Zak Mudie’s article in this publication on 11th December 2021 piqued my interest more than articles or opinion pieces usually do, for its rather bold argument that the United Kingdom should rid Parliament of its sovereignty and instead pursue a separation of powers. Far from being cautious and pragmatic, as Mr. Mudie claims, I find this proposal markedly incongruous with the accumulated traditions and conventions of the British political system which have served this nation so well for centuries. This is not to say I disagree entirely with his analysis, since I do not, but I think an alternate survey of the problems of and potential reforms to our modern Parliament would be nonetheless beneficial. I intend to conduct the rest of this article in a somewhat similar order to Mr. Mudie’s as to not roam too far away from the subject, but with certain digressions where apt.

Whilst I would also consider myself a traditional conservative, I am far less pragmatic and a tad more radically inclined than Mr. Mudie. Pragmatism is an anti-ideology, one of those isms which will absorb everything surrounding it until it alone remains. Indeed, most of the ideology of the modern Conservative Party has fallen into this black hole, perhaps never to return, under the guises of ‘modernisation’ and extending the lifespan of impotent governments. Therefore, pragmatism should be used in moderation and out of necessity rather than as a first resort, lest one wishes to be permanently unsatisfied by reform. After all, politics is ultimately about winning.

However, Mr. Mudie is right to question our modern political institutions and whether they effectively serve their goals. Crisis or not, such an activity remains healthy for all those who wish to conserve this nation. The strange times we are living in have acted as a sort of stress test for our institutions and their members, and in that sense most have sadly failed to protect this nation. The content of the laws our representatives now pass, the manner in which they do so, the alien approach to liberty they repeatedly endorse, all run roughshod over our national traditions and what is democratically proper.

Yet I do not see parliamentary sovereignty per se as the root of this problem. In lieu of the true Sovereign, Her Majesty the Queen, political sovereignty is vested in the electorate via Parliament. This has been the case in one form or another since the Glorious Revolution of 1688 shifted the then-Kingdom of England firmly onto the path of constitutional monarchy. The “absolute power” of the House of Commons, though, is a more recent invention and this supremacy can and does cause problems.

Edmund Burke once discussed the “limits of a moral competence” when Parliament was faced with filling the vacated throne of James II during the Glorious Revolution. Parliamentarians could have “wholly abolished their monarchy, and every other part of their constitution,” as was theoretically their prerogative during that moment of parliamentary supremacy, but they did not out of convention and principle. Presently, the respect and deference to the true foundations of this Kingdom and its people, which should be requisite of anyone wishing to have power over its constitution, is clearly lacking in many of our representatives. I am afraid that means the problem at hand is one where a majority of the House of Commons no longer share the same convictions as our politicians once possessed, resulting in Mr. Mudie’s core issue of its prolonged supremacy.

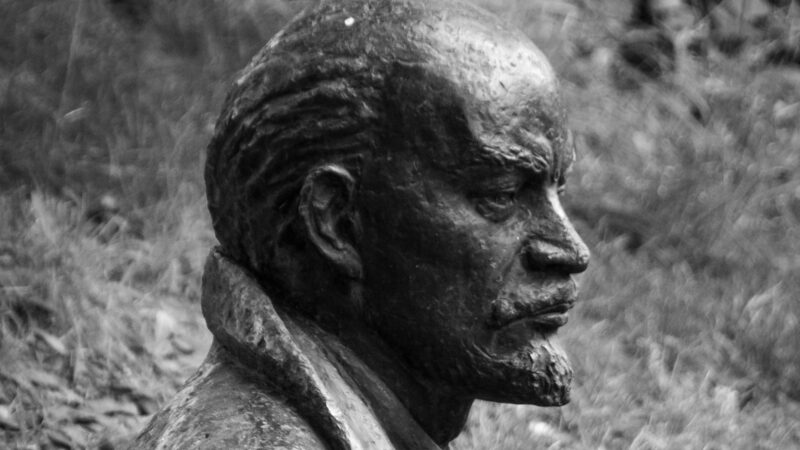

Armed with this realisation, one can start identifying the symptoms and consequences which the decline of the British politician has wrought on the political system. The British constitution, after all, is now but a forest of felled mighty oaks, their leaves littered all around for those who dare to see them.

