Rishi Sunak: MP for Anywhere

In his 2017 book, The Road to Somewhere, David Goodhart sought to explain the Brexit vote, and the furore that followed, as a rift between two tribes in British life: ‘Somewheres’ and ‘Anywheres’.

Somewheres, Goodhart explained, are traditionally-minded and attached to place. By contrast, Anywheres are cosmopolitans and attached primarily to ideals. Somewheres are often provincial and typically live in (or nearby) the communities in which they were raised. Anywheres are primarily urban and often live far from where they were raised.

For Goodhart, Brexit was a revolt of the nation’s Somewheres. Alienated by the extraordinary rate of social change in the post-Blair era, they took a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to vote against the Anywhere-dominated political establishment.

Though nominally a vote on Britain’s membership of the European Union, the referendum was essentially a vote of protest against the cross-party consensus on immigration.

The frustration of Somewheres is exemplified by voters in ‘The Red Wall’, a patchwork of traditionally Labour-supporting northern constituencies, who voted Tory en masse in the 2019 general election in the hope that Brexit might finally be settled and migration numbers could be reduced.

Though no less baffled than the rest of the establishment, The Conservative Party – unlike many of their fellow Anywheres – was willing to implement the referendum’s result. Ultimately, however, the failure to capitalise on the opportunities presented by Brexit, the collapse of the Red Wall, and a major electoral realignment was to define our outgoing government.

None personified this failure to understand the significance of Brexit as much as the man who was destined to lead the Conservative Party into the most recent election. This would not surprise readers of Goodhart’s work, for Rishi Sunak is Anywhere incarnate.

The hyper-conscientious child of immigrant parents who, through hard work and talent, has risen to the very apex of his profession, Sunak personifies the cosmopolitan ideals of the contemporary western elite.

Sunak’s failure as Prime Minister does not reflect a lack of merit. Of the four Prime Ministers who succeeded Cameron, Sunak was probably the most capable and accomplished.

Sunak’s relationship with his heritage is interesting. Born to Ugandan-Asian parents, Sunak exemplifies the industry and drive of that entrepreneurial group of people. Teetotal and vegetarian, our erstwhile leader married outside both his caste and ethnicity – of Punjabi heritage, his wife is the only daughter of a fabulously wealthy family of south Indian origin. In this he typifies the subcontinent’s elite diaspora who, as Razib Khan writes, have globalisation ‘etched in their bones’.

His heritage aside, Sunak’s background is that of a stereotypical Tory frontbencher. A product of Winchester College (where he was Head Boy), Sunak progressed to Oxford (where he earned a 1st in PPE) and thence to Stanford (via a Fulbright Scholarship).

Upon graduating, he pursued a career in high finance, first at Goldman Sachs and then at two hedge funds, the latter being based in California. Notoriously, Sunak filed US tax returns while serving as the Chancellor of the Exchequer, not relinquishing his Green Card until 2021.

Having joined the Conservative Party following an internship at Central Office, Sunak became an MP in 2015, replacing William Hague as the representative for Richmond. Parachuted into Number 10 in the aftermath of the Truss debacle, Sunak proceeded to dismay colleagues with displays of poor political judgement, choosing to announce the cancellation of a trainline to Manchester while in Manchester, to cite but one of several notorious examples.

Whereas for most the office of Prime Minister represents the culmination of a long and bruising career; Sunak’s brief tenure as Prime Minister will likely represent just another impressive (though relatively ill-remunerated) entry in a glittering CV. It is safe to presume that, before the Tories are again returned to power, he and his family will decamp to California in order that he might resume his career in finance.

For all the bluster about his supposedly reactionary politics, Sunak’s values align with the managerialist liberalism which dominates the contemporary Conservative Party.

The Economist describes Sunak as ‘the most right-wing Conservative leader of his generation’ and claims his ‘nerdy demeanour covers an overlooked fact… [o]n everything from social issues, devolution and the environment to Brexit and the economy, Mr Sunak is to the right of the recent Tory occupants of 10 Downing Street’, but this is merely relative.

Objectively speaking, similar to his background, Sunak’s politics are blandly Anywhere, believing that a modern economy cannot function without high levels of immigration – derived from his instinctive belief in entrepreneurial mobility – and extols ‘diversity’ as both a moral good and political virtue, even at the expense of factual accuracy.

