In a world that is innately tragic, how does one remain cheerfully vital? There seems no end to the forces that wish to crush one’s joie de vivre. Whether it’s the deadening omnipotence of the modern technocratic mode of organisation, the overbearing coddling of our moralistic culture, or just the old-fashioned primordial fate of the great tragedians and philosophers, we cannot escape an assault of forces intent of making us submit to despair.

The world often feels like a great slimy toad, sitting on our chests and allowing its toxic ooze to envelope our nostrils and lungs until we choke. How many people give in to it I wonder? Millions? How many human beings surrender their souls to the devilish incubus that haunts them? This is the primary question of human existence and one that has become pertinent to the present moment in art. In a high culture full of worthless slush that threatens to drown us all in its mediocrity and potent purposelessness, the moment of choice is thrust upon us all as individuals: either we swim to sweet terra firma or fall beneath the murky surface.

Yet, as old King Canute once showed us, the tide is never-ending. In a deeper, spiritual sense the assault of despair will never end. We die and suffer. Our loved ones die and suffer. Religions are exhausted and nations fall to ruins. Given this, do we still have the strength to embrace life?

This is an excerpt from “Blast!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

You Might also like

-

“Traditionalism: The Radical Project for Restoring Sacred Order”, by Mark Sedgwick (Book Review)

In 2014, speaking via Skype to a conference held at the Vatican, Donald Trump’s later advisor, Steve Bannon, casually mentioned Julius Evola (1898-1974), a thinker little known outside Italy, and who even within Italy was conventionally dismissed as a former Fascist whose writings still exerted a pernicious influence on the ’far right’. When that comment was unearthed by the US media in 2016, it sparked a furore amongst those desperate to discredit Trump as a danger to democracy. It also drew mainstream attention to a strange and possibly wide-reaching philosophy.

Evola’s Fascist sympathies went much deeper than anti-communist or nationalist sentiment, being rooted at least partly in a colourful and irrational worldview referred to by some authors (although not Evola) as ‘Traditionalism’. Through him, Bannon, and so by extension Trump, were potentially ‘linked’ to much broader intellectual currents, with connections across everything from the abstractest metaphysics to the earthiest ecologism.

There existed, obscure but important scholars had long argued, a mystical ‘perennial philosophy’ of transcendent religiosity and social stratification that was simultaneously as ancient as origin myths and applicable to modern discontents. Over the centuries, this concept has attracted intellectuals as diverse as the 15th century humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, and Brave New World author Aldous Huxley. Other than Evola, its best-known and most systematic modern exponents were two metaphysicians, the Frenchman René Guénon (1886-1951), and the Swiss Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998), who issued writings and launched initiatives that channeled underlying cultural gloom, and still resonate powerfully. Like Evola, Guénon did not use the term Traditionalism, but his writings are regarded as key texts.

As well as Bannon, ‘Traditionalist’ sympathies of some kind were avowed by, or detectable in, influencers outside America – Hungarian politician Gábor Vona, the Russian ideologue Aleksandr Dugin (whom Bannon met in 2018, and who was supposedly an influence on Putin), and the Brazilian writer, Olavo de Carvalho, credited with helping Jair Bolsonaro win the presidency in 2019. Beyond politics, the connections were even more diffuse, with well-known academics, artists and even King Charles III (when Prince of Wales), articulating Traditionalist tropes to combat anomie and materialism, and promote organic agriculture, small-scale economics, traditional arts, and interfaith dialogue. But did all these different things have anything in common other than root-and-branch discontent with a drably dispiriting status quo? What possible relevance could Traditionalists’ distaste for democracy, and even politics, have for determinedly populist politicians?

This is a long-standing area of interest for Oxford-educated Arabist, Mark Sedgwick, now professor of Arab and Islamic Studies at Aarhus University. His 2003 book, Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century, was the first to draw mainstream attention to Evola, Guénon, Schuon, and others dubbed or self-described as Traditionalists. He brings to this discussion special insight into Islamic influences on Traditionalism, from the inner ecstasies of Sufism to the academically distinguished elucubrations of the contemporary Iranian-American theologian, Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Along the way, he treats ably and interestingly of many subjects, from Hindu ideas about caste via 17th century theories of history to the trajectory of Western feminism, and analyses the influence of Jordan Peterson, whom he regards as a Traditionalist for the internet age.

