A Premise:

Deep, and yet deeper down, below the marsh slime and the swamp rot, even underneath poppy roots and the granite rows, Old England’s Foundations lie. While thinned and turned soils are cold and damp, the fiery Mantle warms and pulses, twisting round and circling on itself; the Core sees into itself and ponders on its shadows; to reach out into the cold and dark, hope perchance to find new wheels to turn, or perhaps not. Content, in the underworld, dreaming of the pictures of its marble face, Old England’s Foundations are buried the deepest, overwritten by thin and beaten sheets of plaster and tissue paper.

Yet, this is a fantasy: circumstantial myths of Old England, and its Foundations. Those marshes were sealed, and the swamps became roads, and the shapes and the names of the trees do not matter anymore. Accumulated plays turned in on themselves and became a meaningless fresco; the hand-me-down uniform, hoarded in poverty, with no weavers to craft anew. That Core is no form but a feeling, fleeting and shallow, giving only the image of warmth. Gawp at the statues and the towers and the gold on the wall. They were never yours.

Intermission, The Alchemists’ Folly:

Higher, and yet higher so, far reaching beyond the sea and above the clouds, up and up Nature’s Ladder, climbs a Champion. For all its power and glory. He soon received the ravenous attention of The Crow, the most cunning of all the birds. It said: “I have seen many climb, and their plans dissolved away, but wear my feather, and sing my song, and Nature’s sure to play”. The Crow put a feather on The Champion’s shoulder, and The Champion cawed until he had near reached the clouds. He looked down to measure his climb, and one cheek was slashed by The Crow’s feather; he saw many other smaller birds with more beautiful sounds and colours than The Crow, hiding fearfully away in their nests.

Higher and higher, between the feathers and the stars, up The Ladder, climbed The Champion. The clouds from below were sunlit pillars in the sky yet seemed smoke and fog inside. At once, the guiding stars were blotted out, and The Champion was frozen in the dark. He begged it clear, and The Cloud said: “Truly, Nature loves to hide, and seems at first a chaos sight, but learn its ways, obey and pay, by water’s path will light”. The Champion’s waterskin was plucked by a gale, and The Cloud gave in credit due a magic hailstone, and it magnified the light of the stars. His fingers were cold and heavy, his water was lost, and the constellations seemed more twisted than ever before; but, with the dim path seen by magic divined, The Champion waged on.

An earthquake struck, and The Ladder path fell; weathered wood, by many footsteps heeled, shattered with the turning of a generation. His bearing steers all amiss under the dizzying constellations, for the old way is no more; and The Champion loses their footing, curses the folly, and plummets into brine under the bottommost rungs; championing, no more. The Fool who works with wood and nail, at the bottom of The Ladder, did not build houses that day, for another ladder was built by him; and The Fool then propped it, already to seize the opportunity, to climb the path again. But The Cloud and The Crow remain in their Nature, as they wait between the salt and the stars.

Their Conclusion:

Hailing practice and ritual, making nothing new, and the new, ugly; what comes from a fool’s history? Yesterday’s legislation becomes today’s tradition, and old and common habits are preserved by kitsch committee. To justify what happened, because it happened, accounting to stacked sediments of past scoresheets? If that is good, then good is evil; bored eyes make nothing beautiful around our empty hands, so we make eternities of nothing, and are compassed about by our enduring appetites. With Nature as your sentimental measure, you pay tribute to accidental shadows on the wall. Where is The True, The Good, The Beautiful? God have mercy on your windswept souls.

You Might also like

-

Orwell’s Egalitarian Problem

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is a book whose influence exceeds its readership. It resembles a Rorschach test; moulding itself to the political prejudices of whoever reads it. It also has a depth which often goes unnoticed by those fond of quoting it.

