With the recent debates surrounding AI improvement and the somewhat imminent AI takeover, I thought it would be interesting to return to the 20th century to analyse the debates on the rise of the machine and what we can learn from it today.

The early 20th century marked a time when the technological revolution was in full swing. With radio, mechanised factory work, and the First World War marked the new era of mechanised warfare, the intellectuals of the day were trying to make sense of this new modernised society. With the speed at which the changes occurred, people’s conception of reality was lagging.

The machine has narrowed spaces between people – the car allowed people to traverse space faster, and radio and telephone brought closer and practically instantaneous access to one’s family, friends, and acquaintances. The jobs were mechanised and people, as idealised by Marx, had the potential of being the ‘mere minders of the machine’. We are now entering another era. A time when Artificial Intelligence has the potential to replace most jobs. This is what Fisher in Post-Capitalist Desire has considered an opportunity for a post-scarcity society. But is this possible? Or rather should we heed Nick Land’s warning in Machinic Desire where he advised:

“Zaibatsus flip into sentience as the market melts to automatism, politics is cryogenized and dumped into the liquid-helium meatstore, drugs migrate onto neurosoft viruses, and immunity is grated-open against jagged reefs of feral AI explosion, Kali culture, digital dance-dependency, black shamanism epidemic, and schizolupic break-outs from the bin.” (Land, Fanged Noumena, 2011)

But let’s thrust away the shatters of this neo-automation and return to 1912, the time when this has only just begun.

Gilbert Gannan, in an article for Rhythm, wrote:

“Life is far too good and far too precious a thing to be smudged with mechanical morality, and fenced about with mechanical lies, and wasted on mechanical acquaintanceships when there are splendid friendships and lovely loves in which the imagination can find warm comradeship and adventure, lose and find itself, and obtain life, which may or may not be everlasting.” (Gannan, 1912)

In a quasi-perennial argument, he claims that mechanical morality and mechanism, in general, will never replace the real deal – the real concrete friendships and those we love.

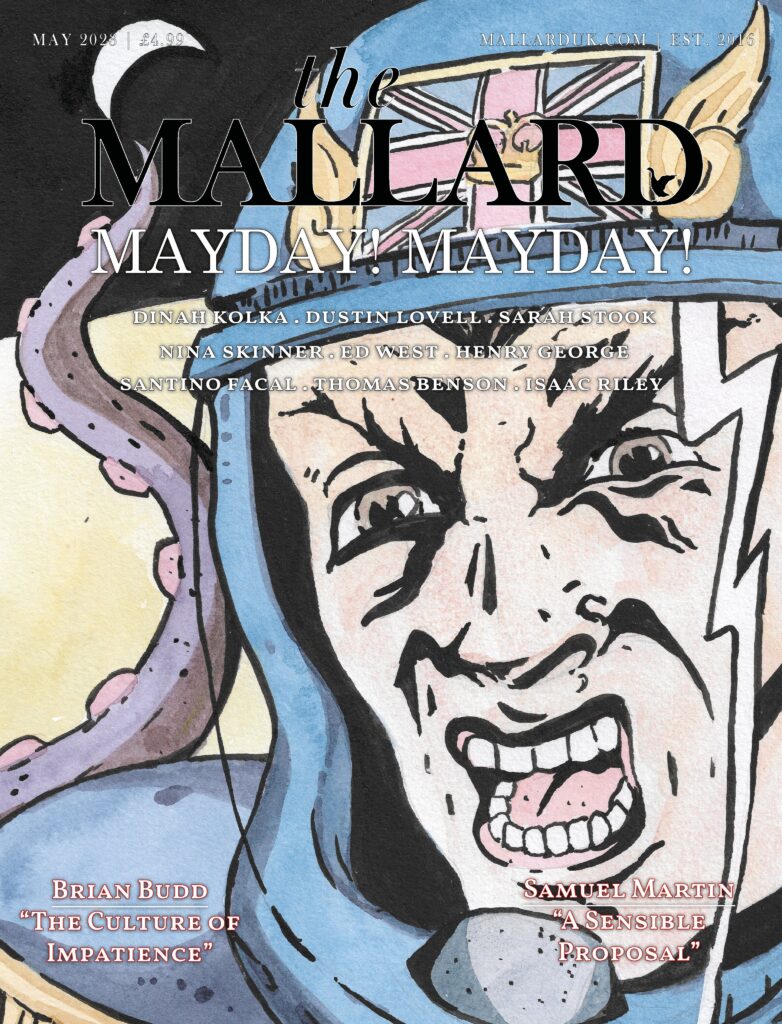

This is an excerpt from “Mayday! Mayday!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

You Might also like

-

Conservatives Just Don’t Get It

This article was originally published in April 2020.

