Human rights are controversial. They probably shouldn’t be, being instead something we should all be able to rally around as the bare minimum we can do to protect our fellow man from the harms that could be inflicted upon them by the cruel. But that is not the case. As with most other things, human rights have been co-opted by both sides of the debate to feed the war-machines of angst. The Rwanda immigration policy is the latest battleground, but it won’t be the last. This will never fully be resolved, but a new British Bill of Rights will go a long way.

Personally I have never been a fan of a codified set of rights. I am not sure we need to be told by a specific document that we have the right to life. It should transcend a piece of paper into our way of being. We have, being a civilised people here in the United Kingdom, worked it out on our own, with many of the rights we have anticipated in the European Convention on Human Rights.

But that is often forgotten due to this constitution-style system. People seem to forget that these rights are as human to us as breathing, and that they didn’t just burst into existence upon drafting. The only time this happened was at Mount Sinai, and even then, I would contend that most of them were already held within the hearts and minds of the assembled peoples who heard them. Codified sets of rights take on a mythical status, used by those of a more puritanical bent to suggest that without said list, we would all fall the next day into some purge-like hellscape, acting with horrendous disregard for all others.

However, just as nature abhors a vacuum, the cogs of the judicial system thrive on vagaries. There will always be room for interpretation (especially, somewhat ironically, with things so fundamental), so it is the lesser of the evils to have these rights written down for all to see, so our intent is clear. There will always be lacunas to fill, but you can rest easy knowing it will be by like-minded individuals, attuned to the clear direction of the people they will impact, understanding their tradition, position, and direction.

But that isn’t the case as things stand, and it is where most of the current controversy around human rights actually sits. As things stand, we have a scenario where the interpretation of these fundamental items, these things so personal to a people, is conducted supranational, by a group not attuned to how these rights are embedded within us, and how we in the UK wish them to be used. It sows division within our country to have these matters decided for us, outside of our own structures that we have built to govern and protect each other.

Of course, we did sign up, there was originally consent for this position, but we are a long way now from the post-war mindset that led to the ECHR being created. We have moved on. Not to the extent that we wish to abandon any of the rights themselves (no matter what certain commentators would have you believe), but in terms of how we wish the grey to be made black and white.

The best thing to do, therefore, is to withdraw from the ECHR, and recreate the convention as an Act of Parliament. It shouldn’t be too difficult, given how involved in the drafting we were in the first place. This glorious legislation should then be given the fanfare and patriotic name it deserves. And in doing so we will free ourselves from the shackles of the current situation, while still providing a beacon of hope for all to rally around.

Each side should be happy with the result.

As the precious document will still exist, the ‘frothers-in-chief’ will be content that the UK won’t slip into lawlessness overnight, while the rest of us can be happy that we will be in the position where any interpretation is done within our own judicial structure, using our thought processes, aligned to our own (lower order, but still important) values.

There will still be much need to call on the judiciary to interpret our fundamental rights, and there will still be cases that cause division. But we will be able to at least point to our own shared national heritage, and our wonderful common law, as the reasoning for these decisions. They will have been made by us, for us, to protect us. Just like our human rights.

You Might also like

-

Atatürk: A Legacy Under Threat

The founders of countries occupy a unique position within modern society. They are often viewed either as heroic and mythical figures or deeply problematic by today’s standards – take the obvious examples of George Washington. Long-held up by all Americans as a man unrivalled in his courage and military strategy, he is now a figure of vilification by leftists, who are eager to point out his ownership of slaves.

Whilst many such figures face similar shaming nowadays, none are suffering complete erasure from their own society. That is the fate currently facing Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, whose era-defining liberal reforms and state secularism now pose a threat to Turkey’s authoritarian president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

To understand the magnitude of Atatürk’s legacy, we must understand his ascent from soldier to president. For that, we must go back to the end of World War One, and Turkey’s founding.

