Neoconservatism: Mugged by Reality (Part 2)

The Neoconservative Apex: 9/11 and The War on Terror

11th September 2001 was a watershed moment in American history. The destruction of the World Trade Centre by Muslim terrorists, the deaths of thousands of innocent American citizens and the general feeling of chaos and vulnerability was enough to turn even the cuddliest of liberals into bloodthirsty war hawks. People were upset, confused and above all angry and wanted someone to pay for all the destruction and death. To paraphrase Chairman Mao, everything under the heavens was in chaos, for the neoconservatives the situation was excellent.

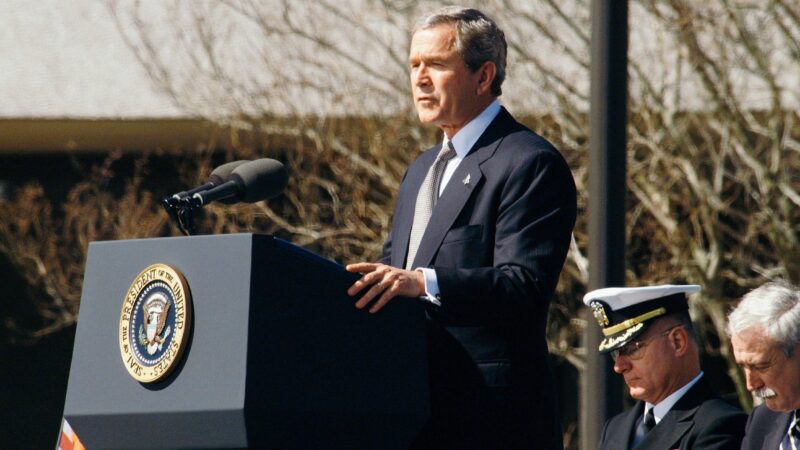

After 9/11, President Bush threw out the positions on foreign policy that he’d advocated for during his candidacy and became a strong advocate of using US military strength to go after its enemies. The ‘Bush Doctrine’ became the staple of US foreign policy during Bush’s time in office and the magnum opus of the neoconservative deep state. The doctrine stated that the United States was entangled in a global war of ideas between Western values on the one hand, and extremism seeking to destroy them on the other. The doctrine turned US foreign policy into a black and white war of ideology where the United States would show leadership in the world by actively seeking out the enemies of the West and also change those countries into becoming like the West. Bush stated in his 2002 State of the Union speech:

“I will not wait on events, while dangers gather. I will not stand by, as peril draws closer and closer. The United States of America will not permit the world’s most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world’s most destructive weapons.”

The ‘Bush Doctrine’ was a pure expression of neoconservatism. But the most crucial part of his speech was when he gave a name to the new war the American state had begun to wage:

“Our war on terror is well begun, but it is only begun. This campaign may not be finished on our watch – yet it must be, and it will be waged on our watch.”

The ‘War on Terror’ became a term that would become synonymous with the Bush years and indeed neoconservatism. For neoconservatives, the attack on 9/11 reaffirmed their pessimism about the world being hostile to the United States and, in turn, their views on needing to eradicate it with ruthless calculation and force. A new doctrine, a new President, a new war – neoconservatism certainly held itself up to its ‘neo’ nature. With all this set-in place and the neoconservative deep state rearing to go, they could finally start to do what they had always wanted to do – wage war.

Iraq and Afghanistan became the main targets, with Al Qaeda, Saddam Hussein and the Taliban becoming public enemy’s number one, two and three. A succession of invasions into both countries, supported by the British military, ended up with the West looking victorious. Both the Taliban and Saddam Hussein had been removed from power, Al Qaeda was on the run, and various of their top leaders had been captured or killed. It was ‘mission accomplished’ and thus time to remould Afghanistan and Iraq into American-aligned liberal democracies. Furthermore, the new neoconservative elite saw to demoralise and outright destroy all those who had been associated with the Hussein regime and Islamic radical groups and thus began a campaign of hunting down, imprisoning and ‘interrogating’ all those involved. However, this is where the neoconservative project would begin to fall as quickly as it had ascended.