“It is always said that a man grows more conservative as he grows older; but for my part, I feel myself in many ways growing more and more revolutionary” – G.K. Chesterton.

One should never attempt to fight the enemy on his home turf. Unfortunately, conservatives have been doing exactly that for the past 60 years. The changes to the social fabric that have occurred over decades, courtesy of the left’s dominance on the cultural front, have been nothing short of extreme. Such changes are paramount to an intergenerational sociocultural revolution, one which many “conservatives” refuse to acknowledge the significance of, either due to ignorance, arrogance, or cowardice.

Some would rather indulge in the rather fashionable practice of vacuous contrarianism, insisting that the concept of “Culture War” is trivial; imported for the sake of disruption rather than anything important. I can assure you, it’s not. Despite the coronavirus pandemic, our politics continue to no longer be defined by the material and the necessities for survival. Nor is it defined by the intricate details of policy papers. Rather, it is fundamentally cultural; it is an existential conflict, one which has emerged amid the increasingly different ways we define who we are. Far too many conservatives underestimate the importance of this fact. Far too many conservatives just don’t get it.

Defining the Enemy

The most common understanding of the left is the left-wing party. Naturally, in Britain, the Labour Party comes to mind. It’s those socialist maniacs who want to raise your taxes, bankrupt the country, and bring back the IRA. To some extent or another, this may or not be true. Some may be (correctly) willing to push the boat out and incorporate other parties such as the Liberal Democrats and the SNP into this understanding. Whilst they incorporate different ideological strands into their party platforms (i.e. liberalism, Scottish nationalism, etc.) they are still understood as belonging to the broadly progressive, left-of-centre bloc of British politics. Of course, this excludes the Conservatives themselves, not because they’re right-wing, but because they are not ‘officially’ seen as such.

However, specifically in the scope of culture, “the left” has historically been encapsulated in (as one in the midst of China’s own cultural revolution would put it) the hatred of “old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas”. It is the movement which not only holds these things in contempt, but has artificial over the course of several generations, actively sought to undermine them, and supplant them with placeholders. Whether it is branded as liberation or social justice, deconstruction or decolonisation, the motive is the same: the eradication of Britain’s true understanding of itself. It is the removal of a nation’s identity, onto which another one can be projected; one that serves the interests of the revolutionaries, who have long since been assimilated into positions of officialdom. Tradition, in all its forms, is not a milestone of progress to these people, but something which stands in its way. Tradition are markers of oppression, bigotry, and other devalued soundbite terms that have long infested modern politico-cultural discourse.

This outlook, when put into perspective, is hardly contained within the confines of mainstream political parties. On the contrary, the most ardent advocates and enforcers of these ideas do not have a seat in parliament or hold a party membership card, yet they still wield extraordinary amounts of influence over the public realm, either as well-known figures or grey eminences. If conservatives are to get serious about conserving, they will have to think outside the party-political box and engage with the wider political arena; the Labour Party is merely one of many heads of the progressive hydra that has been wreaking havoc on our country.

The Conservative Problem: The World Moves On

So often, mainstream conservative figures evoke the Devil-like image of Marx, whose communist ideals linger within the minds of leftists. This is often done with the hope of incentivizing the public to steer clear of such people. This poses two problems. One is that most people (especially young people) really don’t care about the “threat of communism”. They may find the CCP distasteful, they may prefer the USA as the world hegemon, but people (again, especially young people) don’t have a potently adverse reaction to communism. Keep in mind, this general sense of apathy is also felt towards other historically charged political forces, such as the IRA, Hamas, and Venezuelan Socialism. Indeed, one could say the same thing about National Socialism, but I digress.

