According to the race report published last year, 63% of Black caribbean households are single parent households, as opposed to the black african community who is at 43%, the UK’s rate is 14.7%. The culture for the black community in the UK is quite similar to the US which also has problems with black on black crime, low literacy rates and father absence. The larger question that has raged between left and right for centuries is nature or nurture? How much control does an ethnic minority have over their fate?

What we are discussing is not an issue exclusive to the black community. “Redneck culture” , a term used by Thomas Sowell to describe a subculture prevalent in ghettos, encourages a way of life and mentality that is not conducive to the success of any community. A quote from his book White Liberals and Black Rednecks used to describe the southern white population follows: “ proneness to violence, neglect of education, sexual promiscuity… reckless searches for excitement, lively music and dance etc” This is only a short sample from a long list of cultural behaviours that without knowing the topic of focus, would be thought exclusive to the black community.

What the leftist intelligentsia often leave out of conversations about race are the effects of culture and values within a community. Not every ill can be attributed to the supposed “effects of capitalism”. The left’s obsession with proving that racism causes inequality has meant that many problems that could be solved independent of the state, are used as incentives to garner the black vote.

With the data available by comparing the different ethnic communities in the UK we should be able to see the effect that values have on a community, which largely shows that the Black African community does much better in education and has lower rates of expulsion for pupils alongside better mental health. This is especially outstanding as the things mentioned above are named as social behavioral problems, arising from single parenthood. As the lack of a paternal and/or maternal influence are proven to negatively affect emotional control for example higher levels of aggression. Could this be why Caribbean pupils are twice as likely to get temporarily excluded at 10.2% compared to 4.2%. They also have the highest rates of detention under the mental health act.

The black community in Britain faces a large issue of knife crime where between 2017 and 2020 black people aged 15-17 made up 47% of homicide victims. Sadiq Khan even predicts a rise in violent crime in London due to the cost of living crisis.

Aside from behavioral problems, Caribbean pupils are also far more likely than African students to do worse in education. Which should be the top priority for growth in any community as it leads to higher paid jobs. Although black pupils as a whole are more likely to go to university than white pupils. Black Caribbean students are the most likely to go into high tariff universities. Could this possibly be because there is a lack of educational importance in the Caribbean community, which means that African pupils progress further? 10.9% of black caribbean compared to 17.3% of African pupils gain 3 A’s at A Level.

Now immigrants do tend to do better in education, but not all immigrants do equally well. 42% of the Chinese population gained 3 A’s and 33.2% of Indians followed by 26% of white students. Which indicates that their fate is not fixed but contrary, and that immigrant children often outperform white students.

What the black community has is not primarily an issue of race but of culture, which requires steady homes and values to fix, that which conservatism provides.

You Might also like

-

Atatürk: A Legacy Under Threat

The founders of countries occupy a unique position within modern society. They are often viewed either as heroic and mythical figures or deeply problematic by today’s standards – take the obvious examples of George Washington. Long-held up by all Americans as a man unrivalled in his courage and military strategy, he is now a figure of vilification by leftists, who are eager to point out his ownership of slaves.

Whilst many such figures face similar shaming nowadays, none are suffering complete erasure from their own society. That is the fate currently facing Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, whose era-defining liberal reforms and state secularism now pose a threat to Turkey’s authoritarian president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

To understand the magnitude of Atatürk’s legacy, we must understand his ascent from soldier to president. For that, we must go back to the end of World War One, and Turkey’s founding.

The Ottoman Empire officially ended hostilities with the Allied Powers via the Armistice of Mudros (1918), which amongst other things, completely demobilised the Ottoman army. Following this, British, French, Italian and Greek forces arrived in and occupied Constantinople, the Empire’s capital. Thus began the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire: having existed since 1299, the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) ceded large amounts of territory to the occupying nations, primarily being between France and Great Britain.

Enter Mustafa Kemal, known years later as Atatürk. An Ottoman Major General and fervent anti-monarchist, he and his revolutionary organisation (the Committee of Union and Progress) were greatly angered by Sèvres, which partitioned portions of Anatolia, a peninsula that makes up the majority of modern-day Turkey. In response, they formed a revolutionary government in Ankara, led by Kemal.

Thus, the Turkish National Movement fought a 4-year long war against the invaders, eventually pushing back the Greeks in the West, Armenians in the East and French in the South. Following a threat by Kemal to invade Constantinople, the Allies agreed to peace, with the Treaty of Kars (1921) establishing borders, and Lausanne (1923) officially settling the conflict. Finally free from fighting, Turkey declared itself a republic on 29 October 1923, with Mustafa Kemal as president.

His rule of Turkey began with a radically different set of ideological principles to the Ottoman Empire – life under a Sultan had been overtly religious, socially conservative and multi-ethnic. By contrast, Kemalism was best represented by the Six Arrows: Republicanism, Populism, Nationalism, Laicism, Statism and Reformism. Let’s consider the four most significant.

