latest

Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better

Since Brexit, an embittered, drawn-out separation procedure which homogenised the UK’s political news for almost half a decade, political commentators have routinely surmised the future of the UK-EU relationship.

Whatever differences may exist in the specifics of their predictions, many operate under the pervasive assumption that the relationship is a work in progress – it doesn’t quite know what it is yet, it needs time to root itself into something tangible, which thereafter can be analysed at a deeper level.

Unfortunately for professional pontificators, the essence of the post-Brexit UK-EU relationship has already materialised: “anything you can do, I can do better.”

One might argue that every international relationship is like this. Even where this concord and sainted ‘co-operation’, the vying interests of states lurks beneath the surface.

Whilst it’s true that competition is an indelible component of politics, it’s worth noting that just because states can act in their own interests doesn’t mean they will. Now more than ever, the course of politics is dictated by PR, rather than policy.

As such, when policy considerations arise, states are prone to pursue goals which aren’t necessarily in their interests but provide a presentational veneer of ‘superiority’ when compared to rivals.

“Shot yourself in the foot, eh? What’s that? With a flintlock pistol? Pfft. Amateur.”

*Proceeds to aim cartoonishly large blunderbuss at own foot*

The UK’s ‘divorce’ from the EU was officialised over 3 years, yet both are desperate to ensure the other is perceived, well-in view of family, friends, and random strangers, as the cause for the nasty, bitter, and very well-publicised breakdown of relations.

In response to the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act, the world’s first AI regulatory framework, Paul Graham’s brief, but accurate, outline of the EU’s relationship with technology regained online attention:

America: Let's have a party. I'll bring the software!

— Paul Graham (@paulg) February 23, 2020

China: I'll bring the hardware!

EU: I'll bring the regulation!

America, China:

Following the EU’s announcement, the UK government announced their intention to one-up them. Prime Minister Sunak pitched Britain as the future home for AI regulation.

On the surface, it looks like the UK is one-upping the EU, beating them at their own game, doing EU tech policy more effectively than the EU themselves.

This wouldn’t be bad thing if the EU didn’t suck at tech, something even its most ardent supporters have admitted. It’s not a coincidence that none of the top 10 tech global companies are from the EU, or that every tech start-up leaves for (or gets bought-up by) the United States or China.

In America, you are told to “get out there and do it!” In China, you are told to “get out there and do it, or else.” In Europe, you are told to “sit tight as we process your application.”

Despite their differences, whether ‘entrepreneurial’ or ‘statist’ in their methods, both America and China have a far more action-oriented culture than Europe, which is inclined towards deliberation.

Given this, the UK is well-poised to become technophilic outpost in a seemingly technophobic region of the world – the beginnings of a positive post-Brexit vision.

The Prime Minister seems to, at the very least, loosely understand this fact, as the recent tweet gaffe would suggest, but continues to push the aspiration of turning Britain into Europe’s biggest bureaucratic wart.

However, this “Anything you can do…” attitude transcends the realm of tech policy, extending to other major areas, such as the environment and energy security.

Back in 2021, UK Environment Act came into force. Described by the government as the most ambitious environmental programme of any country on earth, the bill includes, amongst other loosely connected environmental commitments, new rules to stop the import of wood to the UK from areas of illegally deforested land.

Initially implemented as an expression of new powers acquired through Brexit, hoping to upstage the EU by implementing comparatively stricter environmental regulations, the EU have since ‘one-upped’ the Brits in pursuit of going green.

In December 2022, the European Commission approved a “first-of-its-kind” deforestation-free law: European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR).

EUDR is one of several measures by the EU to tackle biodiversity loss driven by deforestation and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, aiming to achieve net-zero by 2050.

Set to be implemented in December 2024, the EUDR prohibits lumber and pulp companies ensure from importing any material which has contributed to deforestation after December 2020.

Additionally, companies must know the origin of their products, ensure their products are produced legally in their country of origin, and obtain precise geolocation data for all the products they place on the EU market.

If companies fail to comply with the incoming regulations, they will not be allowed to sell their products on the EU market. Expectedly, companies with business practices in violation of the EUDR will face criminal charges, including non-compliance penalties of up to 4% of their EU turnover.

Putting aside snide comments about European pedanticism (isn’t selling lumber definitive proof of deforestation, what more proof do you need?!), this new regulatory framework is significant for two major reasons.

Firstly, the EU accounts for one-sixth of the global lumber trade and over $4 billion in tropical timber-related imports alone, contributing to the highest import value in a decade.

Whilst wood imports to the EU from Russia have declined, largely due to incrementally impose restrictions dating back to the 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia was still Europe’s main provider of wood, exporting (alongside Belarus and Ukraine) $6.71 billion’s worth of wood (including furniture) to the EU in 2022.

To provide such a strict and through regulatory framework for a market as large and as unprepared as the timber trade is ambitious, to say the least.

New data from the Zoological Society of London’s Sustainability Policy Transparency Toolkit (SPOTT) assessment shows only 13.3% of lumber and pulp companies are publicly monitoring deforestation within their own operations, and only 4.3% are monitoring their supplier’s operations.

Only 6.4% of the 90 companies surveyed by SPOTT are currently able to trace 100% of their supply to the location of harvest. Additionally, only 21.3% of companies report the processes they use to ensure suppliers comply with their legal requirements.

Secondly, during the winter of last year, firewood prices spiked, warehouses were placed under immense pressure, and crime (especially illegal logging) flourished, both in the EU and the UK.

In August 2022, firewood sales in the UK surged by a fifth, around which time wood pellets nearly doubled in France, Bulgaria, Poland, and several other EU counties, with practically all of Europe scrambling for firewood, drowning out the protestation of environmentalists.

Whilst this was certainly caused by Europe’s ‘green’ policies, such as the closure of Germany’s last operating nuclear power stations, and the embargos on Russian gas, leading people to source alternative sources of fuel, the EU’s less-than-publicised import ban of Russian wood and pellets in the month prior certainly did the trick.

Given that building up a reliable, long-term stock of relatively clean energy is politically untouchable, it’s safe to assume things will get worse, if not much better; that goes for both the Europe-wide energy crisis and the UK-EU relationship.

Indeed, “Anything you can do…” has trickled down into the media class. Several commentators have remarked that as Europe lurches rightward, the UK has remained a bastion of liberalism, on course to elect the centre-left Remainer-led party by a landslide.

This flies in the face of several important facts, such as Britain’s electoral system which does not reward upstart or fringe parties in the same way many EU countries do, or that Britons (when asked) generally display conservative views on immigration (and have done so for over 30-odd years), having arguably led the ongoing ‘right-wing populist revolt, etc, etc.’ with UKIP, Brexit, and the 2019 General Election, or that Christian, social, and liberal democratic still have a lot of electoral influence across Europe.

If Britain is a bastion of liberal/social democracy, and Europe is becoming a post-fascist conservative bloc, where does that leave their droopy-eyed fascination with ‘Bregret‘?

The rather boring reality is that the politics of the UK’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU will be non-existent. Policy agendas and goals remain aligned on a fundamental level, with the only ‘political’ tension constituting a war of nerves – in short, not especially political at all.

If it was political, there would be room to instate the reform our state so desperately requires.

Her Penis is Boring

Oh good. You get a package and creatively wrap it. Who doesn’t love a Dutch surprise?

It’s all very predictable. As soon as you see the headline, you know what’s going to happen.

A great big chunk of the normie right, and even the more based/red-pilled/dissident/whatever right, have reacted like this. What do you reckon, do you recognise the below?

“Outrageous! *What do they mean HER penis*? If the left did this eh meh meh hypocrisy blah! Harumph, most unorthodox! If a man did this! We’ve fallen so far, the future of our country, something something the Queen. Splutters champagne, monocle falls out, but with Victorian era mutton chops.”

OK, the last bit might be a little unfair. You get the point though, don’t you?

Is this really some great new surprise or at all shocking? No! It’s been done to death and now they’re acting out with increasingly more extreme things to get the same level of reaction, attention, etc. to try and keep any buzz or excitement going in their latest fad.

Now they’re getting their ‘tits’ out at the White House. What’s next? Synchronised helicopters at the Cenotaph this November while the King stands to attention? This is all so dumb and transparent. Why are you reacting as if it’s anything other than boring?

The ‘right’ is the most promising place anything new or interesting is likely to come from. It’s on the outside. It’s not establishment normalcy, curated and factory-made orthodoxy. When it reacts in such predictable ways to such obvious dreariness, it’s really letting itself down. Don’t let your enemies feel like insurgents when they’re cradled by the status quo. Let them jump the shark.

Reacting is a diversion of your energy from more important things. Minority issues cut both ways. Sure, ‘most people’ (do majorities matter, or does winning matter?) might agree with you, and it might even count for something, but how high on their list of priorities is it? Yes, take the low hanging fruit, or perhaps this is an issue which also largely takes care of itself if enough (of the relevant) people are on your side.

Yes, this may have played a role in bringing down Nicola Sturgeon, but how significant was that? What role did money problems play? And the SNP are still there, with Labour next best positioned to take over. Nothing big or culturally or politically is really that different in Scotland. For the whole UK what still stands? The economy, immigration, house prices, tax rates, NHS standards, take your pick of any issue which needs more work.