Too many conservatives fundamentally misunderstand of the type of left we are up against, not just in the party-political sphere but in all nooks and crannies of every institution of society. If you want to understand the grotesque and underhand nature of modern leftism, you’re better off the intellectual descendants of Marx, rather than Marx himself. Whilst Marx called for the proletariat to revolt against their bourgeoisie oppressors, Gramsci fixated on the issue of cultural hegemony – that economic transformations can only occur if a society is preconditioned with the necessary cultural values; it is these cultural values that justify whatever economic system is in place, and by extension, the specific nature of economic redistribution. Conservatives can hardly hope to win if they can’t even recognise the type of battle that’s being fought which is, first and foremost, one of a cultural nature.

Politics is Downstream from Culture

Supremacy in Parliament is important; it is the sovereign legislature after all. However, conservatives must remember that power, in all its forms, transcends the walls of Westminster; capturing the building where legislation is made must be combined with capturing the institutions that shape our nation’s political “Overton Window”. It is this framework that inspires the legislation that is created within it and dictates what legislation can exist. If legislation isn’t allowed to exist in a ‘culturally appropriate’ sense, then it almost certainly won’t be allowed to exist in a practical sense.

Conservatives must reaffirm themselves with the timeless truth that “politics is downstream from culture”. Politicians are important actors, but they are not the only actors. Conservatives must learn to march through the institutions as the left has done for so many years with frightening efficacy, whether it be in the classroom or the court room, the media or the civil service, the hospitals or the churches. It is victory on this front that has already altered the perceptions we have of our society, and therefore how we conduct our politics.

Currently, the products of these institutions are often laced and ingrained with progressive preconceptions and cultural attitudes. Dissenting views and sentiments are purged from the circles that produce these mass-consumed cultural products. This is not because they are wrong in any objective sense, on the contrary, many have realised that what’s said in these instances is actually pretty milquetoast (“trans women aren’t biological women, etc.). People’s politics are shaped by the environment in which they operate, and as time has gone by, the leftist-domination of seemingly neutral institutions has resulted in those who would otherwise being apolitical becoming (either explicitly or implicitly) averse or straight up hostile to conservatism. Then again, why shouldn’t cultural progressives do this? They have shown time and time again that they cannot (currently) advance their ideas via the ballot box, so instead they focus on maintaining and integrating their power where it already exists and doing what they can from there.

Conservatives are foolish if they think that they can ignore the concerns of people until they reach 30. Whilst young conservatives are more radical than their elders, they are fewer in number. Young people are far more hostile to conservatism than 40 years ago, and older people are becoming increasingly progressive themselves. The demography is against us, in more ways than one. They may not call for the workers of the world to unite, but they still hold disdain for those who hold socially traditionalist sentiments. The Conservative Party can win as many elections as it likes, but it won’t matter provided culturally conservative ideas are suppressed and forced to remain on the fringes. The electorate may not be averse to the Party, but as for the philosophy from which it draws its name, that a very different kettle of fish.

The Conservative Problem: Parliament is the Ultimate Prize

Despite all this, it is hard for many in the Conservative Party to comprehend how “the left” continues to be an existential threat to the British and our way of life. When I converse with Conservative Party members, many often exalt over “Bojo winning a stonking 80 seat majority and saving Britain from the clutches of Red Jezza”. Once again, the problem with this is that it reduces the political to party politics, electoral success, and the squabbles of Westminster and Tory Twitter. It also severely underestimates the vehicle for change an 80-seat majority could act as provided we addressed the current cultural paradigm in which the party is forced to operate. A cultural paradigm that will only continue in the favour of progressives provided conservatives get their act together.

Unfortunately, anytime someone within the ranks of the party dares to defend Britain from continuous desecration besides the safe stuff, such as the monarchy and purely liberal-democratic interpretations of Brexit, much like the spiteful and monotonous Marxist-drones thy insist to be so different from, they hound you, assassinate your character, declare you unfit for public life. To not sufficiently submit to the brand of “Conservatism” permitted by the current cultural paradigm is often nothing short of social suicide. This also goes for those who espouse their profusive love for the “broadchurch” and talk about free-thinking with impassioned vigour, like some firebrand philosopher from the enlightenment. Then again, one should expect such two-faced behaviour from careerist sycophants. For the overwhelming number of apparatchiks, patriotism is just for show.