Traditionalism is a catch-all sort of term, and its outcomes are so diverse it is difficult to discern much consistency at all. Had it not been for Bannon’s remark, it is hard to imagine many even noticing Traditionalism existed. Conceptual complexity could help account for Traditionalism’s apparent ascent; as the author notes, “That which is not easy to understand is not easy to deny”. Sedgwick also suggests that Guénon’s theories may be fundamentally flawed because based on early 20th century understandings of ‘the East’ which are now regarded as too colourful and generic, even condescendingly ‘Orientalist’. Evola’s more dynamic and Western-oriented variant is likewise a product of its time, suffused with Nietzschean contempt for Christianity, and the epochal pessimism of thinkers like Oswald Spengler (even though he criticized both). Sedgwick nevertheless treats it as a coherent corpus of thought, with much relevance for today.

The central element of all variants of Traditionalism is ‘perennialism’ – the notion that beneath all the exoteric differences of world religions there is a unifying ‘sacred order’ understood only by the deepest thinkers, although hazily intuitable by the masses, if only they can be detached from the trammels of modernity. This is not just a tradition, but the Tradition that unlocks all cosmologies, and renders the most impassioned theological and political disputes not just superficial, but almost risible. Traditionalist writings are predictably esoteric, aimed solely at a supposedly more spiritually attuned elite.

Traditionalists tend to be greatly interested in such things as hermetic philosophy, occultism, shamanism, and symbolism, and believe strongly in what the ethnomusicologist Benjamin R. Teitelbaum called “spiritual mobility” (see his 2020 book, War for Eternity). They regard 21st century preoccupations like equality, gender politics, individualism, material progress, and technology as mere aspects of modernity, harmful or simply inconsequential.

The second ingredient is a belief in cosmic circularity, as opposed to the ideas of inevitable linearity inherent in mainstream Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and so throughout modern politics. The world, in this reading, goes through ‘ages’ of decline that can be followed by renewal. An original golden age of unity and quality is ineluctably succeeded by silver, bronze and ultimately dark ages of increasingly mechanistic reductionism – what Guénon memorably called the “age of quantity” – after which the cosmic wheel turns back to the start.

‘Golden Age’ thinking is common to many civilizations, but there are especially close parallels with the four ages (Yugas) of Hinduism, with ‘Kali Yuga’ (the last, sin-filled age of conflict) a shorthand term for today among ‘Aryan’-interested Rightists. This process is almost irrespective of politics, although some theorists see an expeditious role for ‘disruptors’. Evola saw Fascism as a means of reconstituting the Roman Empire, and Bannon saw (and perhaps still sees) Trump as a kind of creative destroyer of consensus, but politics has been a lower priority for other Traditionalists, who concentrated instead on transformation through self-realization.

It may easily be imagined that Traditionalists are prone to eccentricity; for instance, Evola believed that ‘Aryans’ were descended from an ethereal Arctic race which had decayed as they came south. In the 1980s, a writer calling herself “Alice Lucy Trent” officiated in County Donegal over a small community called the Silver Sisterhood, which worshipped a female deity, sported Victorian clothing, and refused to use electricity. Trent later changed her name to “Miss Martindale”, and moved to Oxford, to found a movement called Aristasia in a modest terraced house, where ambiguous persons wearing dresses and veils would hold ultra-reactionary court in a candle-lit, gramophone-sounding interior, and be seen driving around town majestically in a 1950s car. It was part-pantomime, part-serious critique, at once amusing and interesting.

Sedgwick rues some Rightists’ co-option of some parts of Traditionalism. Indeed, perennialism can be hard to square with ideas about a “clash of civilizations”, or immigration, or belief in physical racial differences (which even Evola downplayed). He nevertheless examines their thinking with commendable fairness. He differentiates between genuinely traditional teachings about religion and society, which really can be millennia old, and 1920s-to-present-day attempts to turn some of these teachings into realities. For Sedgwick, whatever about the youthful Evola, by his late period he had become a “non-traditional Traditionalist”, and the Evolan phraseology deployed by some on today’s radical Right is therefore mostly “post-Traditionalism”.