The Ottoman Empire officially ended hostilities with the Allied Powers via the Armistice of Mudros (1918), which amongst other things, completely demobilised the Ottoman army. Following this, British, French, Italian and Greek forces arrived in and occupied Constantinople, the Empire’s capital. Thus began the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire: having existed since 1299, the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) ceded large amounts of territory to the occupying nations, primarily being between France and Great Britain.

Enter Mustafa Kemal, known years later as Atatürk. An Ottoman Major General and fervent anti-monarchist, he and his revolutionary organisation (the Committee of Union and Progress) were greatly angered by Sèvres, which partitioned portions of Anatolia, a peninsula that makes up the majority of modern-day Turkey. In response, they formed a revolutionary government in Ankara, led by Kemal.

Thus, the Turkish National Movement fought a 4-year long war against the invaders, eventually pushing back the Greeks in the West, Armenians in the East and French in the South. Following a threat by Kemal to invade Constantinople, the Allies agreed to peace, with the Treaty of Kars (1921) establishing borders, and Lausanne (1923) officially settling the conflict. Finally free from fighting, Turkey declared itself a republic on 29 October 1923, with Mustafa Kemal as president.

His rule of Turkey began with a radically different set of ideological principles to the Ottoman Empire – life under a Sultan had been overtly religious, socially conservative and multi-ethnic. By contrast, Kemalism was best represented by the Six Arrows: Republicanism, Populism, Nationalism, Laicism, Statism and Reformism. Let’s consider the four most significant.

We’ll begin with Laicism. Believing Islam’s presence in society to have been impeding national progress, Atatürk set about fundamentally changing the role religion played both politically and societally. The Caliph, who was believed to be the spiritual successor to the Prophet Muhammad, was deposed. In their place came the office of the Directorate of Religious Affairs, or Diyanet – through its control of all Turkey’s mosques and religious education, it ensured Islam’s subservience to the State.

Under a new penal code, all religious schools and courts were closed, and the wearing of headscarves was banned for public workers. However, the real nail in the coffin came in 1928: that was when an amendment to the Constitution removed the provision declaring that the “Religion of the State is Islam”.

Moving onto Nationalism. With its roots in the social contract theories of thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Kemalist nationalism defined the social contract as its “highest ideal” following the Empire’s collapse – a key example of the failures of a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural state.

The 1930s saw the Kemalist definition of nationality integrated into the Constitution, legally defining every citizen as a Turk, regardless of religion or ethnicity. Despite this however, Atatürk fiercely pursed a policy of forced cultural conformity (Turkification), similar to that of the Russian Tsars in the previous century. Both regimes had the same aim – the creation and survival of a homogenous and unified country. As such, non-Turks were pressured into speaking Turkish publicly, and those with minority surnames had to change, to ‘Turkify’ them.

Now Reformism. A staunch believer in both education and equal opportunity, Atatürk made primary education free and compulsory, for both boys and girls. Alongside this came the opening of thousands of new schools across the country. Their results are undeniable: between 1923 – 38, the number of students attending primary school increased by 224%, and 12.5 times for middle school.

Staying true to his identity as an equal opportunist, Atatürk enacted monumentally progressive reforms in the area of women’s rights. For example, 1926 saw a new civil code, and with it came equal rights for women concerning inheritance and divorce. In many of these gender reforms, Turkey was well-ahead of other Western nations: Turkish women gained the vote in 1930, followed by universal suffrage in 1934. By comparison, France passed universal suffrage in 1945, Canada in 1960 and Australia in 1967. Fundamentally, Atatürk didn’t see Turkey truly modernising whilst Ottoman gender segregation persisted

Lastly, let’s look at Statism. As both president and the leader of the People’s Republican Party, Atatürk was essentially unquestioned in his control of the State. However, despite his dictatorial tendencies (primarily purging political enemies), he was firmly opposed to dynastic rule, like had been the case with the Ottomans.

But under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, all of this could soon be gone.

Having been a high-profile political figure for 20 years, Erdoğan has cultivated a positive image domestically, one focused on his support for public religion and Turkish nationalism, whilst internationally, he’s received far more negative attention focused on his growing authoritarian behaviour. Regarded widely by historians as the very antithesis of Atatürk, Erdoğan’s pushback against state secularism is perhaps the most significant attack on the founder’s legacy.