We’ll begin with Laicism. Believing Islam’s presence in society to have been impeding national progress, Atatürk set about fundamentally changing the role religion played both politically and societally. The Caliph, who was believed to be the spiritual successor to the Prophet Muhammad, was deposed. In their place came the office of the Directorate of Religious Affairs, or Diyanet – through its control of all Turkey’s mosques and religious education, it ensured Islam’s subservience to the State.

Under a new penal code, all religious schools and courts were closed, and the wearing of headscarves was banned for public workers. However, the real nail in the coffin came in 1928: that was when an amendment to the Constitution removed the provision declaring that the “Religion of the State is Islam”.

Moving onto Nationalism. With its roots in the social contract theories of thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Kemalist nationalism defined the social contract as its “highest ideal” following the Empire’s collapse – a key example of the failures of a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural state.

The 1930s saw the Kemalist definition of nationality integrated into the Constitution, legally defining every citizen as a Turk, regardless of religion or ethnicity. Despite this however, Atatürk fiercely pursed a policy of forced cultural conformity (Turkification), similar to that of the Russian Tsars in the previous century. Both regimes had the same aim – the creation and survival of a homogenous and unified country. As such, non-Turks were pressured into speaking Turkish publicly, and those with minority surnames had to change, to ‘Turkify’ them.

Now Reformism. A staunch believer in both education and equal opportunity, Atatürk made primary education free and compulsory, for both boys and girls. Alongside this came the opening of thousands of new schools across the country. Their results are undeniable: between 1923 – 38, the number of students attending primary school increased by 224%, and 12.5 times for middle school.

Staying true to his identity as an equal opportunist, Atatürk enacted monumentally progressive reforms in the area of women’s rights. For example, 1926 saw a new civil code, and with it came equal rights for women concerning inheritance and divorce. In many of these gender reforms, Turkey was well-ahead of other Western nations: Turkish women gained the vote in 1930, followed by universal suffrage in 1934. By comparison, France passed universal suffrage in 1945, Canada in 1960 and Australia in 1967. Fundamentally, Atatürk didn’t see Turkey truly modernising whilst Ottoman gender segregation persisted

Lastly, let’s look at Statism. As both president and the leader of the People’s Republican Party, Atatürk was essentially unquestioned in his control of the State. However, despite his dictatorial tendencies (primarily purging political enemies), he was firmly opposed to dynastic rule, like had been the case with the Ottomans.

But under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, all of this could soon be gone.

Having been a high-profile political figure for 20 years, Erdoğan has cultivated a positive image domestically, one focused on his support for public religion and Turkish nationalism, whilst internationally, he’s received far more negative attention focused on his growing authoritarian behaviour. Regarded widely by historians as the very antithesis of Atatürk, Erdoğan’s pushback against state secularism is perhaps the most significant attack on the founder’s legacy.

This has been most clearly displayed within the education system. 2017 saw a radical shift in school curriculums across Turkey, with references to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution being greatly reduced. Meanwhile, the number of religious schools has increased exponentially, promoting Erdoğan’s professed goal of raising a “pious generation of Turks”. Additionally, the Diyanet under Erdoğan has seen a huge increase in its budget, and with the launch of Diyanet TV in 2012, has spread Quranic education to early ages and boarding schools.

The State has roles to play in society but depriving schoolchildren of vital scientific information and funding religious indoctrination is beyond outrageous: Soner Cagaptay, author of The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey, referred to the changes as: “a revolution to alter public education to assure that a conservative, religious view of the world prevails”.

There are other warning signs more broadly, however. The past 20 years have seen the headscarf make a gradual reappearance back into Turkish life, with Erdoğan having first campaigned on the issue back in 2007, during his first run for the presidency. Furthermore, Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), with its strong base of support amongst extremely orthodox Muslims, has faced repeated accusations of being an Islamist party – as per the constitution, no party can “claim that it represents a form of religious belief”.

Turkish women, despite being granted legal equality by Atatürk, remain the regular victims of sexual harassment, employment discrimination and honour killings. Seemingly intent on destroying all the positive achievements of the founder, Erdoğan withdrew from the Istanbul Convention (which forces parties to investigate, punish and crackdown on violence against women) in March 2021.

All of these reversals of Atatürk’s policies reflect the larger-scale attempt to delete him from Turkey’s history. His image is now a rarity in school textbooks, at national events, and on statues; his role in Turkey’s founding has been criminally downplayed.

President Erdoğan presents an unambiguous threat to the freedoms of the Turkish people, through both his ultra-Islamic policies and authoritarian manner of governance. Unlike Atatürk, Erdoğan seemingly has no problems with ruling as an immortal dictator, and would undoubtedly love to establish a family dynasty. With no one willing to challenge him, he appears to be dismantling Atatürk’s reforms one law at a time, reducing the once-mythical Six Arrows of Kemalism down to a footnote in textbooks.

A man often absent from the school curriculums of Western history departments, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk proved one of the most consequential leaders in both Turkish history, and the 20th Century. A radical and a revolutionary he may have been, but it was largely down to him that the Turkish people received a recognised nation-state, in which state secularism, high-quality education and equal civil rights were the norm.