But logical consistency matters little in politics, even metapolitics. Traditionalism may persist as a presence on the Right, if sometimes more symbolically than as substance. Traditionalists’ emphasis on arcane knowledge is intrinsically appealing to some who aspire to be elite leaders. There are also similarities in outlooks and temperaments between Traditionalists and some Rightists – shared perspectives on the manifold problems of modernity, shared detestation of bleak materialism, and shared love of grand and sweeping narratives. As the once world-bestriding West shivers in winnowing new winds, and mainstream conservatism flounders, the epic appeal of a mythical past (and implied enchanted future) seems likely to grow. Sedgwick’s second book on this too long neglected theme makes another significant contribution to what may be an expanding as well as evolving field.

Book Details: Mark Sedgwick, London: Pelican, 2023, hb., 410pps., £25

My thanks to John Morgan for invaluable input on this article.

Post Views: 1,314 -

How to Deal with an Ideological Villain

A pet peeve of mine is when an antagonist in a book, show, or movie is driven by an ideology that, when he or she is inevitably defeated, nonetheless remains without being dismantled or rendered inept in some way. While, today, it is more often the protagonist driven by his or her writer’s self-inserted worldview, antagonists have, for over a century, often had ideological motivations–saving the climate, achieving some form of racial or sexual (but never ideological) equity, promoting radical resource conservation, whatever. Of course, we keep our hands clean by having the villain nominally lose, but that still leaves the ideology to be dealt with.

If left unanswered, the antagonist’s scheme, though foiled in its dastardly implementation, can too easily become a case of a merely overzealous attempt to produce what some believe to be a nonetheless good, noble goal with whatever hue of progressivism initially drove him or her. The good and the bad becomes, thus, not a matter of principle or goal but of method–the villain or villainess was such because he or she was too radical for those around him or her, etc. Hence, you get people considering whether the Marvel Universe’s Thanos was right in trying to reduce planetary populations by half, whether it wouldn’t be just for Godzilla: King of the Monsters’s Dr. Emma Russel to accelerate some a titanic climate emergency to fully dispense with humanity, or whether X-Men’s Magneto’s openly violent revolution for minority-mutant acceptance wouldn’t be justified–if not just a little satisfying.

Of course, the author who led the way with dealing with explicitly ideological villains was Dostoevsky, who reached his zenith of popularity, not to mention innovation, by dismantling Turgenev’s and Chernyshevsky’s ideological heroes. He did this often through mockery but predominantly through exposing to light of their ideologies through his antagonists who share them. Let us attend: the two–exposure and mockery–can and arguably should go hand-in-hand.

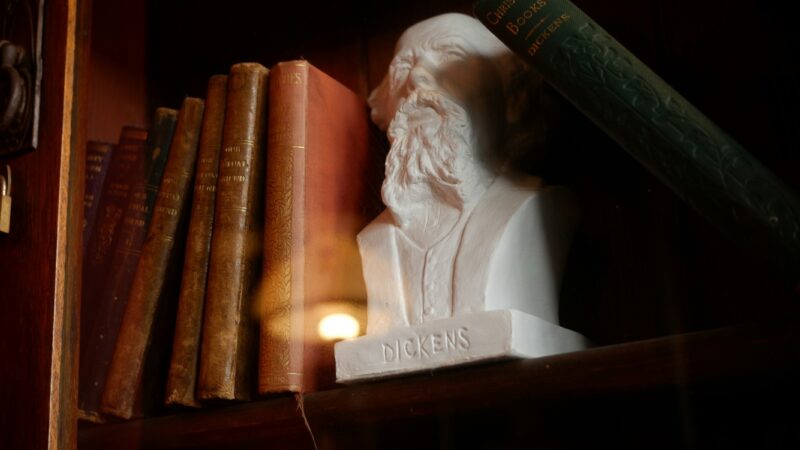

Dostoevsky made it his M.O. to resolve his characters’ conflicts by showing why their motivations are as bad as (or worse than) the attempted implementation. However, there was another writer, up to whom Dostoevsky looked, who was already doing this in England before Dostoevsky hit the Russian literary scene. I am, of course, talking about Charles Dickens.

