This lively volume follows the development of right-wing thought in Britain between the beginning of the premiership of Labour’s Keir Starmer and the end of the presidency of Mark Hall of the United Party.

Richard Cruston, Professor of Political Theory at Trinity College, Cambridge, is a learned scholar who has written biographies of Edmund Burke, Roger Scruton and Jacob Rees Mogg. His deep knowledge of ideas and personalities were clearly essential in developing this book.

His story begins with the astonishing electoral failure of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in 2024 — ending almost fourteen years of more or less unrivalled Conservative success. In exile, the Conservatives found themselves fragmented, both politically, with the Johnson loyalists in a fiery campaign to make the unenthusiastic former Mayor of London and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Leader of the Conservative Party, and ideologically, with “post-liberals”, “national conservatives” and “classical liberals” vying for influence.

If conservative ideas mattered at all, it was in their influence on the Labour government. Professor Cruston is an authority on the development of post-liberalism — a communitarian trend which earned support in the wake of the 2028 London riots — which spread from the capital across provincial England — as its emphasis on order and localism chimed with the state’s management of societal division. Cruston suggests that there might have been the faint whiff of opportunism in the combination of communitarian rhetoric and neo-authoritarian security measures — with more of an emphasis on “community hubs” and “peace enforcement” than on family and faith — but it was politically successful.

The 2030 blackouts were considered the beginning of the end for the Labour government. Prime Minister Meera Devi won the 2032 elections on a platform that some commentators called “neo-Thatcherite” — promising economic liberalisation, energy reform and closer links with what became known as “the younger powers”. Professor Cruston disapproves of what he describes “the fetishisation of the market” — though he doesn’t say where the power was meant to come from.

Devi’s government placed significant emphasis on character and individual responsibility. “Disciplining yourself to do what you know is right and important,” she was fond of saying, quoting Britain’s first female prime minister, “Is the high road to pride, self-esteem, and personal satisfaction.” Regrettably, her time in power was dogged by scandal, with ministers being accused of cocaine addiction, using prostitutes, doing cocaine with prostitutes and being addicted to doing cocaine off prostitutes.

Ashley Jones’ Labour premiership offered conservatives a chance to regroup. Had they forgotten the ends of politics as well as the means? Were they too focused on economics and not culture? Cruston is informative on the subject of the traditionalist “Lofftism” which flourished in the late 2030s, only being interrupted by the “Summer of Crises” which finally led to the United Party taking power in March 2039.

Conservative thought flourished in the early years of the 2040s, with generous funding being invested in private schools, universities, think tanks and private clubs. Here — if you were fortunate enough to be invited — you could hear about great right-wing minds from Hayek to Oakeshott, and from Kruger to Hannan. It was a time of intellectual combat but also intellectual collegiality. Millian liberals could debate Burkean conservative and yet remain friends. You could say anything, some intellectuals joked, as long as you didn’t influence policy.

With the unexpected departure of President Hall on the “New Horizons” flight the future of British conservatism looks mysterious. Professor Cruston counsels that we return to Burke — a voice that spoke in a time of similarly great upheaval. Perhaps we should heed his words.

You Might also like

-

Against the Rationalists

I had forgotten why I wrote ‘Against the Traditionalists’, and what it meant, so the following is an attempted self-interpretation; for that purpose, they are intended to be read together.

The Preface of Inquiry:

God hath broke a motley spear upon the lines of Rome,

When brothers Hermes masked afront Apollo’s golden throne.

The Aesthetics of Inquiry:

Metaphors we hold in mind, those scenes with their images and progressions, are of the fundamental sense that orders our perceptions and beliefs, and from which everything we create is sourced; for metaphors are dynamic and intuitive relations; and they emerge from the logic of the imagination—let us have faith that our logic is not cursed and disordered, in its severance from the Logos. The phenomenologists would be amply quoted here if they weren’t so mystical and confused—alas, one can never know which of the philosophers to settle with as they’re all so sensible, and they can never agree amongst themselves, forming warring schools that err to dogmatism since initiation—so it is to no surprise that ideologies are perused and possessed as garbs regalia, and for every man, their emperor’s new clothes.