The Failure and Eventual Fall of Neoconservatism

A core factor to note is that the neoconservative belief that one could simply invade non-democratic and often heavily religious countries and flip them into liberal democracies proved to be highly utopian. As Professor Ian Shapiro pointed out in his Yale lecture on the Demise of Neoconservatism Dream, the neoconservative’s falsely believed that destroying a country’s military was equivalent to pacifying and ruling a country. The American-British coalition may have swiftly destroyed the armies of Hussein of Iraq and cleared out the Taliban in Afghanistan but they did not effectively destroy the support both had amongst the general population. If anything, the removal of both created an array of intense power vacuums which the neoconservatives could only seem to fill with corrupt American aligned Middle Eastern politicians as well as gun-ho Generals and neoconservative elites who knew very little about the countries they were presiding over.

One such example is Paul Bremer who led the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in Iraq after the Hussein regime was overthrown. His genius idea – that totally would get the Iraqi people on the side of freedom and democracy – was to disband the army and eradicate the Iraqi civil service and governmental authorities of those who were aligned with Hussein’s Ba’ath Party; terming it De-Ba’athification. Both led to a plethora of Iraqi’s losing their jobs and incomes and being smeared as enemies of the new American led regime – even low level teachers and privates were removed despite the fact that many of them joined the party simply to keep their own jobs.

While seen as a tactical way in which to remove any potential opposition to the CPA, the move created more opposition to the new government than any dissident anti-American group could have wished to have created – turns out making 400,000 young men, who know how to kill a man in sixteen different ways, unemployed isn’t the best way in which to show your care for the Iraqi people. It also didn’t help that Bremer and the CPA failed to account for a variety of funds and financial given to him for the reconstruction of Iraq, leading to a variety of financial blackholes and millions of dollars that simply disappeared.

Insurgent groups grew and assassination attempts on Bremer became commonplace to such an extent that even Osama Bin Laden himself placed a sizable bounty on Bremer’s head. Opposition to Bremer was so fervent that he was essentially forced to leave his position in the CPA by mid-2004 with his legacy being one of failure, instability and corruption, a legacy which the Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich called “the largest single disaster in American foreign policy in modern times”.

Removing opposition instead of attempting to work with it and use their expertise is something the US has done before, especially after WW2 with the fall of the Axis regimes, but the neoconservative mind has no tolerance or time for those who oppose American values – leading to brutal methods being used against those who do not comply.

It was under the neoconservatives that Guantanamo Bay was opened, a prison known for its mistreatment of prisoners and dubious torture methods. It was under the neoconservatives that Abu Ghraib prison, a feared prison under Hussein’s regime, became a place in which American soldiers and state officials were allowed treat and use interrogation methods on prisoners in manners that violate basic human dignity. And it was under the neoconservatives that began a mass surveillance state in their own country via the so-called ‘Patriot Act’ which put the privacy of American citizens in great danger. The Bush administration claimed that these abuses of human rights were not indicative of US policy, they were and the neoconservatives were the one’s responsible.

Luckily, these abuses were quickly all over mainstream news both inside and outside the US and horrified the population at large, even those who had once been pro the War on Terror. Furthermore, soldiers who had fought abroad came back with horror stories of their fellow soldiers abusing prison inmates and how they’d left Iraq bombed to the ground, displacing families and with casualty rates of up to and around 600,000 Iraqi civilians. The American mood turned against the war and by the end of Bush’s tenure in office 64% of Americans felt that the Iraq war had not been worth fighting.

The average American who felt angry and upset at their freedoms being threatened by Islamic terrorism became just as angry and upset when they saw their own country committing atrocities and taking away the freedoms of others. While it may seem cliche to point out the hypocrisy, this was one of the first times American’s had been exposed to the reality of what their state was really capable of. As Shapiro elucidates, the real legacy of the Iraq war and the War on Terror is that it destroyed America’s moral high ground. A high ground America has never been able to reach to since.

Barrack Obama and the Democrats attacked the Republicans and their neoconservative wing for their human rights abuses, the unjustified invasion of Iraq and implosion of America’s moral standing on the international stage. It is not unfair to say that Obama’s intoxicating charm and message of hope for America was desperately wanted in a post-Bush era in order so that Americans could try and forget the depravities that their country had fallen to in the early 2000s. He promised to pull out of Iraq, close Guantanamo Bay and replace the neoconservative doctrine for one based on diplomacy and moderation.