For now, let the TERFs and trans people have at it. It’s not like the TERFs are your friends. Why give any quarter to a slightly different strain of the progressive problem?

And on a totally basic level, isn’t it just stupid to bother fighting ‘to prove’ (to who?) that men are men and women are women? This is really just a playground case where someone calls you a name, and you either call them one back or ignore it. You don’t waste energy trying to persuade your accuser that you are not whatever they called you.

Just like the playground, they don’t really believe in ‘her penis’ anyway. It’s a shit test, ab initiation rite, an in-group/out-group signifier. It’s like molesting a pig to get into the Bullingdon Club or whatever. Well, that’s the Machiavellian side. A lot of these people are just useful idiots, aren’t party insiders, don’t have a clue, and really have the same energy as the ones who have the power of God and anime on their side. Either way, don’t bother. It’s stupid.

Are we really wasting energy on something as basic as this rather than just going “no” and carrying on with something real, something that might need more real fighting over?

Don’t waste the energy. They’re better prepared for it and you’re just feeding the trolls, following the paths they’ve laid out for you.

When you react in the ways they expect:

- They have their own set ways to react, and the game keeps going,

- They’re ready and waiting, don’t do what they expect and wrongfoot them,

- You keep their fad alive, and…

- It makes you look like you’re just doing the same old thing you’ve done since 2016 or whenever.

The more you disengage, the more they’ll look for a different game, or otherwise chase the high by pushing the absolute limits of their ideological/aesthetic paradigm. Eventually they run out of things to do, or it breaks, or people will get so totally disgusted by it that it provokes a real reaction. Interpret ‘reaction’ as you will.

Your instinct to react now is understandable, but it’s not useful. Yes, you’re right, progressives do get away with all sorts of things. On one level it’s because they have power to enforce what they want, defend their people, and you don’t. On another it’s because they have the kinds of religious fervent nutters who will throw bricks through people’s windows, glue themselves to roads, throw Molotov cocktails, etc. and your side doesn’t.

Well, OK, then you have to work with the people you’ve got. It means treating this for what it is. Boring!

Britain Is No Longer a Land of Opportunity

A recent viral tweet showed two doctors leaving a hospital. They’ve surrendered their licenses to practice medicine in Britain and are instead heading off to work in Australia. It’s not unusual- the majority of foreign doctors in Australia are Brits. The problem lies in the fact that young, educated doctors do not see themselves thriving in Britain. Our pay and conditions are not good enough for them.

Are you annoyed at them for being educated through taxpayer funding before going abroad? Many are. Are you understanding as to why? So are others.

Whilst this particular tale does come down to problems with the NHS, it’s also an example of what is wrong with Britain at the moment. People, especially younger ones, haven’t got the opportunities that they should have. There is no aspiration. There is a lot to reach for and not a lot to grab.

What has happened?

Wages and Salaries and Income, Oh My!

A recent investigation by a think tank has revealed that 15 years of economic stagnation has seen Brits losing £11K a year in wages. Let’s put this into perspective. Poland and Eastern Europe are seeing a rise in GDP- Poland is projected to be richer than us in 12 years should our economic growth remain the same. The lowest earners in Britain have a 20% weaker standard of living than Slovenians in the same situation.

That’s a lot of numbers to say that wages and salaries aren’t that great.

By historical standards, the tax burden in the U.K. is very high. COVID saw the government pumping money into furlough schemes and healthcare. As the population ages, there is a further need for health and social care support. This results in taxes eating into a larger amount of our income. In fact, more adults than ever are paying 40% or above in taxation. It’s a significant number. One might argue that this does generally only apply to the rich and thus 40% is not a high amount for them, but is that a fair number?

With inflation increasing costs and house prices rising (more on that later), a decent standard of living is beyond the reach of many. This is certainly true for young people. With wages and salaries falling in real time, we do not have the same opportunities as our parents and grandparents. Families used to be able to live comfortably on one wage, something that is near impossible. Our taxes are going on healthcare for an aging population.

Do we want old people to die? Of course not. We just do not have the benefits that they did. Our income is going towards their comfort. Pensioners have higher incomes than working age people.

Compared to the United States, Brits have lower wages. One can argue that it is down to several things- more paid holidays and taxpayer funded healthcare. That is true, and many Brits will proudly compare the NHS to the American healthcare system. That is fine, but when the NHS is in constant crisis, we don’t seem to be getting our money’s worth. The average American salary is 12K higher than the average Brit’s. The typical US household is 64% richer. Whilst places like New York and San Francisco have extortionate house prices, it’s generally cheaper across the US.

Which brings us onto housing.

A House is Not a Home

Houses are expensive- they are at about 8.8% higher than the average income. This is compared to 4% in the 1990s. That itself is an immediate roadblock to many. Considering how salaries have stagnated, as discussed in the previous section, it’s only obvious that homeowning is a dream as opposed to reality.

Rent is not exactly affordable either. In London, the average renter spends more than half of their income on rent. Stories of people queuing for days and landlords taking much higher offers are commonplace.

House building itself is not cheap- the price of bricks have absolutely rocketed over recent years. Factors include a shortage of housing stock and increased utilities. House building itself is also not easy.

NIMBYs have an aneurysm at the thought of an abandoned bingo hall being turned into housing. MPs in leafy suburbs push against any new developments, lest their wealthy parishioners vote for somebody else. Theresa Villiers, whose constituency sees homes average twice the U.K. mean price, led Tory MPs in an attempt to prevent house building targets.

We get the older folks telling us that we just need to work harder. It’s easy for them to say, considering a higher proportion of our income is needed to just get a damn deposit. If we’re paying more and more of our income on rent, how can we save?

Playing Mummy and Daddy

The ambition to become a parent is something many hold, but it is again an ambition that is unattainable. Well, the actual having the child part is easy, but it’s what comes after that makes it tough.

Firstly, we cannot get our own homes. Few want to raise their children in one bed flats with no gardens. To plan for a child is to likely plan a move.

Secondly, childcare is very expensive. Years and years ago, men went to work and women stayed home with the children as a rule. Of course, that did not apply to the working class, but it was a workable system. Nowadays, you both have to work. Few can survive on a single income from either parent. Grandparents are often working themselves or simply don’t/can’t provide babysitting duties. This leaves only one choice- professional childcare. The average cost of childcare during the summer holidays is £943. Some parents pay more than half of their wages on childcare.

Thirdly, as has been said, everything is more expensive these days. One only has to look at something basic like school uniforms- some spend over £300 per child. It’s not cheap to look after adults, let alone children.

The Golden Years

The focus of this piece is generally on young and working age people, but the cost of social care is pretty bad. With the costs of home and residential health care increasing constantly, it means that many will lose their hard earned savings. Houses must be sold and pensions given up. It is unfair that we must work all of our lives but then leave nothing for our children if we wish. Whilst residential homes are alien concepts to many in cultures where they look after the elderly, many factors in the U.K. mean that it is more common.

On balance, pensioners are better off than the young, but what about those who need care? It may be bad now, but what about when we ourselves are old? We will likely still be working at 70 and having to pay more for our care.

The Party of Aspiration and 13 Years of Power

The Conservatives have always called themselves the party of aspiration. They’ve been in power for 13 years, eight of which were without a coalition party. The Tories won a stunning majority in 2019 under Boris Johnson. They’ve had the opportunity to do something about this but haven’t. It’s amazing that they wonder why young people don’t vote for them anymore.

Let’s not pretend Labour and the Lib Dems are any better either. The Lib Dems won the historical Tory seat of Chesham and Amersham partially by appealing to those worried about new housing. Labour’s plans aren’t particularly inspiring.

We cannot dream in Britain anymore. The land of hard work and fair reward is no more. We must simply sit by as our wages stagnate, houses get too expensive and the opportunity for family passes us by. Our doctors head to Australia for better pay and better conditions. Countries that would see immigrants come to us for a better life are seeing their own economies grow.

People shouldn’t be living with roommates in their 30s when what they want is a family. We deserve to work hard to secure a good future. We don’t deserve for our income to go on poor services and for our savings to go on residential care.

The Tories have had thirteen years to sort it out. Labour and the Lib Dems have had chances to put their plans across. Our politicians care more about talking points and pretty photo ops than improving our lives.

Let us have ambition. Let us seek opportunities. Let Britain be a land of opportunity once again.

The Chinese Revolution – Good Thing, Bad Thing?

This is an extract from the transcript of The Chinese Revolution – Good Thing, Bad Thing? (1949 – Present). Do. The. Reading. and subscribe to Flappr’s YouTube channel!

“Tradition is like a chain that both constrains us and guides us. Of course, we may, especially in our younger years, strain and struggle against this chain. We may perceive faults or flaws, and believe ourselves or our generation to be uniquely perspicacious enough to radically improve upon what our ancestors have made – perhaps even to break the chain entirely and start afresh.

Yet every link in our chain of tradition was once a radical idea too. Everything that today’s conservatives vigorously defend was once argued passionately by reformers of past ages. What is tradition anyway if not a compilation of the best and most proven radical ideas of the past? The unexpectedly beneficial precipitate or residue retrieved after thousands upon thousands of mostly useless and wasteful progressive experimentation.