In our modern world, so many of our national figures now face open vilification from the public and politicians alike. But for Turkey, future generations may grow up not even knowing the name or face of their George Washington. Whilst several political parties and civil society groups are pushing back against this anti-Atatürk agenda, the sheer determination displayed by Erdoğan shows how far Turks must yet go to preserve the founder’s legacy.

Post Views: 856 -

Technology Is Synonymous With Civilisation

I am declaring a fatwa on anti-tech and anti-civilisational attitudes. In truth, there is no real distinction between the two positions: technology is synonymous with civilisation.

What made the Romans an empire and the Gauls a disorganised mass of tribals, united only by their reactionary fear of the march of civilisation at their doorstep, was technology. Where the Romans had minted currency, aqueducts, and concrete so effective we marvel on how to recreate it, the Gauls fought amongst one another about land they never developed beyond basic tribal living. They stayed small, separated, and never innovated, even with a whole world of innovation at their doorstep to copy.

There is always a temptation to look towards smaller-scale living, see its virtues, and argue that we can recreate the smaller-scale living within the larger scale societies we inhabit. This is as naïve as believing that one could retain all the heartfelt personalisation of a hand-written letter, and have it delivered as fast as a text message. The scale is the advantage. The speed is the advantage. The efficiency of new modes of organisation is the advantage.

Smaller scale living in the era of technology necessarily must go the way of the hand-written letter in the era of text messaging: something reserved for special occasions, and made all the more meaningful for it.

However, no-one would take seriously someone who tries to argue that written correspondence is a valid alternative to digital communication. Equally, there is no reason to take seriously someone who considers smaller-scale settlements a viable alternative to big cities.

Inevitably, there will be those who mistake this as going along with the modern trend of GDP maximalism, but the situation in modern Britain could not be closer to the opposite. There is only one place generating wealth currently: the South-East. Everywhere else in the country is a net negative to Britain’s economic prosperity. Devolution, levelling up, and ‘empowering local communities’ has been akin to Rome handing power over to the tribals to decide how to run the Republic: it has empowered tribal thinking over civilisational thinking.

The consequence of this has not been to return to smaller-scale ways of life, but instead to rest on the laurels of Britain’s last civilisational thinkers: the Victorians.

Go and visit Hammersmith, and see the bridge built by Joseph Bazalgette. It has been boarded up for four years, and the local council spends its time bickering with the central government over whose responsibility it is to fix the bridge for cars to cross it. This is, of course, not a pressing issue in London’s affairs, as the Vercingetorix of the tribals, Sadiq Khan, is hard at work making sure cars can’t go anywhere in London, let alone across a bridge.

Bazalgette, in contrast to Khan, is one of the few people keeping London running today. Alongside Hammersmith Bridge, Bazalgette designed the sewage system of London. Much of the brickward is marked with his initials, and he produced thousands of papers going over each junction, and pipe.

Bazalgette reportedly doubled the pipes diameters remarking “we are only going to do this once, and there is always the possibility of the unforeseen”. This decision prevented the sewers from overflowing in 1960.

Bazalgette’s genius saved countless lives from cholera, disease, and the general third-world condition of living among open excrement. There is no hope today of a Bazalgette. His plans to change the very structure of the Thames would be Illegal and Unworkable to those with power, and the headlines proposing such a feat (that ancient civilisations achieved) would be met with one million image macros declaring it a “manmade horror beyond their comprehension.”

This fundamentally is the issue: growth, positive development, and a future worth living in is simply outside the scope of their narrow comprehension.

This train of thought, having gone unopposed for too long, has even found its way into the minds of people who typically have thorough, coherent, and well-thought-out views. In speaking to one friend, they referred to the current ruling classes of this country as “tech-obsessed”.

Where is the tech-obsession in this country? Is it found in the current government buying 3000 GPUs for AI, which is less than some hedge funds have to calculate their potential stocks? Or is it found in the opposition, who believe we don’t need people learning to code because “AI will do it”?

The whole political establishment is anti-tech, whether crushing independent forums and communities via the Online Harms Bill, to our supposed commitment to be a ‘world leader in AI regulation’ – effectively declaring ourselves to be the worlds schoolmarm, nagging away as the US, China, and the rest of the world get to play with the good toys.

Cummings relays multiple horror stories about the tech in No. 10. Listening to COVID figures down the phone, getting more figures on scraps of paper, using the calculator on his iPhone and writing them on a Whiteboard. Fretting over provincial procurement rules over a paltry 500k to get real-time data on a developing pandemic. He may well have been the only person in recent years serious about technology.

The Brexit campaign was won by bringing in scientists, physicists, and mathematicians, and leveraging their numeracy (listen to this to get an idea of what went on) with the latest technology to campaign to people in a way that had not been done before. Technology, science, and innovation gave us Brexit because it allowed people to be organised on a scale and in ways they never were before. It was only through a novel use of statistics, mathematical models, and Facebook advertising that the campaign reached so many people. The establishment lost on Brexit because they did not embrace new modes of thinking and new technologies. They settled for basic polling of 1-10 thousand people and rudimentary mathematics.

