assassination of German rocket scientists assisting Egypt’s missile program.

Fascinating, to say the least. Some absolutely dreadful people, who ended up in the highest office of their country, and, somehow, allied with Britain, the very power they sought to expel from their nation. I can only imagine how awkward those Israeli meetings with the various Prime Ministers of the UK must have been – that is, of course, if those Prime Ministers had actually known or cared about what crimes these people were responsible for, and the British blood that they shed in order to achieve their goals.

Because, fundamentally, this nation is hostile. Not only to its immediate neighbors in the Middle East, but to us in the West as well.

Does anyone in their right mind think that almost a century of ideology, propaganda and leadership by vehemently anti-British, and by extension anti-Western political figureheads and former terrorists somehow is just washed away with time?

It is ludicrous that somehow, the political party that is in power, which was founded by the very terrorists who conspired and successfully carried out attacks against the British, has simply forgotten or somehow changed its foundational core values.

These roots run deep – and by observing the current administration of the Israeli government, we can see that the most important positions are occupied by hardcore, uncompromising Zionists who undoubtedly share the same values as their predecessors.

If this was an issue which was only relegated to the Middle East, I doubt anyone in the West would need to care. But unfortunately, due to the billions of dollars of donations from Israeli-aligned political groups, the billions of dollars of weapons deals done with Israel, and the overindulgent culture of philo-Semitism in Western governments, we in the West are unfortunately tethered to this country, its issues, and the repetitive cycle of destruction and death that it generates.

We are told that we have a moral obligation to support Israel, out of vague notions of protecting the “only functional democracy in the Middle East”, or through beating the drum of Holocaust guilt that, somehow, if we don’t stand by Israel and its campaigns of “self-determination” (i.e. constant expansion) we are somehow antisemites and no better than the Nazis.

Our governments even flirt with, if not having already passed legislation, that will limit our free speech in our countries if we dare criticize the Israelis for taking their war and destruction against a severely outgunned Palestine as being a little too far. The United States House just recently passed a bill that would severely curtail the ability to criticize Israel and its actions, under the guise of trying to stop anti-semitism on college campuses.

Especially on the cusp of important elections in the UK and the United States, how can any patriotic, nationally-minded voter bring themselves to the ballot box and vote for politicians and parties that are so explicitly Zionist that they take their mandatory trip to the Wailing Wall as soon as they are elected for a photo op and a corny declaration of allegiance to a foreign nation?

So here we are. Our fates tied to the ambitions of a small nation in the desert. While they continue to expand violently and push outward, as was the vision of the founders of their country, we in the West are meant to just sit back, and fork over our tax dollars to let it happen over some very unclear obligation that we are told we have.

Israel has demonstrated that it is only willing to participate in a friendship with the West that is one-sided; where they reap the benefits of lucrative weapons deals and endless political support while giving no concessions or compromise in return. Outwardly showing resentment to the hand that feeds it when something as simple as a ceasefire is asked for so that the humanitarian crisis on the ground can be properly dealt with.

If we are to look at this in a completely pragmatic sense in regards to foreign policy, we gain nothing from continuing to unconditionally support a historically hostile entity, and we lose nothing if we are to cut these imaginary ties and treat them as we treat any other nation.

There’s an old saying, “With friends like these, who needs enemies?”.

Thankfully, especially amongst younger voters – both liberal and conservative – many are already starting to reevaluate that unquestioning love for a foreign nation that has a long and violent history towards its current allies.

Post Views: 53 -

Technology Is Synonymous With Civilisation

I am declaring a fatwa on anti-tech and anti-civilisational attitudes. In truth, there is no real distinction between the two positions: technology is synonymous with civilisation.

What made the Romans an empire and the Gauls a disorganised mass of tribals, united only by their reactionary fear of the march of civilisation at their doorstep, was technology. Where the Romans had minted currency, aqueducts, and concrete so effective we marvel on how to recreate it, the Gauls fought amongst one another about land they never developed beyond basic tribal living. They stayed small, separated, and never innovated, even with a whole world of innovation at their doorstep to copy.

