“There are a lot of people that are afraid, that are afraid of being Jewish at this time, and are getting a taste of how it feels to be Muslim in this country.”

Oscar-winning Susan Sarandon’s comments at a pro-Palestine rally in New York saw her dropped by her representatives, United Talent Agency. Sarandon is far from new to activism and politics, having spent her many decades in the spotlight discussing various issues. It seems that this time she may have gone too far, judging by the reaction of UTA.

The newest development in the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine/Hamas has captivated the world, from the United Nations to local councils. Governments at all levels across every country have voted on ceasefires, because county councils apparently have a lot of say in geopolitics.

What is arguably even more prominent is the input of our entertainers. One can easily browse X or Instagram for a few moments and find a litany of celebrities who have given their views on the conflict. As a general rule, said celebrities have called for a ceasefire. In response to conflict, calling for a ceasefire is treated as the obvious response- it’s easy to say, you don’t sound too partisan and it’s essentially saying you just don’t like war. Any more nuance than that isn’t really expected of anyone.

At the end of one such open letter, those who signed it stated that “the United States can play a viral diplomatic role in ending the suffering.”

The United States probably can, yes. Celebrities? Not so much.

Celebrities like to use their voices to amplify issues, from war and presidential endorsements to abortion and LGBT rights. One only has to look at the star-studded events held by Hillary Clinton in 2016 to see how celebrities gravitate towards politics. Considering Clinton boasted guests like Katy Perry and Beyoncé, it’s plain to see that it’s a voice politicians accept. You’ll find celebrities using social media, posting blacked out squares on Instagram in an apparent promotion of Black Lives Matter. Perhaps they’ll wear a pink hat to protest anti-abortion legislation.

They are well within their right to do this, as we all should be. They also generally reside in the country in which they protest. The issue, however, comes when celebrities meddle in geopolitics.

The conflict in the Middle East is not an easy one, despite claims to the contrary. It involves years of religious and ethnic fighting, controversial borders, terror, violence, and bloodshed. The sides cannot, and often will not, agree to terms. So precious is Jerusalem to religious groups that conflict in its holy sites is far from rare. Saying ‘oh let’s have a ceasefire’ may stop a few problems in the short term, but it’s not a permanent stop to generations of problems.

Most notably, celebrities may have a say in their collective fan communities, but they do not have any influence on geopolitics. Even Joe Biden, who the aforementioned open letter was directed at, did not listen. Meanwhile, both Palestine and Israel are doing what they believe they need to do to survive. Hamas is doing what they believe they need to do to eradicate Israel. They are not going to listen to someone with an Oscar nomination or a Top Ten song.

That’s not to say that we shouldn’t speak out about issues because we feel it won’t influence things. Celebrities have the right to talk about the conflict, but let’s not pretend that we should care what they think or that it has any influence on anything. Most of us- celebrities and normal people- do not have the expertise to properly understand the situation. We can take a moral stance, but let’s not pretend that celebrities are necessarily informed.

The action, however well intentioned, is almost always performative. Celebrities allow themselves to be almost bullied into saying something, anything, by fans so that they’re not cancelled. Look at Taylor Swift. Her platform and wealth are equally large, so much so that her general lack of political inclinations is met with side-eye at best, and boycotts at worst. We expect celebrities to act as moral leaders and arbiters, to the detriment of real discussion.

Perhaps one day we won’t expect celebrities to be geopolitical experts. Perhaps one day celebrities won’t feel the need to ensure that their views aren’t the most important in the room. Much as COVID and January 6 turned people into armchair experts in virology and treason laws, the conflict in the Middle East has made us all experts in international relations.

Celebrities, continue calling for ceasefires if you wish, but don’t expect Benjamin Netanyahu and Hamas to take you up on your advice.

You Might also like

-

The Campaign for Scottish Independence is back to Square One

‘Within the next five years, in one form or another, break-up is likely to come about’. These are not the reflections of an unhappily married man, but a pronouncement on the fate of Great Britain, as prophesied by none other than Tom Nairn, widely considered the intellectual flagbearer for Scottish nationalism up until his death last year. Most notable for his book The Break-up of Britain, which foretells the dissolution of the United Kingdom as a consequence of imperial decline, Nairn, delivering one of his final interviews, felt confident enough to declare that the hour was finally at hand, despite being ‘usually cautious about predicting timelines’.