To be a conservative, therefore, to stick to tradition, is to be almost always right about everything almost all the time – but not quite all the time, and that is the tricky part. How can we improve society, how can we devise better governments, better customs, better habits, better beliefs without breaking the good we have inherited? How can we identify and replace the weaker links in our chain of tradition without totally severing our connection to the past?

I believe we must begin from a place of gratitude. We must hold in our minds a recognition that life can be, and has been, far worse. We must realize there are hard limits to the world, as revealed by science, and unchangeable aspects of human nature, as revealed by history, religion, philosophy, and literature. And these two facts in combination create permanent unsolvable problems for mankind, which we can only evade or mitigate through those traditions we once found so constraining.

To paraphrase the great G.K. Chesterton: “Before you tear down a fence, understand why it was put up in the first place.” I cannot fault a single person for wishing to make a better world for themselves and their children, but I can admonish some persons for being so ungrateful and ignorant, they mistake tradition itself as the cause of every evil under the sun. Small wonder then that their hairbrained alternatives routinely overlook those aspects of society without which it cannot function or perpetuate itself into the future.

And there are other things tied up in tradition besides moral guidance or the management of collective affairs. Tradition also involves how we delve into the mysteries of the universe; how we elevate the basic needs of food, shelter, and clothing into artforms unto themselves; how we represent truth and beauty and locate ourselves within the vast swirling cosmos beyond our all too brief and narrow experience.

It is miraculous that we have come as far as we have. And at any given time, we can throw that all away, through profound ingratitude and foolish innovations. A healthy respect for tradition opens the door to true wisdom. A lack of respect leads only to novelty worship and malign sophistry.

Now, not every tradition is equal, and not everything in a given tradition is worth preserving, but like the Chinese who show such great deference to the wisdom of their ancestors, I wish more in the West would admire or even learn about their own.

Like the Chinese, we are the legatees of a glorious tradition – a tradition that encompasses the poetry of Homer, the curiosity of Eratosthenes, the integrity of Cato, the courage of Saint Boniface, the vision of Michelangelo, the mirth of Mozart, the insights of Descartes, Hume, and Kant, the wit of Voltaire, the ingenuity of Watt, the moral urgency of Lincoln and Douglas.

These and many more are responsible for the unique tradition into which we have been born. And it is this tradition, and no other, which has produced those foundational ideas we all too often take for granted, or assume are the defaults around the world. I am speaking here of the freedom of expression, of inquiry, of conscience. I am speaking of the rule of law, and equality under the law. I am speaking of inalienable rights, of trial by jury, of respect for women, of constitutional order and democratic procedure. I am speaking of evidence based reasoning and religious tolerance.

Now those are all things I wouldn’t give up for all the tea in China. You can have Karl Marx. We’ll give you him. But these are ours. They are the precious gems of our magnificent Western tradition, and if we do nothing else worthwhile in our lives, we can at least safeguard these things from contamination, or annihilation, by those who would thoughtlessly squander their inheritance.”

Technology Is Synonymous With Civilisation

I am declaring a fatwa on anti-tech and anti-civilisational attitudes. In truth, there is no real distinction between the two positions: technology is synonymous with civilisation.

What made the Romans an empire and the Gauls a disorganised mass of tribals, united only by their reactionary fear of the march of civilisation at their doorstep, was technology. Where the Romans had minted currency, aqueducts, and concrete so effective we marvel on how to recreate it, the Gauls fought amongst one another about land they never developed beyond basic tribal living. They stayed small, separated, and never innovated, even with a whole world of innovation at their doorstep to copy.

There is always a temptation to look towards smaller-scale living, see its virtues, and argue that we can recreate the smaller-scale living within the larger scale societies we inhabit. This is as naïve as believing that one could retain all the heartfelt personalisation of a hand-written letter, and have it delivered as fast as a text message. The scale is the advantage. The speed is the advantage. The efficiency of new modes of organisation is the advantage.

Smaller scale living in the era of technology necessarily must go the way of the hand-written letter in the era of text messaging: something reserved for special occasions, and made all the more meaningful for it.

However, no-one would take seriously someone who tries to argue that written correspondence is a valid alternative to digital communication. Equally, there is no reason to take seriously someone who considers smaller-scale settlements a viable alternative to big cities.

Inevitably, there will be those who mistake this as going along with the modern trend of GDP maximalism, but the situation in modern Britain could not be closer to the opposite. There is only one place generating wealth currently: the South-East. Everywhere else in the country is a net negative to Britain’s economic prosperity. Devolution, levelling up, and ‘empowering local communities’ has been akin to Rome handing power over to the tribals to decide how to run the Republic: it has empowered tribal thinking over civilisational thinking.

The consequence of this has not been to return to smaller-scale ways of life, but instead to rest on the laurels of Britain’s last civilisational thinkers: the Victorians.

Go and visit Hammersmith, and see the bridge built by Joseph Bazalgette. It has been boarded up for four years, and the local council spends its time bickering with the central government over whose responsibility it is to fix the bridge for cars to cross it. This is, of course, not a pressing issue in London’s affairs, as the Vercingetorix of the tribals, Sadiq Khan, is hard at work making sure cars can’t go anywhere in London, let alone across a bridge.

Bazalgette, in contrast to Khan, is one of the few people keeping London running today. Alongside Hammersmith Bridge, Bazalgette designed the sewage system of London. Much of the brickward is marked with his initials, and he produced thousands of papers going over each junction, and pipe.

Bazalgette reportedly doubled the pipes diameters remarking “we are only going to do this once, and there is always the possibility of the unforeseen”. This decision prevented the sewers from overflowing in 1960.

Bazalgette’s genius saved countless lives from cholera, disease, and the general third-world condition of living among open excrement. There is no hope today of a Bazalgette. His plans to change the very structure of the Thames would be Illegal and Unworkable to those with power, and the headlines proposing such a feat (that ancient civilisations achieved) would be met with one million image macros declaring it a “manmade horror beyond their comprehension.”

This fundamentally is the issue: growth, positive development, and a future worth living in is simply outside the scope of their narrow comprehension.

This train of thought, having gone unopposed for too long, has even found its way into the minds of people who typically have thorough, coherent, and well-thought-out views. In speaking to one friend, they referred to the current ruling classes of this country as “tech-obsessed”.

Where is the tech-obsession in this country? Is it found in the current government buying 3000 GPUs for AI, which is less than some hedge funds have to calculate their potential stocks? Or is it found in the opposition, who believe we don’t need people learning to code because “AI will do it”?

The whole political establishment is anti-tech, whether crushing independent forums and communities via the Online Harms Bill, to our supposed commitment to be a ‘world leader in AI regulation’ – effectively declaring ourselves to be the worlds schoolmarm, nagging away as the US, China, and the rest of the world get to play with the good toys.

Cummings relays multiple horror stories about the tech in No. 10. Listening to COVID figures down the phone, getting more figures on scraps of paper, using the calculator on his iPhone and writing them on a Whiteboard. Fretting over provincial procurement rules over a paltry 500k to get real-time data on a developing pandemic. He may well have been the only person in recent years serious about technology.

The Brexit campaign was won by bringing in scientists, physicists, and mathematicians, and leveraging their numeracy (listen to this to get an idea of what went on) with the latest technology to campaign to people in a way that had not been done before. Technology, science, and innovation gave us Brexit because it allowed people to be organised on a scale and in ways they never were before. It was only through a novel use of statistics, mathematical models, and Facebook advertising that the campaign reached so many people. The establishment lost on Brexit because they did not embrace new modes of thinking and new technologies. They settled for basic polling of 1-10 thousand people and rudimentary mathematics.

Meanwhile the Brexit campaign reached thousands upon thousands, and applied complex Bayesian statistics to get accurate insights into the electorate. It is those who innovate, evolve, and grow that shape the future. There is no going back to small-scale living. Scale is the advantage. Speed is the advantage. And once it exists, it devours the smaller modes of organisation around it, even smaller modes of organisation have the whole political establishment behind it.

When Cummings got what he wanted injected into the political establishment – a data science team in No. 10 – they were excised like a virus from the body the moment a new PM was installed. Tech has no friends in the political establishment, the speed, scale, and efficiency of the thing is anathema to a system which relies on slow-moving processes to keep a narrow group of incompetents in power for as long as possible. The fierce competition inherent to technology is the complete opposite of the ‘Rolls-Royce civil service’ which simply recycles bad staff around so they don’t bother too many people for too long.

