latest

Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better

Since Brexit, an embittered, drawn-out separation procedure which homogenised the UK’s political news for almost half a decade, political commentators have routinely surmised the future of the UK-EU relationship.

Whatever differences may exist in the specifics of their predictions, many operate under the pervasive assumption that the relationship is a work in progress – it doesn’t quite know what it is yet, it needs time to root itself into something tangible, which thereafter can be analysed at a deeper level.

Unfortunately for professional pontificators, the essence of the post-Brexit UK-EU relationship has already materialised: “anything you can do, I can do better.”

One might argue that every international relationship is like this. Even where this concord and sainted ‘co-operation’, the vying interests of states lurks beneath the surface.

Whilst it’s true that competition is an indelible component of politics, it’s worth noting that just because states can act in their own interests doesn’t mean they will. Now more than ever, the course of politics is dictated by PR, rather than policy.

As such, when policy considerations arise, states are prone to pursue goals which aren’t necessarily in their interests but provide a presentational veneer of ‘superiority’ when compared to rivals.

“Shot yourself in the foot, eh? What’s that? With a flintlock pistol? Pfft. Amateur.”

*Proceeds to aim cartoonishly large blunderbuss at own foot*

The UK’s ‘divorce’ from the EU was officialised over 3 years, yet both are desperate to ensure the other is perceived, well-in view of family, friends, and random strangers, as the cause for the nasty, bitter, and very well-publicised breakdown of relations.

In response to the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act, the world’s first AI regulatory framework, Paul Graham’s brief, but accurate, outline of the EU’s relationship with technology regained online attention:

America: Let's have a party. I'll bring the software!

— Paul Graham (@paulg) February 23, 2020

China: I'll bring the hardware!

EU: I'll bring the regulation!

America, China:

Following the EU’s announcement, the UK government announced their intention to one-up them. Prime Minister Sunak pitched Britain as the future home for AI regulation.

On the surface, it looks like the UK is one-upping the EU, beating them at their own game, doing EU tech policy more effectively than the EU themselves.

This wouldn’t be bad thing if the EU didn’t suck at tech, something even its most ardent supporters have admitted. It’s not a coincidence that none of the top 10 tech global companies are from the EU, or that every tech start-up leaves for (or gets bought-up by) the United States or China.

In America, you are told to “get out there and do it!” In China, you are told to “get out there and do it, or else.” In Europe, you are told to “sit tight as we process your application.”

Despite their differences, whether ‘entrepreneurial’ or ‘statist’ in their methods, both America and China have a far more action-oriented culture than Europe, which is inclined towards deliberation.

Given this, the UK is well-poised to become technophilic outpost in a seemingly technophobic region of the world – the beginnings of a positive post-Brexit vision.

The Prime Minister seems to, at the very least, loosely understand this fact, as the recent tweet gaffe would suggest, but continues to push the aspiration of turning Britain into Europe’s biggest bureaucratic wart.

However, this “Anything you can do…” attitude transcends the realm of tech policy, extending to other major areas, such as the environment and energy security.

Back in 2021, UK Environment Act came into force. Described by the government as the most ambitious environmental programme of any country on earth, the bill includes, amongst other loosely connected environmental commitments, new rules to stop the import of wood to the UK from areas of illegally deforested land.

Initially implemented as an expression of new powers acquired through Brexit, hoping to upstage the EU by implementing comparatively stricter environmental regulations, the EU have since ‘one-upped’ the Brits in pursuit of going green.

In December 2022, the European Commission approved a “first-of-its-kind” deforestation-free law: European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR).

EUDR is one of several measures by the EU to tackle biodiversity loss driven by deforestation and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, aiming to achieve net-zero by 2050.

Set to be implemented in December 2024, the EUDR prohibits lumber and pulp companies ensure from importing any material which has contributed to deforestation after December 2020.

Additionally, companies must know the origin of their products, ensure their products are produced legally in their country of origin, and obtain precise geolocation data for all the products they place on the EU market.

If companies fail to comply with the incoming regulations, they will not be allowed to sell their products on the EU market. Expectedly, companies with business practices in violation of the EUDR will face criminal charges, including non-compliance penalties of up to 4% of their EU turnover.

Putting aside snide comments about European pedanticism (isn’t selling lumber definitive proof of deforestation, what more proof do you need?!), this new regulatory framework is significant for two major reasons.

Firstly, the EU accounts for one-sixth of the global lumber trade and over $4 billion in tropical timber-related imports alone, contributing to the highest import value in a decade.

Whilst wood imports to the EU from Russia have declined, largely due to incrementally impose restrictions dating back to the 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia was still Europe’s main provider of wood, exporting (alongside Belarus and Ukraine) $6.71 billion’s worth of wood (including furniture) to the EU in 2022.

To provide such a strict and through regulatory framework for a market as large and as unprepared as the timber trade is ambitious, to say the least.

New data from the Zoological Society of London’s Sustainability Policy Transparency Toolkit (SPOTT) assessment shows only 13.3% of lumber and pulp companies are publicly monitoring deforestation within their own operations, and only 4.3% are monitoring their supplier’s operations.

Only 6.4% of the 90 companies surveyed by SPOTT are currently able to trace 100% of their supply to the location of harvest. Additionally, only 21.3% of companies report the processes they use to ensure suppliers comply with their legal requirements.

Secondly, during the winter of last year, firewood prices spiked, warehouses were placed under immense pressure, and crime (especially illegal logging) flourished, both in the EU and the UK.

In August 2022, firewood sales in the UK surged by a fifth, around which time wood pellets nearly doubled in France, Bulgaria, Poland, and several other EU counties, with practically all of Europe scrambling for firewood, drowning out the protestation of environmentalists.

Whilst this was certainly caused by Europe’s ‘green’ policies, such as the closure of Germany’s last operating nuclear power stations, and the embargos on Russian gas, leading people to source alternative sources of fuel, the EU’s less-than-publicised import ban of Russian wood and pellets in the month prior certainly did the trick.

Given that building up a reliable, long-term stock of relatively clean energy is politically untouchable, it’s safe to assume things will get worse, if not much better; that goes for both the Europe-wide energy crisis and the UK-EU relationship.

Indeed, “Anything you can do…” has trickled down into the media class. Several commentators have remarked that as Europe lurches rightward, the UK has remained a bastion of liberalism, on course to elect the centre-left Remainer-led party by a landslide.

This flies in the face of several important facts, such as Britain’s electoral system which does not reward upstart or fringe parties in the same way many EU countries do, or that Britons (when asked) generally display conservative views on immigration (and have done so for over 30-odd years), having arguably led the ongoing ‘right-wing populist revolt, etc, etc.’ with UKIP, Brexit, and the 2019 General Election, or that Christian, social, and liberal democratic still have a lot of electoral influence across Europe.

If Britain is a bastion of liberal/social democracy, and Europe is becoming a post-fascist conservative bloc, where does that leave their droopy-eyed fascination with ‘Bregret‘?

The rather boring reality is that the politics of the UK’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU will be non-existent. Policy agendas and goals remain aligned on a fundamental level, with the only ‘political’ tension constituting a war of nerves – in short, not especially political at all.

If it was political, there would be room to instate the reform our state so desperately requires.

Her Penis is Boring

Oh good. You get a package and creatively wrap it. Who doesn’t love a Dutch surprise?

It’s all very predictable. As soon as you see the headline, you know what’s going to happen.

A great big chunk of the normie right, and even the more based/red-pilled/dissident/whatever right, have reacted like this. What do you reckon, do you recognise the below?

“Outrageous! *What do they mean HER penis*? If the left did this eh meh meh hypocrisy blah! Harumph, most unorthodox! If a man did this! We’ve fallen so far, the future of our country, something something the Queen. Splutters champagne, monocle falls out, but with Victorian era mutton chops.”

OK, the last bit might be a little unfair. You get the point though, don’t you?

Is this really some great new surprise or at all shocking? No! It’s been done to death and now they’re acting out with increasingly more extreme things to get the same level of reaction, attention, etc. to try and keep any buzz or excitement going in their latest fad.

Now they’re getting their ‘tits’ out at the White House. What’s next? Synchronised helicopters at the Cenotaph this November while the King stands to attention? This is all so dumb and transparent. Why are you reacting as if it’s anything other than boring?

The ‘right’ is the most promising place anything new or interesting is likely to come from. It’s on the outside. It’s not establishment normalcy, curated and factory-made orthodoxy. When it reacts in such predictable ways to such obvious dreariness, it’s really letting itself down. Don’t let your enemies feel like insurgents when they’re cradled by the status quo. Let them jump the shark.

Reacting is a diversion of your energy from more important things. Minority issues cut both ways. Sure, ‘most people’ (do majorities matter, or does winning matter?) might agree with you, and it might even count for something, but how high on their list of priorities is it? Yes, take the low hanging fruit, or perhaps this is an issue which also largely takes care of itself if enough (of the relevant) people are on your side.

Yes, this may have played a role in bringing down Nicola Sturgeon, but how significant was that? What role did money problems play? And the SNP are still there, with Labour next best positioned to take over. Nothing big or culturally or politically is really that different in Scotland. For the whole UK what still stands? The economy, immigration, house prices, tax rates, NHS standards, take your pick of any issue which needs more work.