Nairn wasn’t alone in his prediction. According to a Survation poll, when asked ‘How likely or unlikely do you think it is that there will be another referendum on Scottish independence in the next five years?’, 65% of Scots were of the opinion that it was either ‘Very likely’ ‘or ‘Quite likely’. Only 25% answered ‘Quite unlikely’ or ‘Very unlikely’. The 65% may indeed be correct; but if any such referendum is to take place within the given timeframe, Scottish nationalists will have to pray for a miracle to happen within the next week or so, seeing as the survey in question was conducted all the way back in October 2019. Nairn’s five-year prediction was made in 2020, which affords it slightly more leeway. Yet the odds that the Scottish National Party, which only months ago suffered a crushing defeat at the ballot box, is able to persuade the British government to grant them a second vote by next year are slim to none. The truth is that the nationalist cause hasn’t looked more hopeless since the result of the original Scottish Independence referendum in 2014.

Even that episode, in which the UK faced its first truly existential threat since England and Scotland were united in 1707, ended on a modestly optimistic note for separatists. While the result of the vote was 55-45 in favour of Scotland remaining in the UK, the fact that Alex Salmond, the leader of the Scottish National Party, had been able to secure a referendum from the British government in the first place – and that the ‘Yes’ side, as the pro-Independence side became known, had come so close to winning – was taken by many as a sure sign that the Union was on its last legs. Worse still for the ‘No’ side, the fact that Independence was more popular among younger voters seemed to suggest that the end of the UK was not only inevitable but imminent. Led by liberal activists whose passionate appeals invoked the rhetoric of earlier Independence movements in former British colonies, the nationalists’ quest for freedom from the English yoke became an end goal for progressives; it was merely a matter of time before the pendulum swung left, thereby slicing in half the nation-state that birthed the modern world.

Any doubts anyone may have harboured about the impending demise of the UK were surely dispelled by the political turbulence that followed the referendum – the general election a year later, the other referendum the year after that, if not the snap election that took place the year after that – which to onlookers home and abroad resembled the death throes of a spent entity. In particular, amidst the chaos that occurred in the wake of the UK’s vote to leave the European Union in 2016, the only thing anyone seemed to be able to predict with any certainty was that Scotland – which had voted 62-38 to remain in the EU – would jump ship at the soonest opportunity. (Around a third of Scottish voters even believed that there would be another referendum before the UK completed the Brexit proceedings.)

Indeed, for many unionists, the ostensible advantages of remaining within the European Union proved a deciding factor in their ‘No’ vote: a stronger economy, representation at the European Parliament, and facilitated travel to the continent. As part of the UK, Scotland was by extension part of the EU, and a newly independent Scotland would surely struggle to gain re-entry to a bloc which mandates a 3% deficit ratio for all member states, given that the nation’s deficit hovered around 10%. But the UK’s vote to leave the EU put a knot in that theoretical chain of consequences. Remaining in the UK became a guarantee that Scotland would be cut off from the EU, while Independence under the stewardship of the passionately pro-Europe Scottish National Party at least allowed for the possibility, however scant, of being ‘welcomed back into the EU with open arms as an independent country’, in the words of one MP.

Against this backdrop, even the most optimistic unionist would not have expected the status quo to hold. And yet, 10 years on from the 2014 referendum, Independence polls produce, on average, the same 55-45 split. So what happened?

As it turned out, while Britain’s decision to leave the EU predictably shored up support for the SNP, it also complicated the logistics of Independence. The smallest matryoshka in the set, Scotland would find itself not only isolated but vulnerable, separated by a hard border with its only contiguous neighbour. The country would have to decide between a customs union with England, Wales and Northern Ireland (which collectively constitute the greater part of Scotland’s trade) or with the much larger, but more distant, EU.

And while a number of sometime unionists found themselves suddenly on the ‘Yes’ side of the debate – including a contingent of high-profile figures, from the actors Ewan McGregor and John Hannah to the writers Andrew O’Hagan and John Burnside – a number of those who had voted ‘No’ in 2014 suddenly found themselves siding with the so-called ‘Little Englander’s. These Eurosceptic defectors were broadly comprised of what the commentator David Goodhart would go on to classify as ‘somewheres’: patriotic Scots, typically older and poorer, and defined by a profound attachment to the place they call home, as opposed to the cosmopolitan aloofness of ‘anywheres’. An understudied but significant section of society, Scottish ‘somewheres’ have been instrumental in preventing separatism gaining a majority in the almost weekly polls, considering how many elderly, unionist voters have passed away in the last ten years, and how many Gen-Z, overwhelmingly pro-Indpendence voters have aged into the electorate.