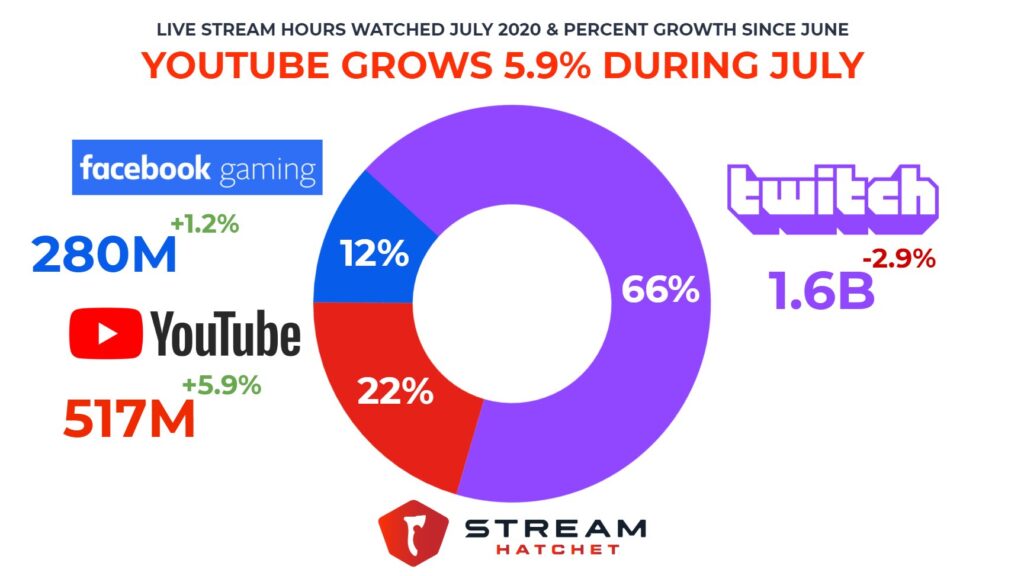

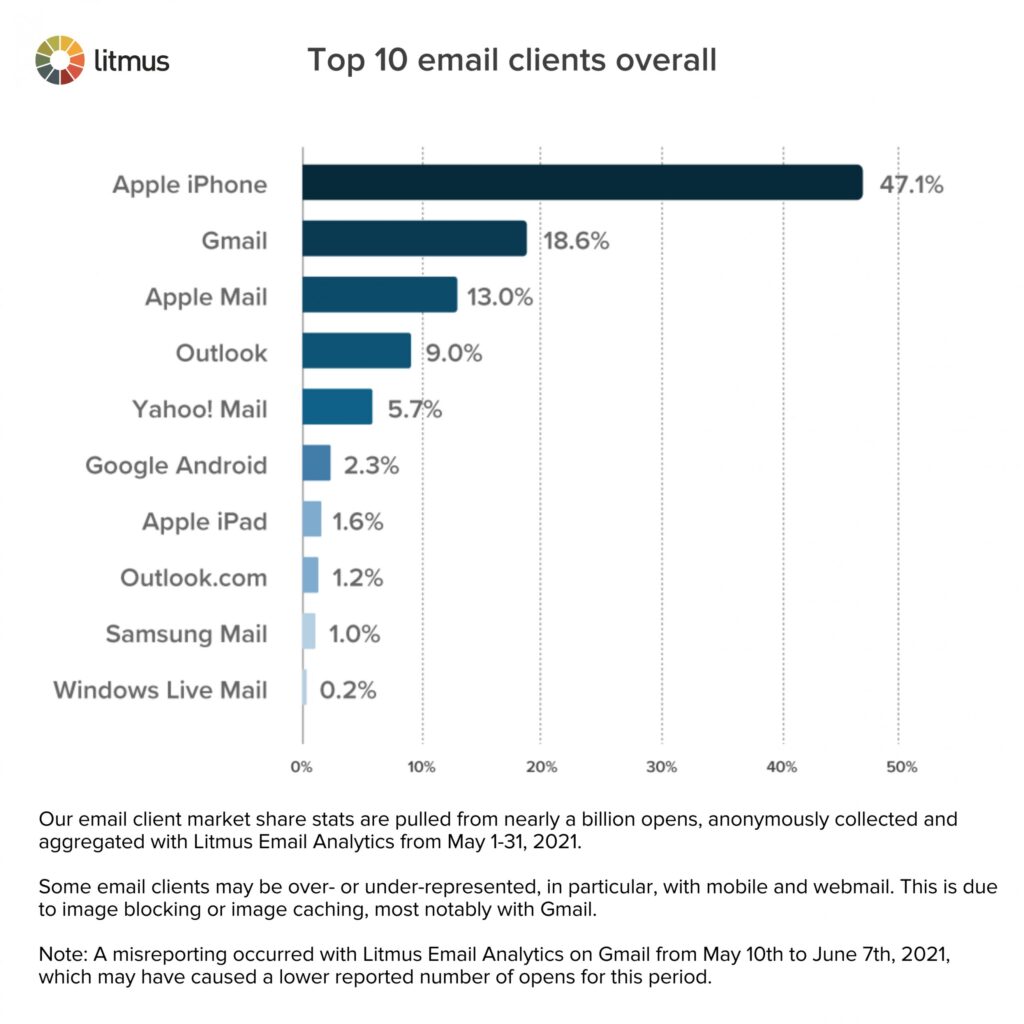

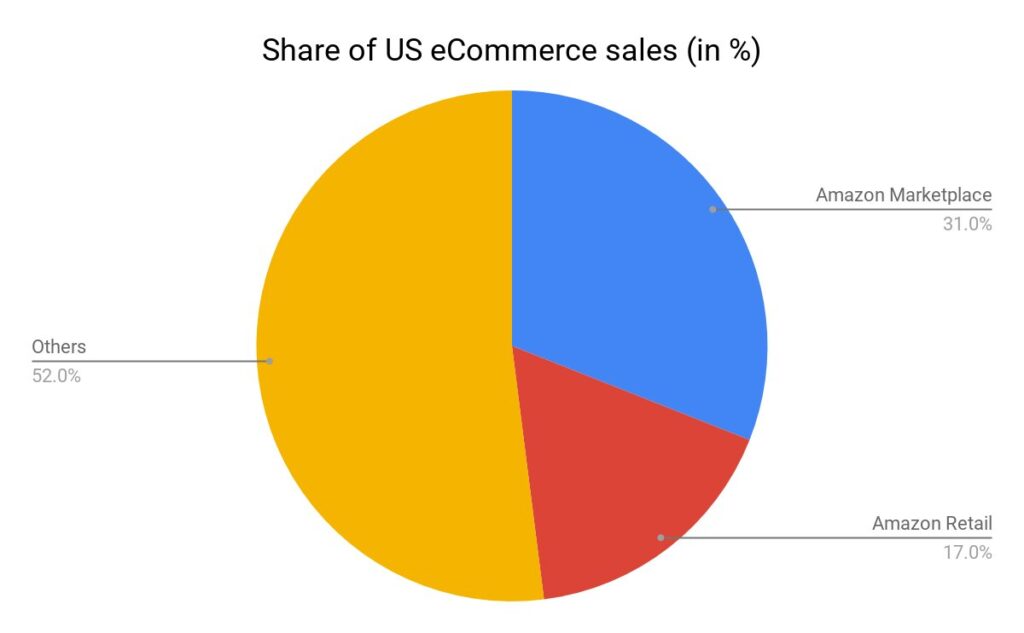

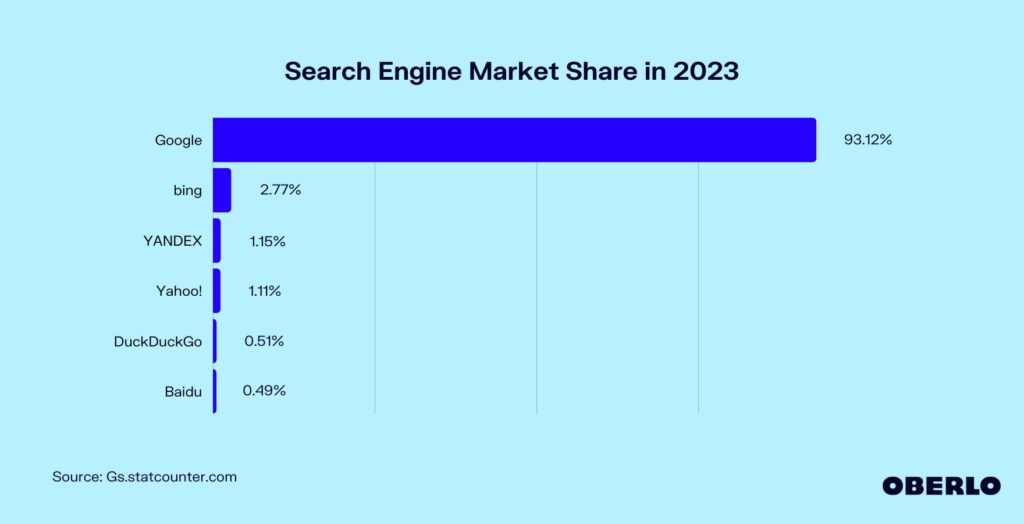

By contrast, in tech, second best is close to last. When you run the most popular service, you get the data from running that service. This allows you to make a better service, outcompete others, which gets you more users, which gets you more data, and it all snowballs from there. Google holds 93.12% of the search engine market share. Amazon owns 48% of eCommerce sales. The iPhone is the most popular email client, at 47.13%. Twitch makes up 66% of all hours of video content watched. Google Chrome makes up 70% of web traffic. There next nearest competitor, Firefox (a measly 8.42%,) is only alive because Google gave them 0.5b to stick around. Each one of these companies is 2-40 times bigger than its next nearest competitor. Just as with civilisation, there is no half-arseing technology. It is build or die.