If brevity is the soul of wit, then genius is the abbreviation of methodologies. Find the right method of inquiry, for the right moment: avoiding circumstantial particulars, preferring particular universals; even epistemic anarchist, Feyerabend, would prefer limited, periodical design to persistent, oceanic noise. One zetetic tool of threefold design, for your consideration, might be constituted thusly: axiomatic logistics—Parmenides’ Ladder, founded, stacked and climbed, with repeated steps that hold all the way; forensic tactics—Poe’s Purloined Letter, ontologically abstracted over to compare more general criteria; panoramic strategy—puzzling walnuts submerged and dissolved in Grothendieck’s Rising Sea, objects awash with the accumulated molecules of a general abstract theory. Yet, do not only stick your eye to tools, lest you become all technique, for art, in Borges, is but algebra, without its fire; and let not poor constructs be ready at hand, for the coming forth a temple-work, in Heidegger, sets up the world, while material perishes to equipment, and equipment to its singular use.

Letters of Fire and Sword:

A gallery of all sorts of shapes, and symbolic movements, exist naturally in cognition and language, and such a gallery has it’s typical forms—the line and circle, for example, are included in every shape-enthusiast’s favourites—though Frye identifies more complex images on offer, such as mountains, gardens, furnaces, and caves—and, most unforgettably, the crucifix of Jesus Christ. I’d write of the unique flavours of languages, such as their tendency to particular genres, to Sapir and Whorf’s pleasure, yet by method I must complete my first definition—now from shapes, their movement. The cinematographic plot of pleasing images adds another dimension to their enjoyment—moving metaphors, narrative poetry, being the most poetic; their popular display is sadly limited to mainly the thesislike development of a single heroic journey, less so the ambitious spiral scendancy, or, in the tendency of yours truly and Matt Groening, disjointed and ethereally timestuck episodes in a plain, imaginary void. The most beautiful scenes, often excluded, are a birth and rejoice, the catharsis of recognition, and the befalling ultimate tragedy and its revelation to universal comedy—these stories hold an aesthetic appeal for all audiences, and that’s a golden ticket for us storytellers.

If memory is the treasurehouse of the mind, then good literature is food for the soul. In the name of orthomolecular medicine, with the hopes that exercise and sleep are already accounted for, let your pantry be amply stocked and restocked with the usual bread and milk, with confectionary that’s disappeared afore next day, and with canned foods that seem forever to have existed—as for raw honey, a rarer purchase, when stored right it lasts a lifetime, and eversweet. I’m no stranger to the warnings against polyunsaturated fats by fringe health gurus, but I think I’ll take my recommendations from the more erudite masters of such matters; and I’m no stranger to new and unusual flavours, provided they’re not eaten to excess. The canonical food pyramid of Western medicine, in its anatomical display of appropriate portions, developed from extensive study and historical data, places the hearty reliables en masse at its foundations, and the unhealthiest consumables at the tiniest peak, so that we might be fully nourished and completed, while spared of the damage wreaked on our bodily constitution by sly treats of excess fats, sugars, and salt. Be rid of these nasty invaders, I say, that’d inflame with all sorts of disease; be full of good food, I say, that’d sharpen the body’s workers to good form. Mark the appropriateness of time and place when eating to the same measure; a diet is incomplete without fasting—let your gut some space to rest and think. And note the insufficiency of paper and ink as foodstuffs, and the immorality of treating friends like fast food—the sensibility of a metaphor must be conducive to The Good as well as The Beautiful, if it is to be akin to The True. Aside, it is the most miserable tragedy that, for all the meaty mindpower of medieval transcendental philosophy, they did not explore The Funny—for the Gospels end in good news, as does good comedy.

