England needs a Second Reformation

It’s over; pack it up, return to Rome or Constantinople, there is literally nothing you can do now. The Church of England General Synod’s has expressed the desire to move away from true doctrine and embrace worldliness.

To a large extent this is nothing new; liberalism within the Church has existed since the latter half of the 20th Century. Many orthodox Anglicans reading this likely disagree with the ordination of women to bishops, let alone as priests; we have had the former for years, and the latter for decades. Those of us still here now did not leave over that – though mind you, many did – so what has changed, really?

Perhaps I am being too dismissive of the problems Anglicans face. After all, the Liturgical Commission (the people who gave us the watered-down liturgy named Common Worship) have revealed they are launching a new project to explore whether our Father should be referred to as such. The Archbishop of York, who I am under the jurisdiction of while I study at the University of Hull, has stated that he will personally conduct blessings for same-sex couples, while the Archbishop of Canterbury has stated he will not – division amongst the church leadership is never a good sign. Those who adhere to orthodox Anglican doctrine, such as myself, face a tough battle.

Not acknowledging small victories would be foolish. The Telegraph reported:

Traditionalists secured a victory by inserting a clause into the approved blessings motion “not to propose any change to the doctrine of marriage”, and “should not be contrary to or indicative of a departure” from this doctrine, that marriage is between a man and a woman.

This foot in the door is crucial, and lumps on more obstacles to changing core church doctrine that the liberals do not have the time to tackle. Indeed, there is a silver lining, which is the focus of this article; a study reported on by the Anglican Journal in 2017 found that churches that hold to orthodox teaching maintain growth, while liberal churches “dwindle away”. This is not merely a phenomenon confined to North America, where the study originates. A recent study from Christian Concern found that most congregations within the Church of England that have the largest attendance by under-16s have conservative views on sexuality. It seems that the future of the Church of England, despite how dire it seems right now, may very well be more orthodox.

Most Anglicans, laity or clergy, are not these nutty w-word communist atheists that many would have you think they are. From my own experience, granted this is not verifiable data, a solid chunk of Anglicans are moderate and often do not hold strong views – but will listen to charismatic and authoritative leaders. On abortion, despite silence on the overturning of Roe vs Wade, the Church of England maintains a rather impressive record for a church so riddled with liberalism – with good rhetoric as recent as 2020. With all of this in mind, what now?

The simple fact is that the universal church of Christ still exists – a ruling by men will not change what our great God teaches. I imagine that the orthodox Anglicans reading this already attend a traditionally-minded church which will not perform same-sex blessings, so not much will change in regards to those parishes that already heed to the Word of God. Furthermore, it is important to consider this; why are we Anglicans in the first place?

I should hope that people have become Anglican because they agree with traditional Anglican doctrine, and that said doctrine is closest, if not exactly, to what Jesus Christ, the Apostles and the Church Fathers taught. Just because the Church of England edges away from Anglican doctrine does not mean that Roman Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy suddenly becomes correct; truth is eternal. We must not make rash decisions – if your local parish church adheres to orthodox doctrine, how would it advance the cause of Anglican orthodoxy to abandon it? Would this not further punish true doctrine when the war is still raging on?

It is easy for those of us with good churches to remain, and it is our duty to remain with them to keep Anglican orthodoxy alive to wait out the deaths of liberal parishes. To wait, though, is not enough; we must be active in activism for true Christian doctrine. Take note of what the church of St Helen’s Bishopsgate and All Souls Church Langham Palace have done as they suspend payments to the liberal Bishop of London. Pursue alternative structures within the Church of England; if your bishop has violated his oath to uphold Christ’s teachings, your church would not be alone if it pursued the system of Alternative Episcopal Oversight to be placed under a bishop who affirms true doctrine, and still remain within the Church of England. Such systems may become very popular soon, with cases of churches rejecting liberal bishops emerging, especially as new traditionalist bishops have been ordained. You as a lay member can help push for this, as I am alongside other laymen (some of whom are converts that I brought into the Church) in my parish church in Hull.