For now, let the TERFs and trans people have at it. It’s not like the TERFs are your friends. Why give any quarter to a slightly different strain of the progressive problem?

And on a totally basic level, isn’t it just stupid to bother fighting ‘to prove’ (to who?) that men are men and women are women? This is really just a playground case where someone calls you a name, and you either call them one back or ignore it. You don’t waste energy trying to persuade your accuser that you are not whatever they called you.

Just like the playground, they don’t really believe in ‘her penis’ anyway. It’s a shit test, ab initiation rite, an in-group/out-group signifier. It’s like molesting a pig to get into the Bullingdon Club or whatever. Well, that’s the Machiavellian side. A lot of these people are just useful idiots, aren’t party insiders, don’t have a clue, and really have the same energy as the ones who have the power of God and anime on their side. Either way, don’t bother. It’s stupid.

Are we really wasting energy on something as basic as this rather than just going “no” and carrying on with something real, something that might need more real fighting over?

Don’t waste the energy. They’re better prepared for it and you’re just feeding the trolls, following the paths they’ve laid out for you.

When you react in the ways they expect:

- They have their own set ways to react, and the game keeps going,

- They’re ready and waiting, don’t do what they expect and wrongfoot them,

- You keep their fad alive, and…

- It makes you look like you’re just doing the same old thing you’ve done since 2016 or whenever.

The more you disengage, the more they’ll look for a different game, or otherwise chase the high by pushing the absolute limits of their ideological/aesthetic paradigm. Eventually they run out of things to do, or it breaks, or people will get so totally disgusted by it that it provokes a real reaction. Interpret ‘reaction’ as you will.

Your instinct to react now is understandable, but it’s not useful. Yes, you’re right, progressives do get away with all sorts of things. On one level it’s because they have power to enforce what they want, defend their people, and you don’t. On another it’s because they have the kinds of religious fervent nutters who will throw bricks through people’s windows, glue themselves to roads, throw Molotov cocktails, etc. and your side doesn’t.

Well, OK, then you have to work with the people you’ve got. It means treating this for what it is. Boring!

Britain Is No Longer a Land of Opportunity

A recent viral tweet showed two doctors leaving a hospital. They’ve surrendered their licenses to practice medicine in Britain and are instead heading off to work in Australia. It’s not unusual- the majority of foreign doctors in Australia are Brits. The problem lies in the fact that young, educated doctors do not see themselves thriving in Britain. Our pay and conditions are not good enough for them.

Are you annoyed at them for being educated through taxpayer funding before going abroad? Many are. Are you understanding as to why? So are others.

Whilst this particular tale does come down to problems with the NHS, it’s also an example of what is wrong with Britain at the moment. People, especially younger ones, haven’t got the opportunities that they should have. There is no aspiration. There is a lot to reach for and not a lot to grab.

What has happened?

Wages and Salaries and Income, Oh My!

A recent investigation by a think tank has revealed that 15 years of economic stagnation has seen Brits losing £11K a year in wages. Let’s put this into perspective. Poland and Eastern Europe are seeing a rise in GDP- Poland is projected to be richer than us in 12 years should our economic growth remain the same. The lowest earners in Britain have a 20% weaker standard of living than Slovenians in the same situation.

That’s a lot of numbers to say that wages and salaries aren’t that great.

By historical standards, the tax burden in the U.K. is very high. COVID saw the government pumping money into furlough schemes and healthcare. As the population ages, there is a further need for health and social care support. This results in taxes eating into a larger amount of our income. In fact, more adults than ever are paying 40% or above in taxation. It’s a significant number. One might argue that this does generally only apply to the rich and thus 40% is not a high amount for them, but is that a fair number?

With inflation increasing costs and house prices rising (more on that later), a decent standard of living is beyond the reach of many. This is certainly true for young people. With wages and salaries falling in real time, we do not have the same opportunities as our parents and grandparents. Families used to be able to live comfortably on one wage, something that is near impossible. Our taxes are going on healthcare for an aging population.

Do we want old people to die? Of course not. We just do not have the benefits that they did. Our income is going towards their comfort. Pensioners have higher incomes than working age people.

Compared to the United States, Brits have lower wages. One can argue that it is down to several things- more paid holidays and taxpayer funded healthcare. That is true, and many Brits will proudly compare the NHS to the American healthcare system. That is fine, but when the NHS is in constant crisis, we don’t seem to be getting our money’s worth. The average American salary is 12K higher than the average Brit’s. The typical US household is 64% richer. Whilst places like New York and San Francisco have extortionate house prices, it’s generally cheaper across the US.

Which brings us onto housing.

A House is Not a Home

Houses are expensive- they are at about 8.8% higher than the average income. This is compared to 4% in the 1990s. That itself is an immediate roadblock to many. Considering how salaries have stagnated, as discussed in the previous section, it’s only obvious that homeowning is a dream as opposed to reality.

Rent is not exactly affordable either. In London, the average renter spends more than half of their income on rent. Stories of people queuing for days and landlords taking much higher offers are commonplace.

House building itself is not cheap- the price of bricks have absolutely rocketed over recent years. Factors include a shortage of housing stock and increased utilities. House building itself is also not easy.

NIMBYs have an aneurysm at the thought of an abandoned bingo hall being turned into housing. MPs in leafy suburbs push against any new developments, lest their wealthy parishioners vote for somebody else. Theresa Villiers, whose constituency sees homes average twice the U.K. mean price, led Tory MPs in an attempt to prevent house building targets.

We get the older folks telling us that we just need to work harder. It’s easy for them to say, considering a higher proportion of our income is needed to just get a damn deposit. If we’re paying more and more of our income on rent, how can we save?

Playing Mummy and Daddy

The ambition to become a parent is something many hold, but it is again an ambition that is unattainable. Well, the actual having the child part is easy, but it’s what comes after that makes it tough.

Firstly, we cannot get our own homes. Few want to raise their children in one bed flats with no gardens. To plan for a child is to likely plan a move.

Secondly, childcare is very expensive. Years and years ago, men went to work and women stayed home with the children as a rule. Of course, that did not apply to the working class, but it was a workable system. Nowadays, you both have to work. Few can survive on a single income from either parent. Grandparents are often working themselves or simply don’t/can’t provide babysitting duties. This leaves only one choice- professional childcare. The average cost of childcare during the summer holidays is £943. Some parents pay more than half of their wages on childcare.

Thirdly, as has been said, everything is more expensive these days. One only has to look at something basic like school uniforms- some spend over £300 per child. It’s not cheap to look after adults, let alone children.

The Golden Years

The focus of this piece is generally on young and working age people, but the cost of social care is pretty bad. With the costs of home and residential health care increasing constantly, it means that many will lose their hard earned savings. Houses must be sold and pensions given up. It is unfair that we must work all of our lives but then leave nothing for our children if we wish. Whilst residential homes are alien concepts to many in cultures where they look after the elderly, many factors in the U.K. mean that it is more common.

On balance, pensioners are better off than the young, but what about those who need care? It may be bad now, but what about when we ourselves are old? We will likely still be working at 70 and having to pay more for our care.

The Party of Aspiration and 13 Years of Power

The Conservatives have always called themselves the party of aspiration. They’ve been in power for 13 years, eight of which were without a coalition party. The Tories won a stunning majority in 2019 under Boris Johnson. They’ve had the opportunity to do something about this but haven’t. It’s amazing that they wonder why young people don’t vote for them anymore.

Let’s not pretend Labour and the Lib Dems are any better either. The Lib Dems won the historical Tory seat of Chesham and Amersham partially by appealing to those worried about new housing. Labour’s plans aren’t particularly inspiring.

We cannot dream in Britain anymore. The land of hard work and fair reward is no more. We must simply sit by as our wages stagnate, houses get too expensive and the opportunity for family passes us by. Our doctors head to Australia for better pay and better conditions. Countries that would see immigrants come to us for a better life are seeing their own economies grow.

People shouldn’t be living with roommates in their 30s when what they want is a family. We deserve to work hard to secure a good future. We don’t deserve for our income to go on poor services and for our savings to go on residential care.

The Tories have had thirteen years to sort it out. Labour and the Lib Dems have had chances to put their plans across. Our politicians care more about talking points and pretty photo ops than improving our lives.

Let us have ambition. Let us seek opportunities. Let Britain be a land of opportunity once again.

The Chinese Revolution – Good Thing, Bad Thing?

This is an extract from the transcript of The Chinese Revolution – Good Thing, Bad Thing? (1949 – Present). Do. The. Reading. and subscribe to Flappr’s YouTube channel!

“Tradition is like a chain that both constrains us and guides us. Of course, we may, especially in our younger years, strain and struggle against this chain. We may perceive faults or flaws, and believe ourselves or our generation to be uniquely perspicacious enough to radically improve upon what our ancestors have made – perhaps even to break the chain entirely and start afresh.

Yet every link in our chain of tradition was once a radical idea too. Everything that today’s conservatives vigorously defend was once argued passionately by reformers of past ages. What is tradition anyway if not a compilation of the best and most proven radical ideas of the past? The unexpectedly beneficial precipitate or residue retrieved after thousands upon thousands of mostly useless and wasteful progressive experimentation.