Meanwhile the Brexit campaign reached thousands upon thousands, and applied complex Bayesian statistics to get accurate insights into the electorate. It is those who innovate, evolve, and grow that shape the future. There is no going back to small-scale living. Scale is the advantage. Speed is the advantage. And once it exists, it devours the smaller modes of organisation around it, even smaller modes of organisation have the whole political establishment behind it.

When Cummings got what he wanted injected into the political establishment – a data science team in No. 10 – they were excised like a virus from the body the moment a new PM was installed. Tech has no friends in the political establishment, the speed, scale, and efficiency of the thing is anathema to a system which relies on slow-moving processes to keep a narrow group of incompetents in power for as long as possible. The fierce competition inherent to technology is the complete opposite of the ‘Rolls-Royce civil service’ which simply recycles bad staff around so they don’t bother too many people for too long.

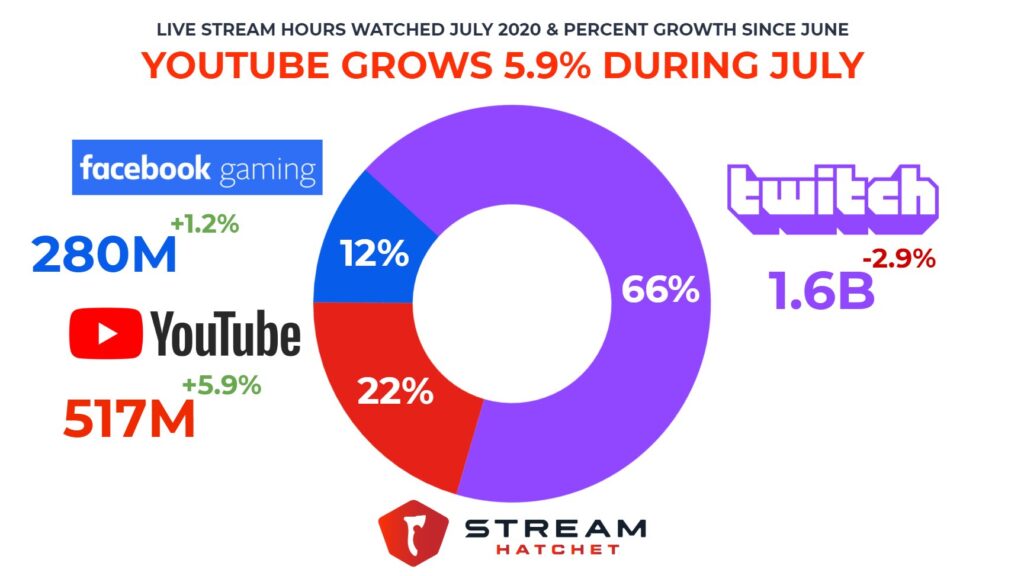

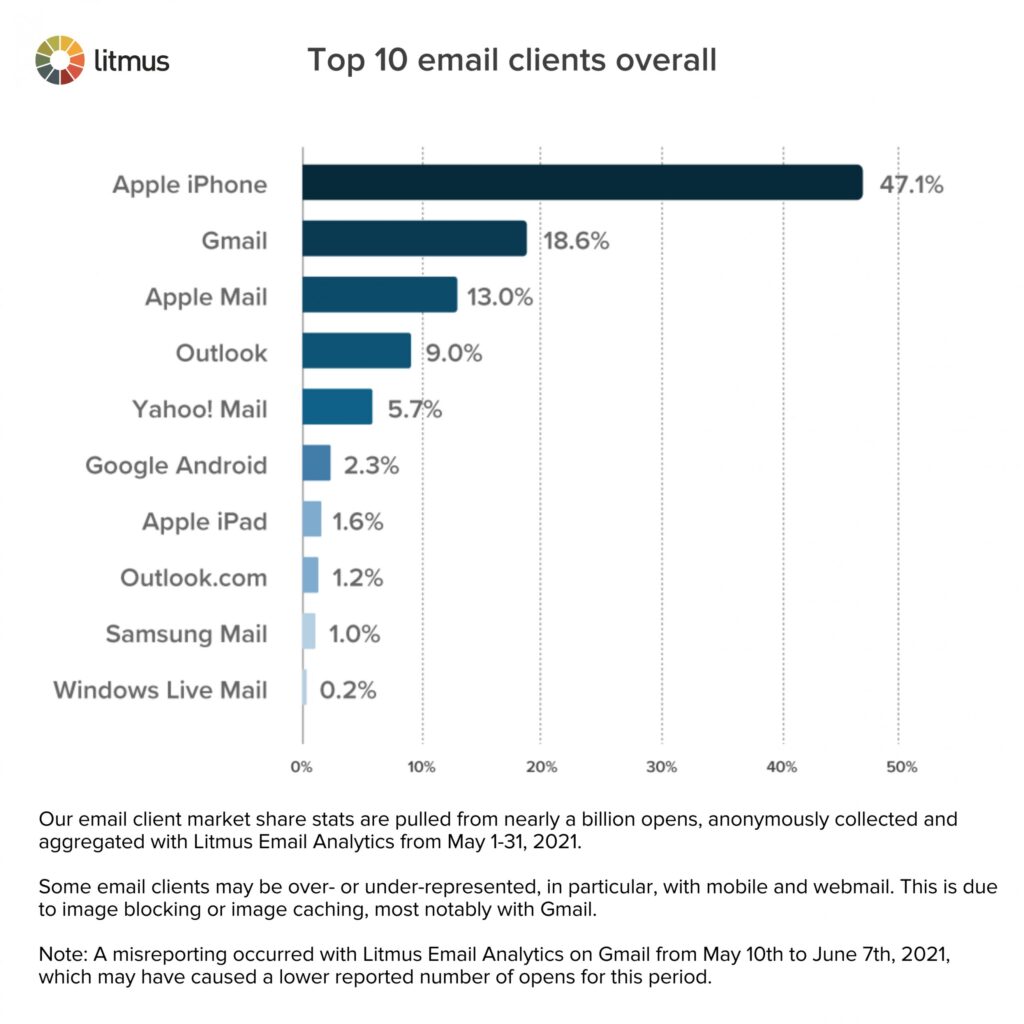

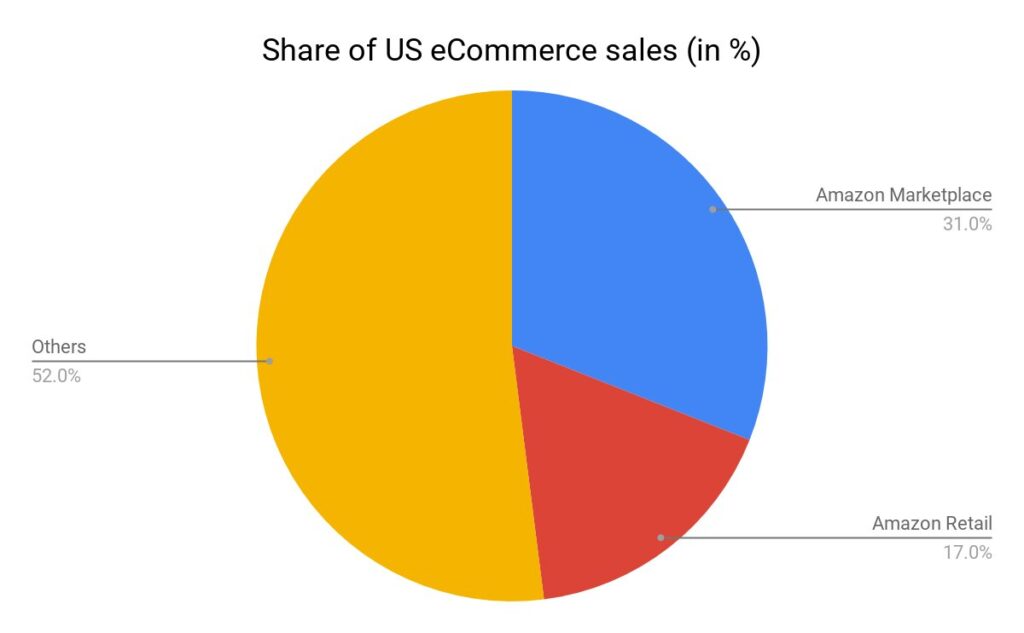

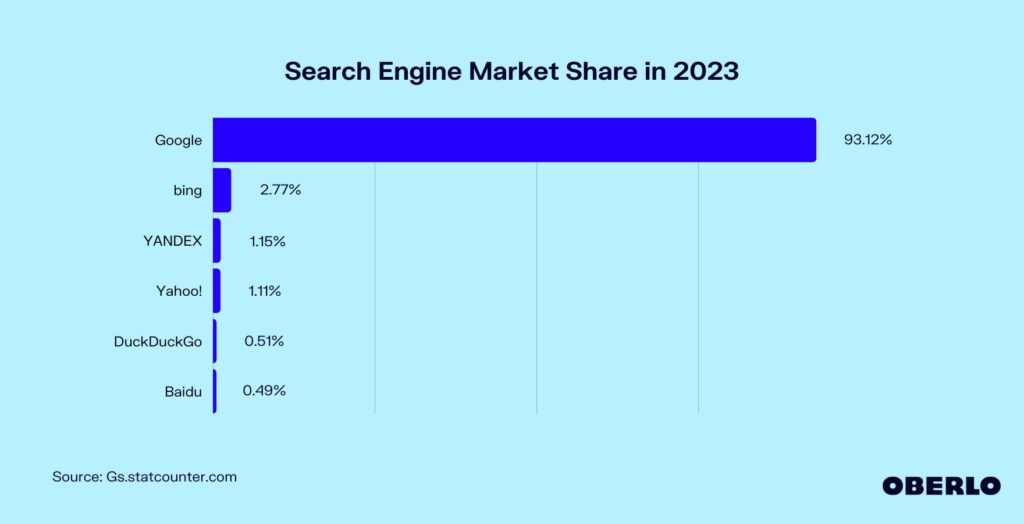

By contrast, in tech, second best is close to last. When you run the most popular service, you get the data from running that service. This allows you to make a better service, outcompete others, which gets you more users, which gets you more data, and it all snowballs from there. Google holds 93.12% of the search engine market share. Amazon owns 48% of eCommerce sales. The iPhone is the most popular email client, at 47.13%. Twitch makes up 66% of all hours of video content watched. Google Chrome makes up 70% of web traffic. There next nearest competitor, Firefox (a measly 8.42%,) is only alive because Google gave them 0.5b to stick around. Each one of these companies is 2-40 times bigger than its next nearest competitor. Just as with civilisation, there is no half-arseing technology. It is build or die.