This is not to say supporting the monarchy and Brexit are bad things. On the contrary, I am a monarchist (although, I am not a Windsorian) and favoured Brexit before Brexit was even a word. What should be noted though is that to truly prevent Britain’s abolition, we must do so much more. This “do what you like so long as it doesn’t affect my me or my wallet” mindset is deeply ingrained into our society, even in its economically downtrodden state, inhibits the political conscience we require for national renewal.

Of course, there have been “attempts” by “culturally conservative” minded individuals to engage in cultural discourse. Pity they rarely talk about anything cultural or conservative. Normally its either some astroturfed rhetoric about the wonders of free-market capitalism and individualism, and the menaces of socialism and big-government. When they do, it’s nothing more than them desperately trying to prove to their left-leaning counterparts that they’re “not like those other nasty Tories” or that it “it’s actually the Left that is guilty of [insert farcical modern sin here]”. I look forward to living in the increasingly cursed progressive singularity in which leftists and “rightists” are arguing over who’s more supportive of drag-queen story time, mass immigration, and open-relationship polyamory. What’s more, attempts to indoctrinate the youth into becoming neoliberal shills could be more forgivable if their attempts weren’t teeth-grindingly cringey.

The Mechanics of Political Discourse

The mainstream media, for example, is one of many institutions dominated by cultural progressives, has long perpetuated the façade of meaningful politico-cultural discourse. How many times have we seen a Brexiteer and a Remainer go head-to-head on talk shows and debate programs only for it to be a session of who can come across as the most liberal and globalist? “Brexit is a tragic isolationist, nationalist project” pathetically weeps the [feckless and unpatriotic] Remainer. “No no, it is THE EU that is the isolationist, nationalist project!” righteously proclaims the [spineless and annoying] Brexiteer. These people talk as if the British populace have all unanimously agreed that therapeutic-managerialism is currently the best thing for their country. As much as the grifters and gatekeepers might like to ride the “reject the establishment, stand up for Britain” wave to boost their online clout, they’re just as detached from the concerns and problems facing Britain as “those damn brussels bureaucrats” and “out-of-touch metropolitan lefties”. As a Brexiteer you’ll have to forgive my mind-crippling ignorance, but I am highly suspicious of the idea that most Leave voters sought to accelerate the effects of economic and cultural globalisation. Brexit, by all measures, drew the battle lines between the culturally conservative Leavers and the culturally liberal Remainers (individual exceptions accounted for).

This influence must not be taken lightly, even the most authoritarian regimes must rely on some consent and co-operation from forces beyond the central government. Not the people of course, but those who assist it in the government’s ability to govern; an all-encompassing apparatus through which a government may be permitted to assert its influence; comprised of NGOs, QUANGOs, the civil service, the mainsteam press, and various directly affected sections of society with vested interests in the form of corporate monopolies, universities, and devolved bodies. Without support and co-operation from these institutions, a government’s ability to exert influence is drastically limited. It is from these non-parliamentary sources of influence that have come to possess substantial (and practically unaccountable) amounts of power over the politico-cultural discourse. They decide what questions exist, what topics are taught, how issues are discussed, what viewpoints get publicity, what projects receive funding, what subjects’ officially matter… they decide what’s funny, and what’s not!

The cultural values at the top of society, and therefore endemic to society as a whole, lend themselves both to the creation of a cohesive ruling class. One with capabilities so indispensable to government that even if a party were to capture power on a conservative platform, it likely wouldn’t make all or most of the necessary changes needed. It also makes those values assume a special worth that other cultural attitudes do not have. Like all such “sacred” values, they do not exist in a single place, they permeate out as both a civilisation’s assumed-to-be natural moral standards and as something which exists at the top of socio-cultural hierarchy of status.

The Conservative Problem: The Rules are Fair

Considering what is a highly restrictive discourse, many will shake their fist and declare “you just can’t say anything these days”. Total rubbish. You just say certain things. You can say that mass-immigration is a blessing. You can say we should normalise dating sex workers. You can’t say anything meaningful about the nationwide grooming gangs or “I personally believe {insert any run of the mill socially conservative view here}. If you do, you’ll end get fired from your job, or the Church of England and be forced to issue a grovelling and humiliating press-mandated apology for harbouring remnants of Christian sentiment. The New Statesman-lead character assassination of the late and great Sir Roger Scruton, a smear campaign by the media that continued even after his death, is a rather poetic embodiment of the conservative situation. The great irony of liberalism is debating whether one should tolerate those with alternative attitudes (regardless of how illiberal) or utilise the power of institutions to force those people to adopt liberal ones, explicitly or implicitly. As one would expect, vast majority of liberals in recent years have selected the latter. Openness must be secured through the exclusion of those that demand exclusion, which neccesarily narrows the scope of politics.