Then there was COVID. As with every other political matter, the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic in 2019 dramatically changed the nature of the Independence debate. Since pandemic response was a devolved matter, the four home nations took a competitive approach to dealing with the virus. While Prime Minister Boris Johnson was initially reluctant to impose lockdowns, Sturgeon lost no time in employing comparatively draconian measures, such as mask mandates and severe quarantine regulations. As a result, Scotland was able to boast a considerably lower death rate than England. Between January 2020 and June 2021, excess deaths in Scotland were only around 3% higher than average, compared with England, where they were 6 % higher. This measurable discrepancy had the effect of suggesting to many minds that not only was Scotland capable of handling its own affairs, but that government under the SNP was safer and more effective than direct rule from Westminster. For the first time, Independence polls consistently suggested that the ‘Yes’ side would win a hypothetical referendum..

But the momentum didn’t last. As the months passed, and particularly as Johnson was coerced into a stricter COVID policy, adopting many of the SNP’s own strategies, the gap in hospitalisation and death rates between each of the home nations narrowed to a pinpoint. Moreover, the UK had developed its own vaccine, and thanks to opting out of the EU’s vaccine rollout was able to conduct its vaccination campaign far more rapidly than any other European country.

From there it was all downhill for the SNP. In the summer of 2021, it transpired that the party had been misallocating donations and routinely lying about membership figures. Nicola Sturgeon, who had replaced Salmond as First Minister after the 2014 referendum, resigned in February 2023, citing gridlock around the Independence question. A month later Peter Murrell, Sturgeon’s husband and chief executive of the SNP, was arrested as part of a police investigation into the party’s finances, prompting the SNP’s auditors to resign as well.

Sturgeon was replaced as party leader by Humza Yousaf. But while the former First Minister had been able to command respect even from her adversaries, Yousaf, who lacked Sturgeon’s charisma and the prestige that comes with an established reputation, proved a far more divisive leader at a time when the party was crying out for unity. The fact that Yousaf only narrowly won the leadership contest, after his openly Presbyterian opponent had been slandered by members of her own coalition for espousing ‘extreme religious views’, did little to endear him to the Christian wing of his party. Perhaps most controversially, his decision to carry forward the Gender Reform Bill – which made it possible to change one’s legal gender on a whim by removing the requirement of a medical diagnosis – provoked derision from a public which still falls, for the most part, on the socially conservative side of the fence. Nor were progressives much impressed by his decision to end the SNP’s power-sharing agreement with the Scottish Greens.

Yousaf resigned after thirteen months in office and was replaced by John Swinney, one of the more moderate senior members of the party, but the damage to the SNP’s credibility had already been done. With less than two months to go until the UK-wide general election, Swinney had his work cut out for him when it came to convincing Scots to continue to put their trust in the scandal-ridden SNP. Independence polling returned to pre-COVID levels. However, for nationalists, such polls were less germane to the pursuit of a second referendum than the election polls, given that keeping a pro-Independence party at the helm in Holyrood was a necessary prerequisite to secession. As long as the SNP commanded a majority of seats, there was a democratic case to be made for holding another referendum. This had been Sturgeon’s argument during the 2021 Scottish parliament election campaign, which was, in her eyes, a ‘de facto referendum’. If the SNP were to end up with a majority of seats, she claimed, the party would have the permission of the Scottish people to begin Independence proceedings. (As it happened, they went on to win sixty-four seats – one short of a majority.)

The SNP had fewer seats in the House of Commons, but the nature of Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system meant they still enjoyed considerable overrepresentation. Still, if possessing forty-eight seats at parliament was not enough to secure a referendum from the British government, then plummeting to a meagre nine seats in the 2024 general election killed the prospect stone dead. As the Labour party made sweeping gains in Scotland and the UK more widely, the SNP suffered the worst defeat in its 90-year history. In a speech following the election, a dour-faced Swinney acknowledged the need ‘to accept that we failed to convince people of the urgency of independence in this election campaign.’ The party ‘need[ed] to be healed and it need[ed] to heal its relationship with the people of Scotland’.