There is always a temptation to look towards smaller-scale living, see its virtues, and argue that we can recreate the smaller-scale living within the larger scale societies we inhabit. This is as naïve as believing that one could retain all the heartfelt personalisation of a hand-written letter, and have it delivered as fast as a text message. The scale is the advantage. The speed is the advantage. The efficiency of new modes of organisation is the advantage.

Smaller scale living in the era of technology necessarily must go the way of the hand-written letter in the era of text messaging: something reserved for special occasions, and made all the more meaningful for it.

However, no-one would take seriously someone who tries to argue that written correspondence is a valid alternative to digital communication. Equally, there is no reason to take seriously someone who considers smaller-scale settlements a viable alternative to big cities.

Inevitably, there will be those who mistake this as going along with the modern trend of GDP maximalism, but the situation in modern Britain could not be closer to the opposite. There is only one place generating wealth currently: the South-East. Everywhere else in the country is a net negative to Britain’s economic prosperity. Devolution, levelling up, and ‘empowering local communities’ has been akin to Rome handing power over to the tribals to decide how to run the Republic: it has empowered tribal thinking over civilisational thinking.

The consequence of this has not been to return to smaller-scale ways of life, but instead to rest on the laurels of Britain’s last civilisational thinkers: the Victorians.

Go and visit Hammersmith, and see the bridge built by Joseph Bazalgette. It has been boarded up for four years, and the local council spends its time bickering with the central government over whose responsibility it is to fix the bridge for cars to cross it. This is, of course, not a pressing issue in London’s affairs, as the Vercingetorix of the tribals, Sadiq Khan, is hard at work making sure cars can’t go anywhere in London, let alone across a bridge.

Bazalgette, in contrast to Khan, is one of the few people keeping London running today. Alongside Hammersmith Bridge, Bazalgette designed the sewage system of London. Much of the brickward is marked with his initials, and he produced thousands of papers going over each junction, and pipe.

Bazalgette reportedly doubled the pipes diameters remarking “we are only going to do this once, and there is always the possibility of the unforeseen”. This decision prevented the sewers from overflowing in 1960.

Bazalgette’s genius saved countless lives from cholera, disease, and the general third-world condition of living among open excrement. There is no hope today of a Bazalgette. His plans to change the very structure of the Thames would be Illegal and Unworkable to those with power, and the headlines proposing such a feat (that ancient civilisations achieved) would be met with one million image macros declaring it a “manmade horror beyond their comprehension.”

This fundamentally is the issue: growth, positive development, and a future worth living in is simply outside the scope of their narrow comprehension.

This train of thought, having gone unopposed for too long, has even found its way into the minds of people who typically have thorough, coherent, and well-thought-out views. In speaking to one friend, they referred to the current ruling classes of this country as “tech-obsessed”.

Where is the tech-obsession in this country? Is it found in the current government buying 3000 GPUs for AI, which is less than some hedge funds have to calculate their potential stocks? Or is it found in the opposition, who believe we don’t need people learning to code because “AI will do it”?

The whole political establishment is anti-tech, whether crushing independent forums and communities via the Online Harms Bill, to our supposed commitment to be a ‘world leader in AI regulation’ – effectively declaring ourselves to be the worlds schoolmarm, nagging away as the US, China, and the rest of the world get to play with the good toys.

Cummings relays multiple horror stories about the tech in No. 10. Listening to COVID figures down the phone, getting more figures on scraps of paper, using the calculator on his iPhone and writing them on a Whiteboard. Fretting over provincial procurement rules over a paltry 500k to get real-time data on a developing pandemic. He may well have been the only person in recent years serious about technology.