No reader of Dickens can miss his criticism of the perspectives and politics of his day, be it open scorn, mocking satire, or earnest plea. While not all of his villains recant their ideas, one of his most complete cases of repentance is also one of his most popular tales, especially come Yuletide. This is none other than A Christmas Carol.

Now, readers will not need me to review the plot of Ebenezer Scrooge, whose name has become synonymous with Christmas in the English-speaking world. However, I nonetheless want to briefly examine points in Scrooge’s arc to see how it is not only his avarice but also the then popular ideology that justified it that is defeated in the end. Dickens pretty handily sets up the contemporary pop philosophy that gilds Scrooge’s greed. Rejecting personal charity for the impersonal, tax-funded state institutions of ‘“prisons…Union workhouses…the Treadmill and the Poor Law,”’ he identifies himself in the first scene as a Social Darwinist and Malthusian Utilitarian. ‘“Christian cheer of mind or body to the multitude,”’ as one of the scene’s collectors of charity puts it? Bah–humbug! ‘“I help to support the establishments I have mentioned,”” he says, ‘“they cost enough; and those that are badly off must go there…If they would rather die…they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”’ In Scrooge, Dickens concretises the worst versions of the ideologies gaining popularity as an increasingly rationalistic society dispensed with Christian superstitions of God’s image in each individual, and with them the Christian ethics behind giving of one’s own to the poor.

Of course, Dickens includes us in the dramatic irony that Scrooge’s integrity is neither admirable nor monstrous (yet), but pitiable and foolish. The former is articulated when, drawn through key moments of his past by the Ghost of Christmases thereof–his lonely Christmases as a child, his little sister who would leave behind his supposedly foolish nephew, his erstwhile love for the Christmas season at Old Fezziwig’s regardless of its cost in ‘mortal money’–Scrooge is reminded of how spectacularly he fumbled the bag with his fiancée Belle by grasping a different bag too tightly. The enlightened self-righteousness of Scrooge’s post-Christian ethic is neither as internally consistent nor as impressive as its holder might try to maintain: juxtaposing Scrooge’s excited apology for Fezziwig’s party in spite of himself with an unwillingness to look on the greed that would lead to his present loneliness, Dickens makes clear that Scrooge’s ideological righteousness covers a deeply buried sense of failure, regret, and betrayal of the best aspects of his past self. The scene shakes Scrooge’s supposedly staid principles, and his explicit and implicit admissions that gold is not the be-all, end-all valuer of life serve to begin his reformation.

Having shown why Scrooge is to be pitied for his Malthusian views (which he may not even fully hold), Dickens progresses to show Scrooge that he has also been unnecessarily foolish to hold them. Satisfying the first scene’s foreshadowing, this foolishness is shown when the Ghost of Christmas Present gives us more of his nephew, Fred.

Hard on the heels of shaming Scrooge with the mistreated Bob Cratchit’s nonetheless toasting him, the second Ghost presents Fred’s dinner party, sans uncle. Whereas Cratchit politely rebuffed his wife’s insults to Scrooge, Fred does the same to his wife’s with jollity. ‘“His wealth is of no use to him. He doesn’t do any good with it.”’ When his wife says, ‘“I have no patience with him,”’ Fred returns:

‘“Oh, I have!…I am sorry for him: I couldn’t be angry with him if I tried. Who suffers by his ill whims? Himself, always…[The] consequence of his taking a dislike to us, and not making merry with us, is, as I think, that…he loses pleasanter companions than he can find in his own thoughts, either in his moldy old office or his dusty chambers. I mean to give him the same chance every year, whether he likes it or not, for I pity him.”’

The girls mock the idea of Scrooge’s ever taking Fred up on that chance. However, unbeknownst to them, their mock unknowingly digs the knife of change further into the invisible uncle–not by disclaiming the immorality of his avarice (which might harden him), but by showing how foolish he is to maintain his proud isolation in it.