It is difficult to take note of something that isn’t there, which is perhaps why, as Ian MacWhirter noted in a piece for Unherd, ‘It doesn’t seem to have fully dawned on the UK political establishment that the break-up of Britain, which seemed a real possibility only a few years ago, has evaporated’. The topic of Independence now rarely features in the news, and some of the biggest names associated with Scottish nationalism – not only Nairn and Burnside, but also Alasdair Gray, Sean Connery and Winifred Ewing – have passed away in the decade since the referendum. Meanwhile, younger Scots are turning away from nationalism in general, an unforeseen phenomenon which MacWhirter puts down to the fallout from Brexit, the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, a sequence of geopolitical shocks that has many Scots wondering whether the campaign to sacrifice the nation’s economy and security on the altar of identity might well be recklessly indulgent. ‘The Union is probably safer now than at any time since the Jacobites waved their claymores 300 years ago.’

If the SNP hope to bring the dream of Independence back to life, it will not be enough to rely on generational shift and the goodwill of the British government. An uphill struggle awaits the Independence movement. It will entail extensive repairs to the party’s image, providing clarity on issues such as currency, retention of the monarchy and the route to EU membership, and – perhaps hardest of all – presenting a clear case as to why Scotland would be better off as an independent nation. Until then, the Union looks set to enjoy a new lease of life.

Post Views: 374 -

Neoconservatism: Mugged by Reality (Part 2)

The Neoconservative Apex: 9/11 and The War on Terror

11th September 2001 was a watershed moment in American history. The destruction of the World Trade Centre by Muslim terrorists, the deaths of thousands of innocent American citizens and the general feeling of chaos and vulnerability was enough to turn even the cuddliest of liberals into bloodthirsty war hawks. People were upset, confused and above all angry and wanted someone to pay for all the destruction and death. To paraphrase Chairman Mao, everything under the heavens was in chaos, for the neoconservatives the situation was excellent.

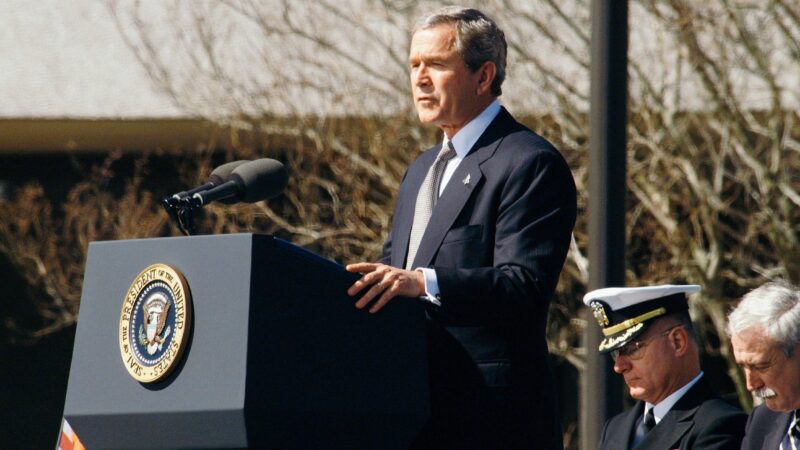

After 9/11, President Bush threw out the positions on foreign policy that he’d advocated for during his candidacy and became a strong advocate of using US military strength to go after its enemies. The ‘Bush Doctrine’ became the staple of US foreign policy during Bush’s time in office and the magnum opus of the neoconservative deep state. The doctrine stated that the United States was entangled in a global war of ideas between Western values on the one hand, and extremism seeking to destroy them on the other. The doctrine turned US foreign policy into a black and white war of ideology where the United States would show leadership in the world by actively seeking out the enemies of the West and also change those countries into becoming like the West. Bush stated in his 2002 State of the Union speech:

“I will not wait on events, while dangers gather. I will not stand by, as peril draws closer and closer. The United States of America will not permit the world’s most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world’s most destructive weapons.”

The ‘Bush Doctrine’ was a pure expression of neoconservatism. But the most crucial part of his speech was when he gave a name to the new war the American state had begun to wage:

“Our war on terror is well begun, but it is only begun. This campaign may not be finished on our watch – yet it must be, and it will be waged on our watch.”