The problem isn’t that people cite Orwell, but that people cite Orwell in a facile and cliched manner. The society of Oceania which Orwell creates isn’t exemplified in any contemporary state, save perhaps wretched dictatorships like North Korea or Uzbekistan. It’s thus not my intent to draw on Nineteen Eighty-Four to indict my own society as being “Orwellian” in the sense of being a police state, a procurer of terror, or engaged in centralised fabrication of history. A world of complete totalitarianism of the Hitlerian or Stalinist kind hasn’t arrived (not yet at least), but Nineteen Eighty-Four still has insights applicable to our day.In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the protagonist, Winston, is suffocated by the miserable tyranny he lives in. The English Socialist Party (INGSOC) controls all aspects of Britain, now called Airstrip One, a province of the state of Oceania. It does so in the name of their personified yet never seen dictator, Big Brother. When Winston is almost at breaking point, he meets fellow party member, O’Brien. O’Brien, Winston thinks, is secretly a member of the resistance, a group opposing Big Brother. O’Brien hands Winston a book called The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism. This book is supposedly written by Emmanuel Goldstein, arch-nemesis of Big Brother, and details the secret history and workings of Oceanian society, something unknown to all its citizens.

Oligarchic collectivism is the book’s term for the ideology of the Party in response to a repeating historical situation. Previous societies were characterised by constant strife between three social classes: the top, the middle, and the bottom. The pattern of revolution across history was always the middle enlisting the bottom by pandering to their base grievances. The middle would use the bottom to overthrow the top, install itself as the new top, and push the bottom back down to their previous place. A new middle would form over time, and the process would repeat.

INGSOC overthrew the top through a revolution, in the name of equality. What it actually achieved was collectivised ownership at the top, and so it created a communism of the few, not unlike classical Sparta. The rest of the population, derogatorily called “proles”, live in squalid poverty and are despised as animals. They’re kept from rebelling by being maintained in ignorance and given cheap hedonistic entertainment at the Party’s expense. INGSOC nominally rules on their behalf, but in reality is built upon their continual oppression. As Goldstein’s book puts it:

“All past oligarchies have fallen from power either because they ossified or because they grew soft. Either they became stupid and arrogant, failed to adjust themselves to changing circumstances, and were overthrown; or they became liberal and cowardly, made concessions when they should have used force, and once again were overthrown. They fell, that is to say, either through consciousness or through unconsciousness.”

In other words, the top falls either by failing to notice reality and being overthrown once reality crashes against it, or by noticing reality, trying to create a compromise solution, and being overthrown by the middle once they reveal their weakness. INGSOC, however, lasts indefinitely because it has discovered something previous oligarchies didn’t know:

“It is the achievement of the Party to have produced a system of thought in which both conditions can exist simultaneously. And upon no other intellectual basis could the dominion of the Party be made permanent. If one is to rule, and to continue ruling, one must be able to dislocate the sense of reality. For the secret of rulership is to combine a belief in one’s own infallibility with the Power to learn from past mistakes.”

INGSOC can simultaneously view itself as perfect, and effectively critique itself to respond to changing circumstances. It can do this, we are immediately told, through the principle of doublethink: holding two contradictory thoughts at once and believing them both:

“In our society, those who have the best knowledge of what is happening are also those who are furthest from seeing the world as it is. In general, the greater the understanding, the greater the delusion; the more intelligent, the less sane.”

It’s through this mechanism that the Party remains indefinitely in power. It has frozen history because it can notice gaps between its own ideology and reality, yet simultaneously deny to itself that these gaps exist. It can thus move to plug holes while retaining absolute confidence in itself.

At the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Inner Party member O’Brien tortures Winston, and reveals to him the Party’s true vision of itself:

“We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means, it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship. The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power. Now do you begin to understand me?”

It’s here where I part ways with Orwell. For a moment, O’Brien has revealed to Winston one-half of what Inner Party members think. Doublethink is the simultaneous belief in the Party’s ideology, English Socialism, and in the reality of power for its own sake. INGSOC is simultaneously socialist and despises socialism. Returning to Goldstein’s book:

“Thus, the Party rejects and vilifies every principle for which the Socialist movement originally stood, and it chooses to do this in the name of Socialism. It preaches a contempt for the working class unexampled for centuries past, and it dresses its members in a uniform which was at one time peculiar to manual workers and was adopted for that reason.”