Unfortunately, despite cultural leftists wanting to eradicate them for political life, conservatives still see themselves as above obtaining and using power. Again, they’ll try their hardest to win an election, but when it comes to actively supporting the defence and furtherance of conservative values they’d much rather not be involved. At most they’ll shake their heads at those crazy progressives with their wacky pronouns and move onto the next Twitter controversy. Of course, power is not the only thing of value in this world, but is neccesary asset if you want your principles to actually mean something. It is hardly a sufficient response to throw your hands up and declare yourself above the fight. If anything, it’s the acknowledgment of this reality that makes people conservatives in the first place.

On Counter-Revolution

A cultural counter-revolution is possible. However, it will require conservatives coming to terms with their new roles, not as protectors of the status quo, but as those who are reacting to the increasing perversity, corruption, and sclerosis of the new order. The struggle will be long but that it is the only way it can be. Efforts to conserve our future must begin in the present, even if we look to the glories of the past for inspiration.

Many will not stand as they do not have a conservative bone in their body and are in themselves part of the problem. Others will be defiant about taking a stand at all. They will self-righteously declare:

“I’m not choosing a side. I want nothing to do with this. It’s got nothing to do with me!”

Unfortunately for them, the choice to be apathetic about the destruction of your civilisation is still a choice. Many haven’t clocked that politics is not only a never-ending war, but an unavoidable one; one which we are losing, with consequences mounting with every generation.

Of course, a lot of conservative activists are like me. We are not just Conservatives in the sense of party membership, we are instinctually conservative. We came to the Conservative Party because, despite the self-interested careerists and the severe shortcomings in policy in recent years, we recognised that the party itself serves a fundamental role in making our voices heard. As much as liberals in the party would like to throw us out by the scruff of our necks, one can only deny social conservatives their rightful place within the Conservative Party for so long.

Although I must say, I was hoping that a party with an 80-seat majority would have more vitality than a freshly neutered dog. Far too many Conservatives would prefer the party to be an over-glorified David Cameron appreciation club, or the parliamentary wing of the Adam Smith Institute, rather than the natural party of Britain. A Conservative Party that supports conservatism will not alone be enough, but it will be necessary, The Conservative – Labour/Liberal dichotomy is so ingrained in British politics that an alternative right-wing is likely to fall flat, even when there may be demand for one.

I am sure we are not small men on the wrong side of history. However, should I be wrong, I have the benefit of being young and naïve. I have come to terms with being an argumentative, nationalistic Zoomer and I’m far too stubborn to give up on my ideals, especially at this stage in my life. The fire of counter-revolution must not be extinguished, it must be passed down.

My fellow rightists, you can continue leading the life of a cringe, narrow-minded normiecon; begrudgingly submitting to apparatchiks, gatekeepers, and controlled opposition; parroting every stale, uninspiring, mass-produced talking point to inoculate against the turbulence of politics. Alternatively, you can break your chains and take Britain’s destiny into your hands.

Post Views: 788 -

Notes on the Social Democratic Party Conference

Upon arriving at Church House, I was asked for my name so I could receive my pass. I wasn’t on the list. After a few brief minutes, assuring the two very kind activists working the reception that I wasn’t a militant infiltrator, it turned out that I was on a completely different list – the VIP list. Jesus Christ, I thought, the Conservative Party never gave me a VIP pass!

Making my way up the stairs to the conference hall, I walked in on the SDP membership voting on various motions; policy proposals that may or may not be adopted into the party platform. The Labour Party is hated for a variety of valid reasons; I would know, I tend to hate them for such reasons myself. That said, one of the benefits of being a Labour member, compared to being a member of the Tory Party, is the ability to influence policy through voting. Unfortunately, it comes with a catch: sharing a party jampacked with gay race communists.