The ‘War on Terror’ became a term that would become synonymous with the Bush years and indeed neoconservatism. For neoconservatives, the attack on 9/11 reaffirmed their pessimism about the world being hostile to the United States and, in turn, their views on needing to eradicate it with ruthless calculation and force. A new doctrine, a new President, a new war – neoconservatism certainly held itself up to its ‘neo’ nature. With all this set-in place and the neoconservative deep state rearing to go, they could finally start to do what they had always wanted to do – wage war.

Iraq and Afghanistan became the main targets, with Al Qaeda, Saddam Hussein and the Taliban becoming public enemy’s number one, two and three. A succession of invasions into both countries, supported by the British military, ended up with the West looking victorious. Both the Taliban and Saddam Hussein had been removed from power, Al Qaeda was on the run, and various of their top leaders had been captured or killed. It was ‘mission accomplished’ and thus time to remould Afghanistan and Iraq into American-aligned liberal democracies. Furthermore, the new neoconservative elite saw to demoralise and outright destroy all those who had been associated with the Hussein regime and Islamic radical groups and thus began a campaign of hunting down, imprisoning and ‘interrogating’ all those involved. However, this is where the neoconservative project would begin to fall as quickly as it had ascended.The Failure and Eventual Fall of Neoconservatism

A core factor to note is that the neoconservative belief that one could simply invade non-democratic and often heavily religious countries and flip them into liberal democracies proved to be highly utopian. As Professor Ian Shapiro pointed out in his Yale lecture on the Demise of Neoconservatism Dream, the neoconservative’s falsely believed that destroying a country’s military was equivalent to pacifying and ruling a country. The American-British coalition may have swiftly destroyed the armies of Hussein of Iraq and cleared out the Taliban in Afghanistan but they did not effectively destroy the support both had amongst the general population. If anything, the removal of both created an array of intense power vacuums which the neoconservatives could only seem to fill with corrupt American aligned Middle Eastern politicians as well as gun-ho Generals and neoconservative elites who knew very little about the countries they were presiding over.

One such example is Paul Bremer who led the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in Iraq after the Hussein regime was overthrown. His genius idea – that totally would get the Iraqi people on the side of freedom and democracy – was to disband the army and eradicate the Iraqi civil service and governmental authorities of those who were aligned with Hussein’s Ba’ath Party; terming it De-Ba’athification. Both led to a plethora of Iraqi’s losing their jobs and incomes and being smeared as enemies of the new American led regime – even low level teachers and privates were removed despite the fact that many of them joined the party simply to keep their own jobs.

While seen as a tactical way in which to remove any potential opposition to the CPA, the move created more opposition to the new government than any dissident anti-American group could have wished to have created – turns out making 400,000 young men, who know how to kill a man in sixteen different ways, unemployed isn’t the best way in which to show your care for the Iraqi people. It also didn’t help that Bremer and the CPA failed to account for a variety of funds and financial given to him for the reconstruction of Iraq, leading to a variety of financial blackholes and millions of dollars that simply disappeared.

Insurgent groups grew and assassination attempts on Bremer became commonplace to such an extent that even Osama Bin Laden himself placed a sizable bounty on Bremer’s head. Opposition to Bremer was so fervent that he was essentially forced to leave his position in the CPA by mid-2004 with his legacy being one of failure, instability and corruption, a legacy which the Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich called “the largest single disaster in American foreign policy in modern times”.

Removing opposition instead of attempting to work with it and use their expertise is something the US has done before, especially after WW2 with the fall of the Axis regimes, but the neoconservative mind has no tolerance or time for those who oppose American values – leading to brutal methods being used against those who do not comply.

It was under the neoconservatives that Guantanamo Bay was opened, a prison known for its mistreatment of prisoners and dubious torture methods. It was under the neoconservatives that Abu Ghraib prison, a feared prison under Hussein’s regime, became a place in which American soldiers and state officials were allowed treat and use interrogation methods on prisoners in manners that violate basic human dignity. And it was under the neoconservatives that began a mass surveillance state in their own country via the so-called ‘Patriot Act’ which put the privacy of American citizens in great danger. The Bush administration claimed that these abuses of human rights were not indicative of US policy, they were and the neoconservatives were the one’s responsible.