The Brexit campaign was won by bringing in scientists, physicists, and mathematicians, and leveraging their numeracy (listen to this to get an idea of what went on) with the latest technology to campaign to people in a way that had not been done before. Technology, science, and innovation gave us Brexit because it allowed people to be organised on a scale and in ways they never were before. It was only through a novel use of statistics, mathematical models, and Facebook advertising that the campaign reached so many people. The establishment lost on Brexit because they did not embrace new modes of thinking and new technologies. They settled for basic polling of 1-10 thousand people and rudimentary mathematics.

Meanwhile the Brexit campaign reached thousands upon thousands, and applied complex Bayesian statistics to get accurate insights into the electorate. It is those who innovate, evolve, and grow that shape the future. There is no going back to small-scale living. Scale is the advantage. Speed is the advantage. And once it exists, it devours the smaller modes of organisation around it, even smaller modes of organisation have the whole political establishment behind it.

When Cummings got what he wanted injected into the political establishment – a data science team in No. 10 – they were excised like a virus from the body the moment a new PM was installed. Tech has no friends in the political establishment, the speed, scale, and efficiency of the thing is anathema to a system which relies on slow-moving processes to keep a narrow group of incompetents in power for as long as possible. The fierce competition inherent to technology is the complete opposite of the ‘Rolls-Royce civil service’ which simply recycles bad staff around so they don’t bother too many people for too long.

