Ride (read) or Die: 2023 Book Report (Part I)

Following on from last year’s experiment of attempting to read at least 10 pages of a book a day to increase my reading, I found it thoroughly enjoyable and wished to continue my reading journey in 2023. About halfway through last year, a friend of mine suggested to me that the 10 pages target could be detrimental to my overall reading, as it would encourage me to simply put the book down after just 10 pages (something I later realised it was doing). This year, I chose to do away with the 10 pages target and have decided to just make a pledge to read every day. In the first week of the year, I have already read considerably faster than last year, so I think perhaps my friend was on to something.

I also realised, reading back on last years review scores, that I was a very generous reviewer. I think this was because I did not have enough experience to know what made a book good or bad. I hope that my reviews can be more reflective of the overall reading experience this year.

Book 1: Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Read from: 01/01/2023 to 08/01/2023

Rating: 4/5

When I was about 12 years old, I read 1984. Perhaps a bit too young to fully grasp the meaning of the book, I was still obsessed by it. I fell in love the ‘alternative history’ genre, which is why I am so surprised that I did not read this book sooner. Aldous Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’ gave me a great deal of nostalgia for my younger reading days. It brought back that same feeling of intrigue and dread which I had felt whilst reading Orwell’s work.

The book is set in the distant future, about 600 years after Henry Ford developed the assembly line and mass production. Ford is revered as a sort of semi-deity amongst the population, who regularly use his name instead of ‘God’. A society which praises stability and predictability above all else, no one knows of passion or love, no one is born naturally (instead being birthed through artificial methods), and a rigorous caste system is enforced by making some people stupid, and some people clever during the artificial birth process – alphas sit at the top, and epsilons at the very bottom. Children are ‘conditioned’ to be extremely comfortable with the roles they have been given in life, and to actively avoid intermingling and seeking activities the controllers of the world deem wrong. Sex is easily acquired, and children are encouraged to engage in ‘erotic activities’ with each other from a very early age. People live shorter but considerably happier lives with little to no unpleasant experiences, and regularly take ‘soma’, a near perfect drug with no hangover or negative side effects.

One of the main characters of the book, Bernard Marx, is a misfit. A designated Alpha, he is considerably shorter than his peers, and has been marked out because of this (as shortness is linked to being a member of a lower caste). He doesn’t understand why he is unhappy with the system around him, but he feels uneasy about it. For example, he has a strong attraction to another alpha, Lenina Crowne, but doesn’t understand why. He is skirting along the fringes of ideas like monogamy and chastity but can’t quite explain why he would want this.

Bernard takes Lenina to a ‘Savage Reserve’ (an area designated as not worth developing), and accidentally meets with a man called John who, through no fault of his own, has been stuck on this savage reservation, with the actual savages, since birth. Bernard takes the savage back to civilisation to attempt to learn more from him and his strange ideas about love, modesty, romance, and passion.

I really enjoyed the literary devices employed by Huxley in the book. His writing style is straight forward and relatively easy to follow. Sometimes it felt a bit too straight forward, however, with only one predictable twist and an ending which felt a bit flat and unexciting. Still, however, it was a pleasant read which conveyed the stories message (that a world free from want and sacrifice is not necessarily a good one) in a way that was subtle and very interesting. Overall, a book that I would thoroughly recommend.

Book 2: Storm of Steel by Ernst Junger

Read from: 08/01/2023 to 14/02/2023

Rating: 5/5

This book was given to me by a very good friend. He had, by some miracle, found this 1941 copy in a second-hand bookshop. Knowing that I was desperate to get my hands on an original translation copy of Storm of Steel before I had sullied myself by reading a more contemporary translation, he bought it for me to read.

What a superb book. What a fascinating read. Ernst Junger takes us on an incredible journey through his experiences in the first world war as a young officer in the German army with immense attention to detail and a spectacular writing ability. Alongside his more general accounts of the fighting, Ernst interweaves his own thoughts on the state of warfare, the reasoning behind conflict, and the virtue in soldiering. Ernst does not shy away from declaring that taking part in the first world war was one of the most foundational and important experiences of his life. He seems to have genuinely enjoyed his time as a soldier and was sincerely disappointed at Germany’s surrender. His rationale behind these beliefs are interesting, and he goes in to great detail to explain his personal philosophy around conflict, and why he believes that soldiering is inherently a good thing.