Luckily, these abuses were quickly all over mainstream news both inside and outside the US and horrified the population at large, even those who had once been pro the War on Terror. Furthermore, soldiers who had fought abroad came back with horror stories of their fellow soldiers abusing prison inmates and how they’d left Iraq bombed to the ground, displacing families and with casualty rates of up to and around 600,000 Iraqi civilians. The American mood turned against the war and by the end of Bush’s tenure in office 64% of Americans felt that the Iraq war had not been worth fighting.

The average American who felt angry and upset at their freedoms being threatened by Islamic terrorism became just as angry and upset when they saw their own country committing atrocities and taking away the freedoms of others. While it may seem cliche to point out the hypocrisy, this was one of the first times American’s had been exposed to the reality of what their state was really capable of. As Shapiro elucidates, the real legacy of the Iraq war and the War on Terror is that it destroyed America’s moral high ground. A high ground America has never been able to reach to since.

Barrack Obama and the Democrats attacked the Republicans and their neoconservative wing for their human rights abuses, the unjustified invasion of Iraq and implosion of America’s moral standing on the international stage. It is not unfair to say that Obama’s intoxicating charm and message of hope for America was desperately wanted in a post-Bush era in order so that Americans could try and forget the depravities that their country had fallen to in the early 2000s. He promised to pull out of Iraq, close Guantanamo Bay and replace the neoconservative doctrine for one based on diplomacy and moderation.

Bush and the majority of his neoconservatives left office after the election of Obama – in which he beat the then darling of the neoconservative right John McCain – and have since failed to re-enter the halls of power or indeed even their own party. The Tea Party movement supplanted neoconservatism dominance over the Republican Party and those still clinging on for dear life are being cleared out by the new America First aligned Republicans who wish to supplant the war-hawks and globalists with non-interventionists and nationalists.Conclusions

It is not radical nor unfair to say that not since the fall of the Berlin Wall has an ideological group lost its grip on power so completely as the neoconservatives have.

With the failure of nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan, the grotesque violation of individual liberties at home and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, neoconservatism, and indeed even the US government, became synonymous with warmongering, authoritarianism and out and out international crime. To quote Stephen Eric Bronner in his book Blood in the Sand:

“Like a spoiled child, unconcerned with what anyone else thinks, the United States has gotten into the habit of invading a nation, trashing it, and then leaving without cleaning up the mess.”

Neoconservatives like to hand-wring about the ‘evils’ of Middle Eastern dictators while they allow dogs to tear off the limbs of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, spy on innocent American citizens and bomb Afghani schools full of children into oblivion. Thanks to the neoconservative project of the early to mid-2000s – elements of which still are in place today – the United States became a leviathan monstrosity of surveillance, torture, corruption and warmongering.

It is interesting to see that after being the “cause célèbre of international politics”, neoconservatives are now the frequent targets of ridicule and scorn. And deservedly so, especially considering what neoconservatism has devolved into. The Straussian and genuinely conservative elements of the political philosophy have been ripped out, replaced with vague appeals to liberal humanitarianism and cucking for globalist organisations like the UN and NATO. The caricature of neoconservatives wanting drag queens to be able to use gender-neutral bathrooms at McDonalds in Kabul has shown to be somewhat accurate. After all, neoconservatives exist to promote ‘Western values’ in foreign countries, so naturally what they will end up promoting is the current cultural orthodoxy of progressive leftism, intersectionality and social decadence. An orthodoxy I’m sure Middle Easterners are desperately clamouring for.

However, despite their dwindling ranks and watering down of the ideology, the essence of neoconservative foreign policy remains intact; they still think the world should look like the United States. Therefore, it is unsurprising to see neoconservatives calling for every country in the world to be a liberal democracy along with the American model, or for Western troops to stay in Afghanistan indefinitely. Not only are these convictions still deeply held but are a direct expression of wanting American global hegemony to persist. On a deeper level, the recent pearl-clutching and whining from neoconservatives about the whole ordeal is simply a reflection of the anxiety that they now hold. Their ideas about what the world should look like have come collapsing before their eyes. And they can’t bear to face the fact that they were wrong.