This has been most clearly displayed within the education system. 2017 saw a radical shift in school curriculums across Turkey, with references to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution being greatly reduced. Meanwhile, the number of religious schools has increased exponentially, promoting Erdoğan’s professed goal of raising a “pious generation of Turks”. Additionally, the Diyanet under Erdoğan has seen a huge increase in its budget, and with the launch of Diyanet TV in 2012, has spread Quranic education to early ages and boarding schools.

The State has roles to play in society but depriving schoolchildren of vital scientific information and funding religious indoctrination is beyond outrageous: Soner Cagaptay, author of The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey, referred to the changes as: “a revolution to alter public education to assure that a conservative, religious view of the world prevails”.

There are other warning signs more broadly, however. The past 20 years have seen the headscarf make a gradual reappearance back into Turkish life, with Erdoğan having first campaigned on the issue back in 2007, during his first run for the presidency. Furthermore, Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), with its strong base of support amongst extremely orthodox Muslims, has faced repeated accusations of being an Islamist party – as per the constitution, no party can “claim that it represents a form of religious belief”.

Turkish women, despite being granted legal equality by Atatürk, remain the regular victims of sexual harassment, employment discrimination and honour killings. Seemingly intent on destroying all the positive achievements of the founder, Erdoğan withdrew from the Istanbul Convention (which forces parties to investigate, punish and crackdown on violence against women) in March 2021.

All of these reversals of Atatürk’s policies reflect the larger-scale attempt to delete him from Turkey’s history. His image is now a rarity in school textbooks, at national events, and on statues; his role in Turkey’s founding has been criminally downplayed.

President Erdoğan presents an unambiguous threat to the freedoms of the Turkish people, through both his ultra-Islamic policies and authoritarian manner of governance. Unlike Atatürk, Erdoğan seemingly has no problems with ruling as an immortal dictator, and would undoubtedly love to establish a family dynasty. With no one willing to challenge him, he appears to be dismantling Atatürk’s reforms one law at a time, reducing the once-mythical Six Arrows of Kemalism down to a footnote in textbooks.

A man often absent from the school curriculums of Western history departments, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk proved one of the most consequential leaders in both Turkish history, and the 20th Century. A radical and a revolutionary he may have been, but it was largely down to him that the Turkish people received a recognised nation-state, in which state secularism, high-quality education and equal civil rights were the norm.

In our modern world, so many of our national figures now face open vilification from the public and politicians alike. But for Turkey, future generations may grow up not even knowing the name or face of their George Washington. Whilst several political parties and civil society groups are pushing back against this anti-Atatürk agenda, the sheer determination displayed by Erdoğan shows how far Turks must yet go to preserve the founder’s legacy.

Post Views: 830 -

Switzerland-on-Sea: Britain in a Multipolar World

“There are decades when nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happen.”

This quote is (dubiously) attributed to Lenin but I like it nonetheless as it appropriately captures the times we live in.

That’s not to say nothing’s happened for decades, far from it. The years following the last financial crisis have seen seismic changes across Western societies and the wider world. The Eurozone crisis, Middle East civil wars, tsunamis of illegal migration, Ukraine torn in two, Brexit, Trump, plummeting birth rates, economic stagnation, and the explosion in political corruption that resulted in the criminal psychological operation that was the pandemic and continues through war and ‘green’ policy. The weeks following Russia’s so-called ‘Special Military Operation’ felt like weeks when decades happened. Yet something about these last few weeks – with a war (even more senseless than the intra-Slavic trench slaughter) threatening to suck in the whole world – feels like we have moved into an accelerated phase of global change.

This is a familiar motif of history. Decades of failed rebellion against the Tsars eventually led to the February and October Revolutions. Newly educated generations in Africa and Asia quickly used their power and influence to kick out their colonial masters. The ticking time bomb of financialisation that started in the 1980s didn’t explode until decades later. Likewise, the absolute failure of decades of collective Western foreign policy, as dictated by the U.S. via NATO and other organisations, has now started to show some of its very worst consequences.