Nevertheless, there have been many attempts to half-ass technology and civilisation. When cities began to develop, and it became clear they were going to be the future powerhouses of modern economies, theorists attempted to create a ‘city of towns’ model.

Attempting to retain the virtues of small town and community living in a mass-scale settlement, they argued for a model of cities that could be made up of a collection of small towns. Inevitably, this failed.

The simple reason is that the utility of cities is scale. It is the access to the large labour pools that attracts businesses. If cities were to become collections of towns, there would be no functional difference in setting up a business in a city or a town, except perhaps the increased ground rent. The scale is the advantage.

This has been borne out mathematically. When things reach a certain scale, when they become networks of networks (the very thing you’re using, the internet, is one such example) they tend towards a winner-takes-all distribution.

Bowing out of the technological race to engage in some Luddite conquest of modernity, or to exact some grudge against the Enlightenment, is signalling to the world we have no interest in carving out our stake in the future. Any nation serious about competing in the modern world needs to understand the unique problems and advantages of scale, and address them.

Nowhere is this more strongly seen than in Amazon, arguably a company that deals with scale like no other. The sheer scale of co-ordination at a company like Amazon requires novel solutions which make Amazon competitive in a way other companies are not.

For example, Amazon currently owns the market on cloud services (one of the few places where a competitor is near the top, Amazon: 32%, Azure: 23%). Amazon provides data storage services in the cloud with its S3 service. Typically, data storage services have to handle peak times, when the majority of the users are online, or when a particularly onerous service dumps its data. However, Amazon services so many people – its peak demand is broadly flat. This allows Amazon to design its service around balancing a reasonably consistent load, and not handling peaks/troughs. The scale is the advantage.

Amazon warehouses do not have designated storage space, nor do they even have designated boxes for items. Everything is delivered and everything is distributed into boxes broadly at random, and tagged by machines so the machines know where to find it.

One would think this is a terrible way to organise a warehouse. You only know where things are when you go to look for them, how could this possibly be advantageous? The advantage is in the scale, size, and randomness of the whole affair. If things are stored on designated shelves, when those shelves are empty the space is wasted. If someone wants something from one designated shelf on one side of the warehouse, and something from another side of the factory, you waste time going from one side to the other. With randomness, you are more likely to have a desired item close by, as long as you know where that is, and with technology you do. Again, the scale is the advantage.

The chaos and incoherence of modern life, is not a bug but a feature. Just as the death of feudalism called humans to think beyond their glebe, Lord, and locality, the death of legacy media and old forms of communication call humans to think beyond the 9-5, elected representative, and favourite Marvel movie.

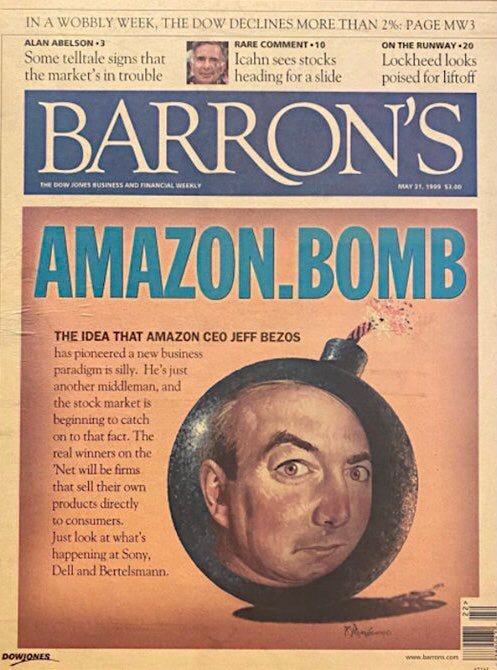

In 1999, one year after Amazon began selling music and videos, and two years after going public – Barron’s, a reputable financial magazine created by Dow Jones & Company posted the following cover:

Remember, Barron’s is published by Dow Jones, the same people who run stock indices. If anyone is open to new markets, it’s them. Even they were outmanoeuvred by new technologies because they failed to understand what technophobes always do: scale is the advantage. People will not want to buy from 5 different retailers because they want to buy everything all at once.

Whereas Barron’s could be forgiven for not understanding a new, emerging market such as eCommerce, there should be no sympathy for those who spend most of their lives online decrying growth. Especially as they occupy a place on the largest public square to ever occur in human existence.

Despite claiming they want a small-scale existence, their revealed preference is the same as ours: scale, growth, and the convenience it provides. When faced with a choice between civilisation in the form of technology, and leaving Twitter a lifestyle closer to that of the past, even technology’s biggest enemies choose civilisation.

Kino

Featured

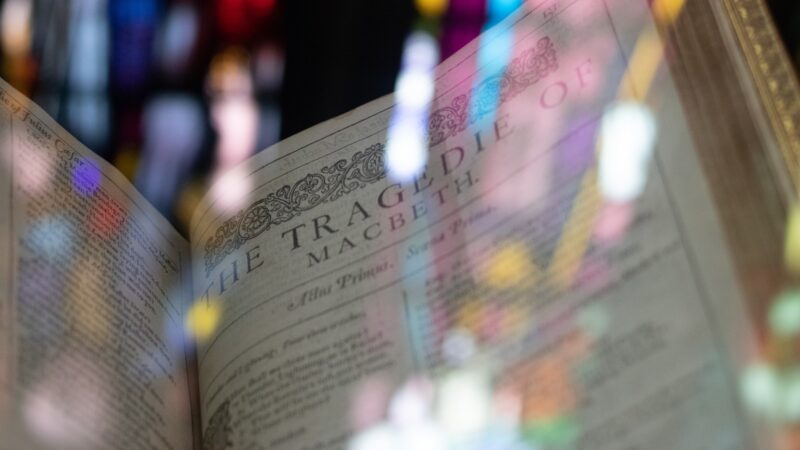

Dark Humor for the Red King: The Drunk Porter in Macbeth

“Knock, knock—who’s there?”

Whenever one of my tutorial students is assigned (or, let’s be honest, barely mentions) Macbeth, I go into a certain and by now well-rehearsed tangent on how Shakespeare’s arguably darkest play contains one of the most peculiar scenes in his canon—and the origin of what is now considered a passe pretext to employ a bad pun, the knock-knock joke. Mentioning that last part usually lands me at least a few minutes of fleeting teenage attention, wherein I talk about everything from Shakespeare, to dark humor, to how Shakespeare’s darkest tragedy produced one of our lightest joke forms.

Of course, the knock-knock joke, as we know it, owes less to Shakespeare than to the innovation of 1930s English radio host Wee Georgie Wood, with his turning the Porter’s words into his catch phrase of “knock, knock, who’s there?” By the middle of the Great Depression, when the average Joe and Jane were presumably in need of an easy laugh, the joke form was sufficiently popular in the US that a Columbus, OH, theater’s contest for the best knock-knock jokes was “literally swamped” with entries (I’m sure the $1 cash prize didn’t hurt the contest’s popularity). The popularity of the supposedly low-humor knock, knock joke amidst the depression (both economic and psychological) may not owe anything directly to Shakespeare, but I do think it relates back to the original Porter scene, which is the main subject of this article.

My purpose here is not to provide a definitive reading of the Porter’s monologue, nor to ultimately solve the puzzle of what, exactly, the scene is doing in the play; better scholarship is available for those interested than the motes I will, nonetheless, offer here. My aim is to consider what Shakespeare’s following arguably the least justified regicide in his canon with a comical drunk can tell us about humor’s role in helping people navigate tragedy. And, if it sheds light on why knock, knock jokes (or other seemingly low, tactless, or dark forms of humor) may grow especially popular in uncertain times, so much the better.

“Here’s a knocking indeed!”

Macbeth Act 2 Scene 3

[Knocking within. Enter a Porter.]

PORTER Here’s a knocking indeed! If a man were

porter of hell gate, he should have old turning the

key.

The lone on-stage partaker in the carousing at King Duncan’s visit to Inverness, the drunken Porter is one of the play’s few examples of plebians not directly connected with the nobility. However, unlike Hamlet’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the Porter remains, like a latter day Falstaff, insulated against the intrigue that surrounds him by drink, imagination, and low jokes.

Brought onstage by the knocking of MacDuff and Lennox (as if in ironic answer to Macbeth’s present wish that Duncan might wake), the Porter shows that, like Macbeth, he has a very active imagination. In fact, since Coleridge’s dismissal and omission of the scene as an inauthentic interpolation, many 20th-century critical readings have safely secured it back in its rightful place by pointing out, among other things, the Porter’s not merely contrasting but paralleling his master. Presumably rudely awakened and hungover, he fancies himself the porter of Hell and in the employ of a devil. Of course, the supreme irony throughout the scene involves his ignorance of how close to the truth his fantasy comes.

(Knock.) Knock, knock, knock! Who’s there, i’

th’ name of Beelzebub? Here’s a farmer that hanged

himself on th’ expectation of plenty. Come in time! 5

Have napkins enough about you; here you’ll sweat for ’t.