Nevertheless, there have been many attempts to half-ass technology and civilisation. When cities began to develop, and it became clear they were going to be the future powerhouses of modern economies, theorists attempted to create a ‘city of towns’ model.

Attempting to retain the virtues of small town and community living in a mass-scale settlement, they argued for a model of cities that could be made up of a collection of small towns. Inevitably, this failed.

The simple reason is that the utility of cities is scale. It is the access to the large labour pools that attracts businesses. If cities were to become collections of towns, there would be no functional difference in setting up a business in a city or a town, except perhaps the increased ground rent. The scale is the advantage.

This has been borne out mathematically. When things reach a certain scale, when they become networks of networks (the very thing you’re using, the internet, is one such example) they tend towards a winner-takes-all distribution.

Bowing out of the technological race to engage in some Luddite conquest of modernity, or to exact some grudge against the Enlightenment, is signalling to the world we have no interest in carving out our stake in the future. Any nation serious about competing in the modern world needs to understand the unique problems and advantages of scale, and address them.

Nowhere is this more strongly seen than in Amazon, arguably a company that deals with scale like no other. The sheer scale of co-ordination at a company like Amazon requires novel solutions which make Amazon competitive in a way other companies are not.

For example, Amazon currently owns the market on cloud services (one of the few places where a competitor is near the top, Amazon: 32%, Azure: 23%). Amazon provides data storage services in the cloud with its S3 service. Typically, data storage services have to handle peak times, when the majority of the users are online, or when a particularly onerous service dumps its data. However, Amazon services so many people – its peak demand is broadly flat. This allows Amazon to design its service around balancing a reasonably consistent load, and not handling peaks/troughs. The scale is the advantage.