Never in living memory have we as a nation been more ignorant about international relations and had less perspective about our place in the world. The dumbing down of our foreign policy debate (and its incorporation into the ‘culture war’) is a far cry from even the Brexit era, when millions of Brits followed the machinations of our foreign entanglements with interest, engaging in relatively honest debates about what they should be and where our national interest lies.

In 2014, one of Nigel Farage’s major criticisms of Brussels was its ‘militant’, ‘expansionist’ and ‘absolutely stupid’ foreign policy. In a debate with then deputy PM Nick Clegg, he said the Lib Dems represented hatred and extremism by ‘constantly screaming out for us to go to war’, adding he was ‘sick to death of this country getting involved in foreign wars’. Farage said the EU had ‘blood on its hands’ for encouraging the Maidan coup in Ukraine, as well as ‘bombing Libya’ into becoming an ‘ungovernable breeding ground of terrorism’, and arming rebel militias in Syria ‘because they didn’t like Assad, despite being infiltrated by extremists’. How prescient.

Now, this type of critical discourse is almost entirely absent from our political spectrum and media. There has been a chilling uniformity of message on the blood-soaked meatgrinder that is Ukraine – more weapons, more money, Putin is Hitler, Slava Ukrainii. A feeling engineered by the unquestioned, key narrative of an independent democracy facing an unprovoked invasion (a narrative which is demonstrably untrue). With the latest conflict in the Middle East, the right has fallen behind Israel in complete lockstep, calling for deportations and arrests for speech expression, and taking a harder line than many Israelis. The left, barren of a moral compass and mentally ill, has resorted to second-hand asabiyyah and strange attempts to pinkwash Hamas, joined on the streets by the usually out-of-sight 3rd-gen Islamist yoof. It’s an ugly sight.

What is missing from all of this is Britain. What are Britain’s interests in this rapidly deteriorating international system? No one, it seems, has bothered to ask. This is a problem. The points I have made so far often provoke accusations of ‘isolationism’, and not realising that a stable globe is one of our most immediate needs. That is not in any doubt. What is highly questionable is the way we go about promoting that stability, as it clearly hasn’t been working.

In the West we still believe that we make alliances and enemies based on good and evil, or ‘shared values’, and we think this is the same as our interests. Whether ‘humanitarian intervention’ or ‘supporting democracy’, the arguments made against the abuses of certain countries must be applied equally or not applied at all, otherwise it is not a reason for action, but a pretext. The onus should be on those who argue for action, not on those who argue for not getting involved, to make their case. Especially with the mountain of evidence that outside intervention, militarily or otherwise, almost always makes countries worse.

A good case is made for this in A Foreign Policy of Freedom: Peace, Commerce, and Honest Friendship, a compilation of Ron Paul’s speeches to Congress over 30 years, each containing dozens of examples of foreign interventions and interference being counterproductive to U.S. interests. Yes, other countries are very often not nice places to live and have disagreeable cultures, but the best way to deal with them is engaging economically and not getting involved in their domestic politics. Our strategy has been to bomb countries and organise armed coups. Importing millions of people from these same countries has also turned out to be a bad idea.

So, if we step back from ‘policing’ the world, how then would we be able to ensure a stable international environment? Like charity, order starts at home. We preach to the world about how to run their societies when we have so many problems of our own. We defend the sanctity of others’ borders and sovereignty while making a mockery of our own. We accuse our selected ‘enemies’ of criminality, propaganda, and deception when we do a pretty good job of all that ourselves. In other words, we don’t speak softly and carry a big stick, we bark and scream. ‘Be change you want to see in the world’ – another made up quote attributed to a world leader – is a motivational meme but it should be an axiom of a ‘moral’ foreign policy if that’s what we want.