Orwell creates this situation because, as a democratic socialist, he’s committed to the idea of modern progress. The ideal of equality of outcome isn’t bad, but only the betrayal of this ideal. Orwell critiques the totalitarian direction that the socialist Soviet Union took, but he doesn’t connect this to egalitarian principles themselves (the wish to entirely level society). He therefore doesn’t realise that egalitarianism, when it reaches power, is itself a form of doublethink.

To see how this can be we must introduce an idea alien to Orwell and to egalitarianism but standard in pre-modern political philosophy: whichever way you shake society, a group will always end up at the top of the pile. Nature produces humans each with different skills and varying degrees of intelligence. In each field, be it farming, trade or politics, some individuals will rise, and others won’t.

The French traditionalist-conservative philosopher Joseph de Maistre sums up the thought nicely in his work Etude sur La Souveraineté: “No human association can exist without domination of some kind”. Furthermore, “In all times and all places the aristocracy commands. Whatever form one gives to governments, birth and riches always place themselves in first rank”.

For de Maistre the hard truth is, “pure democracy does not exist”. Indeed, it’s under egalitarian conditions that an elite can exercise its power the most ruthlessly. For where a constitution makes all citizens equal, there won’t be any provision for controlling the ruling group (since its existence isn’t admitted). Thus, Rome’s patricians were at their most predatory against the common people during the Republic, while the later patricians were restrained by the emperors, such that their oppression had a more limited, localised effect.If we assume this, then the elite of any society that believes in equality of outcome must become delusional. They must think, despite their greater wealth, intelligence and authority, that they’re no different to any other citizen. Any evidence that humans are still pooling in the same hierarchical groups as before must be denied or rationalised away.

This leads us back to the situation sketched in Goldstein’s book. What prevents the Party from being overthrown is doublethink. The fact it can remain utterly confident in its own power, and still be self-critical enough to adapt to circumstances. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the former is exemplified in the vague utopian ideology of INGSOC, while the latter is the cynical belief in power for its own sake and willingness to do anything to retain it. But against this, no cynical Machiavellianism is necessary to form one-half of doublethink. A utopian egalitarian with privilege is doublethink by default. At once, he believes in the infallibility of his ideology (he must if he’s to remain in it), and is aware of his own status, continually acting as one must when in a privileged position.

How does this connect to that most Orwellian scenario, the permanent hardening in place of an oligarchic caste that can’t be removed? As Orwell says through Goldstein, ruling classes fall either by ossifying to the point they fail to react to change, or by becoming self-critical, trying to reform themselves, and exposing themselves to their enemies. Preventing both requires doublethink: knowing full well that one’s ideology is flawed enough to adapt practically to circumstances and believing in its infallibility. The egalitarian elite with a utopian vision has both covered. If you truly, genuinely, believe that you’re like everyone else (which you must if you think your egalitarian project has succeeded), you won’t question the perks and privileges you have, since you think everybody has them. That takes care of trying to reform things: you don’t.

Yet, as an elite, you still behave like an elite and take the necessary precautions. You avoid going through rough areas, you pick only the best schools for your offspring, and you buy only the best houses. As an elite, you also strive to pass on your ideology and way of life to the next generation, thus replicating your group indefinitely. Thus, you simultaneously defend your position and believe in your own infallibility.Could an Oceanian-style oligarchy emerge from this process? Absolutely, provided we qualify our meaning. The society of Nineteen Eighty-Four lacks any laws or representational politics. It has no universal standards of education or healthcare. It functions as what Aristotle in Politics calls a lawless oligarchy, with the addition of total surveillance. But this is an extreme. What I propose is that egalitarianism, once in power, necessarily causes a detachment between ideology and reality that, if left to itself, can degenerate into extreme oligarchy. The severe doublethink needed to sustain both belief in the success of the project and safeguard one’s position at the top can accumulate over time into true class apartheid. This is, after all, exactly what happened to the Soviet Union. As the Soviet dissident and critic Milovan Dilas, in his book The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System, put it:

“Every private capitalist or feudal lord was conscious of the fact that he belonged to a special discernible social category. (…) A Communist member of the new class also believes that, without his part, society would regress and founder. But he is not conscious of the fact that he belongs to a new ownership class, for he does not consider himself an owner and does not take into account the special privileges he enjoys. He thinks that he belongs to a group with prescribed ideas, aims, attitudes and roles. That is all he sees.”