Conventional wisdom tells us that we cannot have our cake and eat it, but the SDP provides a pretty compelling counterargument. You can have a democratic party, one which gives people some degree of political influence in exchange for paying the membership fee, without having to contend with smelly environmentalists and minority-interest bandits.

Just before he started his speech, Clouston made an offhanded remark about his reputation for soft-spoken oratory; a huge relief, given he isn’t an exciting speaker. That’s not a bad thing, by the way. On the contrary, it shows Clouston is self-aware which is a good thing… a very good thing. The last time a quiet man decided to “turn up the volume” everyone wanted him to shut up.

For clarity, there is a difference between an exciting speaker and an engaging speaker. The former concerns form whilst the latter concerns substance, and there was plenty of substance to his speech, both in terms of delivery and content. Clouston knows he’s a natural priest, and there’s nothing more off-putting than a priest who tries to be exciting. As such, Clouston stuck to what he’s good at: giving clear, methodical, and authoritative sermons, dictating the creed to the congregation, plucking quotes from the writers and leaders of bygone ages like prophets from the Old Testament; an Apollonian counterbalance to the Dionysian rabble-rousing of the chain-smoking, ale-chugging Nigel Farage.

And what was this creed, exactly? What was he cooking? “Vote positively” (if you believe in something, vote for it; that is, participate in democracy), “don’t vote Tory” (self-explanatory, in more ways than one), “don’t vote for anyone who doesn’t know what a woman is” (it’s certainly preferable to the alternative), “elect national leaders not charity workers” (Leeds is more important than Lagos), “don’t divide us” (stop being anti-white and turning Britain into a low-trust hellhole), “support conviction politicians” (hear, hear), “trade deficits matter” (HEAR, HEAR), and consider standing for election (we’ll get to this).

Of course, Clouston wasn’t the only speaker. Rod Liddle gave an unreservedly pro-Israel speech, whilst Laura Dodsworth outlined the dangers of social engineering. Graham Linehan was brought out for his regularly scheduled post-cancellation rehab session. Hugo de Burgh, who really should get into voice acting, gave a good speech on the long-term consequences of short-termist politics. In other words, there was something for everyone, it wasn’t half-a-day of “The Left Have Gone Quackers!” and such.

In-between speeches, it was abruptly announced that the SDP had received £1,000,000 from an anonymous donor. I could be wrong, but I’m guessing it was Paul Marshall. My evidence? First: I suspect the SDP is too dirigiste for the likes of Jeremy Hosking, even if he enjoys the so-called culture war aspects of contemporary politics. Compare this to someone like Marshall, who stood for parliament in Fulham in 1987 as an SDP-Liberal Alliance candidate and has provided support to organisations like UnHerd and the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship.

Second: Marshall’s son was on one of the panels. Winston’s contributions largely revolved around wanting to do stuff, rather than talking about doing stuff. Too right! Pontification only get us so far. Eventually, reality itself must be confronted as it is. Best not to waste your courage on fixing problems made in your own head, so to speak.

Still, discussions, forums, debates, etc. all have their place, and were present at the conference in addition to stand-alone speeches. Ross Baglin’s comments on the civil service were particularly welcome, as were his caveats to proposed fix-all technical solutions. As I have stressed to people many times, the political aspect of politics cannot be denied; the sooner we normalise viewing the civil service as a political problem, rather than some technical banality to be tolerated as part of British civic life, the better.

Of course, as Baglin also pointed out, this partially relies on conservatives developing a politicised frame-of-mind, overcoming their instinctual tendency to pursue an undisturbed life. Indeed, this has been a challenge in the past and remains a challenge now, but it’s evident that right-wing ideology, having been pushed to the periphery of public acceptance, has also attracted a large contingent of anti-establishment dissidents. Instinctually open-to-experience and somewhat contrarian, most have no interest in leading a depoliticised existence. Any party prepared to meet them half-way is sure to benefit.

However, despite the varying merits of the aforementioned, one could sense Matt Goodwin’s speech was the most anticipated, actualising in the most explicit form of praise one can receive on such occasions: a standing ovation. Concluding the SDP’s diagnosis of contemporary British politics was correct, and the consensus of the British public could be found in the party’s manifesto, Goodwin reassured members the only thing between their policies and a political breakthrough was a matter of publicity.