The hegemony of the West is coming to an end and there are no two ways about it. According to comedian turned IR expert Konstantin Kisin, ‘Multipolarity requires a decade-long process of the unipolarity disintegrating. And will inevitably result in an eventual return to unipolarity with a different hegemon. This is why this process should be opposed with everything we have’. I hate to break it to him, but that disintegration has been happening for a long time already and is not something that we can now ‘oppose’ with centre-Right politicians. Their neoliberalism is why we are so exposed, having exported our manufacturing and imported the world’s poor, while crippling ourselves with manmade social and economic breakdown.

The second point made by Kisin is interesting to dissect. Is it inevitable that the West ceasing to be the dominating ‘pole’ of international power will result in another power taking its place? No, it’s not. Unipolarity is a freak of human history. The positions of the U.S. and USSR after the Second World War created the bipolar world, and their respective empires. When the Cold War ended, the U.S. subsumed communist remnants becoming the pole of global power by default. It was the end of history, and liberal democracy was the endpoint of all human social evolution and the final form of government. On this basis the position of hegemon was squandered and abused.

The reality is that most of history has been a multipolar world and as we return to that state, it will not be peaceful or pretty. The man who coined the ‘Big stick philosophy’, Teddy Roosevelt, described his style of foreign policy as ‘the exercise of intelligent forethought and of decisive action sufficiently far in advance of any likely crisis’. To apply that to Britain today would mean gearing up to be a Switzerland-on-Sea; a discerning, independent, and sovereign nation.

When it comes to defence, Switzerland is (like the UK) blessed with fortunate geography and a long military tradition. Unlike the UK, it is not in NATO, it conscripts its young men, invests in its defence infrastructure, and does not take part in foreign wars. It is also a natural home for mediating and resolving international disputes, trusted by most countries around the world.

This strategic neutrality seems to work quite well for the Swiss and they do this while still aligning with the U.S. They even enjoy a boost in arms sales as other neutral countries prefer to buy Swiss weapons. Would Western civilisation collapse and the world be taken over by an Axis of Evil if the UK also left NATO, rebuilt its army, and took part in peacekeeping missions instead of wars? Probably not (If it collapses it will be for reasons of our own making). It is accepted as fact that we must dominate the world to protect ourselves from it, when in reality our attempts to do so have created the fragile state of affairs that exist today.

The fundamental mistake we make is being so certain that other countries will think and behave exactly like us. China is an ancient civilisation-state that has shown limited expansionist tendencies over many centuries. The last time Iran invaded a country was in the mid-18th century. Russia is psychologically bound by its size, geography, and history to be obsessed with feeling secure. These complicated civilisations have all been UK allies at various points during the 20th century and there is no reason why we can’t deal with them as unpleasant neighbours as opposed to mortal enemies. Unfortunately, our entire discourse ties us to the fate of the dying American empire. By taking on others’ enemies we expose ourselves to becoming targets.

Today in Britain, unchecked thousands of fighting-age purposeless men from the most turbulent, radical and traumatised parts of the world, are entering the country illegally via fleets of boats, the state seemingly powerless to stop it happening. Some would call that an invasion. Meanwhile, Tel Aviv has become the new Kiev as Prime Ministers old and new rush to get involved helping another country. Despite our politicians saying otherwise, the claim is always that they are there to create an outcome and environment that is in the UK’s interests. Well at the very least that would entail calling for a ceasefire, and at most it would mean pushing for a comprehensive political settlement. Trying to avoid a new wave of refugees, an oil price crisis and global recession would also be in our interest. There is no sign of this on Sunak or Johnson’s agenda, but there is a lot of talk about ‘finishing the job’, sticking to the narrative and facing down Iran and its proxies – the stuff of wet dreams for many a lobbyist in Washington DC.

It may be comforting to buy into the expertly packaged narratives being put out about this latest conflict, but some of us have seen this film before, and it doesn’t end well. In fact, it ends up in situations like Syria, where Hezbollah ends up defending the world’s most ancient Christian communities while Israel supports ISIS. It ends with the Jewish President of Ukraine overseeing neo-Nazi brigades fighting against Muslim and Buddhist soldiers over derelict villages. Clearly, the world is a complicated place. We used to know this. When will we give up our simple, black-and-white way of looking at it? When will we stop falling for the simplistic narratives fed to us?