Bottom’s Dream:

Shakespeare—The Bard of whom, I confess, all I write is imitation of, for the simple fact I write in English—deserving, him not I, of all the haughtiest epithets and sobriquets that’d fall short of godhood, writes so beautifully of dreams in Midsummer’s Night’s, and yet even he could not do them justice when speaking through his Bottom—ha ha ha, delightful. “I have had a dream, past the wit of man to say what dream it was: man is but an ass, if he go about to expound this dream. Methought I was—there is no man who can tell what. Methought I was, —and methought I had, —but man is but a patched fool, if he will offer to say what methought I had. The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report, what my dream was. I will get Peter Quince to write a ballad of this dream: it shall be called Bottom’s Dream, because it hath no bottom…”, Nick Bottom, from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. At the end of Act IV, Scene 1.

Intermission, The Royal Zoo:

A Prince and three Lords did walk in the garden, and they sauntered about for the day.

The soon-to-be-King became awfully bored and inquired what game they could play.

“Perhaps, Sire, it’d be best to prepare”, they said, “for life’s duties that approach”.

“It is proper to train for a life’s work”, said they, “lest that debts’ hunger encroach”.

“Consider the rats”, said the Money Lord, “how they scavenge and thrift for tomorrow”.

“For their wild life is grim, and tomorrow’s tomorrow, so take what you can, and borrow”.

“Consider the lions”, said the Warrior Lord, “how they prowl and sneak for a bite”.

“For the proud life is hearty, strong conquers weak, lamb shanks easiest sliced at night”.

“Wise, yet consider the spiders”, said the Scribe Lord, “for they outwit both lion and rat”.

“To scavenge is dirty and timely, and hunting so tiring, better cunning employed to entrap”.

The Prince, unsatisfied by his Lords, summoned a Squire to ask of him his opinion:

“Squire, what do you do, not yet enslaved by your profession, that maketh life fulfilling?”.

“I play with whom I play, and with whom I play are my neighbours, my friends”, said Squire.

For that, said The Prince, “I will live not like a beast”, “I will live like a man!”,

And three Lords became three furnaced in fire.

“Then I commended mirth, because a man hath no better thing under the sun, than to eat, and to drink, and to be merry: for that shall abide with him of his labour the days of his life, which God giveth him under the sun.”, Ecclesiastes 8:15, KJV. Amen.

The headstar by which we navigate, fellow Christians, is neither Athens nor Rome—it is Christ. “Be sure [Be careful; Watch; See] that no one ·leads you away [takes you captive; captivates you] with ·false [deceptive] and ·empty [worthless] teaching that is ·only human [according to human traditions], which comes from the ·ruling spirits [elemental spiritual forces (demons); or elementary teachings] of this world, and not from Christ.”, Colossians 2:8, EXB. Amen.

A Note on Opinion:

It is common sense, in our current times, that the most opinionated of us rule popular culture. Without a doubt, the casting, writing, directing, etc, of a major cinematic production project is decided in final cut by ‘the money’—so I speak not of the centrally-planned, market-compromised popular-media environment—but it is by the algorithm of the polemic dogmatist that metacultural opinions, of normative selection and ranking and structuring, are selected. One must be at the very least genius, or prideful, or insane, to have the character of spontaneously spouting opinions. It is an elusive, but firmly remembered anecdote that ordinary, healthy people are not politics-mad—ideologically lukewarm, at the very least. Consider the archetypical niche internet micro-celebrity: such posters are indifferent machines, accounts that express as autonomous idols, posting consistently the same branded factory gruel, and defended by their para-socialised followers over any faux pas, for providing the dry ground of profilicity when sailing the information sea. Idols’ dry land at sea, I say, are still but desert islands—houses built on sand. Now consider the archetypical subreddit: ignoring the top-ranking post of all time either satirising or politicising the subreddit, and the internal memes about happenings within the subreddit; even without the influence of marketing bots, the group produces opinions and norms over commercial products and expensive hobbies, and there is much shaming to new members who have not yet imitated and adopted group customs; essentially, they’re product-review-based fashion communities. Hence, the question follows: if knowledge is socially produced, then how can we distinguish between fashion and beauty—that is, in effect, the same as asking how, in trusting our gut, can we distinguish lust and love? How can we recognise a stranger? Concerning absolute knowledge, including matters of virtue and identity, truth is not pursued through passion’s inquiry, but divinely revealed. “Jesus said unto them, Verily, verily, I say unto you, Before Abraham was, I am.”, John 8:58, KJV. Amen.