Amazon warehouses do not have designated storage space, nor do they even have designated boxes for items. Everything is delivered and everything is distributed into boxes broadly at random, and tagged by machines so the machines know where to find it.

One would think this is a terrible way to organise a warehouse. You only know where things are when you go to look for them, how could this possibly be advantageous? The advantage is in the scale, size, and randomness of the whole affair. If things are stored on designated shelves, when those shelves are empty the space is wasted. If someone wants something from one designated shelf on one side of the warehouse, and something from another side of the factory, you waste time going from one side to the other. With randomness, you are more likely to have a desired item close by, as long as you know where that is, and with technology you do. Again, the scale is the advantage.

The chaos and incoherence of modern life, is not a bug but a feature. Just as the death of feudalism called humans to think beyond their glebe, Lord, and locality, the death of legacy media and old forms of communication call humans to think beyond the 9-5, elected representative, and favourite Marvel movie.

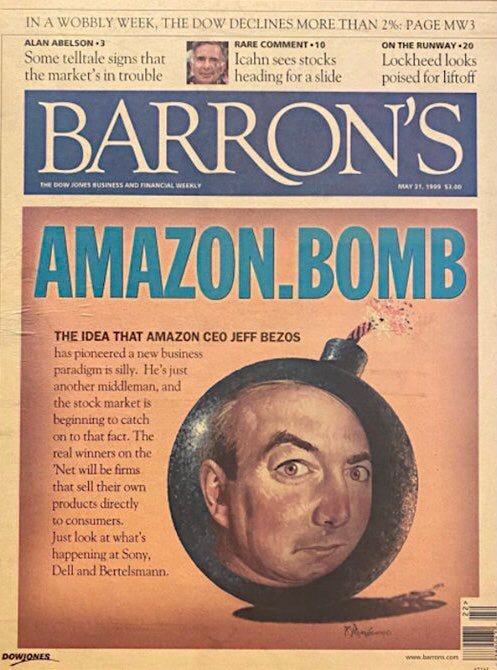

In 1999, one year after Amazon began selling music and videos, and two years after going public – Barron’s, a reputable financial magazine created by Dow Jones & Company posted the following cover:

Remember, Barron’s is published by Dow Jones, the same people who run stock indices. If anyone is open to new markets, it’s them. Even they were outmanoeuvred by new technologies because they failed to understand what technophobes always do: scale is the advantage. People will not want to buy from 5 different retailers because they want to buy everything all at once.