To be a conservative, therefore, to stick to tradition, is to be almost always right about everything almost all the time – but not quite all the time, and that is the tricky part. How can we improve society, how can we devise better governments, better customs, better habits, better beliefs without breaking the good we have inherited? How can we identify and replace the weaker links in our chain of tradition without totally severing our connection to the past?

I believe we must begin from a place of gratitude. We must hold in our minds a recognition that life can be, and has been, far worse. We must realize there are hard limits to the world, as revealed by science, and unchangeable aspects of human nature, as revealed by history, religion, philosophy, and literature. And these two facts in combination create permanent unsolvable problems for mankind, which we can only evade or mitigate through those traditions we once found so constraining.

To paraphrase the great G.K. Chesterton: “Before you tear down a fence, understand why it was put up in the first place.” I cannot fault a single person for wishing to make a better world for themselves and their children, but I can admonish some persons for being so ungrateful and ignorant, they mistake tradition itself as the cause of every evil under the sun. Small wonder then that their hairbrained alternatives routinely overlook those aspects of society without which it cannot function or perpetuate itself into the future.

And there are other things tied up in tradition besides moral guidance or the management of collective affairs. Tradition also involves how we delve into the mysteries of the universe; how we elevate the basic needs of food, shelter, and clothing into artforms unto themselves; how we represent truth and beauty and locate ourselves within the vast swirling cosmos beyond our all too brief and narrow experience.

It is miraculous that we have come as far as we have. And at any given time, we can throw that all away, through profound ingratitude and foolish innovations. A healthy respect for tradition opens the door to true wisdom. A lack of respect leads only to novelty worship and malign sophistry.

Now, not every tradition is equal, and not everything in a given tradition is worth preserving, but like the Chinese who show such great deference to the wisdom of their ancestors, I wish more in the West would admire or even learn about their own.

Like the Chinese, we are the legatees of a glorious tradition – a tradition that encompasses the poetry of Homer, the curiosity of Eratosthenes, the integrity of Cato, the courage of Saint Boniface, the vision of Michelangelo, the mirth of Mozart, the insights of Descartes, Hume, and Kant, the wit of Voltaire, the ingenuity of Watt, the moral urgency of Lincoln and Douglas.

These and many more are responsible for the unique tradition into which we have been born. And it is this tradition, and no other, which has produced those foundational ideas we all too often take for granted, or assume are the defaults around the world. I am speaking here of the freedom of expression, of inquiry, of conscience. I am speaking of the rule of law, and equality under the law. I am speaking of inalienable rights, of trial by jury, of respect for women, of constitutional order and democratic procedure. I am speaking of evidence based reasoning and religious tolerance.

Now those are all things I wouldn’t give up for all the tea in China. You can have Karl Marx. We’ll give you him. But these are ours. They are the precious gems of our magnificent Western tradition, and if we do nothing else worthwhile in our lives, we can at least safeguard these things from contamination, or annihilation, by those who would thoughtlessly squander their inheritance.”

Technology Is Synonymous With Civilisation

I am declaring a fatwa on anti-tech and anti-civilisational attitudes. In truth, there is no real distinction between the two positions: technology is synonymous with civilisation.

What made the Romans an empire and the Gauls a disorganised mass of tribals, united only by their reactionary fear of the march of civilisation at their doorstep, was technology. Where the Romans had minted currency, aqueducts, and concrete so effective we marvel on how to recreate it, the Gauls fought amongst one another about land they never developed beyond basic tribal living. They stayed small, separated, and never innovated, even with a whole world of innovation at their doorstep to copy.

There is always a temptation to look towards smaller-scale living, see its virtues, and argue that we can recreate the smaller-scale living within the larger scale societies we inhabit. This is as naïve as believing that one could retain all the heartfelt personalisation of a hand-written letter, and have it delivered as fast as a text message. The scale is the advantage. The speed is the advantage. The efficiency of new modes of organisation is the advantage.

Smaller scale living in the era of technology necessarily must go the way of the hand-written letter in the era of text messaging: something reserved for special occasions, and made all the more meaningful for it.

However, no-one would take seriously someone who tries to argue that written correspondence is a valid alternative to digital communication. Equally, there is no reason to take seriously someone who considers smaller-scale settlements a viable alternative to big cities.

Inevitably, there will be those who mistake this as going along with the modern trend of GDP maximalism, but the situation in modern Britain could not be closer to the opposite. There is only one place generating wealth currently: the South-East. Everywhere else in the country is a net negative to Britain’s economic prosperity. Devolution, levelling up, and ‘empowering local communities’ has been akin to Rome handing power over to the tribals to decide how to run the Republic: it has empowered tribal thinking over civilisational thinking.

The consequence of this has not been to return to smaller-scale ways of life, but instead to rest on the laurels of Britain’s last civilisational thinkers: the Victorians.

Go and visit Hammersmith, and see the bridge built by Joseph Bazalgette. It has been boarded up for four years, and the local council spends its time bickering with the central government over whose responsibility it is to fix the bridge for cars to cross it. This is, of course, not a pressing issue in London’s affairs, as the Vercingetorix of the tribals, Sadiq Khan, is hard at work making sure cars can’t go anywhere in London, let alone across a bridge.

Bazalgette, in contrast to Khan, is one of the few people keeping London running today. Alongside Hammersmith Bridge, Bazalgette designed the sewage system of London. Much of the brickward is marked with his initials, and he produced thousands of papers going over each junction, and pipe.

Bazalgette reportedly doubled the pipes diameters remarking “we are only going to do this once, and there is always the possibility of the unforeseen”. This decision prevented the sewers from overflowing in 1960.

Bazalgette’s genius saved countless lives from cholera, disease, and the general third-world condition of living among open excrement. There is no hope today of a Bazalgette. His plans to change the very structure of the Thames would be Illegal and Unworkable to those with power, and the headlines proposing such a feat (that ancient civilisations achieved) would be met with one million image macros declaring it a “manmade horror beyond their comprehension.”

This fundamentally is the issue: growth, positive development, and a future worth living in is simply outside the scope of their narrow comprehension.

This train of thought, having gone unopposed for too long, has even found its way into the minds of people who typically have thorough, coherent, and well-thought-out views. In speaking to one friend, they referred to the current ruling classes of this country as “tech-obsessed”.

Where is the tech-obsession in this country? Is it found in the current government buying 3000 GPUs for AI, which is less than some hedge funds have to calculate their potential stocks? Or is it found in the opposition, who believe we don’t need people learning to code because “AI will do it”?

The whole political establishment is anti-tech, whether crushing independent forums and communities via the Online Harms Bill, to our supposed commitment to be a ‘world leader in AI regulation’ – effectively declaring ourselves to be the worlds schoolmarm, nagging away as the US, China, and the rest of the world get to play with the good toys.

Cummings relays multiple horror stories about the tech in No. 10. Listening to COVID figures down the phone, getting more figures on scraps of paper, using the calculator on his iPhone and writing them on a Whiteboard. Fretting over provincial procurement rules over a paltry 500k to get real-time data on a developing pandemic. He may well have been the only person in recent years serious about technology.

The Brexit campaign was won by bringing in scientists, physicists, and mathematicians, and leveraging their numeracy (listen to this to get an idea of what went on) with the latest technology to campaign to people in a way that had not been done before. Technology, science, and innovation gave us Brexit because it allowed people to be organised on a scale and in ways they never were before. It was only through a novel use of statistics, mathematical models, and Facebook advertising that the campaign reached so many people. The establishment lost on Brexit because they did not embrace new modes of thinking and new technologies. They settled for basic polling of 1-10 thousand people and rudimentary mathematics.

Meanwhile the Brexit campaign reached thousands upon thousands, and applied complex Bayesian statistics to get accurate insights into the electorate. It is those who innovate, evolve, and grow that shape the future. There is no going back to small-scale living. Scale is the advantage. Speed is the advantage. And once it exists, it devours the smaller modes of organisation around it, even smaller modes of organisation have the whole political establishment behind it.

When Cummings got what he wanted injected into the political establishment – a data science team in No. 10 – they were excised like a virus from the body the moment a new PM was installed. Tech has no friends in the political establishment, the speed, scale, and efficiency of the thing is anathema to a system which relies on slow-moving processes to keep a narrow group of incompetents in power for as long as possible. The fierce competition inherent to technology is the complete opposite of the ‘Rolls-Royce civil service’ which simply recycles bad staff around so they don’t bother too many people for too long.