Why should we have to listen to the arguments made about supporting a side in some conflicts, but not others? We are not asked to choose between supporting Azerbaijan or Armenia – because the media hasn’t told us to get angry about that. We are not asked to condemn Pakistan for expelling hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees – a humanitarian catastrophe in the making – because the media hasn’t told us to get angry about that. Have you even heard of the ongoing massacres in West Darfur? Why the hierarchy of atrocities? If the military-industrial complex does not have an interest in these places, you will not hear about them. You will hear about the corrupt oligarchies you are supposed to hate but not about special interests that run Washington DC. In this environment, the way we see the world and our place in it becomes highly distorted.

Instead of harnessing Russia’s vast oil and gas supplies and integrating it into a pan-European powerhouse, we have made it into an enemy and pushed it towards China (our genuine rival). Yes, Russia is a deeply problematic country, scarred by a century of communism. Yet they are people who you can do business with if you respect their interests and treat them equally. Instead of trying to bring Iran and Saudi Arabia together to heal and develop the Middle East (which China successfully started doing), we are now seizing on this opportunity to bang the drum for war with Iran while arming Saudi Arabia to the teeth. Yes, Iran is also a seriously problematic country, but we have meddled in their affairs and waged hybrid war against them for decades. We deposed their first democratic leader replacing him with a decadent monarch who sparked an Islamic revolution. Since then, our aggressive stance in the Middle East encouraged them to develop nuclear weapons. The P5+1 deal was a step in the right direction, and there is no reason we can’t go back to that kind of preventive diplomacy. Their resilience to our sanctions shows they are at least enterprising.We are not as powerful as we were, and the world isn’t as weak as it was – they want to make money and develop. Whereas we don’t even know what we want. So, we can either up our own game and grow together with emerging countries or die trying to maintain unipolar dominance.

The Monroe Doctrine, one of the founding foreign policy doctrines of the United States, holds interference into the affairs of South and Central America as hostile. In other words, it’s their turf. Yet we deny other major powers any legitimate sphere of influence. ‘Do as I say, not as I do’ isn’t cutting the mustard anymore. Just for a moment think of the anger up and down the land over the weekend, as foreign conflicts played out on our streets, at the same time as one of the few remaining events of ancestor worship in Britain. Now imagine how larger this anger would be if China had military bases in the Republic of Ireland, or if Russia was funding a violent Republican overthrow of Stormont. We need a sense of perspective.

At a time of peak ignorance of the rest of the world, our domestic woes in the UK have never been more connected to global goings on. This is the sad paradox we find ourselves in. Our soft power erodes as we dilute our culture and destroy the fabric of traditional, family life. Our hard power is under-resourced and overstretched, leading to no strategic objective, and resulting in a lot of dead or traumatised soldiers and many more people who hate us with a vengeance. Our foreign policy – which is completely dictated by the U.S. – has radicalised parts of the immigrant populations we have brought in and left us exposed to unknown numbers of hostile actors. Sanctions warfare is paid for by the heating and shopping bills of the working class.

Brexit exposed the reality of how deeply controlled the UK is by international organisations. If you thought trying to decouple from the EU was an impossible task, detangling ourselves from NATO and the U.S. intelligence apparatus will be an entirely different ballgame. Brexit also revealed a genuine desire by the British public to be that global, independent, sovereign trading-nation making its own deals with countries across the world, not beholden to outdated policies and the groupthink of corporate-controlled politicians and the technocrats under them. Well, to actually do that we need to embrace a multipolar world and have a bit of confidence in ourselves.