A Note on Insanity:

It is common for romantic idealists to be as dogmatic as the harsh materialists they so criticise. All is matter! All is mind! One ought to read Kant methinks; recall Blake’s call to particularity: there needs be exceptions, clarifications, addendums, subclauses, minor provisions, explanatory notes, analytical commentary, critique, and reviews—orbiting companion to bold aphorism; Saturn’s ordered rings, to monocle Jupiter’s vortex eye, met in Neptune’s subtle glide. Otherwise, the frame is no other than that which is criticised: arch-dogmatism. If we’re to play, then let us play nicely; it is not for no reason that Plato so criticised the poets, for the plain assertions of verse do not explain themselves, and so are contrarywise to the pursuit of wisdom in a simple and subjectivist pride—selfishly asserting its rules as self-evident. Yet, they might be wedded, for truly there is no poetic profession without argumentative critics—no dialectic without dialogue. And so, if I must think well, and to accept those necessities, then questions of agency be most exhaustive nuts to crack. If all is matter, then all is circumstantial—If all is mind, then all is your fault; if all is reason, we’re bound by Urizen’s bronze—if all is passion, we’re windswept to fancy. Unanswered still, is the question of insanity. And even without insanity, what is right and what is wrong so eludes our wordy description. “So whoever knows the right thing to do and fails to do it, for him it is sin.”, James 4:17, KJV. Amen.

Endless curiosities might unravel onwards, so shortly I shall suggest a linguistic idealist metacritique of mine own, that: to make philosophy idealistic, or to naturalise the same, are but one common movement, merging disparate literatures representing minds, of the approach to total coherence of the human imagination; such that might mirror the modal actualism of Hegel, a novelist who was in following, and ahead of, the boundless footsteps of short story writer, Leibniz. To answer it most simply: for four Gospels, we have fourfold vision, so if one vision is insufficient, then two perspectives are too—all-binary contradiction is the workings of Hell, but paradox and aporia, is, as exposited by Nicholas Rescher and Brayton Polka, the truth of reality. This way we might properly weigh both agency and insanity, by taking the higher ground of knowledge and learning. Recall Jesus’ perfect meeting of the adulterer—when he saw the subject and not the sin.

A Note on Disability:

There is potential for profound beauty in the inexpressible imagination, such that would make language but ugly nuts and bolts, if it didn’t also follow that we cannot absolutely explicate language either. Then, it seems even if our words do not create the world, but are representations, we can still know and appreciate facets of reality without their full expression—our words construct models, or carve at the joints of the world, but the good and beautiful expression is true proof of God; to recognise truth is intuitive, perhaps being that mental faculty which is measure sensibility. Hence, let us first pray that we are all forgiven for our sins, ignorant and willing, and second, that the mentally disabled, and lost lambs without dreams, can know Him too. Amen.