Bush and the majority of his neoconservatives left office after the election of Obama – in which he beat the then darling of the neoconservative right John McCain – and have since failed to re-enter the halls of power or indeed even their own party. The Tea Party movement supplanted neoconservatism dominance over the Republican Party and those still clinging on for dear life are being cleared out by the new America First aligned Republicans who wish to supplant the war-hawks and globalists with non-interventionists and nationalists.

Conclusions

It is not radical nor unfair to say that not since the fall of the Berlin Wall has an ideological group lost its grip on power so completely as the neoconservatives have.

With the failure of nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan, the grotesque violation of individual liberties at home and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, neoconservatism, and indeed even the US government, became synonymous with warmongering, authoritarianism and out and out international crime. To quote Stephen Eric Bronner in his book Blood in the Sand:

“Like a spoiled child, unconcerned with what anyone else thinks, the United States has gotten into the habit of invading a nation, trashing it, and then leaving without cleaning up the mess.”

Neoconservatives like to hand-wring about the ‘evils’ of Middle Eastern dictators while they allow dogs to tear off the limbs of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, spy on innocent American citizens and bomb Afghani schools full of children into oblivion. Thanks to the neoconservative project of the early to mid-2000s – elements of which still are in place today – the United States became a leviathan monstrosity of surveillance, torture, corruption and warmongering.

It is interesting to see that after being the “cause célèbre of international politics”, neoconservatives are now the frequent targets of ridicule and scorn. And deservedly so, especially considering what neoconservatism has devolved into. The Straussian and genuinely conservative elements of the political philosophy have been ripped out, replaced with vague appeals to liberal humanitarianism and cucking for globalist organisations like the UN and NATO. The caricature of neoconservatives wanting drag queens to be able to use gender-neutral bathrooms at McDonalds in Kabul has shown to be somewhat accurate. After all, neoconservatives exist to promote ‘Western values’ in foreign countries, so naturally what they will end up promoting is the current cultural orthodoxy of progressive leftism, intersectionality and social decadence. An orthodoxy I’m sure Middle Easterners are desperately clamouring for.

However, despite their dwindling ranks and watering down of the ideology, the essence of neoconservative foreign policy remains intact; they still think the world should look like the United States. Therefore, it is unsurprising to see neoconservatives calling for every country in the world to be a liberal democracy along with the American model, or for Western troops to stay in Afghanistan indefinitely. Not only are these convictions still deeply held but are a direct expression of wanting American global hegemony to persist. On a deeper level, the recent pearl-clutching and whining from neoconservatives about the whole ordeal is simply a reflection of the anxiety that they now hold. Their ideas about what the world should look like have come collapsing before their eyes. And they can’t bear to face the fact that they were wrong.

This collapse has been occurring for some time and hopefully with the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, and the recent moves amongst elements of the right and left to adopt a more non-interventionist approach to foreign policy, the collapse of neoconservatism will remain permanent. After all, the neoconservatives who backed President Joe Biden – thinking he would spell a revival in their views – have now had an egg thrown in their face. Biden has proven himself to not be aligned with neoconservative foreign policy views.

Despite his claims that ‘America was back’ and his past support of foreign interventionism, it is evident that Biden has no real ideological attachment to staying in Afghanistan. In turn, he seems to have found it relatively easy to pull out and then spout rhetoric that wouldn’t be uncommon to hear at a Ron Paul rally. He stood against nation-building, turning Afghanistan into a unified centralised democracy and rejected endless military deployments and wars as the main tool of US foreign policy. Biden, alongside President Donald Trump, has turned the tide of US foreign policy away from military interventionism and back towards diplomacy. A surprise to be sure, but a welcome one.

However, while the ‘War on Terror’ may firmly be at an end – the American state has worryingly turned its eyes towards a new ‘War on Domestic Terror’. A war that political scientist and terrorism expert Max Abrahams worries will be catastrophic for the United States, quoting Abrahams:

“The War on Terror destabilized regions abroad. It’ll destabilise our country all the same… We cannot crack down on people just because we don’t like their ideology…otherwise the government is going to turn into the thought police and that is going to spawn the next generation of terrorists.”