This collapse has been occurring for some time and hopefully with the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, and the recent moves amongst elements of the right and left to adopt a more non-interventionist approach to foreign policy, the collapse of neoconservatism will remain permanent. After all, the neoconservatives who backed President Joe Biden – thinking he would spell a revival in their views – have now had an egg thrown in their face. Biden has proven himself to not be aligned with neoconservative foreign policy views.

Despite his claims that ‘America was back’ and his past support of foreign interventionism, it is evident that Biden has no real ideological attachment to staying in Afghanistan. In turn, he seems to have found it relatively easy to pull out and then spout rhetoric that wouldn’t be uncommon to hear at a Ron Paul rally. He stood against nation-building, turning Afghanistan into a unified centralised democracy and rejected endless military deployments and wars as the main tool of US foreign policy. Biden, alongside President Donald Trump, has turned the tide of US foreign policy away from military interventionism and back towards diplomacy. A surprise to be sure, but a welcome one.

However, while the ‘War on Terror’ may firmly be at an end – the American state has worryingly turned its eyes towards a new ‘War on Domestic Terror’. A war that political scientist and terrorism expert Max Abrahams worries will be catastrophic for the United States, quoting Abrahams:

“The War on Terror destabilized regions abroad. It’ll destabilise our country all the same… We cannot crack down on people just because we don’t like their ideology…otherwise the government is going to turn into the thought police and that is going to spawn the next generation of terrorists.”

The neoconservatives may have lost the war on terror but the structures and policies they put in place to fight that war are now being used, and being used more effectively, against so-called ‘domestic terrorists’. The American regime’s tremble in the lip is so great that it now believes the real threat to its existence lies at home. While this ‘War on Domestic Terror’ is still in its early stages, it is clear that the neoconservative deep state’s toys of torture, mass surveillance and war are now being put to other uses. Only time will tell if it will have the same consequences in America as it did in the countries it once occupied.

.

With the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan and Iraq; the continued rise of anti-interventionism on the right and left; and the memory of the failure of conflicts in the Middle East fresh in people’s memories, neoconservatism has been all but relegated to the ideological graveyard – its body left rot under the cold soil for eternity. A fitting fate.

“A neoconservative is a liberal who has been mugged by reality” proclaimed the godfather of the ideology. But in the perusal of utopian imperial ambitions it has now suffered the same fate – neoconservatism has been mugged by reality. A reality it so desperately and violently tried to bring to heel.

Post Views: 1,111 -

On Repression in Communist Hungary

The Hungarian People’s Republic (HPR), a communist puppet state which lasted between 1949 and 1989, is sometimes characterised as being propped up solely by Soviet military intervention. However, while Soviet intervention proved decisive during flashpoints such as the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the HPR’s existence was largely due to its intricate systems of internal repression.

In this article, we shall explore the HPR’s methods of social and political repression by looking at its three pillars: dismantling the Hungarian nationality, restrictions on speech, and political infiltration.

Dismantling the Hungarian Nationality

Nationalism directly contradicted Marxist-Leninist ideology, since loyalties to national identities were incompatible with global solidarity between workers. The HPR, like many Warsaw Pact nations, thus saw nationalism as an existential threat to its continued existence.

Rather than merely tackling the political manifestations of nationalism, the HPR sought to undermine the concept of a distinct Hungarian national and ethnic identity. By eroding the Hungarian identity, the HPR would eliminate any kinship ties that could challenge Marxist-Leninist universalism or be fed into nationalist political movements. Removing nationalistic feelings would also reduce domestic resistance to Soviet military and political interventions within the HPR during times of crisis.

The most important part of this strategy was the HPR’s project of educational “reforms”, which systematically undermined the historical basis of the Hungarian people. The regime rewrote school textbooks and university curricula to promote the idea of Hungary as being a ‘nation of migrants’ from its very outset. Rather than being founded in the 9th century by semi-nomadic ethnic Hungarians, this new history claimed Hungary was originally a ‘melting point’ of varied European, Eurasian, and Middle-Eastern peoples – one that was forcefully subjugated and “colonised” by a new elite that fabricated the Hungarian ethnicity.

The first Hungarian ruling dynasty, the Árpáds, was a particular target for HPR censors and “educationalists”, given its role in Hungarian ethnogenesis. As part of its efforts, the HPR claimed many historical figures were of foreign extraction: for example, HPR state media frequently portrayed King Saint Stephen (who reigned 1001 – 1038), as being an Ethiopian originally sent by his land’s Orthodox church.