Sunak’s support of Brexit, often cited as evidence of his right-wing convictions, is misconstrued. Sunak was no ‘Little Englander’ hoping to make Britain’s borders more restrictive. Rather, Sunak saw leaving the EU as an opportunity to further liberalise Britain’s immigration regime.

With Sunak gone, the Conservative Party is once again presented with the opportunity to reinvent itself.

For a generation or more, the Conservative Party has simply failed to take the concerns of Middle England seriously. Sunak, so removed from the concerns of ordinary British people that he didn’t think it worthwhile to attend ceremonies marking the 80th anniversary of D-Day, exemplified this detachment.

If the Tory party is to regain political relevance, it must listen to the nation’s Somewheres – a constituency that remains in flux, and that the Labour Party does not speak for. The lack of enthusiasm for our incoming government is remarkable and telling. The electorate has grown tired of the Tories, but are dubious of a Labour Party who seem to offer nothing but more of the same.

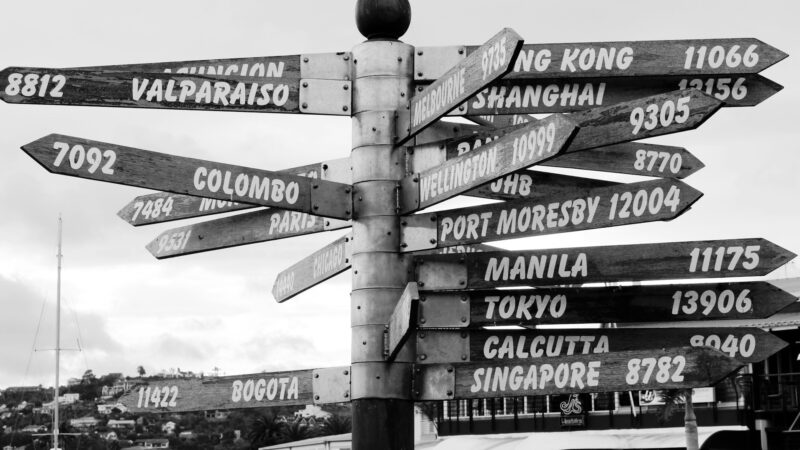

So farewell, Prime Minister Sunak. We wish you well, Anywhere you go.

Little England: Bekonscot, Le Corbusier and the Housing Crisis

The Morris men stand, hankies aloft, in the same pose they’ve held for decades. The little girl tugs at her father’s sleeve.

“Who are they, daddy?”

Her father pauses for a moment, scratches his chin and ventures a guess.

“They’re Irish dancers.” He says, “I think.”

The girl looks confused.

“I mean, I don’t know why they’re wearing lederhosen.”

Puzzled, he contemplates the scene further. I walk on.

BEKONSCOT

In 1927 Roland Callingham’s wife, tiring of her husband’s toy railway, insisted that he take his trains outside. Callingham, a well-to-do city accountant, purchased four acres of land on the outskirts of the Buckinghamshire town of Beaconsfield and, with the assistance of his gardener, W.A. Berry, began work on a model village, complete with a high street, church and railway, each constructed at the scale of one inch to one foot. Callingham dubbed his creation ‘Bekonscot’.

Originally intended as a private diversion, Bekonscot opened to the public in 1929, and soon became a popular tourist attraction, incorporating, in time, seven model villages. Initially, Bekonscot kept pace with the changing architectural styles of the times. However, a reactionary purge in the 1990s saw most modern buildings removed and the villages returned to a thirties aesthetic. Thus, what was originally conceived as a chance to see the everyday world in miniature, is increasingly a museum of a bygone Britain. Notably, the villages’ high streets are devoid of the vape shops and Turkish barbers that lend colour to the contemporary streetscape. Today, concessions to modernity are confined to a handsome Art Deco tube station, a few authentically drab office buildings and some token Arts and Crafts houses.

‘THE BEAUTIFUL’

The week before I visited Bekonscot, the government, determined to accelerate the rate of housebuilding across Britain, announced plans to build 300,000 new homes annually. Earlier in the summer, Angela Rayner announced plans to drop a requirement that new houses be ‘beautiful’, dismissing the old rules as ‘ridiculous’. ‘Beautiful’ explained Rayner ‘means nothing, really.’

For our deputy prime minister; her mind addled, like most of her generation, by postmodernism; ‘beautiful’ is a concept too subtle to be reduced to simple language, and as such, is essentially meaningless. For the modern liberal, ‘beauty’ can be filed alongside ‘female’ and ‘nation’ as terms too slippery to contain meaning.