Whereas Barron’s could be forgiven for not understanding a new, emerging market such as eCommerce, there should be no sympathy for those who spend most of their lives online decrying growth. Especially as they occupy a place on the largest public square to ever occur in human existence.

Despite claiming they want a small-scale existence, their revealed preference is the same as ours: scale, growth, and the convenience it provides. When faced with a choice between civilisation in the form of technology, and leaving Twitter a lifestyle closer to that of the past, even technology’s biggest enemies choose civilisation.

Post Views: 1,058 -

Labour’s Plans for Constitutional Reform

First principles

We need to begin by understanding what a constitution is and what it ought to do. The history of the constitution as a political idea is one in which a single term came to be associated with the twin principles of the “spirit” of the people over whom politics is exercised, and the “health” of the body politic from whom the government is drawn.

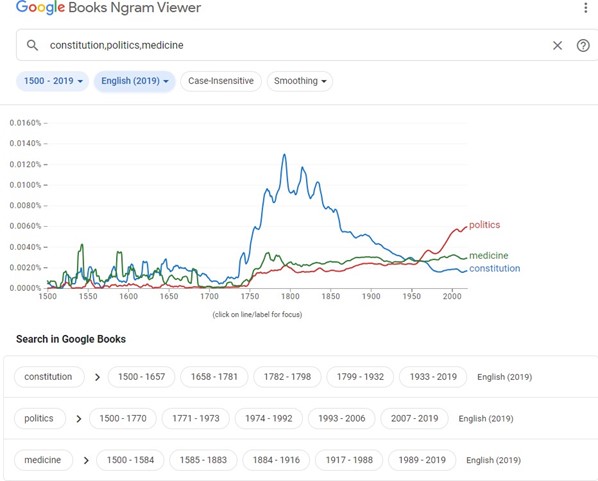

It is no coincidence that the word “constitution” emerged in politics to refer to the central laws (written or otherwise) that govern a community, during a period of increased use in the medical community to mean “health”.

A simple Ngram chart shows that, whilst “medicine” and “constitution” have an established history of coterminous use, from the mid-1720s onwards – a time of increasing popularity of focusing on constitutions in the modern sense as a written set of basic rules upon which all laws should be based – the use of constitution skyrockets.

Carl Schmitt wrote in the 1920s that a constitution ought to be a reflection of the people, as they exist simultaneously above and below the political order that seeks to represent them in the world. Above, because like Hobbes’ Leviathan they tower over all political figures in judgement; below, because they are the very foundation upon which all political institutions can be built. If a people ceases to exist, then the institutions become hollow machines turning and maintaining themselves for nobody but themselves. And it must be remembered that institutions, as all things incorporated in some way, become entities in themselves.

A constitution is, therefore, simultaneously the spirit and mind of the people. The spirit, because it captures what Montesquieu attempted to identify in L’Esprit de Loi, the spirit of the laws; the truth that there is something intangible behind the tangible laws by which political institutions operate. In other words, rather than analysing the laws that existed, Montesquieu asked why those laws existed, rather than some other set of laws, in the political community in which they were practised. Why did the English have the common law, when the French had parlements? Etc.

The mind, because the constitution moves beyond unthinking instinct and into the strategic realm of forward thinking, extended temporal existence and predictable security. As Montesquieu feared of tyranny, and as Hegel recognised of Spirit in Man’s infancy, when the law becomes the domain of a single person, fear is the spirit of the legal order because there is no predictability, no consistency. Arbitrariness becomes the basis of decision making. It was not fear as fear of the government itself, but fear of the inability to know what the consequences from the government might be.

A constitution, then, speaks the unspoken sentiments of a people and does so in a consistent and unifying way.

The question that arose in the enlightenment over whether this speaking constitution should move to the page and transform from an unwritten to a written document was, of course, central to what Yuval Levin called the great debate between Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine. Whilst Paine railed against what he saw as the “tyranny of the dead” when Burke defended tradition and custom, Burke gently replied that it is the very dialogue that thrives between the living and the dead that produces freedom; just as a traveller in a forest might wander from the beaten path and find a lush grove, so too might he get lost in a swamp. Innovation and the freedom that experience brings with it is possible only when there is a point from which you begin.

Instead, said Burke, it was that very tyranny – of a dead set of people from a particular moment in time – that would be cemented in a written constitution. Rather than allowing for the continual expression and interrogation of custom and tradition that comes with an unwritten constitution, a codified one would narrow the temporal horizon of a people into a strict moment in time in an attempt to speak forever. Some of the American Framers argued that a way around this would be to revise the constitution at the end of every generation – roughly 19 years or so. Sir Roger Scruton put the problem very (and typically) eloquently when he said that the Treaty of Rome was written in a year that’s gone for a circumstance that has passed by a group of people that are dead.

The two great constitutions that emerged in the late-1700s – in America and in France – had two very different goals that determined the direction in which they moved. America, said the political historian Hannah Arendt, framed a constitution on a set of institutions that already existed expressing a people that already had a heritage. For that reason, the American constitution can be said to have achieved those two goals around which this briefing note has thus far revolved: the expression of the spirit and mind of a people. France, on the other hand, attempted to create a people through the act of constitution: the Bretons, the Provencals, the Roussillions, the Orleanais, all were to be washed away and the remnants dissolved in the universal humanity of la France. The French constitution preceded a people; the American constitution expressed one.