Goodwin covered the bases you’d expect him to cover. Left-on-economy good, right-on-culture good, CRT is divisive, Gary Lineker is a libtard (please keep in mind, dear reader, that I am paraphrasing quite a bit). Goodwin’s insistence on using the term “political correctness” instead of “woke” – apparently, 95% of British people understand what the former means, compared to roughly 50% for latter – was a pleasant surprise, as was his call for total war against Britain’s public institutions and political duopoly.

I shan’t hash out all of my contentions with everything that was said at the conference as they’re mostly theoretical points – that is, not specific to the SDP or even party politics in general – and deserve their own piece, if anything at all. Nor shall I conclude with my thoughts on what the SDP should do going forward. Like a corporate multinational stooge, I have outsourced such menial, unpaid labour to a young SDP activist, whose perspective is surely more valuable than anything I can provide here.

Instead, I shall conclude with this: the last of Clouston’s eight points won’t be for everyone. For many, building a house and/or writing a book is obviously preferable to running for Parliament. However, if there is an SDP candidate standing in your area, and your MP isn’t Sir John Hayes or someone of reliable calibre, it wouldn’t hurt to support them (assuming you’re not planning to stay at home on election day).

Putting aside the hang-ups one might have with the party’s chosen aesthetics, rhetoric and sloganeering, the SDP platform isn’t half-bad: protecting civil liberties, civil service reform, bringing now-foreign-owned industries and assets back under national control, and a generational pause on immigration is preferable to the prevailing consensus of mass servitude, debt, and immigration. One activist described the party platform as “Singapore mixed with Blue Labour.” Indeed, it’s unconventional; like ordering a bowl of rice to go with your lamb and mutton. An acquired taste, for sure. Possibly in need of some refinement, at least according to some. Nevertheless, there are objectively worse options on the menu. Zimbabwe mixed with Judith Butler, for example. Human flesh served with… human flesh.

This isn’t so much an endorsement as it is a request to keep an open mind. As Barry Goldwater once said: “Extremism in the defence of liberty is no vice and moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Similarly, conventionality at a time when national self-harm is standard procedure isn’t patriotic. When faced with such dire circumstances, a good dose of unconventionality may very well be in order, especially at the ballot box.

Post Views: 1,233 -

Britain Is No Longer a Land of Opportunity

A recent viral tweet showed two doctors leaving a hospital. They’ve surrendered their licenses to practice medicine in Britain and are instead heading off to work in Australia. It’s not unusual- the majority of foreign doctors in Australia are Brits. The problem lies in the fact that young, educated doctors do not see themselves thriving in Britain. Our pay and conditions are not good enough for them.

Are you annoyed at them for being educated through taxpayer funding before going abroad? Many are. Are you understanding as to why? So are others.

Whilst this particular tale does come down to problems with the NHS, it’s also an example of what is wrong with Britain at the moment. People, especially younger ones, haven’t got the opportunities that they should have. There is no aspiration. There is a lot to reach for and not a lot to grab.

What has happened?

Wages and Salaries and Income, Oh My!

A recent investigation by a think tank has revealed that 15 years of economic stagnation has seen Brits losing £11K a year in wages. Let’s put this into perspective. Poland and Eastern Europe are seeing a rise in GDP- Poland is projected to be richer than us in 12 years should our economic growth remain the same. The lowest earners in Britain have a 20% weaker standard of living than Slovenians in the same situation.

That’s a lot of numbers to say that wages and salaries aren’t that great.

By historical standards, the tax burden in the U.K. is very high. COVID saw the government pumping money into furlough schemes and healthcare. As the population ages, there is a further need for health and social care support. This results in taxes eating into a larger amount of our income. In fact, more adults than ever are paying 40% or above in taxation. It’s a significant number. One might argue that this does generally only apply to the rich and thus 40% is not a high amount for them, but is that a fair number?

With inflation increasing costs and house prices rising (more on that later), a decent standard of living is beyond the reach of many. This is certainly true for young people. With wages and salaries falling in real time, we do not have the same opportunities as our parents and grandparents. Families used to be able to live comfortably on one wage, something that is near impossible. Our taxes are going on healthcare for an aging population.

Do we want old people to die? Of course not. We just do not have the benefits that they did. Our income is going towards their comfort. Pensioners have higher incomes than working age people.