The Porter imagines admitting three denizens, each of whom, scholars have noted, can stand as a metaphor for Macbeth and his actions. The first imagined entrant is a farmer who, having hoarded grain in expectation of a shortage, hangs himself at the price drop produced by a surplus. As the play, if not the tragic genre, itself, is about the ends not aligning with expectation, the image of the farmer of course foreshadows the results of Macbeth’s betting too much on the Weird Sisters’ presentiments. Although in the end it is Lady Macbeth who commits suicide, Macbeth’s language near the end becomes more fatalistic the more vulnerable he gets, with his final fight with the prophesied MacDuff amounting to arguable suicide (to see an excellent rendition of the swap of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth’s psychologies by play’s end, see Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth—and my review of it). Adding to the irony of the scene is the fact that, according to Christopher Jackson, Shakespeare, himself, was an investor in and hoarder of grain against shortages. One wonders how many times he had thought of the image before writing this scene—and if he smirked while employing it.

(Knock.) Knock, knock! Who’s there, in th’

other devil’s name? Faith, here’s an equivocator

that could swear in both the scales against either

scale, who committed treason enough for God’s 10

sake yet could not equivocate to heaven. O, come in,

equivocator.

Next in the Porter’s fantasy is an equivocator, one whose ambiguous use of language can help him with earthly scales but not heavenly. Historicist critics point to this moment as an allusion to the Jesuit father Henry Garnet, executed in 1605 for his participation in the Gunpowder Plot (to which 1606’s Macbeth can be read as a reaction). In his trial, Garnet was criticized for equivocating to keep from revealing details of the plot without explicitly lying; he was subsequently hanged, drawn, and quartered in May 1606.

While said reference is informative, if nothing else, about Shakespeare’s possible view of the Gunpowder Plot (unsurprising to anyone who knows what happens to regicides in his canon), one’s reading should not stop there. The Porter’s landing an equivocator in Hell points, again, to the play’s titular character. It should be remembered that before he commits the play’s central tragic act, Macbeth goes through a rigorous process of thought to spur himself to the deed, often playing on or completely omitting language—that is, equivocating—to justify the assassination (which, as a word, is first used in English in his “If it were done when ‘tis done” speech in I.7; not carrying the weight it does today, the coinage was an example of Macbeth distancing himself from the reality of the murder).

Furthermore, the Porter’s focus on equivocators here and later in the scene (he displays some comic equivocation of his own on the virtues and dangers of drink, unknowingly stalling MacDuff and Lennox long enough for Macbeth and Lady M. to cover up Duncan’s murder) foreshadows Macbeth’s beginning “To doubt the equivocation” of the Weird Sisters’ prophecy about Birnam Wood’s coming to Dunsinane (V.5). Indeed, the infernal dangers of ambiguous language (or of trusting one’s initial interpretation thereof) constitute one of the play’s primary themes. Among other things, Macbeth’s pointing this out establishes a further parallel between the Porter and himself.

(Knock.) Knock, knock, knock! Who’s

there? Faith, here’s an English tailor come hither for

stealing out of a French hose. Come in, tailor. Here

you may roast your goose.

The last of the Porter’s imagined wards has landed in Hell for cheating English courtiers while providing them with French fashion; whether he played on his customers ignorance of how much the new fancies cost or whether Shakespeare—err, the Porter—is making a joke about French fashion being worthy of eternal damnation, I’ll decline to decide. Perhaps both readings (or one I’m missing entirely) are meant, offering sympathetic humor to both courtiers who have been gulled with exaggerated prices and to the commons who might enjoy a good skewering of the foppish trends of their betters. The dual metaphor of the roasted goose—referring both to a tailor’s hot iron called a “goose” and to the idiom “his goose is cooked”—continues the play’s theme regarding the dangers of trying to succeed through proscribed means, besides adding to the dramatic irony of the Porter’s describing his own boss’s trajectory.

(Knock.) Knock, knock! 15

Never at quiet.—What are you?—But this place is

too cold for hell. I’ll devil-porter it no further. I had

thought to have let in some of all professions that go

the primrose way to th’ everlasting bonfire. (Knock.)

Anon, anon!

The Porter, like Macbeth, seems to have an imagination as limitless as it is abysmal—such that he could presumably find a place in it for individuals of all professions. Also like his master, he fantasizes about a position higher (or, rather, lower) than he currently holds. That he stops not for lack of imagination but for the prosaic physical discomfort of being cold contrasts with how Macbeth eventually gives up all comforts in trying to achieve the crown. However, even here he parallels Macbeth, as both are ultimately unable to keep reality—whether the cold or the vengeance of the prophesied MacDuff—from interrupting their fantasies.

And yet, that the Porter identifies Inverness, itself, as too cold to sufficiently imagine Hell is, itself, a possible nod to the, under James I, verboten Catholic-Thomistic-Aligherian view of Hell’s lowest levels as being the frozen lake of traitors. However, Shakespeare skates past the Protestant censors, for it is not Hell the Porter is describing, but Scotland, and at its center at the very moment preceding this scene is not Satan, or the traitors Judas, Brutus, or Cassius, but Macbeth—who is, of course, all of these.

“…it provokes and unprovokes…”

But why does the Playwright link the worst regicide in his canon to a comic scene? Of course, as I mention above, plot-wise the Porter stalls the discovery of the play’s central crime. Furthermore, thematically the Porter both contrasts and mirrors Macbeth, which in different eras has been interpreted as alternatively demonizing the latter by the monologue’s subject and humanizing him by stressing a congruence with the common man.

The impropriety of the scene—joking about souls lately gone to Hell, when the unshriven Duncan, himself, has just entered the afterlife—highlights the very tension from which the Jacobean audience may have needed relief. As has been pointed out, an assassination plot against James I and Parliament had just the year before been foiled. Moreover, set in a medieval context where the death of a monarch had cosmic repercussions, the choice to distance the focus from the play’s main action may have been meant to increase the suspense—here, not merely the suspense before an expected surprise, but also the chaotic metaphysical suspension between monarchs—rather than comically relieve it. And this is assuming the comic relief does not fail due to its utter tactlessness, or to a high number of Malvolios in the audience determined to see the scene as an interruption of the play’s sombre pathos.

And yet, even being outraged by dark humor accomplishes the humor’s possible goal of helping one navigate a tragedy. For that is what I believe this scene—and most dark humor—is meant to accomplish: facilitate the audience’s psychological survival of the author’s darkest tragedy. Both inappropriate laughter and rage at impropriety—and even confusion about the scene’s strangeness—are preferable to the despair that leads eventually to Macbeth’s nihilism and Lady Macbeth’s suicide.

The Porter is not a good guy; indeed, his humor, like Falstaff’s, inheres in his being disreputable. Similarly, the scene is not openly funny, nor does it offer any kind of saccharine “everything will be alright” triteness. I, myself, am not satisfied to read it the way the play at large has conventionally been interpreted, as an implicit promise that divine justice will prevail and Macbeth will get his comeuppance like the farmer, equivocator, and tailor do; there are too many questions about Scotland’s future left unsatisfied by play’s end to settle on such a reading, just as there are arguably as many parallels between Macbeth and the play’s hero MacDuff as between Macbeth and the Porter. Rather, the scene’s salutary power paradoxically lies in its pushing the horror of Duncan’s murder even farther—by joking about souls lately knocking at Hell’s gate, with the Porter standing in as a kind of anti-St. Peter at the Pearly Gates. In so doing, the Porter scene lampoons the Macbeths’ expectation that they can somehow cheat fate, and his scene, more than the one before it, foreshadows the trend of the rest of the play.

As with the subtext of other examples of ironic humor, the Porter is not mocking the sympathetic Duncan, but implicitly commiserating with him and other victims of fate, fortune, or perfidy. By following Macbeth’s crime with a drunken Porter utterly disconnected from it who, nonetheless, perfectly names and exagerrates the themes involved, Shakespeare subsumes the play’s tragic act into the absurd, at least for a moment—and a moment is all that’s needed. By pointing out the reality of the play’s horror while safely containing it within a hyperbolically ironic, almost Chaucerian, tableaux, Shakespeare sets the standard for how well-placed instances of low and dark humor—from knock-knock jokes to self-deprication to suicide memes—can help contextualize tragedy, depression, and trauma in manageable ways.

One might balk (quite rightly) at the idea of telling a joke right after a tragedy like the assassination of a beloved king, considering it too soon and not the time for humor, but Shakespeare? Apparently he thought that was exactly when to employ humor—especially of a certain darker yet therapeutic type. It’s taken a few centuries, but scientific studies, so far as they go, have caught up with and confirmed Shakespeare’s using such humor as a way to help his audiences regulate their emotions in his plays’ more dreadful moments. Far be it from us to censure what the Playwright thought within the pale—and how dare we dismiss even the humble knock, knock joke as anything but profound and, sometimes, just what we need.

Against Common Sense Conservativism

What a sad and wretched world we live in. The decline of Free Speech, British Values, and Common Sense has let the loony left and Radical Woke Nonsense destroy our Institutions.