Along with undermining the historicity of the Hungarian people and state, the HPR’s anti-Hungarian project also saw the state work to rapidly erode the presence of Hungarians across civil society. The HPR invited hundreds of thousands of migrants from the USSR and other Warsaw Pact members, initially justified on the grounds of replacing dead or missing Hungarians from WW2. Along with offering heavily subsidised social housing for these migrants, the HPR instituted quotas and incentives for these migrants across the economy – along with granting them preferential access to institutions like universities. Through quotas and subsidies, the HPR nurtured a non-Hungarian class in rapidly obtaining outsized influence across society and key institutions. Along with eroding the presence of native Hungarians in relevant institutions, these new arrivals were used by the HPR to justify its claims that Hungary was a “diverse melting pot” to the public.

Restrictions on Speech

It’s well-known that the HPR did not tolerate anti-communist or anti-state speech in public or private life. However, speech controls in the HPR expanded well beyond the remit of clamping down on challenges to the ruling party. Rather, restrictions on speech within the HPR largely were based on defending “Hungarian Values” – an undefined set of principles that roughly corresponded with support for egalitarianism, internationalism, and anti-nationalism.

The HPR was notoriously staunch in its defence of “Hungarian Values”, to the point that it would summarily arrest even senior functionaries for public utterances that were at tension with them. Decorated public careers could be brought to an end with even the vaguest nationalistic sentiments, with the courts fiercely prosecuting “racially aggravated public order offences”.

The HPR’s pursuit of “Hungarian Values” extended to the policing of private correspondence. Citizens were convicted, fined, and jailed for sending letters that included off-colour jokes about migrants or ethnic minorities. Suspected Christians were arrested on the spot for standing within a hundred metres of abortion clinics, under suspicion of silent prayer. Proto-nationalistic sentiments expressed in work canteens were reported to functionaries, who promptly forced workers to attend “diversity and equality training” – sessions which, in practice, required workers to explicitly announce their full commitment to “Hungarian Values” or face destitution.

Non-political newspapers and radio were often shut down based on non-conformity with “Hungarian Values”, via the HPR’s culture and propaganda ministry. Arts councils required productions to build endorsements of inclusivity, diversity, and other key state values into scripts from the outset. Even sports matches and their respective commentators were required to open and close games with pronouncements about the importance of “Hungarian Values”, with players and fans berated if their commitment was felt to be wanting.

Political Infiltration

So far, we have touched on how the HPR manipulated Hungarian society to preclude the existence of political opposition. However, the HPR also devoted considerable resources to defusing organised political opposition throughout its existence. The HPR’s secret police used whatever legal and extralegal means they had available to stop any serious political movement from gathering momentum.

The HPR did not simply “disappear” political dissidents on discovery. Instead, the HPR adopted a policy of “controlled opposition” via the infiltration of dissident political groups. This approach offered some significant benefits – the HPR could keep tabs on dissidents, and also draw out “extremists” who may have otherwise remained nonpolitical if there was a complete crackdown. Infiltration also ensured that dissident groups, no matter how large, directed their energies towards ineffectual and embarrassing ends that often served great propaganda value to the HPR.

For groups that were not sufficiently infiltrated but at risk of attracting popular support, the HPR employed a hands-off method to destroy them. One of the most notorious cases was that of the Hungarian National Party (HNP), a small nationalist group rapidly growing in popularity. The HPR destroyed the HNP by stealing a copy of its confidential membership list and “leaking” it to state media. Rather than the state having to arrest HNP activists, the movement simply imploded as most members found their employment abruptly terminated, and financial contributions ceased.

Conclusion

In this article, we have explored the three pillars of the HPR’s system of political and social repression.

- How the state deliberately eroded the idea of Hungarian nationhood through mass migration and the rewriting of Hungarian history.

- How an insidious concept of “Hungarian Values” was used to coerce speech to a degree impossible through brute force alone.

- How the secret police engaged in widespread infiltration of opposition political movements, with economic and social ruin being a resort when infiltration was insufficient.

At this point, I must now make a confession: the above article doesn’t describe Hungary. At least, not entirely or without occasional and selective embellishment. It describes the Britain of 2024.

Post Views: 662