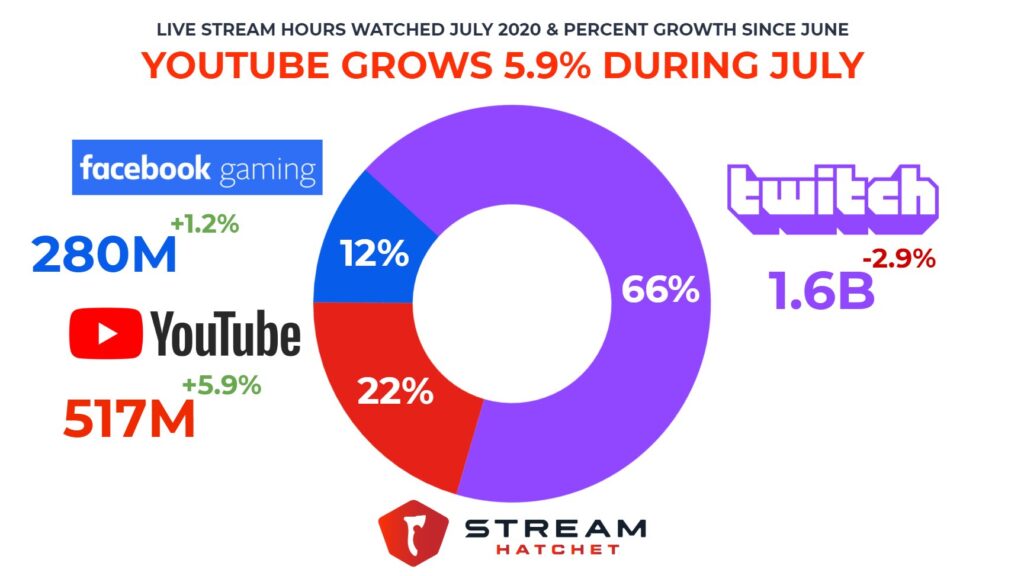

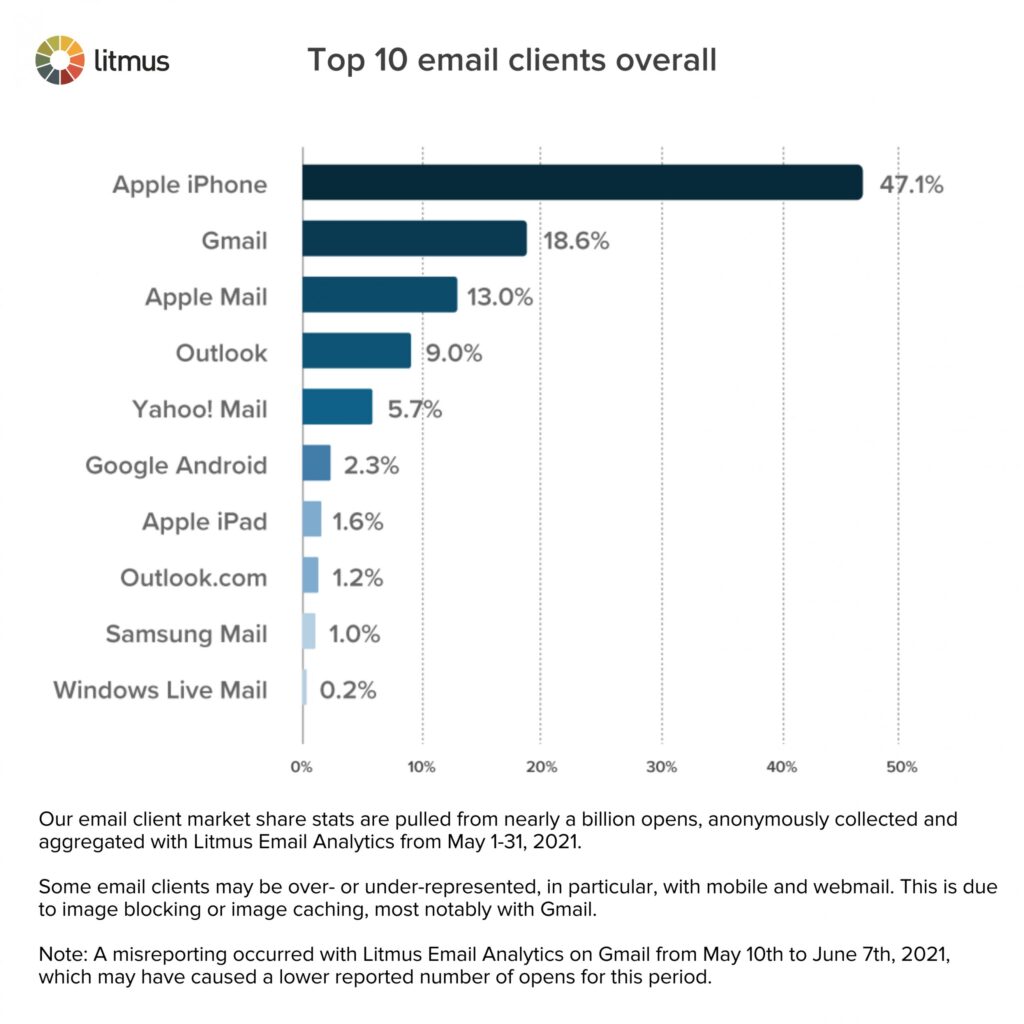

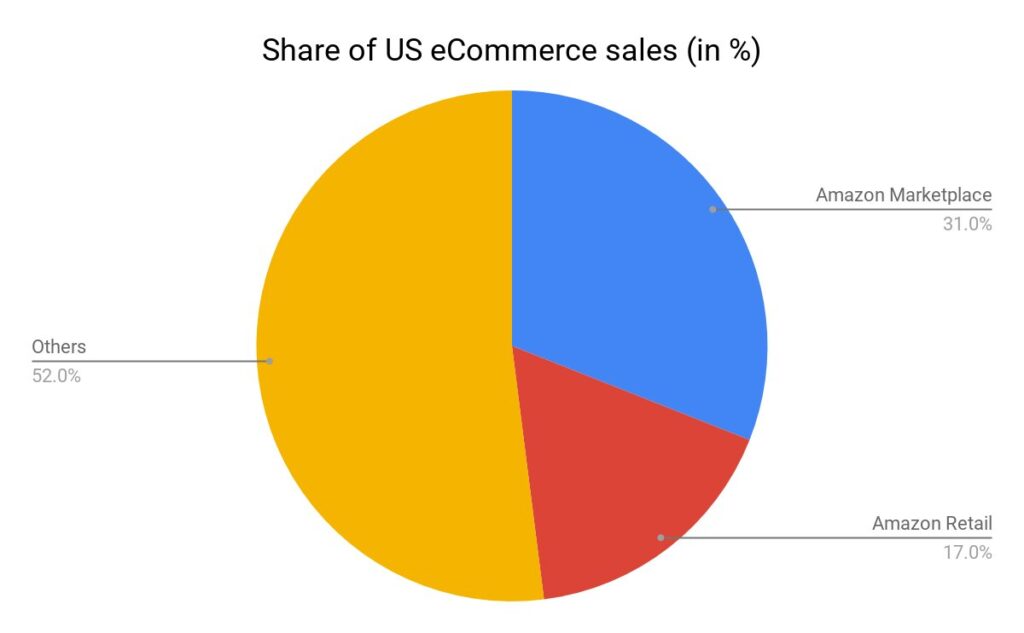

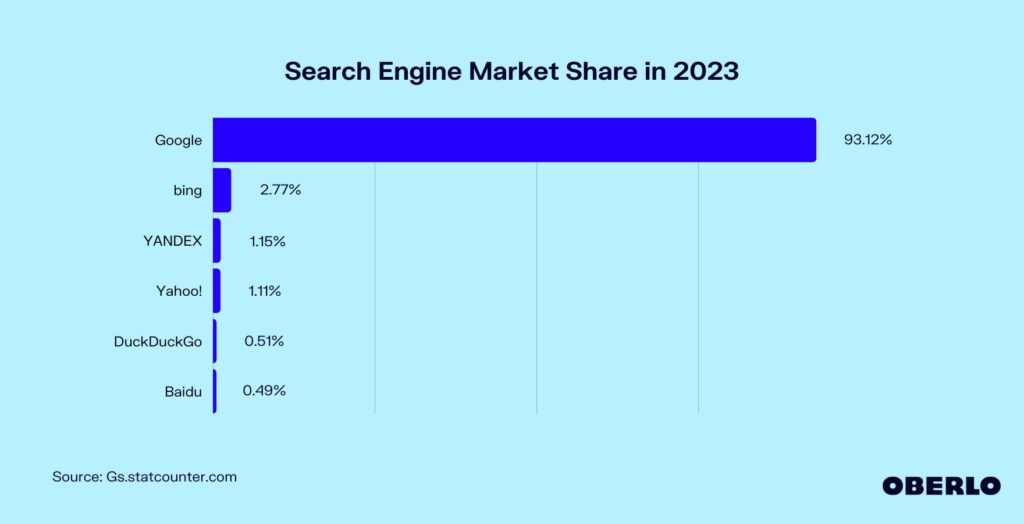

By contrast, in tech, second best is close to last. When you run the most popular service, you get the data from running that service. This allows you to make a better service, outcompete others, which gets you more users, which gets you more data, and it all snowballs from there. Google holds 93.12% of the search engine market share. Amazon owns 48% of eCommerce sales. The iPhone is the most popular email client, at 47.13%. Twitch makes up 66% of all hours of video content watched. Google Chrome makes up 70% of web traffic. There next nearest competitor, Firefox (a measly 8.42%,) is only alive because Google gave them 0.5b to stick around. Each one of these companies is 2-40 times bigger than its next nearest competitor. Just as with civilisation, there is no half-arseing technology. It is build or die.

Nevertheless, there have been many attempts to half-ass technology and civilisation. When cities began to develop, and it became clear they were going to be the future powerhouses of modern economies, theorists attempted to create a ‘city of towns’ model.

Attempting to retain the virtues of small town and community living in a mass-scale settlement, they argued for a model of cities that could be made up of a collection of small towns. Inevitably, this failed.

The simple reason is that the utility of cities is scale. It is the access to the large labour pools that attracts businesses. If cities were to become collections of towns, there would be no functional difference in setting up a business in a city or a town, except perhaps the increased ground rent. The scale is the advantage.

This has been borne out mathematically. When things reach a certain scale, when they become networks of networks (the very thing you’re using, the internet, is one such example) they tend towards a winner-takes-all distribution.