For one example, allow me to divert one’s attention to the other half of Parliament. The House of Lords used to be something far more useful and dignified than the ermine-clad purgatory for cronies and ex-ministers it mostly serves as today. Burke believed it was “not morally competent… to abdicate, if it would, its portion in the legislature,” yet such is the incompetent eventuality which has nonetheless graced this country. The impatience of the Commons crippled the Lords through the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949, seizing the second chamber’s veto and then reducing its power to delay bills. If the Acts are invoked, which has occurred several times, it removes the requirement for the Lords to approve of a bill at all. The Life Peerages Act 1958 all but assumed the monarch’s power to create peers and enabled the flood of life peers in a less than ideal example of modernisation, whilst the House of Lords Act 1999 gutted the Lords Temporal out of thinly veiled spite and Blairite revolutionary zeal. To add insult to injury, the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 extracted the judicial functions from the Law Lords, depositing them into an America-lite Supreme Court in the name of the equally foreign concept of a separation of powers.

Returning to the subject at hand, I think Mr. Mudie nearly reaches the same conclusion I have on the House of Commons with his discussion of the double-edged sword our constitution provides for our liberties. If the standard of our politicians were higher and their knowledge of this Kingdom’s political heritage richer, I doubt this double-edged sword would need to be considered with the intensity recent events might justify. Mr. Mudie identifies several other benefits and flaws of parliamentary sovereignty and our unwritten constitution in his article, but I think we would both agree those necessitate representatives of a certain calibre to handle responsibly before arguing about reform.

Obviously, Mr. Mudie and I diverge substantially over alternatives to the current state of affairs. As I mentioned earlier, I consider the separation of powers a foreign concept to British political tradition because a polity as old as this should never be artificially divided. Such things are simply incompatible with organically evolving systems such as ours, which is why the Blair revolution has caused so many of this nation’s present problems. In essence, the United Kingdom should only ever be a modern democracy in the literal sense of being democratic and existing in the modern day. To adapt Walter Bagehot, only the utilitarian “practical men who reject the dignified parts of government” would pursue a modern democracy because our constitution’s dignity yearns for true constitutional monarchy.

As for laws, the English tradition of common law suffices for rules which benefit and protect the people. Although trampled by such Blairite semi-codification efforts as the Human Rights Act 1998, I believe the common law tradition stands ready to be reinvigorated. As for some “fundamental laws” against the power of government, our history shows this has emerged through the centuries without the need for a codified constitution. Swathes of our liberties have been gained in opposition to and as limits on the monarch’s power. This concept of negative liberty has served the people well in the past and if given the space to flourish it could yet further. Furthermore, Mr. Mudie’s proposal to hand emergency powers to the executive during a crisis would not look too dissimilar to the situation we have at the time of writing, given the rot of poor governance knows no bounds in the modern British political system.

Therefore, the alternative I would propose is one of constitutional restoration wherein Parliament’s sovereignty is maintained but the House of Commons’ supremacy is curtailed. I hope I have proved, at least in part, that a system once existed which worked well and would assuage Mr. Mudie’s valid concerns. Far from synthesising a Frankenstein liberal democracy out of a myriad of other dysfunctional exhibits plaguing the modern West, we should gaze back at the accumulated wisdom of centuries of politics with some inspiration and faith that it might orient us towards a brighter future. Pragmatism actually has a place in such a paradigm shift insofar as whatever can be salvaged from this current system should be.

As long as those with power are either indifferent or hostile to this country, parties will continue to populate Parliament with bootlicking careerists and jumped-up student union activists alike. Until the political paradigm of decline the United Kingdom finds itself choked by is utterly destroyed, next to nothing can be conserved and Parliament will continue to damage the people they serve from simply lacking the wherewithal to understand the political traditions they have inherited. A separation of powers, devolution or any other such scheme will not stop the apparatchiks and bureaucrats from grasping at ever more of the people’s rights and liberties. The Blob, simply lacking the moral competence of our forebears and working in lockstep with many politicians, will continue to consume everything still worth conserving until they become scattered arrays of hollowed out and meaningless shadows. The time for slowly changing to conserve a losing battle has long passed. Instead, the time is upon us for radical change to restore the political system of the country we love.