Not only does Ernst make haste to convince you of the benefits of being a soldier, but he also goes into detail to describe what makes a good person, or more specifically, a good man. Ernst talks a lot of honour, courage, and honesty in his writing. He speaks of his enemies, the English and French, in high esteem, and tells the reader that he tried to keep his own men in good standards. He discusses the importance of valour and of dying with courage (he himself never surrendered and was wounded multiple times). His philosophy on this is very interesting and has been a very jarring counter to the mainstream ‘war is bad’ angle that is taken by other accounts of World War One.

The general structure of the book is good. Ernst tries to remain as consistent as possible with his timing and pacing. However, due to the nature of a book about a war, it is not always possible to keep pacing at a consistent rate. This is understandable and does not detract from the book. Just be aware that there are moments when nothing is happening which are suddenly punctuated by moments in which everything seems to be happening.

I would thoroughly recommend this book to anyone interested in the first world war. It has been an exciting and amazing read which has proven to be a favourite of the year so far. Thank you again to my friend Andrew for buying it for me, I appreciate it very much.

Book 3: The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

Read from: 14/02/2023 to 19/02/2023

Rating: 3/5

I only know about this book from various niche references and jokes on twitter. I assume this is one of those books that is compulsory for American High School students to read (as they seem to be the type most frequently discussing it online and in the review sections). The concept of the story interested me – a man becoming a bug, how absurd? But I really had no bias going into this book. I normally understand at least a little bit about the books I am reading before I read them, but I had absolutely no clue what I was getting into when I read this.

Kafka is known for his absurdist and transformative pieces of work, and I can understand why this short story has become his most famous. The book focusses on the story of Gregor Samsa, a travelling salesman who wakes up one morning to discover he has transformed into a giant bug. You would assume at this point that more context would be given, but no. Kafka doesn’t supply us with anything else – only the knowledge that Gregor is now a bug and must live as a bug. Being the sole breadwinner for his parents and sister, his metamorphosis causes immediate problems for all of them, and forces his relatives to actually go out and find work in order to support themselves for a change. All while this is happening, Gregor is stuck at home and simply crawls around, as a bug would. Gregor becomes completely dehumanised whilst his family struggle and cope with their new situation, eventually not even being referred to as ‘Gregor’ but simply as a monster.

The book’s theme is heavily centred on the idea of dehumanisation and alienation. Gregor is beloved and revered by his parents and sister because he earns a very good salary and keeps them well. As soon as he is no longer able to do that (Kafka using the transformation into a bug as a metaphor for ‘becoming useless’) his family still care for him but grow to despise him as they are forced to take up all of the work that he once did to support them. His family, however, do become stronger without him. Suddenly forced into the ‘real world’ again matures them all. His father takes up a respectable job and literally becomes stronger and healthier. His sister matures and develops into a ‘full woman’, and his mother is able to cope with the grief and stress of life at home again in a less pathetic way. Overall, the experience is not entirely bad for the family. Kafka is using this to reflect how dependence can make a person weak, and having the rug finally pulled from under them can improve their lot.

The book is extremely short and can be read in a few hours if you were really desperate to finish it. Kafka is know for his novellas and short stories, and this is no exception. Overall I liked the book but I felt no great connection to it. It was ‘fine’. I often found myself bored by it and couldn’t be bothered to continue reading. Kafka’s writing style is not my favourite in this piece of work. Overall I would recommend it (especially if you want to get the kudos for reading a classic novella in a short amount of time), but I would say that you shouldn’t expect something breath-taking, its an alright book. I hope the next few short stories I read of his are a bit more engaging.

Book 4: In the Penal Colony by Franz Kafka

Read from: 19/02/2023 to 19/02/2023

Rating: 4/5

I only own this book because my copy of ‘The Metamorphosis’ came with it as well (along with ‘The Judgement). Kafka’s stories are very short, so it makes sense that they would bundle them all together like this, and I am glad that I can get a few different stories all together in one book.