Remix these words enough and you too can qualify to be a conservative commentator in the contemporary British political landscape. Looking across the commentariate of the right wing, you’d be forgiven for believing that these figures were grown in test tubes. One part ‘cultural Christian’ (with “mixed feelings” on gay marriage and abortion), another part straight-talker, with a dash of ‘political incorrectness’ (always tempered by a well-to-do attitude) and some kind of minority identity as a sting in the tail for the left, and you’ve got a Common Sense Conservative.

The Common Sense Conservative isn’t hard to find: they fill the ranks of GB News and do the talking for Talk Radio – what underlines the whole project is a constant bewilderment with the modern world, and an ability to formulate programmatic responses to the latest trends from the left wing. They are the zig to the liberal zag, but both invariably pull in one direction – towards more of the general decay they claim to lament.

One Common Sense Conservative is very quick to point out that identity politics allegedly places an expectation on what he, a non-white man should believe. This, in his view, is a form of racism, which ipso facto debunks identity politics. What goes undiscussed, is that the dispute between the Common Sense Conservative and the “Woke Left” (who are really just more internally consistent leftists) is simply the narcissism of small differences. The leftist project of the modern world is one of liberation, where liberation is defined as the absence of restraint. Identity politics comes to be viewed by the Common Sense Conservative as one such restraint, and must therefore be rejected. The fundamental metaphysic is the same: atomised selves, who cannot be infringed upon by collective projects. The modern left recognises that for the self to be liberated, they have to be embedded within a social context in which their self-expression is affirmed. To this end, collective action is necessary, and proven to work in the success of the Civil Rights movement. Ironically enough, the Common Sense Conservative often appeals to the MLK Jr. attitude of the ‘content of character’ to resist identity politics. The disagreement between these two forces is not a philosophical one, but a pragmatic one – do we undergo collective action to liberate the self, or do we rely on an atomised individualistic approach which denies group differences?

These inherent parallels make nice-sounding hollow appeals to buzzwords necessary. To actually explicate a coherent philosophy would be to fundamentally challenge not just the desirability of things like free speech, but the real possibility of such a thing to begin with. No-one believes free speech means you can broadcast the position of all nuclear submarines, and this belief has to be justified somehow. Put simply, you’re not allowed to do this because it threatens the political order atop of which your right to free speech rests. The principle is simple then: you cannot extend your principles to those who would threaten their existence. Yet, when Novara Media, an outlet which calls consistently for deplatforming is itself deplatformed – the sycophants from GB News and UnHerd flock to fill the void, with Tom Harwood claiming they have a right to be heard.

What this underscores is a hesitance to actually give limits on rights and so-called freedoms, preferring instead to defer to whatever seems reasonable in the given circumstance. Consequently, the Common Sense Conservative often finds himself shaped by the social context he inhabits; these environments quickly become targets for Gramscian takeover and ensure that what qualifies for Common Sense tomorrow will be assuredly more left wing than Common Sense today.

An example of this emerges in the way we discuss positive discrimination, quotas, or diversity. Quite recently, Andrew Bridgen MP posted a photograph of him and his supporters at the 41 Club in Castle Donington. In response, he suffered anti-white racist abuse due to the fact his supporters were White. Among these responses, someone mentioned the only diversity in the room was the waiting staff – and it was this response one Common Sense Conservative took to highlight the ‘bigotry’ of the progressive opposition. For this individual, it was not at all noteworthy that a gathering of white people was apparently subject for abuse, but instead a passing comment about non-whites was the indicator of racism. Again, we see that the framing of the discussion is always limited by social context. It goes with the general flow of society to defend even the most minor form of prejudice towards non-whites, before defending overt prejudice towards whites – and so the latest iteration of Common Sense dictates that this must be where the opposition is mounted.

The argument that affirmative action, quotas, and diversity are actually bad for those they claim to help is 50 years old now. Thomas Sowell made it in its honest and earnest form in the 1970s, and since then conservatives have used it to defeat the left – on their own terms. What continues to go unaddressed is that the primary victims of affirmative action are not ethnic minorities, who lose their ability to provide for themselves by being given grants or get placed in educational facilities that have workloads they are mismatched for. The primary victim is the majority population which loses money to pay for these grants but do not benefit from them, and lose places they otherwise would have achieved in educational facilities.

Ultimately, these unexamined priors which are justified under the edifices of ‘Common Sense’ reveal an intellectual vacuum in the modern right. The only attempt to form an alliance between intellectualism and conservatism in recent memory was the Conservative Philosophy Group in 1974, restarted with the help of Sir Roger Scruton in 2013. One exchange highlights the differences between the traditional form of conservatism with its modern vacuous counterpart:

Edward Norman (then Dean of Peterhouse) had attempted to mount a Christian argument for nuclear weapons. The discussion moved on to “Western values”. Mrs Thatcher said (in effect) that Norman had shown that the Bomb was necessary for the defence of our values. Powell: “No, we do not fight for values. I would fight for this country even if it had a communist government.” Thatcher (it was just before the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands): “Nonsense, Enoch. If I send British troops abroad, it will be to defend our values.” “No, Prime Minister, values exist in a transcendental realm, beyond space and time. They can neither be fought for, nor destroyed.” Mrs Thatcher looked utterly baffled. She had just been presented with the difference between Toryism and American Republicanism.

In Thatcher, we see appeals to values with no underpinning of where they emerge from and their justification, and in Powell we see a world-view which justifies itself from the ground up. It’s no wonder that today we see Thatcher emblazoned all across conference, to the extent that one Common Sense Conservative even has a cut-out of her in her room. Thatcher represents the true beginning of the vacuous conservativism that reduces Political problems to technical ones, and exists to retroactively justify the decisions of the mercantile class. To this end, it is incapable of creating anything new, and so invokes its own previous iterations with new coats of paint to provide a veneer of consistency over an economic order which fundamentally requires constant flux.

The flux of modernity is only truly possible because of the aforementioned metaphysic that we are atomised selves, who contract or compete to create the social, Political, and economic orders in which we live. We can therefore not be infringed upon as individuals, but are reconfigurable units in these wider orders, and by virtue of our individual nature – have no right to dictate what these wider orders are, as this would be an infringement upon the individual.

Appeals to ‘common values’ will never work as long as this individualistic ontology is accepted; it offers no justification as to why these common values cannot be departed from at will. For this reason, it is necessary to invoke ‘Common Sense’ as the reason to remain within the common set of values. But of course, by the time you must invoke common sense, it’s hardly common any more. I’m yet to have an argument over the common sense notion that one ought to look both ways before crossing the road, but I’ve had plenty of arguments about the fact that men aren’t women. Truthfully, these beliefs need justification beyond appeals to common sense. The categories of men and women need to be defined not just in a taken-for-granted social manner, but in a metaphysical, biological, and philosophical manner. Only when these beliefs are deeply rooted and interconnected with not just the fabric of oneself, but of the fabric of reality itself, can people be driven to the depths of passion necessary to rebuff the challenges of the modern world. To that end, a right-wing intellectual vanguard is necessary to any movement which seeks to overturn the new orthodoxies of modernity.

Fact and Fortune: A Note on The Particular

Writing this article makes me feel guilty. Like a manic scientist hunched over a microscope, I am hunched over a keyboard, conducting research into pinpointing the unpinpointable. For decades, conservatives have disapprovingly commented on the widespread adoption of once-alternative socially liberal concepts and arrangements, lamenting the desacralization and deprivileging of more “traditional” outlooks. This is very much in step with classic political dynamics: Liberals will tell you “Yes”, Leftists will tell you “Yes, and more!”, and a conservative will tell you “No”. Whilst I generally agree with such disapproving commentary, I will not be contributing to it. Instead, I shall be addressing that which animates the conservative’s disapproval; stating what love is, rather than what is not, all while resisting its substitution with other concepts (pleasure, happiness, etc.) as has been done before. Consequently, I hope to form a fragment of a “moral-social vision” to which a conservative can forcefully say: “Yes”. Moreover, it should be prefaced that I do not care for contemporary fads, such as “making sense”.

Underpinning all human relationships lies an implicit and relative distinction between what is familiar and strange. Courtesy of the innate biological, geographical, and psychological limits of (for lack of a better term) the self, from birth to death most of humanity is a stranger; their existence is affirmed without personal interaction and their initial relation to the self is ambiguous. As proximity to the self transforms, so does the nature of the relationship – strangeness gradually fades away and familiarity increasingly emerges. However, whilst technically specific, the self is a mosaic; it is downstream from various approximations which give identity and demand obligation: the family, the local community, and the nation, all exist as approximations to what is familiar, stretching out towards the stranger.

In the most irremovable fundamental and primordial sense, the family and the self are the same, thus describing the family as a realm of the self, as opposed to what the self is, does not make sense. As such, the first approximation which exists beyond the self, the one more intimate and more familiar than the much wider community, as if it was Venus slotted between Mercury and Earth, is that of the Particular.

The Individual and The Particular are not totally distinct. Whilst technically different, a Particular cannot deny its necessary origins as an Individual, that is to say: certain residual characteristics of an Individual will remain within the Particular even when an Individual becomes Particular. The key commonality between the Individual and the Particular is that both are necessarily unique and singular; they both refer to one. The fundamental difference between the Individual and the Particular is therefore twofold: the nature of [the] reference, and the nature of [the] one.