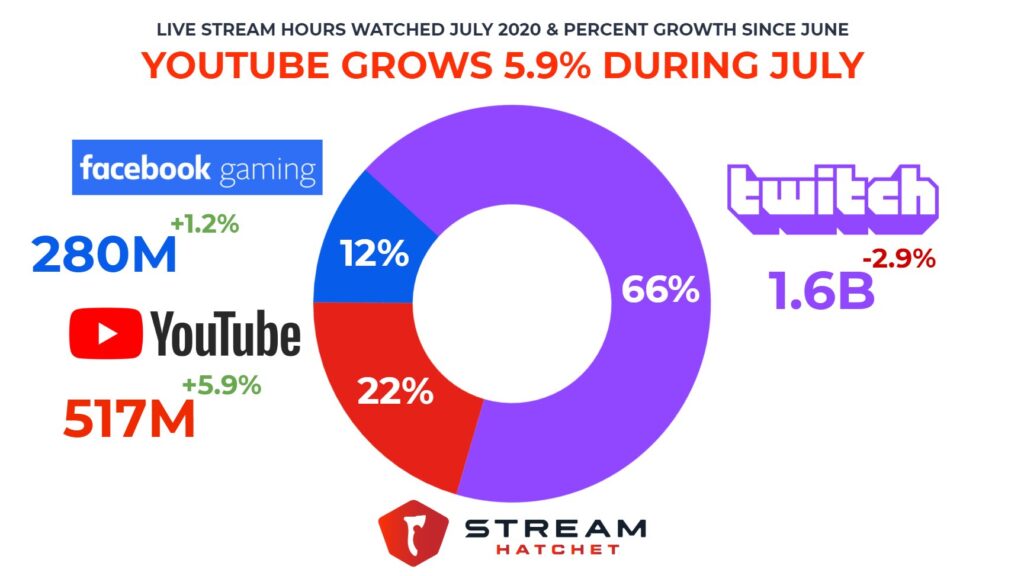

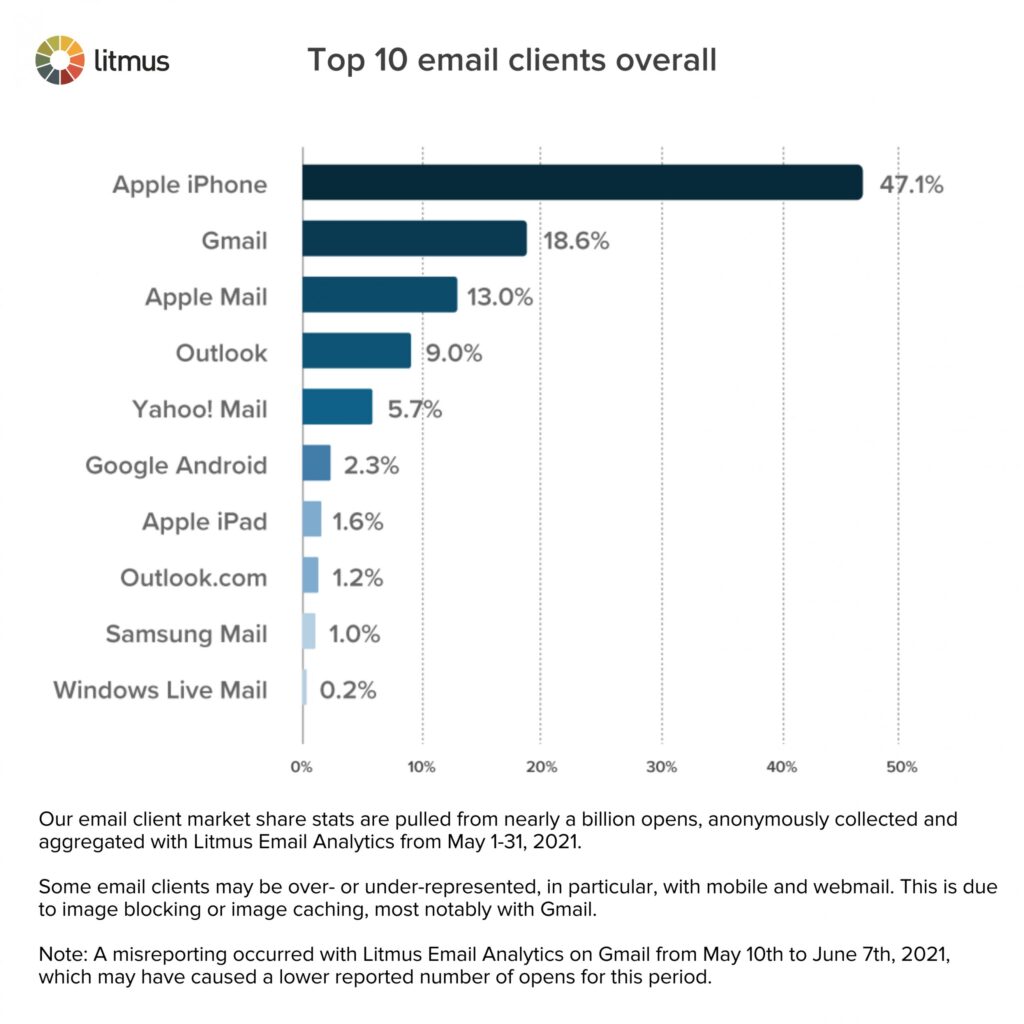

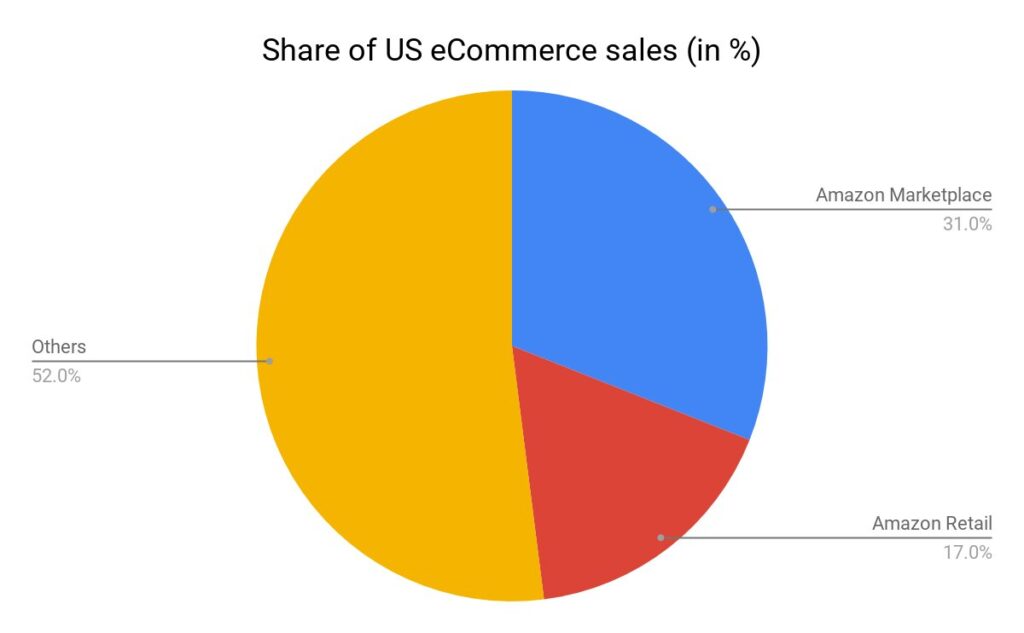

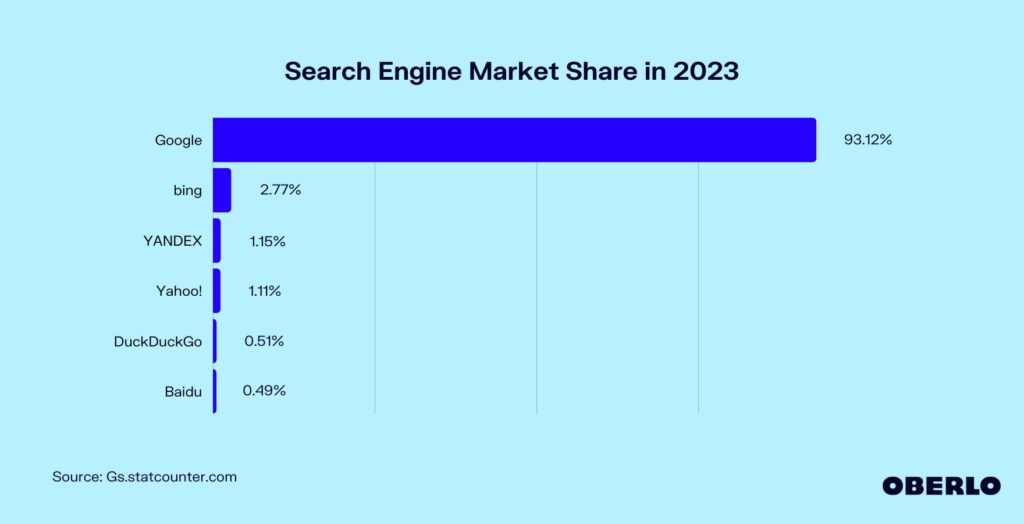

By contrast, in tech, second best is close to last. When you run the most popular service, you get the data from running that service. This allows you to make a better service, outcompete others, which gets you more users, which gets you more data, and it all snowballs from there. Google holds 93.12% of the search engine market share. Amazon owns 48% of eCommerce sales. The iPhone is the most popular email client, at 47.13%. Twitch makes up 66% of all hours of video content watched. Google Chrome makes up 70% of web traffic. There next nearest competitor, Firefox (a measly 8.42%,) is only alive because Google gave them 0.5b to stick around. Each one of these companies is 2-40 times bigger than its next nearest competitor. Just as with civilisation, there is no half-arseing technology. It is build or die.