And the fact is that Scrooge would much rather be with them. In spite of himself, he tries his invisible darnedest to play along with the group’s games, which leads him, unsuspectingly, into being the butt of the night’s climactic joke. Having already shown Scrooge the ineffectuality of his gold and spite, Dickens meets both not with other characters’ argument but with mockery. Little wonder that the later Dostoevsky, who would mock his characters while showing the disastrous real-world consequences of their ideas, counted Dickens as one of his primary influences.

And yet, Dickens does not risk leaving things there, for one man’s pitiable past and foolish present might not undermine an entire ideology, even to the man himself. Before he leaves, the second Ghost reveals to Scrooge the true nature of his ideas–in the forms of the emaciated siblings, Ignorance and Want, hidden beneath his heretofore abundant cloak. ‘“Scrooge started back, appalled. Having them shown to him in this way, he tried to say they were fine children, but the words choked themselves, rather than be parties to a lie of such enormous magnitude.”’ Pushed to choose between the utilitarian phrases of his ideology and his own human sympathy, Scrooge ultimately cannot utter the former.

Readers don’t need me to review Scrooge’s interview with the third Ghost. Suffice it to say, his initial viewpoint, if followed through, will land him little posthumous respect among the living, even those who nominally venerate the old skinflint. Furthermore, to add insult to injury, with none to care for his affairs, Scrooge’s possessions will land in the hands of petty thieves–who, as a last insult to his way of life, parody him in their penny pinching over his personal effects. In death, he is treated according to the utilitarian ideology he espoused in life.

Now, several moments in A Christmas Carol are, without a doubt, moralistic and even a bit preachy in dealing with Scrooge’s ideology (example, the two waifs, above), and can, thus, arguably be skipped in retellings or depictions without the story’s–or Scrooge’s humbling’s–losing much weight. As I have previously written on the story, the falling away of such excesses, bound as they are to ideas and issues contemporary to its writing, is the beginning of a work’s usefulness as art. That so much of A Christmas Carol remains despite its initial polemic speaks to Dickens’s ability to make a point without its feeling like he is doing so.

And yet, his depiction of Social Darwinism remains relevant–not the least because Scrooge’s hardnosed display foreshadows those in our own day who promote state redistribution schemes while foregoing personal charity, yet somehow still thinking themselves moral and on the side of the poor. Furthermore, current progressive ideologies often take on the same self-satisfied tone, even glee, as Scrooge at the supposedly justified handicap or destruction (always their fault) of the designated outgroup–white men, “the rich,” landlords, heteronormative family units, groups indigenous to European lands, etc. Their hijacking every medium they can for the sake not of creating good art but of spreading “The Message” has left a dearth of art and stories that seek not only to include the majority of audiences but also to simply be good for their own sake. The question among conservative creators (which, as I argue in the above linked article, not to mention my novel, includes many more than those who consider or label themselves conservative) of how to create the best art can and should point us to authors like Dickens and Dostoevsky.

While politics was not the point for such authors, they did not shy away from dealing with insidious ideas of their day. The difference between them and authors who see art as inherently political was and should be that, in treating art as a function of greater things than politics–not to mention weighing it against human experience and tradition–they exposed inhuman ideas fully in the lives of their characters. Such a thing necessarily leads, as can be seen in A Christmas Carol, towards at least some characters’ repenting of their ideology towards a more wholistically human ethic that balances personal rights and interests with duties and responsibilities for others–one I would argue is best found in the Christian view of man and its subsequent moral tradition, articulated implicitly in Dickens and explicitly in Dostoevsky.

Like many pre-20th-century books, A Christmas Carol is refreshing, if nothing else because its lesson is for its protagonist (who is also its antagonist), not its readers, who are included in the joke. However, even thus reducing it to a “lesson” is to render it as inhumanly provincial as is the pre-repentance Scrooge. We should look to older literature not just to nostalgically escape the present (though that’s often a necessary salve), nor to learn how to “retvrn” to a time before all the other advancements our culture has made (on the backs of the previous centuries’ literature and ethics, one should add). We should do so because older books have survived the changing of times.