Just as Remainers said we were too small and insignificant to survive outside the EU, so too will people say that we are too small and insignificant to survive outside the NATO/U.S. umbrella. It is doubtful there will be a NATO in a decade from now, so we might not have a choice. It is also likely the U.S. will suffer greatly (along with the whole world) from the eventual collapse of the dollar, finding it hard to avoid some form of civil conflict. Until then the music will still play on the titanic, but will the UK have the sense to get on the nearest lifeboat? As much as a military alliance provides protection from potential enemies, it also forces members to take on enemies that they might not ordinarily have, leaving them more exposed and then in need of protection.

Those imbued with the neoconservative zest for spreading liberal values by the bullet and bombing the world into democracy will no doubt be horrified by the suggestions made here, not being able to conceive of a Britain that doesn’t play the role of shit on the U.S. jackboot. I recall a different Britain, however. One that had the best diplomatic service in the world, staffed by the greatest linguists. A Britain that had state capacity and the ability to execute its will. A country that despite its allegiances was able to identify and pursue its own genuine national interest. To return to this state we ultimately must fix ourselves domestically and as a society. Until then, it would do no harm to pursue a more sophisticated approach to dealing with the rest of the world.By learning the difference between being allies with a country and being stuck in a political-military straitjacket with them, the West has an opportunity to revitalise itself and thrive in a multipolar world.

Deprived of global empire, the U.S. will be able to fight off its leviathan corporate oligarchy and develop to full potential. Europe will be able to pursue its own security and economic interests, not just American ones. Realpolitik will make its triumphant return. The UK, perhaps in the best position of all, will be able to take advantage of not being a subordinate and truly become ‘Global Britain’. I urge readers to reject those who want a war of civilisations and embrace this positive, sensible, and more human way to approach our future and the world.

Post Views: 1,061 -

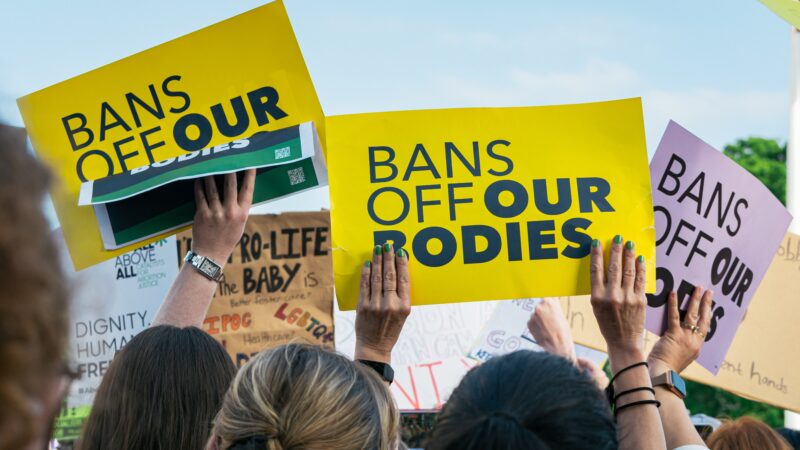

Roe v Wade Reaction

The news that the US Supreme Court has overturned Roe v. Wade has divided opinion. Here is our first debate piece on the issue: we have two different views from two different young women about the issue.

Pro-Choice:

Olivia Lever is the director of Blue Beyond. You can follow her at @liv_lever on Twitter:

‘I feel very annoyed and frustrated. A woman should have the right to choose in the 2022, and the state should never have interference over a woman’s body – it is very similar to the vaccine debate, the state should have no say in what you do with your body. In a practical sense, sex education and social infrastructure in the States is very poor.

On a post note, there is no mention of social infrastructure being made better to help those that have to have babies not be struck down by the financial burden or making sure that these children don’t have less of a life than they should. The whole thing is so poorly thought out, plus the US is supposed to be secular. It’s the constitutional principle. We could lose same-sex marriage and gay marriage. It’s stupid to lose contraception seeing as it prevents abortion.’

Pro-Life:

@BeatriceSEM takes the opposite view:

‘Absolutely delighted and feeling pretty emotional. The number of babies who will now be given a chance at life is massive! I hope very much other countries follow suit!’

Post Views: 901