This does not mean that the Angela Rayners of the world fail to recognise beauty (or, for that matter, ugliness) when they see it. It is rather that they have taught themselves to disregard the evidence of their eyes and dismiss all aesthetic judgments as purely subjective. But how smart must one be to understand that the average street in Salisbury, say, or Stratford-upon-Avon, is more beautiful than its equivalent in Salford or South Croydon? This is a truth that I am sure even Angela Rayner would acknowledge, if pushed.

FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION

Why, among those less sophisticated than the average Labour cabinet minister, is ‘modern’ often a synonym for ‘ugly’? There is no reason why contemporary buildings should not be beautiful. Modern architects can do ‘spectacular’ well – witness London’s ‘objects’ – the statement buildings that litter the City and Docklands. But such edifices, no matter how impressive, do not belong to any regional or national tradition. The Gherkin would not look out of place in Los Angeles, say, or Lagos. Further, every ‘object’ is an experiment, and if it fails to pay off, a city must live in its shadow.

By contrast, tradition makes for attractive architecture. Ugliness is seldom worth repeating and does not endure. In aesthetics, as in politics, however, the liberal distrusts tradition, preferring theory. In our enlightened age, it is not enough for a building or artwork to be beautiful, rather it has to satisfy certain theoretical criteria. One only needs eyes to judge how a building looks. It requires an education to understand what a building means.

Only an architectural theorist of Le Corbusier’s brilliance could have built a city as inhuman as Chandigarh. By contrast, the numberless attractive villages that dot the British countryside were built, in the main, by unlettered craftsmen, men who would have found modern architectural theory incomprehensible. The vernacular architectural styles immortalised in Bekonscot evolved across centuries and were to inform the styles of suburban housing into the immediate post-war era.

The latter half of the twentieth century saw the defeat of tradition and the victory of theory, in politics, in art, and in architecture. Just as, for the political utopian, one solution (the common ownership of the means of production, for example, or the disappearance of the state and the triumph of the market) is sufficient to meet the needs of all human societies, so, for Le Corbusier, the principle of ‘form following function’ was a universal maxim. The great brutalist dreamed of a world remade in concrete and glass. Le Corbusier spoke of architecture when he maintained that ‘[In] Oslo, Moscow, Berlin, Paris, Algiers, Port Said, Rio or Buenos Aires, the solution is the same…’ but the sentiment is echoed throughout radical literature.

The Le Corbusiers of the post-war era have left Britain an uglier place. I am confident that, by the time Labour leaves office, many of Britain’s towns will be uglier still.

Britain needs new houses, of course. Would I feel the same sense of trepidation if acres of countryside were to disappear beneath dozens of (full-scale) Bekonscots? No. But, alas, the philistines hold power and are intent on despoiling our countryside with more of the soulless Legolands that litter the outskirts of our towns.

In Bekonscot, of course, it is forever 1933. Were things really better then? Life today is undoubtedly easier, but in many respects, Britain is a less pleasant place in which to live, with the cultural and economic revolutions of the post-war era having eroded social solidarity and trust. This decline finds a strange parallel in the quality of our built environment, as the reins of power passed to those less concerned with ensuring that England looked like England.

Tellingly, overseas visitors to Bekonscot seem to be having a great time. Perhaps Bekonscot looks more like the England they hoped to see than whatever they have found outside.

THE LAST DANCE

This is the future we have chosen, or at least, the future that was chosen for us. We could choose another. Conservatives should reject the mistaken idea that the cultural, social (and yes architectural) changes we are living through are inexorable and unalterable.

Which brings me back to the incident with the Morris dancers.

By the late nineteenth century, Morris was all but dead. A small band of Victorian enthusiasts recognised the tradition’s value and fought to ensure it did not die. Folk dance has never been fashionable, much less ‘useful’ (I should imagine that it would be difficult to convince Angela Rayner of its value) but England would be that little bit poorer if it were to disappear.

Likewise, the antique crafts required to build cottages and cathedrals were passed down across generations and are largely lost now. We are poorer for their being lost. But they could be revived. It only requires will.

Bekonscot’s brochure describes a ‘little piece of history that is forever England.’ There is no reason why the full-size England outside of Bekonscot’s walls should not remain forever England also. Traditions are only truly lost if we stop fighting for them

Photo Credit.