Said survival is not, as Marxist progressives claim, because their popularity has been artificially and oppressively maintained in various social traditions and structures (though one man’s supposedly oppressive structure might be many other men’s most efficient means of justly and safely ordering society). Rather, it is because their authors concretised elements of human life that are and will remain immutably true. That, of course, can have implicit ideological or political (etc.) ramifications, but such accidental effects are not their core substance. Watching a rendition of A Christmas Carol to get into the Christmas spirit might have the effects of motivating us to give to the less fortunate or to look, Cratchit-like, with forgiveness on even the most oppressive of our fellow men (or on ourselves, as Scrooge, himself, learns to do). However, to see this kind of thing as inherently political or ideological is, itself, to maintain an ideology about the relationship between art, actual people, and each other that would reduce all three. Thankfully, should we want to dismantle such a thing, we know where to look.

Post Views: 542 -

Immaturity as Slavery

“… but I just hope the lad, now in his thirties, is not living in a world of secondhand, childish banalities.” – Sir Alec Guinness, A Positively Final Appearance.

The opening quote comes from a part of Alec Guinness’ 1999 autobiography which greatly amuses me. The actor of Obi Wan Kenobi is confronted by a twelve-year-old boy in San Francisco, who tells him of his obsessive love for Star Wars. Guinness asks if he could do the favour of “promising to never see Star Wars again?”. The lad cries, and his indignant mother drags him away. Guinness ends with the above thought. He hopes the boy is weaned from Star Wars before adulthood, lest he become a pitiful specimen.

Here enters the figure of the twenty-first century man-child, alias the “kidult”. He’s been on the radar for a while. Social critic Neil Postman prophesies the coming of “adult-children” in The Disappearance of Childhood from 1982. American journalist Joseph Epstein calls this same creature “The Perpetual Adolescent” in a 2004 article of the same name. But the best summary of this character I’ve yet found is by the writer Jacopo Bernardini, from 2014, to which I can add but little.

The kidult is one who lives his life as an eternal present. As the name suggests, his life is a sort of permanent adolescence. He is sceptical of traditional definitions of adulthood, so has deliberately shunned milestones like marriage and childbearing, in favour of an unattached lifestyle which lasts indefinitely. His relations with other people remain short and shallow; based entirely on fun and mutual use (close friendships or passionate love-affairs are not for him).

Most importantly, the kidult doesn’t change his tastes or buying habits with age. The thresholds of adolescence and maturity have no bearing on the things he likes and purchases, nor how he relates to these things. Not only does he like the same toys and cartoons at thirty as he did at ten, but he continues to obsess over them and impulsively buy them like when he was ten. Enjoying childhood fare isn’t a playful interlude, but a way of life which never ends. He consumes through instant gratification, paying no thought to any long-term pattern or goal.

Although it must not strike the reader as obvious, I think there exists a link between Guinness’ “secondhand, childish banalities” and a kind of latter-day slavery. To see the link needs some prep work, but once laid, I think the reader will see my point.

First to define servility. I believe the conservative writer Hilaire Belloc gave the best definition, and I shall freely paraphrase him. The great mass of people can be restricted yet not servile. Both monopolistic capitalism and socialism reduce workers to dependency, but neither makes them entirely slaves. Under capitalism, society retains an ideal of freedom, enshrined in law. Even as monopolists manipulate the law with their money, the ideal remains. Under socialism, state ownership is supposed to give all citizens leisure to do what they want (even as the state strangles them). In either case then, freedom is present as an ideal in theory even as it ceases to exist in practice. Monopolistic and socialist states don’t think of themselves as unfree.

Slavery is different. A slave society has relinquished even the pretence of freedom for a large mass of the working people. Servility exists when a great multitude are forced to work while having no productive property, and no economic independence. That is, a servile person owns nothing (or effectively nothing) and has no choice whatsoever over how much he works or for whom he works. Most ancient civilisations, like Egypt, Greece, and Rome were servile, with servility existing as a defined legal category. That some men were owned by others was as enshrined by law as the ownership of land or cattle.

