My Vitalism (Magazine Excerpt)

In a world that is innately tragic, how does one remain cheerfully vital? There seems no end to the forces that wish to crush one’s joie de vivre. Whether it’s the deadening omnipotence of the modern technocratic mode of organisation, the overbearing coddling of our moralistic culture, or just the old-fashioned primordial fate of the great tragedians and philosophers, we cannot escape an assault of forces intent of making us submit to despair.

The world often feels like a great slimy toad, sitting on our chests and allowing its toxic ooze to envelope our nostrils and lungs until we choke. How many people give in to it I wonder? Millions? How many human beings surrender their souls to the devilish incubus that haunts them? This is the primary question of human existence and one that has become pertinent to the present moment in art. In a high culture full of worthless slush that threatens to drown us all in its mediocrity and potent purposelessness, the moment of choice is thrust upon us all as individuals: either we swim to sweet terra firma or fall beneath the murky surface.

Yet, as old King Canute once showed us, the tide is never-ending. In a deeper, spiritual sense the assault of despair will never end. We die and suffer. Our loved ones die and suffer. Religions are exhausted and nations fall to ruins. Given this, do we still have the strength to embrace life?

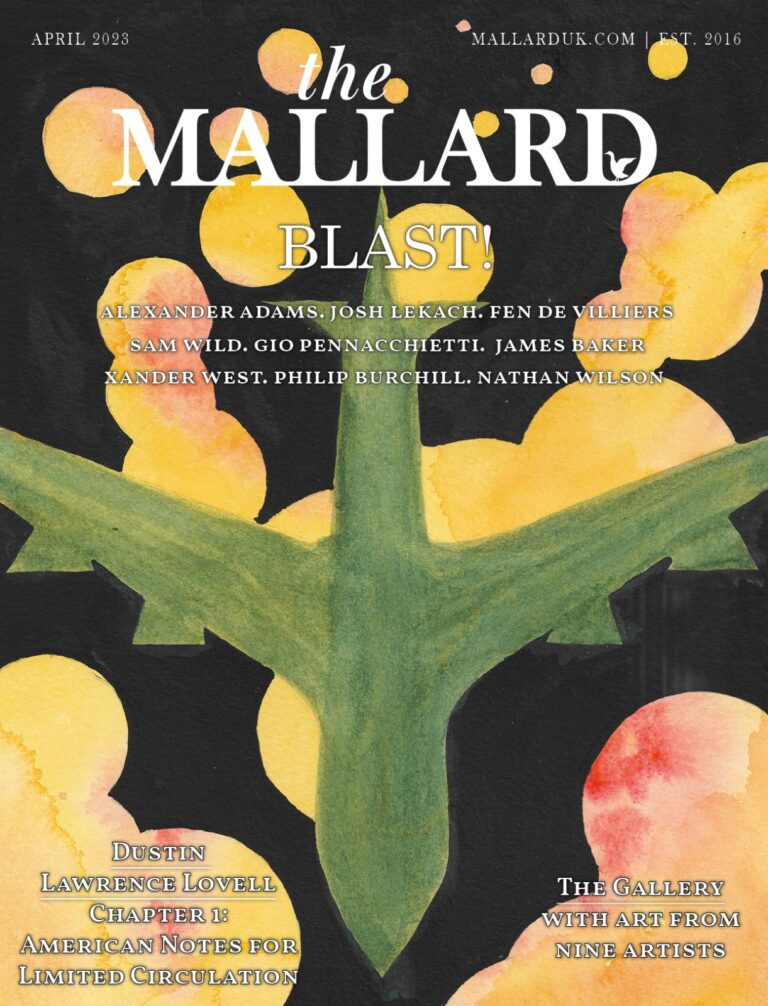

This is an excerpt from “Blast!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.