Post Views: 1,036 -

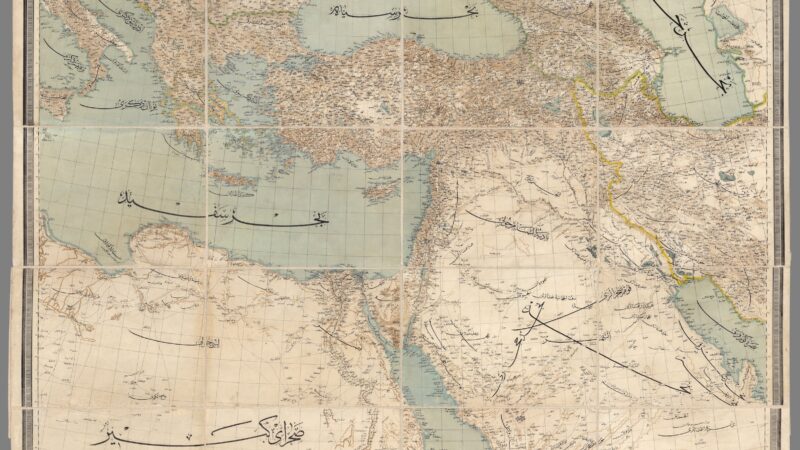

The ‘Lines in the Sand’ Myth

The idea that European colonialism is the original cause of modern day political strife in the Middle East is a popular one both in academia and amongst large sections of the general public. It originated in political science literature in the 20th century but has been ham-fistedly revived in the 21st, particularly in the context of the Syrian Civil War.

The narrative goes that the region was greedily carved up by the British and French empires following their victory over the Ottomans in the Great War. Bumbling colonial administrators drew straight lines in the sand, bounding territory arbitrarily and mixing peoples with arrogant disregard for differences in culture, ethnicity or religion. The resultant states were thus internally divided, unstable and weak – and it’s our fault. While it might be funny to point out the worrying implications this might have for our own enthusiastically multi-cultural society, it’s easier and more effective just to point out that it’s false. In actual fact, the states created by the much-maligned Sykes-Picot agreement have their roots in the pre-war Middle East and were starting to take shape in the 19th century as a result of various Ottoman attempts at reform.

Ironically, most who blame colonialism and Sykes-Picot for strife in the modern Middle East are doing a ‘Eurocentrism’ (a term you’ve certainly heard if you’ve spent any time as a humanities student) by exaggerating the impact of European empires and downplaying the importance of the Ottoman Empire. It’s high time we decolonise our thinking and give deserved credit to the Ottoman Empire for sowing the seeds of destruction in the fields of Iraq and Syria.

Syria, or ‘Suriyya’ as it was then known, began to take shape as a political entity in the mid-19th century as a result of a series of infrastructure improvements that connected previously isolated highlands with the cities of the coastal area of Bilad al-Sham. The creation of the Beirut-Damascus highway by French entrepreneurs encouraged more European commercial activity in the region as Beirut became the link between a significant portion of the Ottoman empire and the industrial economies of Europe.

Prior to the creation of the highway, Syria’s dismal transportation infrastructure left the region fractured and much of its population isolated. Improvements connected people in isolated hinterlands to participate in the economies of the wider region, uniting diverse and divided peoples together and forging a regional (and later national) identity. This infrastructural development occurred parallel with the aforementioned intellectual development that created ‘Suriyya’ out of Bilad al-Sham and the surrounding area. In 1863 local administrative boundaries were redrawn and the province of Suriyya was made concrete for the first time.

Syria was not the only state with a formation that predates Sykes-Picot, either – Iraq developed similarly. Iraq in the early 19th century was even more of an infrastructural backwater than rural Syria. While the main artery of 19th century Syria was the road, in Iraq it was the canal. Steamships in the 1860s cut the journey time from Baghdad to Basra down to just ten days while before it had been four weeks. Just as the Beirut-Damascus highway connected Syria to the world and to European trade, canal routes through the Persian gulf were what connected Iraq.

Although Iraq was never unified as a single province under the Ottomans like Syria was, the group of territories it comprised were referred to commonly by Ottoman administrators as ‘Iraq’ from as early as the sixteenth century. The skeleton of an Iraqi state can be seen also in the actions of the army, which was often organised in Iraq as a separate unit of its own with a headquarters in Baghdad, irrespective of the boundaries of local government. Despite the existence of religious and ethnic differences in both of these nascent states, importantly, all Iraqis rose up against British rule in 1920 as Iraqis and all Syrians rose against the French in 1925 as Syrians.

So we’ve established that Syria and Iraq, at least, were not entities made up by imperialists for their own convenience but rather nations that had formed organically out of a period of upheaval and transformation. However, the 19th century created a lot of disunity as well as unity in the region.

