Is it Possible to Live Without a Computer of Any Kind?

This article was originally published on 19th May 2021.

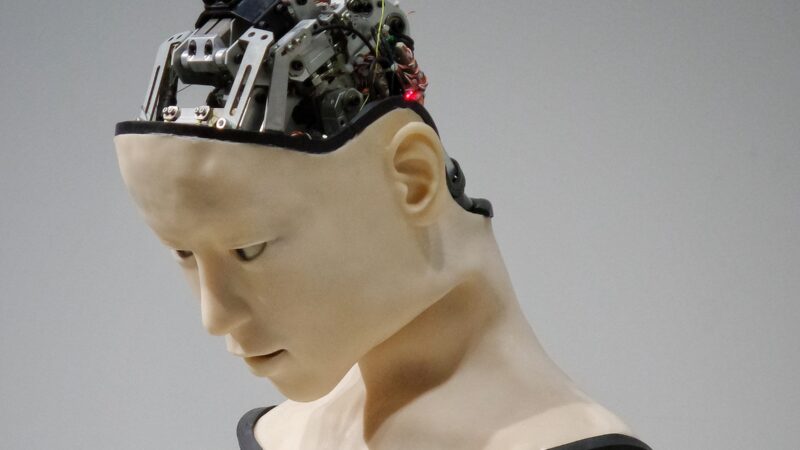

I am absolutely sick to death of computers. The blue light of a screen wakes me up in the morning, I stare at another computer on my desk for hours every day, I keep one in my pocket all the time and that familiar too-bright glow is the last thing I see before I close my eyes at night. Lockdown undoubtedly made the problem much, much worse. Last year, a nasty thought occurred to me: it might be the case that the majority of my memories for several months were synthetic. Most of the sights and sounds I’d experienced for a long time had been simulated – audio resonating out of a tinny phone speaker or video beamed into my eyes by a screen. Obviously I knew that my conscious brain could tell the difference between media and real life, but I began to wonder whether I could be so sure about my subconscious. In short, I began to suspect that I was going insane.

So, I asked myself if it was possible to live in the modern world without a computer of any kind – no smartphone, no laptop, and no TV (which I’m sure has a computer in it somewhere). Of course, it’s possible to survive without a computer, provided that you have an income independent of one, but that wasn’t really the question. The question was whether it’s possible to live a full life in a developed country without one.

Right away, upon getting rid of my computers, my social life ground to a halt. Unable to go to the pub or a club, my phone allowed me to feel like I was still at least on the periphery of my friends lives while they were all miles away. This was hellish, but I realised that it was the real state of my life – my phone acted as a pacifier and my friendships were holograms. No longer built on the foundation of experiences shared on a regular basis, social media was a way for me to freeze-dry my friendships – preserve them so that they could be revived at a later date. With lockdown over though, this becomes less necessary. They can be reheated and my social life can be taken off digital life support. I would lose contact with some people but, as I said, these would only be those friendships kept perpetually in suspended animation.

These days large parts of education, too, take place online. It’s not uncommon now in universities, colleges and secondary schools for work and timetables to be found online or for information to be sent to pupils via internal email networks. Remote education during lockdown was no doubt made easier by the considerable infrastructure already in place.

Then there’s the question of music. No computers would mean a life lived in serene quiet; travelling and working without background sound to hum or tap one’s foot to. An inconvenience, maybe, but perhaps not altogether a negative one. Sir Roger Scruton spoke about the intrusion of mass-produced music into everyday life. Computer-produced tunes are played at a low level in shopping centres and restaurants, replacing the ambient hum and chatter of human life with banal pop music. Scruton believed that the proper role of music was to exalt life – to enhance and make clear our most heartfelt emotions. Music today, though, is designed to distract from the dullness of everyday life or paper over awkward silences at social events. He went so far as to say that pop consumption had an effect on the musical ear comparable to that of pornography on sex.