Advocate, push and pursue – on your own if need be, but this should not be so. We are of course called to make disciples of nations, and the best way to spread doctrinal orthodoxy in the Church of England is to convert people yourselves – adding more conservative Anglicans to the flock, solidifying or even changing the doctrine of your parish. Enthusiasm for evangelism is key for growing the Church of Christ on earth, and also preserving that which is true. With all of this, there is still more to do if we are serious as Christians about fixing our beloved Church.

I for one, alongside other Anglicans in Hull, will be pursuing lay ministry to enable us to have the authority to preach and further orthodox Anglican influence within the church. The role itself is not demanding – it is perfectly possible to hold down a job and also be a preacher within the church. Likewise, more important than this is getting elected to the General Synod of the Church of England. After all, it is here where key decisions are made, and it is where we will need to go if we are to win the long-term battle. But who will be our allies?

There are primarily two camps within the Church of England that hold to conservative theology; Anglo-Catholics, most often represented by The Society, and Evangelicals, represented by both the Church Society and the Church of England Evangelical Council (CEEC). Both the Church Society and the CEEC have been consistent in their affirmation of biblical teaching, and their strong opposition to the Bishops’ response to Living in Love and Faith. The Society, on the other hand, seem to be less opposed, with them going so far as to state:

We will study this material carefully when it is published and, in due course, we anticipate issuing pastoral guidance to the clergy who look to us for oversight as to how best these prayers might be used locally.

The lack of a clear rejection of the so-called blessings is stunning, and may upset many orthodox Anglo-Catholics reading this. The simple fact is that it is the conservative evangelicals who are our allies. This may be easier for me to say this, as I am a conservative, reformed evangelical, but we have no time to mourn.

It is time for the Second Reformation to begin, and it will begin with organising opposition to church liberalism. This Reformation, as with the first, must be grounded in the teachings of Jesus Christ, the Apostles and the Church Fathers – and this time with the added help of the Reformers of the 16th Century. Faithful Anglicans, and those who wish to support the Church of England, must rely upon the rock – the true rock upon which the Church is built – that is our faith in Jesus Christ, and the core doctrine of Anglicanism, the Formularies; the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, the Two Books of Homilies and the 1662 Ordinal. We must become more knowledgeable in orthodox Anglican apologetics, and I would strongly recommend the apologetics channel New Kingdom Media for our learning in Anglican doctrine. Stand firm, hold to true Christian doctrine as summarised by the Anglican Formularies, pray and work.

Much like the Reformers of the 16th Century, we face a tough battle. Let us take comfort in the fact that the English Reformers won, despite setbacks from a still quite catholic King Henry VIII and years of oppression under Queen Mary. We have behind us what those who do not follow our great God Jesus Christ do not have; the Grace of God, with which we may work wonders and revitalise Christ’s Church, militant here in England – that once again true Christian doctrine – protestant, reformed and liturgical – may flourish and revive England.

There is work to be done.

The Monarchy isn’t Britain’s Soul

Increasingly pessimistic, this article may very well just be me being unwarrantedly critical. However, there is nothing like a smidgen of conflict to get people interested in reading what we have to say; here goes nothing, I’m going to disagree with Daniel Hawker.

Let me be clear: I am not a republican, nor am I indifferent to the monarchy that we have. I also do not dislike either Edmund Burke or the late Sir Roger, having read works from both – and yet, I disagree with Mr Hawker’s recent commentary piece on the role of our monarchy. The King, or the Royal Family, isn’t ‘Britain’s Soul’, nor is it ‘our one national continuity’ (my emphasis, not Mr Hawker’s). Though, perhaps first I should commend what I think he has gotten right, and where we have common ground.

Our late Sovereign Lady was indeed an embodiment of moral courage and civic duty. I would go so far as to say she was a fantastic public figurehead for traditional, protestant Anglican Christianity. Likewise, it is indeed true that the more radical left want to tear down our traditional institutions, while the soft left want to turn them into glorified green-social democrat mouthpieces – we know. One could even go so far as to say that we should be vocally supportive of our King, or at least the institution of monarchy, perhaps solely on the basis that it annoys the right people.