Let’s put a little Aristotle into the mix. There are two kinds of obedience: from a free subject to a ruler, and from an unfree slave to his master. These are often confused but distinct. For while the former is reasonable, the latter involves no reason and is truly blind.

True authority is neither persuasion nor force. If an officer argues to a soldier why he should obey, then the two are equals, and there’s no chain of command. But if the officer must hold a gun to the man’s head and threaten to execute him lest he do his duty, this isn’t authority either. The soldier obeys because he’s terrified, but not because he respects his superior as a superior. True authority lies in the trust which a subordinate has for the wisdom and expertise of a superior. This only comes if he’s rational enough to understand the nature of what he’s a part of, what it does, and that some people with knowhow must organise it to work properly. A sailor understands he’s on a ship. He understands that a ship has so many complex functions that no one man could know or do them all. He understands that his captain is a wiser and more experienced fellow than he. So, he trusts the captain’s authority and obeys his orders.

I sketch this Aristotelian view of authority because it lets us criticise servility without assuming a liberal social contract idea. What defines slavery isn’t that the slave hasn’t chosen his master. Nor that the slave doesn’t get to argue about his orders. A slave’s duty just is the arbitrary will of his master. He doesn’t have to trust his master’s wisdom, because he doesn’t have to understand anything to be a slave. That is, while a soldier must rationally grasp what the army is, and a citizen must rationally grasp what society is, a slave is mentally passive.

Now, to Belloc’s prophecy concerning the fate of the west. The struggle between ownership and labour, between monopoly capitalism and socialism, which existed in his day, he thought would result in the re-institution of slavery. This would happen through convergence of interests. The state will take an ever-larger role in protecting workers through a safety net, that they don’t starve when unemployed. It will nationalise key industries, it will tax the rich and redistribute the wealth through welfare. But monopolies will still dominate the private sector.

Effectively, this is slavery. For the worker is protected when unemployed but has entirely lost the ability to choose his employer, or even control his own life. To give an illustration of what this looks like in practice: there are post-industrial towns in Britain where the entire population is either on welfare or employed by a handful of giant corporations (small business having ceased to exist). To borrow from Theodore Dalrymple, the state controls everything about these people, from the house they inhabit to the school they attend. It gives them pocket-money to spend into the private sector dominated by monopolies, and if they want to work, they can only work for monopolists. They fear neither starvation nor a cold night, but they have entirely lost their freedom.

This long preamble has been to show how freedom is swapped for safety in economic terms. But I think there’s more to it. First, the safety may not be economic but emotional. Second, the person willing to enter this swindle must be of a peculiar mindset. He must not know even a glimmer of true independence, lest he fight for it. A dispossessed farmer, for example, who remembers his crops and livestock will fight to regain them. But a man born into a slum, and knowing only wage labour, will crave mere safety from unemployment. Those who don’t know autonomy don’t long for it.

There now exist a troop of companies that market childish goods for adult consumption. They typically do this in one of two ways. First, offering childish products to adults under the guise of nostalgia. The adult is encouraged to buy things reminding him of his childhood, with the promise that he will relive it. Childish media and products are given an adult spin, and remarketed. Toys are rebranded as collectibles. Children’s films get unnecessary, adult-oriented, sequels or remakes (what Bernardini calls “kidult movies”). Originally child-friendly festivals or theme parks are increasingly marketed to childless adults.

The second way is by infantilising adult products. Adverts, for example, have gradually replaced stereotypical busy office workers and exhausted housewives with frolicking kidults. No matter how trivial, every product that is not related to Christmas, is now surrounded by giddy, family-free people engaged in play. The message we’re meant to get is that the vacuum cleaner or stapler will free us to act like children. By buying these things, we can create time for the true business of life: bouncing and smiling with one’s mouth open.

I believe infantilism to be a kind of mental slavery. In both the above examples, three elements combine: ignorance and mass media channel anxiety into childishness. This childishness then binds the victim in servitude to masters who take away his freedom while robbing him in the literal sense.