Nevertheless, there have been many attempts to half-ass technology and civilisation. When cities began to develop, and it became clear they were going to be the future powerhouses of modern economies, theorists attempted to create a ‘city of towns’ model.

Attempting to retain the virtues of small town and community living in a mass-scale settlement, they argued for a model of cities that could be made up of a collection of small towns. Inevitably, this failed.

The simple reason is that the utility of cities is scale. It is the access to the large labour pools that attracts businesses. If cities were to become collections of towns, there would be no functional difference in setting up a business in a city or a town, except perhaps the increased ground rent. The scale is the advantage.

This has been borne out mathematically. When things reach a certain scale, when they become networks of networks (the very thing you’re using, the internet, is one such example) they tend towards a winner-takes-all distribution.

Bowing out of the technological race to engage in some Luddite conquest of modernity, or to exact some grudge against the Enlightenment, is signalling to the world we have no interest in carving out our stake in the future. Any nation serious about competing in the modern world needs to understand the unique problems and advantages of scale, and address them.

Nowhere is this more strongly seen than in Amazon, arguably a company that deals with scale like no other. The sheer scale of co-ordination at a company like Amazon requires novel solutions which make Amazon competitive in a way other companies are not.

For example, Amazon currently owns the market on cloud services (one of the few places where a competitor is near the top, Amazon: 32%, Azure: 23%). Amazon provides data storage services in the cloud with its S3 service. Typically, data storage services have to handle peak times, when the majority of the users are online, or when a particularly onerous service dumps its data. However, Amazon services so many people – its peak demand is broadly flat. This allows Amazon to design its service around balancing a reasonably consistent load, and not handling peaks/troughs. The scale is the advantage.

Amazon warehouses do not have designated storage space, nor do they even have designated boxes for items. Everything is delivered and everything is distributed into boxes broadly at random, and tagged by machines so the machines know where to find it.

One would think this is a terrible way to organise a warehouse. You only know where things are when you go to look for them, how could this possibly be advantageous? The advantage is in the scale, size, and randomness of the whole affair. If things are stored on designated shelves, when those shelves are empty the space is wasted. If someone wants something from one designated shelf on one side of the warehouse, and something from another side of the factory, you waste time going from one side to the other. With randomness, you are more likely to have a desired item close by, as long as you know where that is, and with technology you do. Again, the scale is the advantage.

The chaos and incoherence of modern life, is not a bug but a feature. Just as the death of feudalism called humans to think beyond their glebe, Lord, and locality, the death of legacy media and old forms of communication call humans to think beyond the 9-5, elected representative, and favourite Marvel movie.

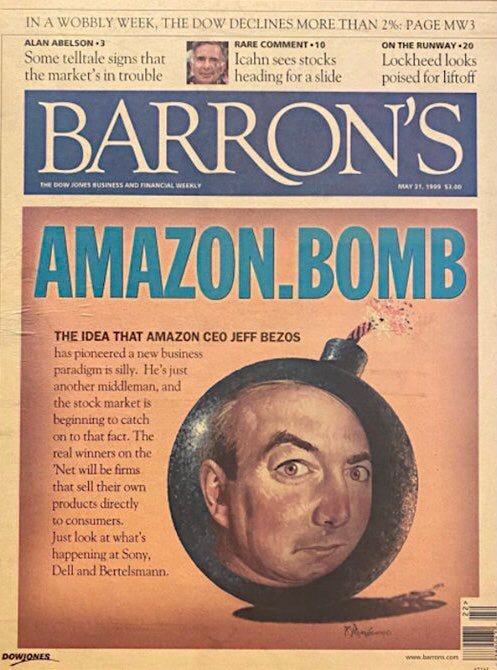

In 1999, one year after Amazon began selling music and videos, and two years after going public – Barron’s, a reputable financial magazine created by Dow Jones & Company posted the following cover:

Remember, Barron’s is published by Dow Jones, the same people who run stock indices. If anyone is open to new markets, it’s them. Even they were outmanoeuvred by new technologies because they failed to understand what technophobes always do: scale is the advantage. People will not want to buy from 5 different retailers because they want to buy everything all at once.

Whereas Barron’s could be forgiven for not understanding a new, emerging market such as eCommerce, there should be no sympathy for those who spend most of their lives online decrying growth. Especially as they occupy a place on the largest public square to ever occur in human existence.

Despite claiming they want a small-scale existence, their revealed preference is the same as ours: scale, growth, and the convenience it provides. When faced with a choice between civilisation in the form of technology, and leaving Twitter a lifestyle closer to that of the past, even technology’s biggest enemies choose civilisation.

Kino

Deconstructing Samurai Jack

Samurai Jack was an American animated TV series that premiered on Cartoon Network in 2001 and ran for, eventually, five seasons. The story follows the adventure of an unnamed samurai travelling through a dystopian future governed by a demonic wizard named Aku. What makes Samurai Jack unique is the moral paradigm that can be read into the central premise of the plot, neatly summarised by the tagline of the opening sequence: ‘Gotta get back, back to the past, Samurai Jack.’

The world that the samurai fights to destroy – a world corrupted at every level by Aku’s evil – is unambiguously modern in character. When he is cast through a time portal at the end of the first episode, he falls out into the squalid depths of a futuristic inner city ghetto. He drops out of the sky into a world of towering black skyscrapers, massive electronic billboard advertisements and sky-streets jammed with flying motorcars. The thunderous roar of the city’s traffic disorients and terrifies him.

After barely surviving his dramatic entrance, he is greeted by some locals who give him the name ‘Jack’ and speak to him in what is easily recognisable as a modern urban patois. ‘Yo, Jack! That was some awesome show!’ ‘Word! Jack was all ricochetically jump-a-delic!’ Their manner of speech contrasts heavily with Jack’s own old-fashioned and deliberately measured standard English. When Jack hesitantly asks where he is, he is told by these odd strangers that he is in the ‘central hub’ of Sector D. This is a placeless place, devoid of history or culture and labelled a ‘hub’ of a ‘sector’ in familiarly modern and soulless bureaucratic fashion.

Jack then stumbles into a seedy nightclub where he becomes even more distressed than before. He holds his hands to his ears, desperate to block out the loud, thumping techno music, and looks around wild-eyed at a room full of scantily-clad dancers and hideous aliens with bionic body parts. This new world is too bright and too loud for Jack. The world he came from is tranquil, soft and full of flower-filled meadows, rolling hills and beautiful snow-topped mountains. Aku’s world is vulgar, harsh and obnoxious. Jack is a man out of time, questing through the future in order to return to the past. He fights to turn the clock back in order to prevent the world around him from ever existing and to save the world he once knew. The tale of Samurai Jack is a reactionary, luddite Odyssey.

The first scene of the first episode is like something out of a bad psychedelic trip or a nightmarish fever dream. Everything is uncanny – the sun and moon are too large, the landscape is barren and red and the lone piece of flora in the scene is a twisted black tree. The giant moon eclipses the sun, shooting red lightning through the sky as the tree twists and morphs into the demon Aku. This terrifying moment, complete with deliberately unsettling sound effects, masterfully introduces the show’s main antagonist. It is also a prime example of Tartakovsky’s use of the environment instead of dialogue to evoke emotion and convey information about his characters.

Aku is able to see Jack through a magic mirror at all times, he can shapeshift endlessly and is immune to all physical weapons. Aku is more than a demon wizard – he is a malevolent god. He is informed instantly of Samurai Jack’s arrival in the future by his informant network that, throughout the show, seems to extend into every nook and cranny of the universe. Aku’s armies are inexhaustible, dwarfed only in size by the intergalactic mining operation he employs to sustain it. The entire universe is in the grip of an Orwellian state in the service of a quasi-Gnostic demiurge. The central premise of the show itself implies the extent of Aku’s dominance – dominance so complete as to be completely insurmountable, and able to be defeated only through time travel. Genndy Tartakovsky’s finest creation is a kids TV show set in a world that is incomprehensibly awful, where the main character faces completely hopeless odds and the main antagonist is all-powerful. Jack stands alone, armed only with a magic sword and the power of righteousness, and yet it somehow feels as though Aku fears him more than he fears Aku.

For the first four seasons Jack is an unchanging constant as the setting around him is repeatedly changed in line with his journey. Dialogue and character development are conspicuously limited in contrast to many other shows, but this speaks to the genius of Samurai Jack’s unique formula. The relationship between the main character and the setting are reversed – Jack is the unchanging stage. The story takes place around him but he stays the same, dressed in his characteristic white robes, forever a fish out of water. The only exceptions to this rule are the first episode, where Jack’s character is established, and the final season on Adult Swim, which takes a different and more mature tack.