To get an Oceanian scenario, you don’t need egalitarianism plus a Machiavellian will to power, forming two halves of doublethink. You just need egalitarianism.

Post Views: 1,091 -

Economic Bondage Against the Family (Magazine Excerpt)

In his 1936 Essay on the Restoration of Property, the author Hilaire Belloc recalls an image he had read two decades before and reproduces to the best of his memory. I’ll adapt it: imagine a single machine that produces everything society could possibly need. If this machine is owned by the collective, through a caste of bureaucrats, we have socialism. Everyone who tends the machine are regularly doled-out what they allegedly need by this bureaucratic caste. If the machine is owned not by many but by just one man, we have monopolistic capitalism, of the type resulting from complete laissez-faire. Most people work the machine and get a wage in return so they can buy its produce. Some others are employed in entertaining the owner, and all the rest are unemployed.

Belloc doesn’t say it, but we could imagine that working the machine involves just pushing a button repetitively. If technology did advance to the point that all which humans need could be provided by one machine, surely it could be worked by merely pushing one button repeatedly.

I rehearse this second-hand image because through it Belloc makes a point: these are capitalism and socialism as “ideally perfect” to themselves. If such a machine existed, this is what each system would look like.

Both monopoly capitalism and socialism share an agnosticism about the role of property and work in human life. Neither ideology views work nor property as ends in themselves but only means to further ends. For the socialist this end is consumption. Material needs are more important than freedom. To borrow again an image from Belloc, socialists view society as like a group stranded on a raft. The single overwhelming concern is not starving, so food is rationed and handed out according to a central plan. Perhaps a man finds fishing fulfilling and would lead a happy life honing the fishing craft. Maybe he would benefit from selling fish for a profit so he can support his craft. But the circumstances are extreme, so the group take collective ownership of his fishing rod and collective charge of distributing the fish. It’s for this reason that socialism is so appealing to ideologies that see existence as struggle.

For the monopolist this end is profit. Money-making is the only purpose of economic activity, separate from any human need or fulfilment from work. Property is good only if it generates money; not because it has any fixed purpose within human life. Work also is good only if it generates money, and if profits can be increased while reducing the amount of work needed, this is preferable. This is the reasoning Adam Smith uses to create the production line. The goods produced, further, also have no value apart from the profit they create.

Neither system recognises that humans are rational animals who flourish by both having and using private property as an extension of their intelligence. Thus, if a machine existed which could produce everything needed for life by repeatedly pushing a button, both systems would adopt it and consider themselves having achieved perfection. Everybody (or almost everybody) could be employed doing the same repetitive activity, differing only on the matter of whether their employer is private enterprise or the collective.

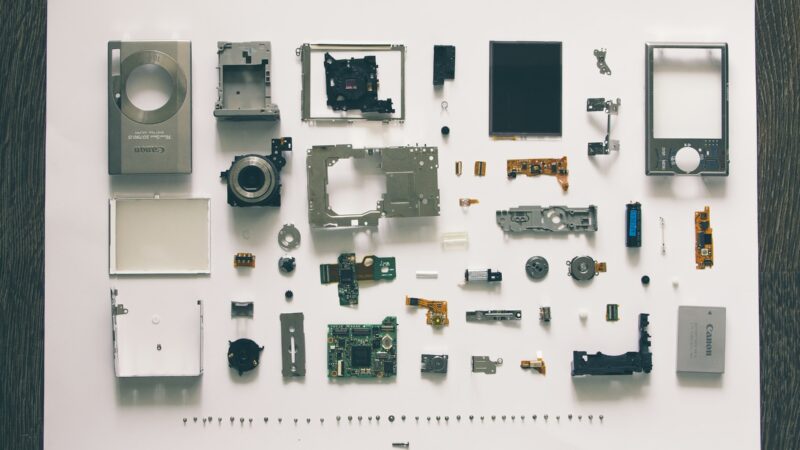

The worker pushing a button is akin to one working on a conveyor belt in a factory, or in bureaucratic pen-pushing. His livelihood consists in a single repetitive and mindless task which requires little intelligence to perform. A craftsman, on the other hand, creates something from start to finish by himself or as part of a team effort with other craftsmen. Intelligence runs all through the activity. Making a teapot, fixing a car engine, building a house, or ploughing a field, each requires applying a design with one’s hands, that has already been worked-out by one’s mind.