Britain, however, is not the monarchy; Britain is a nation; a nation is a collective of people. What defines those people is what those people do – the customs and common practices, attitudes and values. The ‘soul’ of the British is our popular culture, or even our values (I would prefer the term religion), in how the British think and so how the British act. British people have generally enjoyed popular sovereignty and familiarity in regards to what is visibly around them. This is why the 2016 Brexit campaign focused on “take back control” and mass immigration changing our familiar towns and cities – against distant institutions on the continent. Nigel Farage did not invoke, at least not prominently, the idea that Brussels had taken power from the Queen.

It is not a good thing that we have a ‘personal connection’ to the Royal Family, or that we view the King as some kind of dad that we never had. It is not ‘trad’ to have the monarch be at the forefront of Britons’ minds; this is counterintuitive to a mystical, sacred monarchy. The word ‘mystical’ is, unsurprisingly, from the same root word as ‘mystery’; secret. How is it possible to maintain mysticism and a sacral quality if the King is supposed to seem intimate to us? How is it possible for the monarchy to be sacred if they appear ordinary? It is this attitude that was the root of the subsequent celebrification of the Royal Family, which has been disastrous. The King does not have to be #relevant to the everyday lives of British people.

There is a necessity in balancing civic involvement, mystical and sacred qualities, and representing public morality – if not a higher morality – that the Royal Family has a duty to pursue. Our King has to remain sufficiently far-off to be sacred. He also has to be visibly moral enough to be respected and involved publicly enough to maintain institutional confidence. Balancing what can be at odds with each other is not easy, but an overly-involved and relevant, though not in the progressive sense, monarchy, which I think, perhaps unconsciously, was guiding Mr Hawker’s thought, is not the right way forward.

If you want to discover and influence “Britain’s Soul”, turn away from institutions and towards the people. Institutions are important, vital even, but they are another subject to what Mr Hawker was trying to tackle. Turn towards what moral, dare I say even religious, forces are guiding everyday people, and what ordinary people do communally. The monarchy did not compel me to love my country, nor does it govern my every action; Jesus Christ does, and I pray in every beloved Book of Common Prayer service that we will only be quietly governed by our monarch. At the end of the day, I do not think that it is historically or presently accurate to pin our whole national being on one institution, albeit an important one, while that which is popular is effectively sidelined.

If you want to discover and influence ‘Britain’s Soul’, be practical, straightforward and actually change how people think and act; how people’s souls are actually oriented. Avoid placing too much emphasis on a single institution, especially when they do not govern our everyday lives. Some institutions ought to, like the Church (which has a presence in every community, I am told), and you may find that they are more relevant to the subject of souls. Other institutions currently hold too much sway over the developing souls of Britons, like schools – as opposed to parents. Other institutions try to suppress the outward signs of inward Graces in our souls, like the police. You will not make any progress in a ‘conservative revolution’ by having tunnel vision.

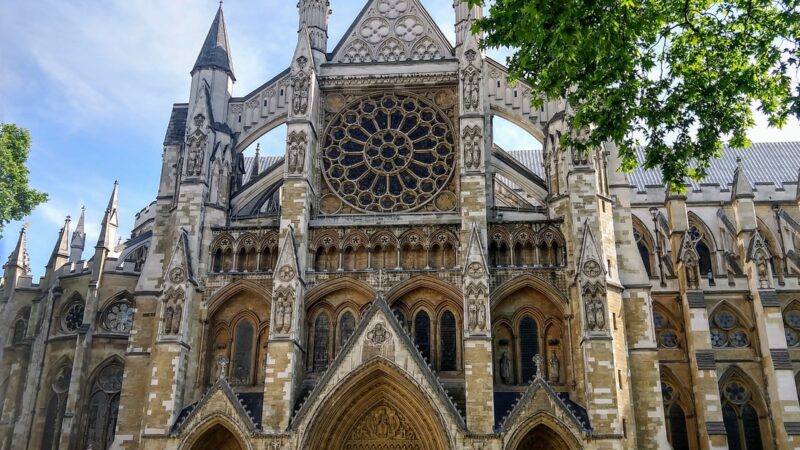

Photo Credit.