An artificial ignorance created by modern education is the first parent of the man-child. Absent a proper and classical education, the kidult’s mind is an empty page. Lack of general knowledge separates him from the great achievements of civilisation. He cannot seek refuge in Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, or Dante, for he has never heard of these. He cannot draw strength from philosophy and religion for the same reason. Neither can he learn lessons from history, for the world begins only with his own birth. Here is a type of mental dispossession parallel to an economic one. Someone utterly ignorant of the answers great people have given to life’s questions will seek only safety, not wisdom.

The second parent is anxiety. Humans have always been terrified of the inevitable decay of their own bodies, followed by death. The wish for immortality is ancient. Yet the modern world, with its scepticism, creates a heightened anxiousness. When all authority and tradition has been deconstructed, there is no ideal for how people ought to live. Without this ideal, humans have no certainty about the future. Medieval people knew that whatever happened, knights fought, villeins worked, and churchmen prayed. Modern man’s world is literally whatever people make of it. It may be utterly transformed in a very short time. And this is anxiety-inducing to all but the most sheltered of philosophers.

Add to this the rise of a selfish culture. As Christopher Lasch tells us, the nineteenth century still carried (in a bastardised way) the ideal of self-sufficiency and virtue of the ancient man. Working and trading was still tied to one’s flourishing in society. Since 1960, as family and community have disintegrated, the industrialised world has degenerated into a Hobbesian “war of all against all”. A world of loneliness without parents and siblings; lacking true friends and lovers. When adulthood has become toxic and means to swim in a sea of disfunction, vulgarity, substance abuse and pornographic sexuality; it’s no surprise some may snap and long for a regression to childhood.

Mass media is the third condition. It floods the void where education and community used to be. The space where general knowledge isn’t, now gets stamped by fiction, corporate advertising, and state propaganda. These peddle in a mass of cliches, stereotypes, and recycled tropes.

My critique of kidults isn’t founded on “good old days” nostalgia, itself a product of media cliches. Fashions, customs, and culture change; and the citizen of today doesn’t have to be a joyless salaryman or housewife to count as an adult. Rather, the man-child phenomenon is a massive transfer of power away from the small and towards the large. The kidult is like an addict, hooked on feelings of cosy fun and nostalgia which are only provided by corporations. These feelings aren’t directed to the good of the kidult but the organisation acting as a dealer. The dealer controls the strength and frequency of the dose to get the wanted behaviour from the addict.

Now we see how kidults can be slaves. First, they’ve traded freedom for safety (false as it is) like Belloc’s proletarians made servile. Unlike the security of a traditional slave, this is an emotional illusion. The man-child believes that there’s safety in the stream of childish images offered to him. He believes that by consuming these the pain of life will cease. Yet man-children get no material or mental benefit from their infantilism. Indeed, they’re fast parted from their money, while getting no skills or virtues in return. The security is merely psychological: a Freudian age regression, but artificially created.

Second, while authority in Aristotle’s sense means to swap another’s judgement for your own, for the sake of a common good you understand; here you submit to another’s judgement for the sake of their private good, which you don’t understand. Organisations seeking only profit or power impose their ideas on the kidult, for their benefit. An immature adult pursues only pleasure, lives only for the present, and thinks only in frivolous stereotypes and cliches implanted during childhood. He’s thus in no position to understand the inner workings of companies and governments. He follows his passions like a sentient puppet obeying an invisible thread, leading always to a hand just out of sight.

In the poem London, William Blake talks about “mind-forg’d manacles”. These are the beliefs people have which constrain their lives in an invisible prison of sorts. For what we think possible or impossible guides our acting. Once mind-forg’d manacles are common to enough people, they form a culture (what’s a culture if not collective ideas on how one should act?). Secondhand childish banalities are such mind-forg’d manacles if we let them determine us wholly. Their “secondhand” nature means the forging has been done for us, and this makes them more insidious than ideas of our own creation. For if what I’ve said above is true, they threaten to make us servile. If enough people become dependent on secondhand childish banalities, as the boy who met Alec Guinness, then the whole culture becomes servile. Growing up may be painful, but it’s a duty to ourselves, that we remain free.

Post Views: 974