Another effect of this agnosticism involves the consumer. The sort of consumption monopolists think about is a limitless glut happening in a social vacuum. It is want unrelated to need, because the only way we can truly specify need is by defining a fixed purpose for human life. Human needs, on an ancient view, relate to the kind of life humans must live to be truly happy and flourishing. So, we need food, water, shelter, and other commodities. But we also need to exercise our uniquely human faculties, like creativity, aesthetic appreciation, imagination and understanding. We also need to know how much of a good or activity to have. After all, eating until we pass out isn’t good for us, and to sit around imagining all day may run into idleness.

As a result, neither system has much room for organic human community at the local level. Such communities depend on need which goes beyond the mere satisfaction of material wants. Work, for example, is more than just a way to get what we need to live. It’s a vocation, which taps into our rational human nature, and gives us joy through creating and shaping our surroundings.

This is an excerpt from “Nuclear”.

To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

Post Views: 749 -

Liberalism and Planned Obsolescence

Virtually everyone at some point has complained about how their supposedly state-of-the-art phone, tablet, laptop, or computer doesn’t seem quite so cutting-edge when it either refuses to work properly or ceases to function entirely after a disappointingly brief period of time. This is not merely the grumblings of aggravated customers, but a consequence of “planned obsolescence.” The term dates back to the Great Depression, coined by Bernard London in his 1932 paper Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence, but a practically concise definition comes courtesy of Jeremy Bulow as “the production of goods with uneconomically short useful lives so that customers will have to make repeat purchases.” Despite being an acknowledged (and in some cases encouraged) practice, it is still condemned; both Apple and Samsung have faced legal action on multiple occasions for introducing software updates which actively hinder the performance of older devices. In the face of all this, planned obsolescence isn’t going anywhere so long as there is technology, nor does anyone expect it to. It is, as death and taxes are, one of the few certainties of life.

As the title of this essay suggests, I do not intend to delve any further into the technological or economic ethics of planned obsolescence. Interesting as they may be, I want to focus on how the concept appears in a political context; more specifically, in liberalism.

One of the core tenets of liberalism is a belief in the “Whig interpretation of history.” In his critique of the approach, aptly titled The Whig Interpretation of History, Herbert Butterfield outlined the Whig disposition as being liable to “praise revolutions provided they have been successful, to emphasize certain principles of progress in the past and to produce a story which is the ratification if not the glorification of the present.” To boil it down, it is the belief that history is a continuous march of progress, with each successive step freer and more enlightened than the last. A Whiggish liberal is dangerously optimistic in their opinion that history has led to the present being the greatest social, economic, and political circumstances one could hitherto be born into. More dangerous still is their restlessness, for as good as the present may be, it cannot rest on its laurels and must make haste in progressing even further such that the future will be even better. The pinnacle of human development lasts as long as a microwave cooking a spoon, receiving for its valiant effort little other than sparks, fire, and irreparable damage resulting in its subsequent replacement.

The unrepentant Whiggery of the modern world has prompted scholars of the Traditionalist School of philosophy to label it an aberration amongst all other societies, as the first which does not assign any inherent value to, or more accurately, openly detests, perennial wisdom (timeless knowledge passed down through generations) and abstract metaphysical truths. In the words of René Guénon, “the most conspicuous feature of the modern period [is its] need for ceaseless agitation, for unending change, and for ever-increasing speed.” Quite literally, nothing is sacred. One of the primary causes of this is that modernity, defined by its liberalism, is materialist, and believes that anything and everything can and should be explained rationally and scientifically within the physical world. The immaterial and the spiritual are disregarded as irrational, outmoded and unjustifiable; it is, as Max Weber says, “disenchanted.”