Bowing out of the technological race to engage in some Luddite conquest of modernity, or to exact some grudge against the Enlightenment, is signalling to the world we have no interest in carving out our stake in the future. Any nation serious about competing in the modern world needs to understand the unique problems and advantages of scale, and address them.

Nowhere is this more strongly seen than in Amazon, arguably a company that deals with scale like no other. The sheer scale of co-ordination at a company like Amazon requires novel solutions which make Amazon competitive in a way other companies are not.

For example, Amazon currently owns the market on cloud services (one of the few places where a competitor is near the top, Amazon: 32%, Azure: 23%). Amazon provides data storage services in the cloud with its S3 service. Typically, data storage services have to handle peak times, when the majority of the users are online, or when a particularly onerous service dumps its data. However, Amazon services so many people – its peak demand is broadly flat. This allows Amazon to design its service around balancing a reasonably consistent load, and not handling peaks/troughs. The scale is the advantage.

Amazon warehouses do not have designated storage space, nor do they even have designated boxes for items. Everything is delivered and everything is distributed into boxes broadly at random, and tagged by machines so the machines know where to find it.

One would think this is a terrible way to organise a warehouse. You only know where things are when you go to look for them, how could this possibly be advantageous? The advantage is in the scale, size, and randomness of the whole affair. If things are stored on designated shelves, when those shelves are empty the space is wasted. If someone wants something from one designated shelf on one side of the warehouse, and something from another side of the factory, you waste time going from one side to the other. With randomness, you are more likely to have a desired item close by, as long as you know where that is, and with technology you do. Again, the scale is the advantage.

The chaos and incoherence of modern life, is not a bug but a feature. Just as the death of feudalism called humans to think beyond their glebe, Lord, and locality, the death of legacy media and old forms of communication call humans to think beyond the 9-5, elected representative, and favourite Marvel movie.

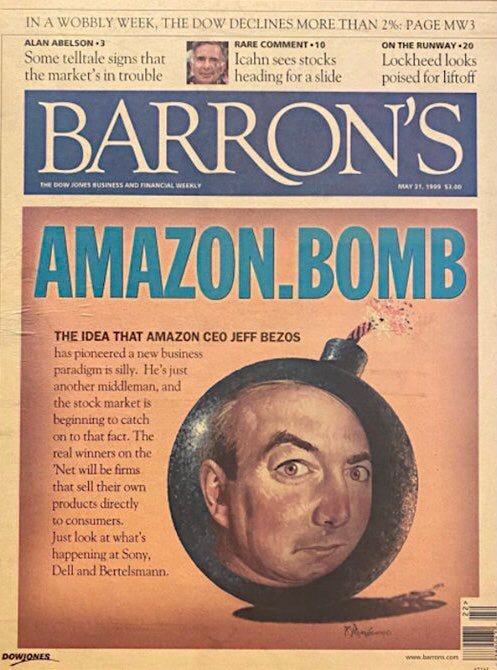

In 1999, one year after Amazon began selling music and videos, and two years after going public – Barron’s, a reputable financial magazine created by Dow Jones & Company posted the following cover:

Remember, Barron’s is published by Dow Jones, the same people who run stock indices. If anyone is open to new markets, it’s them. Even they were outmanoeuvred by new technologies because they failed to understand what technophobes always do: scale is the advantage. People will not want to buy from 5 different retailers because they want to buy everything all at once.

Whereas Barron’s could be forgiven for not understanding a new, emerging market such as eCommerce, there should be no sympathy for those who spend most of their lives online decrying growth. Especially as they occupy a place on the largest public square to ever occur in human existence.

Despite claiming they want a small-scale existence, their revealed preference is the same as ours: scale, growth, and the convenience it provides. When faced with a choice between civilisation in the form of technology, and leaving Twitter a lifestyle closer to that of the past, even technology’s biggest enemies choose civilisation.

Post Views: 678