Genndy Tartakovsky’s work for Cartoon Network is understandably constrained by limits of what is appropriate for children to watch before school, but when the show was moved to Adult Swim it became free to explore darker themes. For the first four seasons, Jack turns his deadly sword on his robotic and demonic enemies only. This allowed Tartakovsky to showcase Jack’s skill, defeating hordes of enemies that sometimes cover the entire horizon, without any graphic violence. The fact that Jacks opponents until the final season remain the minions of Aku, which are overwhelmingly robots, rather than the flesh-and-blood inhabitants of his fallen world is another way in which Aku and his evil are made to seem industrial in character, in opposition to noble, agrarian Samurai Jack.

The entire show is hand-drawn without outlines so that characters blend into their backgrounds. Lineless drawings give the animation a rudimentary, child-like appeal as well as greater flexibility with regard to proportions so that all of the characters’ movements feel powerful and dynamic. Action scenes are one of the great strengths of Tartakovsky’s cartoons – evident in Star Wars the Clone Wars (2003) earlier in his career right through to Primal, which aired just recently in 2019. All of this combined with the use of comic book-esque screen framing make the series feel more like a graphic novel come to life or an anime series than a Western kids cartoon. What’s more, Samurai Jack accomplishes this without sacrificing childish entertainment value.

However, what makes Samurai Jack stand out in a sea of well-animated cartoons is the story. Jack is a unique character that represents a sentiment not often explored in visual media – the sense of longing for a world you’re not even sure exists, or ever existed. The world around Jack is fetid and evil – but the world he remembers, was it ever truly as good as he remembers it to be? Was the world that was ever free of the corruption and evil that so disgusts him about the world – the ‘world that is Aku’ – that he fights to undo? Jack’s sense of alienation is deeper than that of a stranger in a strange land – he is a man trapped at the wrong place in time entirely. Not only is the world foreign, but everything is laced with and governed by Aku’s evil. The very ground on which he walks, the air through which he moves, is hostile to him. In our world where seemingly nothing can escape the plastic-coated grip of modernity, this cartoon asks whether it really is so crazy to feel like you’ve gotta get back, back to the past, Samurai Jack.

Against the Rationalists

I had forgotten why I wrote ‘Against the Traditionalists’, and what it meant, so the following is an attempted self-interpretation; for that purpose, they are intended to be read together.

The Preface of Inquiry:

God hath broke a motley spear upon the lines of Rome,

When brothers Hermes masked afront Apollo’s golden throne.

The Aesthetics of Inquiry:

Metaphors we hold in mind, those scenes with their images and progressions, are of the fundamental sense that orders our perceptions and beliefs, and from which everything we create is sourced; for metaphors are dynamic and intuitive relations; and they emerge from the logic of the imagination—let us have faith that our logic is not cursed and disordered, in its severance from the Logos. The phenomenologists would be amply quoted here if they weren’t so mystical and confused—alas, one can never know which of the philosophers to settle with as they’re all so sensible, and they can never agree amongst themselves, forming warring schools that err to dogmatism since initiation—so it is to no surprise that ideologies are perused and possessed as garbs regalia, and for every man, their emperor’s new clothes.

If brevity is the soul of wit, then genius is the abbreviation of methodologies. Find the right method of inquiry, for the right moment: avoiding circumstantial particulars, preferring particular universals; even epistemic anarchist, Feyerabend, would prefer limited, periodical design to persistent, oceanic noise. One zetetic tool of threefold design, for your consideration, might be constituted thusly: axiomatic logistics—Parmenides’ Ladder, founded, stacked and climbed, with repeated steps that hold all the way; forensic tactics—Poe’s Purloined Letter, ontologically abstracted over to compare more general criteria; panoramic strategy—puzzling walnuts submerged and dissolved in Grothendieck’s Rising Sea, objects awash with the accumulated molecules of a general abstract theory. Yet, do not only stick your eye to tools, lest you become all technique, for art, in Borges, is but algebra, without its fire; and let not poor constructs be ready at hand, for the coming forth a temple-work, in Heidegger, sets up the world, while material perishes to equipment, and equipment to its singular use.

Letters of Fire and Sword:

A gallery of all sorts of shapes, and symbolic movements, exist naturally in cognition and language, and such a gallery has it’s typical forms—the line and circle, for example, are included in every shape-enthusiast’s favourites—though Frye identifies more complex images on offer, such as mountains, gardens, furnaces, and caves—and, most unforgettably, the crucifix of Jesus Christ. I’d write of the unique flavours of languages, such as their tendency to particular genres, to Sapir and Whorf’s pleasure, yet by method I must complete my first definition—now from shapes, their movement. The cinematographic plot of pleasing images adds another dimension to their enjoyment—moving metaphors, narrative poetry, being the most poetic; their popular display is sadly limited to mainly the thesislike development of a single heroic journey, less so the ambitious spiral scendancy, or, in the tendency of yours truly and Matt Groening, disjointed and ethereally timestuck episodes in a plain, imaginary void. The most beautiful scenes, often excluded, are a birth and rejoice, the catharsis of recognition, and the befalling ultimate tragedy and its revelation to universal comedy—these stories hold an aesthetic appeal for all audiences, and that’s a golden ticket for us storytellers.

If memory is the treasurehouse of the mind, then good literature is food for the soul. In the name of orthomolecular medicine, with the hopes that exercise and sleep are already accounted for, let your pantry be amply stocked and restocked with the usual bread and milk, with confectionary that’s disappeared afore next day, and with canned foods that seem forever to have existed—as for raw honey, a rarer purchase, when stored right it lasts a lifetime, and eversweet. I’m no stranger to the warnings against polyunsaturated fats by fringe health gurus, but I think I’ll take my recommendations from the more erudite masters of such matters; and I’m no stranger to new and unusual flavours, provided they’re not eaten to excess. The canonical food pyramid of Western medicine, in its anatomical display of appropriate portions, developed from extensive study and historical data, places the hearty reliables en masse at its foundations, and the unhealthiest consumables at the tiniest peak, so that we might be fully nourished and completed, while spared of the damage wreaked on our bodily constitution by sly treats of excess fats, sugars, and salt. Be rid of these nasty invaders, I say, that’d inflame with all sorts of disease; be full of good food, I say, that’d sharpen the body’s workers to good form. Mark the appropriateness of time and place when eating to the same measure; a diet is incomplete without fasting—let your gut some space to rest and think. And note the insufficiency of paper and ink as foodstuffs, and the immorality of treating friends like fast food—the sensibility of a metaphor must be conducive to The Good as well as The Beautiful, if it is to be akin to The True. Aside, it is the most miserable tragedy that, for all the meaty mindpower of medieval transcendental philosophy, they did not explore The Funny—for the Gospels end in good news, as does good comedy.

Bottom’s Dream:

Shakespeare—The Bard of whom, I confess, all I write is imitation of, for the simple fact I write in English—deserving, him not I, of all the haughtiest epithets and sobriquets that’d fall short of godhood, writes so beautifully of dreams in Midsummer’s Night’s, and yet even he could not do them justice when speaking through his Bottom—ha ha ha, delightful. “I have had a dream, past the wit of man to say what dream it was: man is but an ass, if he go about to expound this dream. Methought I was—there is no man who can tell what. Methought I was, —and methought I had, —but man is but a patched fool, if he will offer to say what methought I had. The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report, what my dream was. I will get Peter Quince to write a ballad of this dream: it shall be called Bottom’s Dream, because it hath no bottom…”, Nick Bottom, from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. At the end of Act IV, Scene 1.

Intermission, The Royal Zoo:

A Prince and three Lords did walk in the garden, and they sauntered about for the day.

The soon-to-be-King became awfully bored and inquired what game they could play.

“Perhaps, Sire, it’d be best to prepare”, they said, “for life’s duties that approach”.

“It is proper to train for a life’s work”, said they, “lest that debts’ hunger encroach”.

“Consider the rats”, said the Money Lord, “how they scavenge and thrift for tomorrow”.

“For their wild life is grim, and tomorrow’s tomorrow, so take what you can, and borrow”.

“Consider the lions”, said the Warrior Lord, “how they prowl and sneak for a bite”.

“For the proud life is hearty, strong conquers weak, lamb shanks easiest sliced at night”.

“Wise, yet consider the spiders”, said the Scribe Lord, “for they outwit both lion and rat”.

“To scavenge is dirty and timely, and hunting so tiring, better cunning employed to entrap”.

The Prince, unsatisfied by his Lords, summoned a Squire to ask of him his opinion:

“Squire, what do you do, not yet enslaved by your profession, that maketh life fulfilling?”.

“I play with whom I play, and with whom I play are my neighbours, my friends”, said Squire.

For that, said The Prince, “I will live not like a beast”, “I will live like a man!”,

And three Lords became three furnaced in fire.

“Then I commended mirth, because a man hath no better thing under the sun, than to eat, and to drink, and to be merry: for that shall abide with him of his labour the days of his life, which God giveth him under the sun.”, Ecclesiastes 8:15, KJV. Amen.

The headstar by which we navigate, fellow Christians, is neither Athens nor Rome—it is Christ. “Be sure [Be careful; Watch; See] that no one ·leads you away [takes you captive; captivates you] with ·false [deceptive] and ·empty [worthless] teaching that is ·only human [according to human traditions], which comes from the ·ruling spirits [elemental spiritual forces (demons); or elementary teachings] of this world, and not from Christ.”, Colossians 2:8, EXB. Amen.