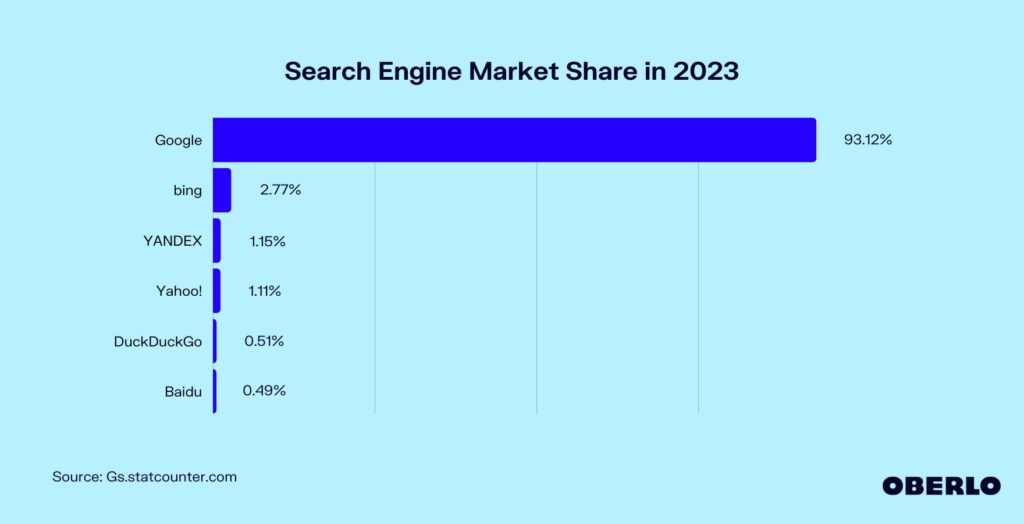

The largest barrier, however, is the use of the internet for work. Many companies use online services to organise things like shift rotas, pay and holidays and the entire professional world made the switch to email decades ago. How feasible is it to opt out of this? Short of becoming extremely skilled at something for which there is both very little supply and very high demand, and then working for a band of eccentrics willing to accommodate my niche lifestyle, I think it would be more or less impossible. Losing the computer would mean kissing the possibility of a career goodbye.