Yet the constitution that has thrived where even the American one has failed has – or had – been the British one.

In their obsession with formalism and written rules, most psephologists have made the mistake of thinking that Britain’s constitution, uncodified though it is, can be found in the many documents that stretch from Magna Carta through the Bill of Rights to the Act of Union to the Great Reform Acts to the Parliament Acts to the Human Rights Act. No – to do so is to mistake a man’s words for the man himself. These are not Britain’s constitution, but the consequences (and in many places, the mutilation) of the constitution itself.

What is Britain’s constitution?

It is the Parliament itself.

Parliament, in the synecdochal slip of the tongue common in modern politics, is not the House of Commons, nor the House of Lords. Not even is it the building in which those assemblies meet. Parliament, as understood by Bagehot, Dicey, Maitland and all the eulogists of Britain, exists when the three traditional branches of British government are assembled in one place: the Monarch; the Lords; and the Commons. Hence, the momentous occasion when the Monarch delivers his speech to the Lords and Commons, Parliament is said to be together.

But why is Parliament Britain’s constitution? Because, properly understood, Parliament is the voice of people in all of its aspects. The Monarch is the people embodied, a singular head of state who gives to the constitution the only missing ingredient from spirit and mind – a body. He is the body of the politic. The Lords are the people as understood by Burke, as a transtemporal entity who speaks for the country as a physical entity – hence why it was tied to land – and a spiritual entity – hence the Lords Spiritual – and a legal entity – hence the Law Lords. The Commons, finally, are the people as understood by Paine, as the vocal element of the constitution, demanding changes in the moment and transient in its demands.

The British Parliament is, and always has been, the constitution. The doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty reflected this fact, that no power exists above Parliament – as the Monarch, Lords and Commons in one.

Labour’s constitutional reforms: past and present

This was undone entirely by New Labour. The greatest acts of constitutional vandalism – the creation of the Supreme Court, the Human Rights Act, the project of devolution, the reforms to the House of Lords – all committed by the forebears of the current administration upended this balance in a way none but constitutional historians loyal to the idea of Britain could have predicted.

Each of these deserves an invective all their own, but the simple fact is that each of these altered the operation of Britain’s constitution in different ways, but creating a legalistic straightjacket around Parliament: the Supreme Court subverted the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty; the Human Rights Act made that Supreme Court loyal to a power beyond the boundaries and popular

control of Britain; devolution created parallel laws applying to the same citizens at different times and in different places across the country; and the neutering of the hereditary aristocracy resulted in an upper chamber dedicated to ambition, avarice and cronyism.

Thus the supreme entity of this nation – Parliament – has ceased to act as a unitary government and now must act as one amongst many. And by extension – and by design – the constitution has died.

This is the scene into which the new administration enters, ready to finish the job through solutions to a problem of its own making. One of the greatest architects of this situation, Gordon Brown, penned a document aimed at creating a “Reformed United Kingdom” by empowering the different regions of the United Kingdom to be competitors to the central government in Westminster, whilst the absurd phrase of “devolution deserts” now seeks to spread the insanity of an unequal legal landscape across the whole map of the British Isles.

These plans will make a legal reality the idea that Westminster is the English parliament and merely one amongst many. When Brown began his document by stating that “the crisis we face in Britain is not just short-term – it is deep-seated”, he did so without a hint of irony.

Why?

The reader might be left thinking, why? Why did New Labour do all of this, and why does Labour now seek to carry us further down this road?

By design or not, the New Labour government destroyed the constitution of this country because it blew apart the unity needed to underpin the idea of a people. Alongside the administrative vandalism of devolution – which exacerbated the delusions that the Scots and the Welsh, whilst culturally different to the English, are not legally the same nor subjects of the same crown – the surrendering of the nations courts’ abilities to mediate between its citizens to a foreign power only made worse the emerging sense of dual loyalty that was gestating in an increasingly multicultural Britain. The amazement that integration has ceased in Britain whilst the legal tradition of this country has been hollowed out has never yet joined the dots to arrive at the simple conclusion that integration is impossible in the current administrative state masquerading as a constitution.

Yet this is not the only reason Labour now pursues these goals. Indeed, it does so because it must. We have moved from circumstances in which a constitution might have been written to express a people that already existed – indeed, the people, understood properly as a transtemporal entity, never old or dying nor young or being born, that has occupied these islands for centuries – to circumstances in which a constitution must be written to summon a people into being.

We are France at the height of the revolution. The idea of Britain is being re-written, and re-constituted, because Britain has died. The elegists – Scruton in his England, an Elegy; Hitchens, in his The Abolition of Britain; and Murray, in his Strange Death of Europe – mourned a people that has passed away. Labour must now begin the process of constructing a new one, based on “values” and “identity”. And it must do so because it began this process 25 years ago.

Post Views: 581