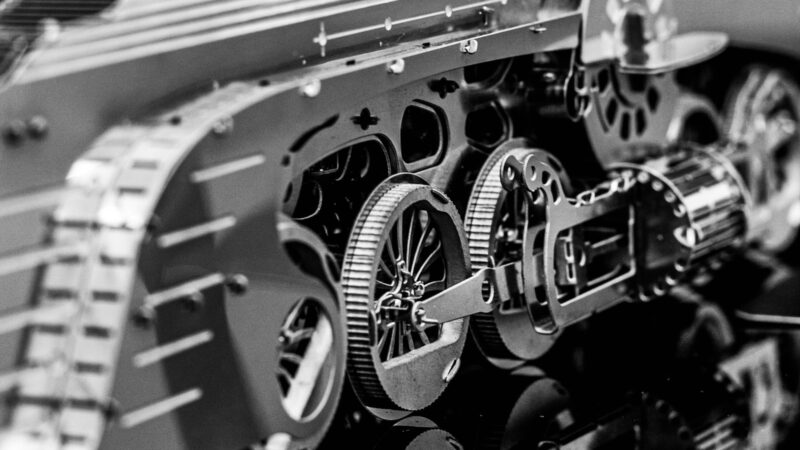

This story is a very narrow one. A nameless visitor to a nameless penal colony is being shown around a piece of equipment by a nameless officer whilst a nameless soldier and a nameless condemned man watch on. The officer goes on to explain that this piece of equipment is a torture and execution device which was created by the penal colony’s previous commandant who is now dead. The officer laments the condition of the machine and says that executions have become very unpopular after the commandant’s death, and he is the sole advocate for it now (with promises that a silent majority still agrees with him).

The officer is desperately excited to explain how the machine works in excruciating detail. He is extremely persistent in explaining to the visitor why it is so important and why it is an effective method of punishment.

The overall meaning of this book is difficult to grasp specifically, but can be read in different ways. It can be potentially read as a critique of totalitarianism, with the officer taking the law into his own hands and becoming a tyrant. The book can also be read as an analogy to the Old and New Testament (the old commandant being an analogy for God in the Old Testament and the new commandant being an analogy for God in the New Testament). Another common reading of the book is that it is a critique of carrying out acts which no longer have meaning or relevance to the bitter end – few people like the machine, so why does the officer continue to use it?

This book is very short and can be comfortably read in a day. I preferred this book to The Metamorphosis. I am not sure why, I just felt more inclined to want to read it. The flow of the story is more readable, and I found the characters and their plots more engaging, hence the 4 out of 5 star rating instead of a 3. If you’re looking for a short classic, I would recommend it.

Book 5: The Judgement: A Story for F. by Franz Kafka

Read from: 19/02/2023 to 20/02/2023

Rating: 4/5

Much like the previous book, I only read this because it was at the back of my copy of ‘The Metamorphosis’. This is a very short story, the shortest of the three that I have read so far. Owing to that, please don’t expect a long review as there is not a great deal to talk about.

The book is very narrow and focusses on only two main characters, a son and his father. The son is in the process of inviting his friend, who lives in Russia, to attend his wedding. His father, who is clearly senile and afraid of being forgotten by his son, has a very strange reaction to this – initially claiming he doesn’t know the Russian friend, before finally admitting that he does know him and then claiming that he, in fact, is a far better friend to the Russian than his son is.

It is difficult for me to explain this book more fully without giving too much away, as it is such a short story. But I do find it very odd. Kafka’s style of writing and his general themes continue to boggle and confuse me, but I am glad for this – it is quite refreshing to read things which are so absurd and strange.

The more I read his work, the more I become interested in Kafka. When I first started reading him, I was quite put off. I found his style very rough and difficult to ease in to. But, after getting more acquainted with his work, I’m actually starting to enjoy the lunacy. I have a much better grasp on what ‘Kafkaesque’ means now, and I would be more than happy to read more of his work in the future.

Overall, a good book which can be read in less than an hour. If you were interested in getting into Kafka, this is a good one to start with given its shortness. After doing some research, I also discovered that Kafka himself thought that this was one of his best pieces of work – yet another reason to read this if you wanted to ‘get into’ Kafka.

This is the first installment in a three-part series. Follow The Mallard for part two!