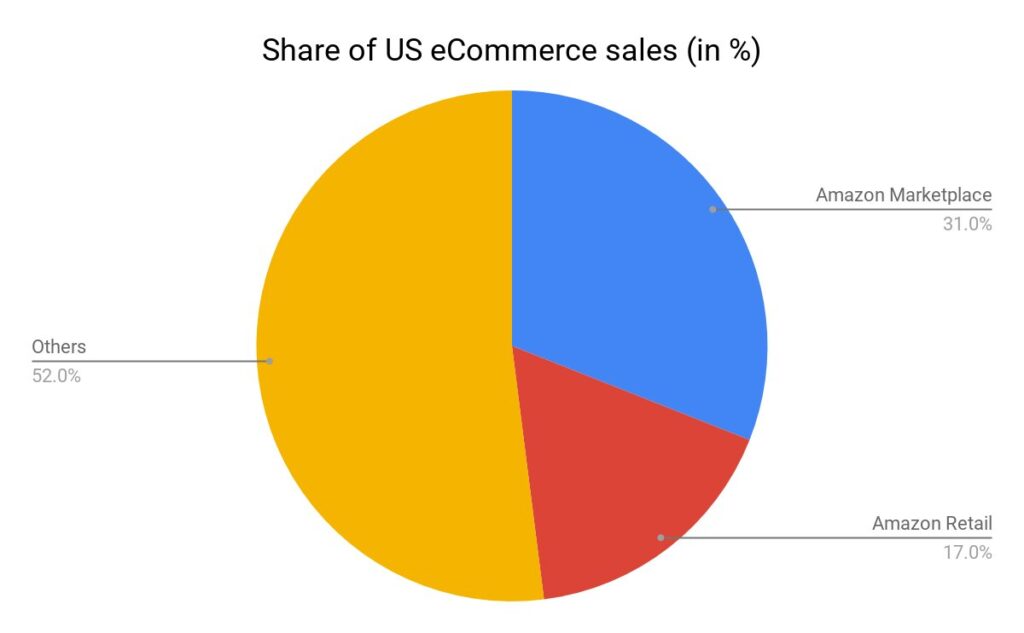

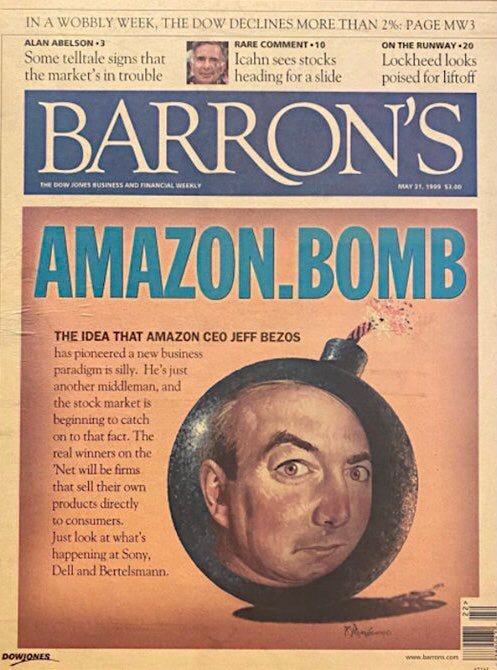

Lockdown has also sped up the erosion of physical infrastructure required to live life offline as well as accelerated our transformation into a ‘cashless society’. On average, 50 bank branches have closed every month since January 2015, with over 1000 branch closures across the country in the last year alone. It also seems to have wiped away the last remaining businesses that didn’t accept card payments. The high street, already kicking against the current for years, is presently being kept alive by Rishi Sunak’s magic money tree while Amazon records its best quarter for profits ever. It’s no mystery to anyone which way history will go.

I’m lucky that my parents were always instinctively suspicious of ‘screens’. I didn’t get a smartphone until a good way into secondary school and I got my first – and only – games console at the age of 16. I keenly remember getting a laptop for my birthday. I think my parents gave it to me in the hopes that I would become some kind of computing or coding genius – instead, I just played a lot of Sid Meiers Civilisation III. My dad would remind me that nothing on my computer was real, but that didn’t stop me getting addicted to games. If it wasn’t for my parents’ strong interventions I would likely have developed a serious problem – sucked into the matrix and doomed to spend my youth in my bedroom with the blinds down.

All year this year I have wrestled with my media addiction but been unable to throw it off. I told my friends that I was taking a break from social media, I deactivated my Twitter account, I physically hid my phone from myself under my bed, and yet here I am, writing this on my laptop for an online publication. When I got rid of my phone I turned to my computer to fill the time. When I realised that the computer was no better I tore myself from it too… and spent more time watching TV. I tried reading – and made some progress – but the allure of instant reward always pulled me back.

I’m not a completely helpless creature, though. On several occasions I cast my digital shackles into the pit, only to find that I needed internet access for business that was more important than my luddite hissy-fit. Once I opened the computer up for business, it was only a matter of time before I would be guiltily watching Netflix and checking my phone again. It’s too easy – I know all the shortcuts. I can be on my favourite time-absorbing website at any time in three or four keystrokes. Besides, getting rid of my devices meant losing contact with my friends (with whom contact was thin on the ground already). Unplugging meant really facing the horrific isolation of lockdown without dummy entertainment devices to distract me. I lasted a month, once. So determined was I to live in the 17th century that I went a good few weeks navigating my house and reading late at night by candlelight rather than turning on those hated LEDs.

And yet, the digital world is tightening around us all the time. Year on year, relics of our past are replaced with internet-enabled gadgets connected to a worldwide spider web of content that has us wrapped up like flies. Whenever I’ve mentioned this I’ve been met with derision and scorn and told to live my life in the woods. I don’t want to live alone in the woods – I want to live a happy and full life; the kind of life that everyone lived just fine until about the ’90s. I’m sick of the whirr and whine of my laptop, of my nerves being raw from overuse, of always keeping one ear open for a ‘ping ’or a ‘pop’ from my phone, and of the days lost mindlessly flicking from one app to the other. Computers have drastically changed the rhythm of life itself. Things used to take certain amounts of time and so they used to take place at certain hours of the day. They were impacted by things like distance and the weather. Now, so much can occur instantaneously irrespective of time or distance and independent from the physical world entirely. Put simply, less and less of life today takes place in real life.

The world of computers is all I’ve ever known and yet I find myself desperately clawing at the walls for a way out. It’s crazy to think that something so complex and expensive – a marvel of human engineering – can become so necessary in just a few decades. If I can’t get rid of my computers I’ll have to learn to diminish their roles in my life as best I can. This is easier said than done, though; as the digital revolution marches on and more and more of life is moved online, the digital demons I am struggling to keep at arm’s length grow bigger and hungrier.

I’m under no illusions that it’s possible to turn back the tide. Unfortunately the digital revolution, like the industrial and agricultural revolutions before it, will trade individual quality of life for collective power. As agricultural societies swallowed up hunter gatherers one by one before themselves being crushed by industrial societies, so those who would cling to an analogue way of life will find themselves overmatched, outcompeted and overwhelmed. Regardless, I will continue with my desperate, rearguard fight against history the same way the English romantics struggled against industrialisation. Hopeless my cause is, yes, but it’s beautiful all the same.