The Individual One is strictly numerical, it concerns isolated quantity amid implied greater quantity. Conversely, The Particular One is non-quantifiable. It is not perceived mathematically, but in a qualitative and subjective manner; the self-realised reality that there can be no concept of greater quantity when concerned with the existence of something radically specific. However, bound up in the nature of [the] One is how it is referred to. Unlike the Individual, the Particular is realised by a person; it emerges, rising above individualised mass. In this regard, whilst the Individual is an impersonal concept, the Particular is deeply personal.

Facts are the unbending exoskeleton of reality. Hardly negative, they are nevertheless mere matters of being, they are acknowledged by all for the sake of all; they are granted and therefore taken for granted. On the other hand, Fortunes emerge from an incomprehensible conglomerate of probabilities. More than simply being, the total feasibility of Fortune’s non-existence gives it subjective value; to exist as it does makes it remarkable, as if it were a roaring fire in a field of snow. As such, the “impersonally perceived quantifiable” Individual constitutes an existential Fact, whilst the “personally perceived non-quantifiable” Particular constitutes an existential Fortune.

Like every conceivable Fortune, it is discovered through action. Ways colliding through distinct affirmations of life as part of civilised existence, the Particular incrementally emerges into view. The glamourous unthinking of the animal, lurking beneath such civilised folk, smoothens rough edges into idiosyncrasies. It is only during this way-splicing journey that one is eventually obstructed by the wretched bluntness of Fact. The Particular is particular. Made radically specific by intersections of time and space, The Particular is temporary. Mortality, granted and therefore taken for granted, is never acknowledged for its wretchedness until compared to the shining novelty of Fortune. Icarus, made ecstatic by the heights to which his wings could take him, is blighted by the unmissable sun and is reacquainted with reality. Realisation of temporality is the highest realisation of the Particular and thus the undoing of the Self’s tranquillity. It is because of this that all love is bittersweet. A volatile spirit, it wrestles to be total, to be free of its own contradictions; it is humanity’s purest extremity.

Unfortunately, contemporary notions of love have come to be dominated by material transaction, in which material things are exchanged for something in return all while being divorced from direction, tailored only to generalised individual mass rather than the Particular, Regardless of whether material transaction is a consciously cynical effort or just well-meaning naivete, it should be considered a perversion of the material’s true role of expression: the act of turning the immaterial into something material, internal motion into an external display. Even if both are in want, the former deals in expectations whilst the latter deals in hope. Consequently, given the ritualistic importance, just as one who wants to receive must be prepared to give, where one does not wish to give, one must refuse.

Far from pedanticism, there must be immovable details, actions, and sentiments which are confined to the realm of The Particular. If it lacks these, there is no such thing as a distinct romantic approximation; the Particular would cease to be particular at all. Hence why a private realm, knitted together by a veneer of secrecy and the consequent warding off transgressions is not only required, but the very essence of love. The contradiction of this private realm is that it can only be fully secured through public recognition; signifying that there are boundaries which those inside and outside cannot bend if the realm is to exist at all. It is the inability to reconcile this private realm with the world that lies beyond, especially the family and community, that produces the Romeo and Juliet tragedies we all intuitively understand.

At bottom level, these perversions stem from having been confronted by temporality which afflicts us all. Like madmen, they hurry to evade the inevitable. Impending fates, they make frenzied decisions, no sober consideration of what would do them better. Attempting to hoard the whole of humanity in your heart, being subject to the neurotic clamouring for more, made unawares that all will have so much less; you less of them, and them less of you. Just as a nation that attempts to contain the world within its borders does not enrich itself, and consequently makes a world in which the nation no longer exists.

Nobody makes a conscious decision to love, they simply do (on its own, it is Fact which precedes the Fortune of the Particular). It is those deluded folks who choose to act against love that engage in a conscious decision. Like building a dam to obstruct a coursing stream, it is a crude denial of motion. It is because of this motion that the emergence of the Particular cannot be reduced to a meticulous list of preferences. The mechanised procedure of romance has been attacked as a neutralising reconfiguration of love, implying it to be an organic development instead – which it is. If an organic something has stagnated it is either dead or on the verge of death – making compatibility the project, rather than the immediate gratification of love. Just as a flower’s idea of itself animates the contortions of its growth, giving clear form to lofty substance, the idea of two-minded unity is the grand project to which love draws its form and loyally commits its efforts. Unlike the machine which facilitates fleeting relations and heavy-handed intimacy, the Becoming force of love, that which sought to forge beyond the self and in the direction of the Particular, if found to be requited by life’s chances, necessarily reorients itself to go beyond life itself.

The afterlife exists as a Fact. Calling this afterlife “death” makes no difference. There are two certainties: our certain uncertainty of the exact nature of the afterlife and our absolute certainty of our heading there. Whether it’s the minds of men, eternal darkness, or literal new life, it matters not; there is a flipside to this state which gives this life so much meaning. The totality of the Particular and the fullness of heart it provides, ever-driving the two-minded unity, ushers the secret realm into existence, giving us a place not only within explicit life, but within implicit afterlife. Two radically specific souls, becoming one radically specific unit, find themselves undivided by death.

The first approximation, the most intimate and warmest flame, with correspondence to be earnestly followed up or to be dutifully waited on, mends the disjointed nature of life and afterlife. By forging a chain that can never be broken, mere existence is transformed into terrain traversing adventure. The ability to stare into the reaper’s eyes as if they were the eyes of the Particular; that is the essence of love. Never will the strange feel so familiar.

The possible booster/lockdown trade-off

At the time of writing, the UK is facing a sharp rise in cases of the novel Omicron variant. As a result, after a relatively normal summer and autumn, the government has now enacted ‘Plan B’, a series of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) including mandated mask wearing as well as work-from-home and vaccine passport recommendations, all intended to slow the virus’ spread. Further, despite having previously denied having any intention of doing so, it now appears to be floating the possibility of a third national lockdown or lockdown lite, limiting indoor dining (in winter…) and socialising. Amidst this, the government’s messaging continues to be that Omicron’s defeat lies in widespread uptake of the covid vaccine’s booster dose, which is not really surprising as we had previously been warned that the emergence of new variants would likely require cycles of booster jabs. This may not seem like terribly controversial advice in a country like the UK where, up until now, vaccine acceptance has been high. However, it is naïve to assume that all those who accept the jab do so for the same reasons. And, by that token, short-sighted not to consider the negative impact that another lockdown (or indeed the mere threat of one) could have on future levels of vaccine acceptance amongst some.

Given the toxicity of vaccine discussions (consider, the boogieman figure of the antivaxxer as the epitome of wilful ignorance and callousness, even before covid), the vaccine-hesitant report being unlikely to share their reservations with vaccine-acceptant peers for fear of encountering derision or scorn. As a result, vaccine accepters seldom have to engage with anything other than a David Icke-esque caricature of vaccine hesitancy. This obscures how, far from belonging to separate realms of ‘reason and science’ and ‘irrationality and conspiracy’, vaccine attitudes exist on the same spectrum, tipped by out-and-out refusal and full acceptance, and filled in by a gamut of vaccine hesitancies. Similarly, the binary outcomes of a vaccine decision (either you get jabbed or you don’t) obscure how people with different degrees of hesitancy will opt to receive covid vaccine but, given their differing stances, may respond differently to future policy changes regarding boosters and lockdowns.

Through a study based on a series of online surveys March 15th and April 22nd, 2021, academics from Swansea University identified at least two sorts of attitude amongst accepters of the covid vaccination. Being vaccine-accepters, both had received at least one dose of a covid vaccination or indicated their intentions to do so when it was offered to them.

However, whereas ‘full-accepters’ experienced few qualms about their decision to get jabbed, often just seeing it as an extension of a well-established social-norm, ‘accept-but-unsure’ accepters were more ambivalent, thus flirting with vaccine hesitancy. Though they did accept a jab (or said they would when it came to it), they did so with some concerns about its safety and effectiveness.

In explaining their eventual decision to accept the vaccine, they emphasised a trust in science (“I was a bit suspicious… but the science today compared to years ago is outstanding isn’t it?”) and sense that, whatever their reservations, the vaccine was in some way necessary to allow for a return to ‘normality’. Vaccination was seen as “the only way forwards, to get on with our lives”. Anecdotally, I find that this certainly chimes with my experience of social media last spring when Twitter was briefly aflood with clips of fully vaccinated Israelis rediscovering the pleasures of legal public-gatherings and indoor dining, and promising a happier, freer summer than the last. More academically, surveys carried out by the ONS this

September found that 65% of previously hesitant accepters gave a desire for restrictions to ease and life to return to normal as one of their motivations for getting jabbed (interestingly, only 21% gave potential vaccine passports as one of theirs but this is another story).

Importantly, this recognition of the vaccine’s necessary role in our return to normality often involved a recognition that this was not a ‘one off’, that is, that there would in all likelihood be cycles of boosters in response to novel variants of the virus. It was largely recognised that as these emerged, we would need to continue receiving jabs to protect normal life and stave off life-destroying NPIs like lockdown.