The neoconservatives may have lost the war on terror but the structures and policies they put in place to fight that war are now being used, and being used more effectively, against so-called ‘domestic terrorists’. The American regime’s tremble in the lip is so great that it now believes the real threat to its existence lies at home. While this ‘War on Domestic Terror’ is still in its early stages, it is clear that the neoconservative deep state’s toys of torture, mass surveillance and war are now being put to other uses. Only time will tell if it will have the same consequences in America as it did in the countries it once occupied.

.

With the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan and Iraq; the continued rise of anti-interventionism on the right and left; and the memory of the failure of conflicts in the Middle East fresh in people’s memories, neoconservatism has been all but relegated to the ideological graveyard – its body left rot under the cold soil for eternity. A fitting fate.

“A neoconservative is a liberal who has been mugged by reality” proclaimed the godfather of the ideology. But in the perusal of utopian imperial ambitions it has now suffered the same fate – neoconservatism has been mugged by reality. A reality it so desperately and violently tried to bring to heel.

Time To Stop Being Conservatives

‘Conservative’, big and small ‘c’, is blah. Blah party, policies, politicians, polls, prospects, and that’s just the ‘p’ words.

Let’s deal with ‘party’ first. Perhaps you’ve already stopped being a Conservative. There’s plenty of debate among the duckies about leaving, destroying, destroying and rebuilding, long marching through, etc. the Conservative Party. Whatever, sure, broadly, one way or another, there should be a proper political force which reflects ducky views. More on this later.

The real question is this: should you even be a conservative, let alone a Conservative, any more? What is the virtue of being a ‘conservative’? It’s a small tactical mistake, with large consequences, but easily tweaked and fixed. The Conservative Party may present itself as conservative and full of people who are not. How has that worked out?

Policies. What on a practical political level has ‘being a (C/c)onservative’ got you for the last decade, or more? What is it getting you now? What does it look like it’s going to get you in the next decade…or more?

Politicians. Ultimately, it’s these guys to blame for the blah policies. It shouldn’t be any surprise that the Conservative Party has blah policies though. Just look at its politicians. I’ve written at length (see the May 2022 magazine) about how, basically, the Conservative Party doesn’t select for competence, it selects for loyalty, and how changing its composition is unrealistic. You’re just going to have to be stuck with a ministerial cadre which belly flops, marries pensioners, plays hide and seek, and gobbles knobs for public entertainment. Is it even accurate to say that these people present as ‘conservative’ while failing to govern as conservatives? In any case, why are you surprised that they’re failures, and why would you care to keep associating with them? It’s time to stop being conservatives.

Polls. When the presentation of ‘conservative’ is so beyond saving, all that’s left is the reverse. Be conservative, act conservative, but don’t care to present as a conservative. Keep all the principles, attract the people who have them, those who like to pretend they don’t because it’s not fashionable, and those who are merely superficially put off. It costs you nothing but, what, comfiness, pride, what? To ditch a label which gets you nothing practically or aesthetically?

Jake Scott is right. Conservatives aren’t cool. Isn’t it incredibly telling that I’m by far the coolest person he knows and I’m not a conservative? It’s why I’m telling you not to be too. It’s not just the young fogeys, Thatcher throbbers, port & policy chortlers, MP-selfie-profile-pictures – does that cover it? – it’s the concept itself.

Prospects. Alright, this is a bit flimsy, and I’m done with this ‘p’ gimmick. ‘Conservative’ keep you trapped in a progressive paradigm, limiting your prospects. You are conservative relative to their progress. Sure, they’re progressive relative to what you want to conserve, but is that really how it’s taken in the zeitgeist? It doesn’t work the other way around. ‘Conservative’ doesn’t sound like you want to keep what’s what. It sounds like there’s one of two broad choices you can be, left/right, Conservative/Labour. What is it to present as the ones who just want to stick where you are and do nothing? “But there’s plenty I want to build and fix and do to make the UK excellent”, you say. Good! I hear you. In fact, a line from The Mallard’s own Wednesday Addams in her review of Peter Hitchens’ new book stood out to me. “He mourns not for a pristine past, but a future that never was”. Does the word, name, presentation, etc. of ‘(C/c)onservative’ ever connote that idea too? Would anyone associate the word or concept of the future with ‘(C/c)onservatives’ on Family Fortune? Whatever, this is a small tweak too.