To understand this further, we must consider Plato’s conceptions of the two distinct natures of the spiritual and the material/physical world, “being” and “becoming” respectively. Being is constant and axiomatic, characterised by abstract ideas, timeless truths and stability. Becoming on the other hand, as the nature of the physical world, reflects the malleability of its inhabitants and exists in an endless state of flux. Consider your first car, it will alter with time, the bodywork might rust and you may need new parts for it, and indeed it may eventually be handed on to a new owner or even scrapped entirely. Regardless of what changes physically, its first car status can never be separated from it, not even when you no longer own it or it’s recycled into a fridge, for it will always hold a metaphysical character on a plane beyond the material.

Julius Evola, another Traditionalist scholar, succinctly defined a Traditional society as one where the “inferior realm” of becoming is subservient to the “superior realm” of being, such that the inherent instability of the former is tempered by orientation to a higher spiritual purpose through deference to the latter. A society of liberalism is unsurprisingly not Traditional, lacking any interest in the principles of being, and is instead an unconstrained force of pure becoming. Perhaps rather than disinterest, we can more accurately characterise the liberal disposition towards being as hostile. After all, it constitutes the “customs” which one of classical liberalism’s greatest philosophers, John Stuart Mill, regarded as “despotic” and a “hindrance to human development.” Anything which is perennial, traditional, or spiritual is deleterious to the march of progress unless it can either justify its existence within the narrow rubric of liberal rationalism, or abandon its traditional reference points and serve new masters. With this mindset, your first car doesn’t represent anything to do with the sense of both liberation and responsibility that comes with being able to transport yourself, it is simply a lump of metal to tide you over until you can get a more expensive lump of metal.

Of course, I do not advocate keeping a car until it falls to pieces, it is simply a metaphor for considering the abstract significance of things which may be obscured by their physical characteristics. In the real world, the stakes are much higher, where we aren’t just talking about old cars but long-standing cultural structures, community values and particularisms, and other such social authorities that fall victim to the ravenous hunger of liberal progressivism.

The consequence of this, as with all things telluric, material, or designed by human effort, is impermanence. Without reference to and deliberate denigration of being, ideas, concepts and structures formed within the liberal system have no permanent meaning; they are as fickle as the humans who constructed them. Roger Scruton eloquently surmised this conundrum when lambasting what he called the “religion of Rights”, whereby human rights, or indeed any concepts of becoming (without spiritual reference, or to being) are defined by subjective “moral opinions” and “legal precepts.” Indeed “if you ask what rights are human or fundamental you get a different answer depending whom you ask.” I would further add the proviso of when you ask, as a liberal of any given period appears to their successors as at best outdated or at worst reactionary. Plucking a liberal from 1961, 1981, 2001, and 2021, and sitting them around a table to discuss their beliefs would result in very little agreement. They may concur on non-descript notions of “freedom” and “equality”, but they would struggle to find congregate over a common understanding of them.

To surmise, any idea, concept or structure that exists within or is a product of liberalism is innately short-lived, as the ceaseless agitation of becoming necessitates its destruction in order to maintain the pace of the march of progress. But Actual people, regardless of how progressive or rational they claim to be, rarely keep up with this speed. They tend to follow Robert Conquest’s first law of politics: “everyone is conservative about what he knows best.” People are naturally defensive of the familiar; just as an aging iPhone slows down with time or when there’s a new update it can’t quite cope with, so too will liberals who fail to adapt to changing circumstances. Sadly for them, the progressive thirst of liberalism requires constant refreshment of eager foot-soldiers if its current flock cannot keep up, unafraid to put down any fallen comrades if they prove a liability, no matter how loyal or consequential they may have once been. Less, as Isaac Newton famously wrote, “standing on the shoulders of giants”, more “relentlessly slaying giants and standing on a pile of their fallen corpses”, which as far as I’m aware no one would ever outright admit to.