Compared to the United States, Brits have lower wages. One can argue that it is down to several things- more paid holidays and taxpayer funded healthcare. That is true, and many Brits will proudly compare the NHS to the American healthcare system. That is fine, but when the NHS is in constant crisis, we don’t seem to be getting our money’s worth. The average American salary is 12K higher than the average Brit’s. The typical US household is 64% richer. Whilst places like New York and San Francisco have extortionate house prices, it’s generally cheaper across the US.

Which brings us onto housing.

A House is Not a Home

Houses are expensive- they are at about 8.8% higher than the average income. This is compared to 4% in the 1990s. That itself is an immediate roadblock to many. Considering how salaries have stagnated, as discussed in the previous section, it’s only obvious that homeowning is a dream as opposed to reality.

Rent is not exactly affordable either. In London, the average renter spends more than half of their income on rent. Stories of people queuing for days and landlords taking much higher offers are commonplace.

House building itself is not cheap- the price of bricks have absolutely rocketed over recent years. Factors include a shortage of housing stock and increased utilities. House building itself is also not easy.

NIMBYs have an aneurysm at the thought of an abandoned bingo hall being turned into housing. MPs in leafy suburbs push against any new developments, lest their wealthy parishioners vote for somebody else. Theresa Villiers, whose constituency sees homes average twice the U.K. mean price, led Tory MPs in an attempt to prevent house building targets.

We get the older folks telling us that we just need to work harder. It’s easy for them to say, considering a higher proportion of our income is needed to just get a damn deposit. If we’re paying more and more of our income on rent, how can we save?

Playing Mummy and Daddy

The ambition to become a parent is something many hold, but it is again an ambition that is unattainable. Well, the actual having the child part is easy, but it’s what comes after that makes it tough.

Firstly, we cannot get our own homes. Few want to raise their children in one bed flats with no gardens. To plan for a child is to likely plan a move.

Secondly, childcare is very expensive. Years and years ago, men went to work and women stayed home with the children as a rule. Of course, that did not apply to the working class, but it was a workable system. Nowadays, you both have to work. Few can survive on a single income from either parent. Grandparents are often working themselves or simply don’t/can’t provide babysitting duties. This leaves only one choice- professional childcare. The average cost of childcare during the summer holidays is £943. Some parents pay more than half of their wages on childcare.

Thirdly, as has been said, everything is more expensive these days. One only has to look at something basic like school uniforms- some spend over £300 per child. It’s not cheap to look after adults, let alone children.

The Golden Years

The focus of this piece is generally on young and working age people, but the cost of social care is pretty bad. With the costs of home and residential health care increasing constantly, it means that many will lose their hard earned savings. Houses must be sold and pensions given up. It is unfair that we must work all of our lives but then leave nothing for our children if we wish. Whilst residential homes are alien concepts to many in cultures where they look after the elderly, many factors in the U.K. mean that it is more common.

On balance, pensioners are better off than the young, but what about those who need care? It may be bad now, but what about when we ourselves are old? We will likely still be working at 70 and having to pay more for our care.

The Party of Aspiration and 13 Years of Power

The Conservatives have always called themselves the party of aspiration. They’ve been in power for 13 years, eight of which were without a coalition party. The Tories won a stunning majority in 2019 under Boris Johnson. They’ve had the opportunity to do something about this but haven’t. It’s amazing that they wonder why young people don’t vote for them anymore.

Let’s not pretend Labour and the Lib Dems are any better either. The Lib Dems won the historical Tory seat of Chesham and Amersham partially by appealing to those worried about new housing. Labour’s plans aren’t particularly inspiring.

We cannot dream in Britain anymore. The land of hard work and fair reward is no more. We must simply sit by as our wages stagnate, houses get too expensive and the opportunity for family passes us by. Our doctors head to Australia for better pay and better conditions. Countries that would see immigrants come to us for a better life are seeing their own economies grow.

People shouldn’t be living with roommates in their 30s when what they want is a family. We deserve to work hard to secure a good future. We don’t deserve for our income to go on poor services and for our savings to go on residential care.

The Tories have had thirteen years to sort it out. Labour and the Lib Dems have had chances to put their plans across. Our politicians care more about talking points and pretty photo ops than improving our lives.

Let us have ambition. Let us seek opportunities. Let Britain be a land of opportunity once again.

Post Views: 1,143