A Note on Opinion:

It is common sense, in our current times, that the most opinionated of us rule popular culture. Without a doubt, the casting, writing, directing, etc, of a major cinematic production project is decided in final cut by ‘the money’—so I speak not of the centrally-planned, market-compromised popular-media environment—but it is by the algorithm of the polemic dogmatist that metacultural opinions, of normative selection and ranking and structuring, are selected. One must be at the very least genius, or prideful, or insane, to have the character of spontaneously spouting opinions. It is an elusive, but firmly remembered anecdote that ordinary, healthy people are not politics-mad—ideologically lukewarm, at the very least. Consider the archetypical niche internet micro-celebrity: such posters are indifferent machines, accounts that express as autonomous idols, posting consistently the same branded factory gruel, and defended by their para-socialised followers over any faux pas, for providing the dry ground of profilicity when sailing the information sea. Idols’ dry land at sea, I say, are still but desert islands—houses built on sand. Now consider the archetypical subreddit: ignoring the top-ranking post of all time either satirising or politicising the subreddit, and the internal memes about happenings within the subreddit; even without the influence of marketing bots, the group produces opinions and norms over commercial products and expensive hobbies, and there is much shaming to new members who have not yet imitated and adopted group customs; essentially, they’re product-review-based fashion communities. Hence, the question follows: if knowledge is socially produced, then how can we distinguish between fashion and beauty—that is, in effect, the same as asking how, in trusting our gut, can we distinguish lust and love? How can we recognise a stranger? Concerning absolute knowledge, including matters of virtue and identity, truth is not pursued through passion’s inquiry, but divinely revealed. “Jesus said unto them, Verily, verily, I say unto you, Before Abraham was, I am.”, John 8:58, KJV. Amen.

A Note on Insanity:

It is common for romantic idealists to be as dogmatic as the harsh materialists they so criticise. All is matter! All is mind! One ought to read Kant methinks; recall Blake’s call to particularity: there needs be exceptions, clarifications, addendums, subclauses, minor provisions, explanatory notes, analytical commentary, critique, and reviews—orbiting companion to bold aphorism; Saturn’s ordered rings, to monocle Jupiter’s vortex eye, met in Neptune’s subtle glide. Otherwise, the frame is no other than that which is criticised: arch-dogmatism. If we’re to play, then let us play nicely; it is not for no reason that Plato so criticised the poets, for the plain assertions of verse do not explain themselves, and so are contrarywise to the pursuit of wisdom in a simple and subjectivist pride—selfishly asserting its rules as self-evident. Yet, they might be wedded, for truly there is no poetic profession without argumentative critics—no dialectic without dialogue. And so, if I must think well, and to accept those necessities, then questions of agency be most exhaustive nuts to crack. If all is matter, then all is circumstantial—If all is mind, then all is your fault; if all is reason, we’re bound by Urizen’s bronze—if all is passion, we’re windswept to fancy. Unanswered still, is the question of insanity. And even without insanity, what is right and what is wrong so eludes our wordy description. “So whoever knows the right thing to do and fails to do it, for him it is sin.”, James 4:17, KJV. Amen.

Endless curiosities might unravel onwards, so shortly I shall suggest a linguistic idealist metacritique of mine own, that: to make philosophy idealistic, or to naturalise the same, are but one common movement, merging disparate literatures representing minds, of the approach to total coherence of the human imagination; such that might mirror the modal actualism of Hegel, a novelist who was in following, and ahead of, the boundless footsteps of short story writer, Leibniz. To answer it most simply: for four Gospels, we have fourfold vision, so if one vision is insufficient, then two perspectives are too—all-binary contradiction is the workings of Hell, but paradox and aporia, is, as exposited by Nicholas Rescher and Brayton Polka, the truth of reality. This way we might properly weigh both agency and insanity, by taking the higher ground of knowledge and learning. Recall Jesus’ perfect meeting of the adulterer—when he saw the subject and not the sin.

A Note on Disability:

There is potential for profound beauty in the inexpressible imagination, such that would make language but ugly nuts and bolts, if it didn’t also follow that we cannot absolutely explicate language either. Then, it seems even if our words do not create the world, but are representations, we can still know and appreciate facets of reality without their full expression—our words construct models, or carve at the joints of the world, but the good and beautiful expression is true proof of God; to recognise truth is intuitive, perhaps being that mental faculty which is measure sensibility. Hence, let us first pray that we are all forgiven for our sins, ignorant and willing, and second, that the mentally disabled, and lost lambs without dreams, can know Him too. Amen.

Conservatives can learn from modern art

You’re probably already baulking at the idea that there could be anything to learn from modern art. You’re not wrong that art and architecture today are often hideous, lazy, cheap, unconsidered, and, well, artless. It won’t help that I myself am still not completely concluded on what there is to learn. Alinskyite tactics of making the enemy live up to their own rules? Did Duchamp just encourage the wrong kind of person and end up making things worse? More on this later.

But there is something in modern art worth considering, it’s not a total waste, you must take wisdom wherever you can find it. There is so little wisdom going. You can’t afford to waste any. Your opponents in the progressives are powerful, rich, and vicious, in all senses of that word. Many, many, many are also group-thinking chasers of convention, out of touch, fearful, vain, and insecure. They don’t believe in the truth, something eternal, irrespective of them, they believe in their truth, as if it emanates from themselves. A pretentious way of saying they want to express their feelings? Perhaps. But truth for them is decided by consensus and fitting in. Yup, that’s the art scene progressives for you.

That’s good, that’s a massive weakness. How do you exploit it? How do you handle these people? It’s risky, but people who stand out, do not follow the crowd, have the self-confidence to go their own way, and the actual knowledge and mastery to do it competently, are cool. A big part of what the art scene progressives want to do is fit in and be cool. The risk is that what’s cool, or even just true, for them is decided by consensus, not reality.

Art, religion, politics, Rob Henderson’s luxury beliefs. What’s the overlap and what can you learn from one to the other? Dismiss all of modern art, if you like, but at least keep one artist. So much which comes after him is basically derivative and misses the point. Let’s follow a master, see what he did and why, and draw out the lessons. You too will make progressives clutch their pearls and faint, or pop their monocles, and exclaim “harumph, why, that is most unorthodox!”

Marcel Duchamp. He is exactly the right kind of figure to look at. Where to start exactly?

Marcel Duchamp is a tricky sort. You could say he was a total troll and he would often go out of his way to obfuscate history by making things up when asked about his work. He was a bit of a prankster, and he liked tinkering with all the new mediums of his day. He was unpredictable.

And modern art. Where to start exactly with that? Not all contemporary art is synonymous with modern art. If that’s not quite difficult enough, it’s not fair to describe all modern art as crap. At least you might concede it’s not all crap in precisely the same way. It’s a low standard, but a place for you to start.

It’s kind of like memes. They’re often highly context dependent, assume some level of preceding knowledge, are trying to say something to the person who sees them, and some memes are better than others.

Similarly, Duchamp is a man of his time. He was clearly interested in technology, and why wouldn’t he be? He’s around at the time of the wireless, new elements and other discoveries coming out of Marie Curie’s laboratory, the invention of cinema, and x-rays. New materials, new mediums, new ways of getting a different insight into the world around you. New ways of thinking. In physics and mathematics Einstein displaces Newton, non-Euclidean geometry bursts forward, the first thoughts about different dimensions. And it’s all happening around WWI, the ends of empires, the international rise of America, and the replacement of Europe’s monarchies.

What is analogous to any of this today? The internet, AI, social media, NFTs, space? New possibilities, new technology, new materials, new politics, it forces people to question things.

Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2

Duchamp’s first important piece: Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, an example of cubism, with caveats, because it upset some people.

Some context. Let’s quickly look at the Italian futurists in the 1910s, which started with Marinetti.

The futurists were pretty hard core right wingers (Marinetti co-wrote Il manifesto dei fasci italiani di combattimento), who were obsessed with technology and machinery. They wanted to scrap museums, libraries, forget the past, in favour of a world dedicated to speed, and strength, and the future. Is this what made the trains run on time? Anyway, artistically, they were interested in capturing energy and motion in two dimensions. And it was looking to have something to say. What a lot of people don’t fully appreciate about modern art (you were warned this would get pretentious), is that it involves audience participation. If you’re saying “WTF am I looking at here?”, you are saying a response to the piece.

Before modern art, you have realistic art. Actually, realism, which is what it sounds like. Technology by the 1910s keeps getting more and more advanced, and you have more cameras, and photos, and films, at the time artists were beginning to question the point of a realistic painting. Modern artists were rising to that challenge.

Whether it’s futurists, or dadaists, or surrealists, which all emerge around this time, they’re trying to deal with the paradigm shifts of their day. What are the artists of today up to? How many of them are energised and engaged with the paradigm shifts of our day?

The point is, a lot of art, especially modern art, is contextual, just like a lot of culture, whether it’s stories or music, movies, etc. to fully appreciate its impact you really have to be there and part of it. This goes beyond art, well into politics. How do you explain the world pre and post 9/11 to those who weren’t there? The New Atheism movement made more sense in the face of religious extremism, whether that was muslims like bin Laden or evangelicals like Bush.