Don’t just mourn, don’t be one of those people who seem to enjoy self-pity, wallowing in the ‘man among the ruins’ thing. Even if it’s not so negative, don’t just be twee, oh the green and pleasant land, God save the King, blah. Find and keep what’s valuable, think about how to conserve it, but also how to bring it into the future. While you’re at it, adjust your attitude toward the future. Hitchens is an old man, so whatever, maybe it’s forgivable that all he can do is mourn for a future that never was. But you can act for a future that will be. It will. And you have to totally unironically, unreservedly believe that. Make it a matter of truth!

Jake Scott is right again. Stop pretending as if you are living in a liberal pluralist society in which different ideologies are just different options in a marketplace. I’m not sure this is quite what he meant, but it’s my take: some ways of doing things are better than others. Whether that’s economic, educational, social, whatever. There are better and worse ways of running a country. The progressives are objectively shit.

Truth. You are not a conservative, you are not right wing, even, you just believe in the truth. Twitter has been in the news, let’s use that as an example. The now dismal, disgraced, and now discarded Vijaya Gadde, could not even begin to conceive that Twitter had biased rules against conservatives on defining ‘misgendering’. It’s because her opinion wasn’t just an opinion. It was the truth. Of course, she was wrong. You are the ones with the truth. This is going to get tiresome referring to the same Jake Scott video, but he is right again. If anything he isn’t radical enough. On some things there just is no battle of ideas. There is no debate on insanity. Not in the real world, at least, maybe stuffed away in university philosophy departments where the debate can keep going for 3,000 years without resolution and not interfere with anything that matters.

Anyway, the truth is also that broadly conservative ideas about a whole range of topics are held by most of the country. Brexit was the big one, already proven. Next could be anything from immigration to British values, house building, tax, or all of them if only there was a proper political force prepared to go for it. More on that right at the end. In the meantime, what you believe is true and it will come to be, because you are going to make it happen.

This article hasn’t come out of nowhere, exactly. There does seem to be some buzz around the idea of ‘sensible centrists’. Is that the right branding? Not sure about it, but the concept is onto something which is good politics.

TL;DW, examples from the linked video: 1) it’s extreme to import hundreds of thousands of people to the country, the sensible position is to set immigration by what the country needs, 2) it’s extreme to let crime go rampant and obsess over the relatively small problem of one or two racist police, the sensible position is to be tough on crime, or 3) it’s extreme to hire thousands of people to obsess over a small number of people getting offended, to the tune of billions, rather than just not cater to that hysterical timewasting minority.

It’s not an entirely new idea, but popularising it in ‘right-wing’ circles is valuable, and so is the formula, which is new. The proof that it’s good is that it has been done before. How far back do you want to go? Curtis Yarvin presents Caesar as an imperially purple (red/blue/Republican/Democrat) end to chaotic fighting between extremes – a sensible centre. More recently Vote Leave presented the ‘leave’ option as a sensible left and right-backed, cross-party, non-UKIP, sensible centre which was merely taking back control from an extreme EU, where actually remaining would be the less certain, more dangerous, crazy option.

Does the UK feel stable, well-governed, on the right and true path, today? Is the UK sensible or extreme? See the appendix below if you need any help. Everything is totally fucking awful. It doesn’t even have to be! It could just be well governed instead. You’re not a conservative, you just want a good government.

Today, it is governed by Conservatives. It has been backed by conservatives or otherwise simply just not replaced by conservatives, and in any case conservatives have been totally contaminated by the idea of Conservatives. On top of all of this, when you have the truth on your side, what is there even to be gained by being (C/c)onservatives? Again, see the appendix below for some sense of the scale of the problem.

I’m not sure what exactly is next. Rallying around any sort of name or group or identity, especially if it isn’t totally solid and ready, presents a target. For now it’s enough to simply reject the idea that you are a conservative, or right-wing, especially when asked or characterised as such.

Photo Credit.