From the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, poor infrastructure, low literacy rates and the relative remoteness of much of the Middle East meant that religious doctrine could not exert as commanding an influence as it could elsewhere and there was significant blurring and admixture of local communities. In the most isolated areas, lines between Christian and Muslim, and Shia and Sunni communities were blurred such that it was difficult to distinguish between them.

However, Ottoman constitutional reforms – known collectively as the ‘Tanzimat’ (‘reorganisation’) – crystallised this distinction by granting non-Muslims full legal equality with Muslims. The removal of the privileged position of Muslims in the Ottoman empire came at a crucial time of increasing European commercial dominance and penetration. Some Muslim textile workers thus began to resent Christian counterparts who, they felt, were gaining the upper hand on them thanks to connections with Europe and the preference of European merchants to do business with Christians. Local elite, who sought to preserve their power by opposing the Tanzimat were then able to use this to their advantage by framing their opposition to reforms in ethnoreligious terms, fanning the flames of sectarianism. The starkest example of this phenomenon reaching boiling point is the 1860 Damascus riots in which between 5,500 and 8,000 Christians were killed.

In this we can see clearly patterns of sectarianism and a political landscape that is very similar to what we have today. The only thing preventing large-scale violence from occurring up until the 20th century was the existence of the Ottoman state and the authority of the Sultan. However, the Ottoman Empire had territorially been in slow retreat since 1683 and modernisation – attempts to create a Western-style Weberian state – had repeatedly failed or achieved only partial success. The truth is that the importance of the Sykes-Picot agreement and the post-WW1 colonial settlement in the Middle East is massively overstated in comparison to the events of the mid-to-late 19th century, which are massively understated.

The problem isn’t so much that a common misconception exists – history is full of them and this is by no means one of the most egregious – it’s that this falsehood is used in bad faith as a political weapon. It’s a narrative that fits nicely into a far-Left view of the world wherein the shadow of colonialism still lies over the whole world and is responsible for all evil and conflict. It is used to bash British people over the head with guilt so they take responsibility for all that goes wrong in the Middle East, particularly with regard to contentious topics such as asylum seekers, foreign aid and military intervention. ‘It’s our fault, you know,’ they say. It’s pernicious and ultimately ahistorical.

Post Views: 1,306 -

An Interview with Fen de Villiers (Magazine Excerpt)

Sam: A common criticism I hear from people on our side of the ‘cultural divide’, regarding Vorticists and Futurists, is that the avant-garde, as a concept, is antiquated. Do you think that’s true, or do you think people are being a bit too pessimistic about its potential?

Fen: Being pessimistic and cynical is something inherent to people who are more on the conservative spectrum, but I think that one must look back to go forward; you can clasp at the fire and the energy of a certain group or a certain movement, and then you can run forward with that. I don’t think it’s a case of saying, you look back at them and stay there.

I think that it’s going to take time, movements, and art styles to take a while to mature and find a new way. I don’t at all believe that we simply just have to take on what they do and just reside there.

Sam: In other words: “it’s not worship of the ashes, it’s the preservation of the fire.”Fen: Yes, absolutely. I think what’s important is that if you are going to throw this forward – I mean, the futurists were, for example, very excited by the motorcar and the aeroplane and flight, because that was the period that they were in.

I don’t think we need to be excited by the aeroplane in the material sense. However, I think we can be excited about something. That visionary and Faustian spirit is deeply ingrained within our European psyche. I think we get excited about going on and going forward. I don’t think it’s a case of simply just regurgitating the platitudes or what they were doing. It’s about finding a place for that energy now.

It’s really about energy and celebrating force over death and decay; the latter of these is what the current regime works on. It’s the cult of the victim. This is not glorious stuff. This is not about going upwards towards something higher: this is about keeping you on the lowest level. For me, that is not how life is, that’s not how nature is: it is a lie. It’s not a culture that has any sort of fire in the belly. It doesn’t make you want to live.

This is an excerpt from “Blast!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

Photo Credit: Fen de Villiers

Post Views: 1,081