Modern art emerges amid two world wars, and the blossoming of progressive democracy and its three fruits; communism, facism, and liberalism.

The futurists believed that war is the world’s only moral hygiene, a chance to start anew, that art gets shifted into the new world it brings forth. And then rather a lot of them died in WWI and that was more or less that.

Now, here comes a particularly important thing. A bunch of these art movements would come with manifestos. That is, instructions for how art is and isn’t supposed to be. Rules for what you could and couldn’t express and in what way. The simultaneous scrapping of the past, obsession with what’s new, a certain reverence for violence and domination, and replacement with a new hierarchy. No rules, and also rules, and lots of angry people. Does that sound familiar to you at all, duckies? Have progressives been the same for a hundred years, maybe more?

Well, when art comes with rules, and particularly about what it is supposed to say to people, that is almost certainly propaganda. Oscar Wilde might have had something to say against this (The Picture of Dorian Gray), or Kim Il Sung in favour, as Juche art is supposed to carry a moral, political element to it.

Can we forgive the futurists? They were working before the full, crushing horror of the progressive 20th Century.

Anyway, Duchamp’s Nude changes the art movement of his time, challenges it, mocks it. The full saga of the Nude takes place over a couple of years. He presents it at the pretentiously named (the progressives are all very self-congratulatory aren’t they?) Salon des Indépendants where the cubists reject it. Remember that art is supposed to be full of rules? Cubism is supposed to be about multiple dimensions portrayed simultaneously. Futurism is supposed to be about motion. The Nude is both. Oh no, what a disaster! Most unorthodox!

So, in 1912 some exhibits were supposed to happen at the Salon des Indépendants. The futurists came first, that was all lovely, and the cubists were supposed to come after. Some of the smaller cubists came together to do their own thing and have an “art movement”. Duchamp was having none of it.

The first thing the cubists had a problem with was the title, but Duchamp puts the title right in the painting, so it can’t be hidden, removed, changed, disguised. Total troll. He’s also trying to play with language. It was originally titled “Nu descendant l’escalier” in the literature, and “Nu” is ambiguously male. Worse still, nudes are supposed to be painted lying down, like one of your French girls. Nudes aren’t supposed to be descending stairs. What’s more, the only place naked women were likely to be descending stairs in Paris was at brothels or Mallard Chairman Jake Scott’s mum’s house.

All round, the hanging committee (not as ominous as it sounds) for the exhibit were totally scandalised. Have a look at the painting again. Yup. Duchamp was told to change it, the title was wrong, the painting was too futurist, too Italian, just no good, so he left and removed himself from the show. Something similar then gets repeated in 1913 at the Armory Show in New York.

So much for artists being open-minded or intellectual. Then again, are you surprised that there’s a lot of snobby arseholes in the art world who get bitchy?

Still, Duchamp had the last laugh. Who else out of the cubists exhibited at the Salon is remembered as well today? In Duchamp’s own time, at the Armory, the next year, he was peer level with Picasso as a cubist, and other artists such as Matisse, Delauney, Kandinsky, Rodin, Renoir, and others.

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

Alright, so where can Duchamp go from here? His next piece, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, is an even further descent into top notch trolling.

Duchamp really wanted to get into the idea of the fourth dimension with Bride, in the geometric, not temporal sense.

In three dimensions, you can imagine a point within a three dimensional cube and create a coordinate for it along width, height, and depth. A fourth dimensional point would sit in relation to all three of those – it might be like if you could see all sides of the cube and its inside at the same time. And if this four dimensional shape could cast a shadow, it would be a three dimensional shadow, just like a three dimensional object casts a two dimensional shadow on a wall, for example.

The idea was that if you could put three dimensional reality into two dimensions in a painting, what is a three dimensional piece a step down from? You can’t seem to make it real, exactly, so you have to sort of imagine it instead. Can you imagine a tesseract, the fourth dimensional equivalent of a cube? Here’s a representation of the concept.

For a two dimensional painting, it should come very naturally to you to understand what three dimensional object or scene it represents. For any of you duckies who have spent time thinking about non-Euclidean geometry, perhaps Bride might come a bit easier to you.

Or not. But it’s a commendable attempt at trying something new from Duchamp.

So, yes, you will definitely look at it and think WTF is this, but this is very much by design. Though he started the piece in 1915, and it would go on exhibit 12 years later in 1927, he would later publish notes in 1934 as an accompaniment. He did not want a purely visual response.

How did this take him so long to complete, you ask? His patrons said they’d pay his rent until he finished.

Now, at this point you’re probably asking a very justified question. How much is Duchamp really just a bullshit artist? Well, that’s a kind of art too. He’s at least a little funny, a little clever, and a little daring. Can the same be said for progressives?

Duchamp at this point is experimenting. He’s playing with chance. Art is usually done very deliberately, but is it possible to create something through other methods? Are you limited in your materials? Is it possible to use abstract concepts themselves to make something? Is it sometimes more interesting to achieve something that you didn’t exactly set out to do?

There are a few replicas of Bride. The original in Philadelphia is broken, it broke on its way to the original exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. The ones in Sweden and Tokyo are not broken, and are a different experience. They’re also all getting a bit worse for wear. Duchamp didn’t necessarily make things to last. That wasn’t important. His personality itself is perhaps more the figure, more the legacy, than any of his works.

Disposability and personality? He would have been perfect in today’s world of memes, social media, and reality TV. Self-belief, showmanship, fake it til you make it, bullshit artistry. Politicians are memed into success these days. This kind of chaos, flexibility, fun, unpredictability, is not open to the progressives. They have a hegemony to conserve. You have a hegemony to subvert.

You could do worse than to learn from Duchamp.

Fountain

Oh boy. Duckies, if I haven’t lost you already, this one might do it.

Duchamp is in America at this point. America, unlike Europe, has no real history at this time. Plus ça change. (French. You were warned this would get pretentious). Are there lessons to learn here about the internet and the internet generations? Not sure, perhaps you can think about that one.

Anyway, a lot of artists go to America because of the war and Duchamp is asked to run a show. The New York art scene wants to replicate the show Duchamp’s Nude was kicked out of. The Americans want to have a go at their own Independence. How derivative. So, two of the conditions for the show was that there was to be no jury and no prize. It’s like the Oscars. There are no winners. “And the award goes to…”. You can’t have winners. That would imply some people are better than others. No, jury, no prize, nothing is better than anyone else, but it’s still a selective hoighty toighty art show. All the artists who kicked Duchamp out of the 1912 exhibit will be there. Duchamp detects an opportunity.

He takes a urinal, signs it R Mutt and, sure enough, it is kicked out of the show. But it gets photographed.

Duchamp is making another mockery, running another test here. Why can’t a nude descend a staircase? Who made these rules? Who makes art rules? A lot of the audience had never even seen a urinal before, which makes it even funnier.

Duchamp is working with context. Everyone sees a toilet every day. Even prissy art snobs. You can’t look at one in an art exhibit? Why exactly? It’s extreme, sure, and you wouldn’t be impressed with it, duckies, but you’re not pretending to be progressive and egalitarian and open and free or whatever. Duchamp puts a toilet right in the middle of a fancy shmancy art show for all the people who are up themselves for reasons they don’t understand and they lose their minds.

And to this day, people are still debating whether it’s art. In today’s digital economy, when so much is abstracted – social interaction, work from home, shopping, entertainment, etc, – this debate is as relevant as ever.

Really this is about the governing classes, who today are the progressives. If you don’t understand three things by now, you really ought to. First, the ruling class don’t care about the rules in the same way many of the governed do, because they make them, know why they’re there, and what they’re trying to do with them, for power. Second, a lot of the governed really don’t know why their rules are there, but follow them anyway, for many reasons, and only care about the rules at the surface level. Third, a big chunk of the middle class gets up itself precisely because they’re not in the ruling class, are close enough to sniff it, can see it, want it, but aren’t truly in it, and don’t fully understand it.

The most important thing about Fountain is that Duchamp has a sense of humour. It’s even funnier that there was only one photo at the time, the Fountain now is just a replica, and nobody has even seen the original for 50 years. We don’t actually know if Duchamp was making everything up.

Duchamp used to make stuff up in TV interviews. Performance artist? Certainly an early iteration of it. It’s not just enough to subvert the progressives in your work.

You must live it.

Readymades

Well, one in particular. L.H.O.O.Q., which is basically a meme.

The readymades were more or less mass manufactured products which Duchamp sort of took, made a few alterations to, and declared pieces. Yup, that’s a meme. Fair use!

L.H.O.O.Q. is a picture of the Mona Lisa with a moustache and goatee drawn on. Factory produced graffiti? This is 40 years before Warhol, and how long before Banksy? L.H.O.O.Q. was only possible because of advances in technology.

The readymades are a tension between art and not art (pretentiousness continued) – you can go to a museum, look at an exhibit with a urinal set with a sign saying “do not touch” then go into the bathroom and do rather a lot more than touch. The question for you is why is one thing there and not the other? The Mona Lisa (the real one) is there because it obviously should be there?

The answer is “yes”, btw.