You don’t have to look particularly far to find recent examples of this. In the 1960s and 70s, John Cleese pioneered antinomian satire such as Monty Python and Fawlty Towers, specifically mocking religious and British sensibilities. Now, in response to his assertion that cultural and ethnic changes have rendered London “no longer English”, he is derided for being stuffy and racist. Indeed, Ken Livingstone, Boris Johnson, and Sadiq Khan, the three progressive men (in their own unique ways) who have served as Mayor of London since its establishment in 2000, lined up on separate occasions to attack Cleese, with Khan suggesting that the comments made him “sound like he’s in character as Basil Fawlty.” There is certainly a poetic irony in becoming the very thing you once satirised, or perhaps elegiac for the liberals who dug their own graves by tearing down the system, only to become the system and therefore a target of that same abuse at the hands of others.

Another example is George Galloway, a staunch socialist, pro-Palestinian, and unbending opponent of capitalism, war, and Tony Blair. Since 2016 however, he has come under fire from fellow leftists for supporting Brexit (notably, something that was their domain in the halcyon days of Tony Benn, Michael Foot, and Peter Shore) and for attacking woke liberal politics. Other fallen progressives include J. K. Rowling and Germaine Greer, feminists who went “full Karen” by virtue of being TERFs, and Richard Dawkins, one of New Atheism’s four horsemen, who was stripped of his Humanist of the Year award for similar anti-Trans sentiments. All of these people are progressives, either of the liberal or socialist variety, the difference matters little, but their fall from grace in the eyes of their fellow progressives demonstrates the inevitable obsolescence innate to their belief system. How long will it be until the fully updated progressives of 2021 are replaced by a newer model?

On a broader scale, we can think of it in terms of generational divides regarding social attitudes, where the boomers and Generation X are often characterised as the conservatives pitted against the liberal millennials and Generation Z. Yet during the childhood of the boomers, the United Nations was established and adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and when they hit adolescence and early adulthood the sexual revolution had begun, with birth control widespread and both homosexuality and abortion legalised. Generation X culture emerged when all this was fully formed, and rebelled against utopian boomer ideals and values in the shape of punk rock, the New Romantics, and mass consumerism. If the boomers were, and still are, ceaselessly optimistic, Generation X on the other hand are tiringly cynical. This trend predictably continued, millennials rebelled against Generation X and Generation Z rebelled against millennials. All of them had their progressive shibboleths, and all of them were made obsolete by their successors. To a liberal Gen Zer in 2021, it seems unthinkable that will one day be the crusty boomer, but Generation Alpha will no doubt disagree.

Since 2010, Apple’s revolutionary iPad has had 21 models, but the current could only look on in awe at the sheer number of different versions of progressive which have been churned out since the age of Enlightenment. As an object, the iPad has no choice in the matter. Tech moves fast, and its creators build it with the full knowledge it will be supplanted as the zenith of Apple’s capabilities within two years or less. The progressives on the other hand are inadvertently supportive of their inevitable obsolescence. Just as they were eager not to let the supremacy of their ancestors’ ideas linger for too long, lest the insatiable agitation of Whiggery be halted for a moment, their successors hold an identical opinion of them. Their imperfect human sluggishness will leave them consigned to the dustbin of history, piled in with both the traditionalism they so detested as well as the triumphs of liberalism that didn’t quite get with the times once they were accepted as given. Like Ozymandias, who stood tall over the domain of his glory, they too are consigned to a slow burial courtesy of the sands of time.

As much as planned obsolescence is a regrettable part of modern technology, so too is it an inescapable component of liberalism. Any idea, concept, or structure can only last for a given time period before it is torn down or has its nature drastically altered beyond recognition to stop it forming into a new despotic custom. Without reference to being, the world and its products are left purely in the hands of mankind. Defined by caprice, “freedom”, “equality”, or “democracy” can be given just as quickly as they can be taken, with little justification required other than the existing definition requiring amendment. Who decides the new meaning? And what happens to those who defend the existing one? Irrelevant, for one day both will be relics, and so too shall the ones that follow it. What happens when there is no more progress to be made? Impossible to say for certain, but if we are to take example from nature, a tornado once dissipated leaves behind only eerie silence and a trail of destruction, from which the only answer is to rebuild.

Post Views: 891