The longevity of her majesties reign lulled most of us into this false sense that she may well last forever. Alas; whilst she reigned over 15 prime ministers, 6 popes, and was just 2 years shy of breaking King Louise XIV’s record of the longest reigning monarch; she was ultimately mortal like the rest of us. Losing Elizabeth is like losing a relative in a way: she was effectively the spiritual grandmother of the nation. One does not have to have met her in person to realise the gravity of the situation and feel a sudden emptiness in ones soul. Regardless, there will be constant streaming in the news about the queen’s reign and whilst this is fully justified considering her extraordinary life; I think it’s equally important for us to look to the immediate future, regarding her heir and now king Charles III.

Like Moyes taking over from Ferguson, taking the reigns over such a distinguished and legendary predecessor in the form of Elizabeth II was always going to be a mammoth task for Charles III. Unlike Moyes though, I do believe Charles III will succeed in his role and will not only steady the ship and keep things stable for when William takes over but I also think he will be a decent king in his own right. There is the historical precedent to believe this will be the case as well if we look at the reign of King Edward VII.

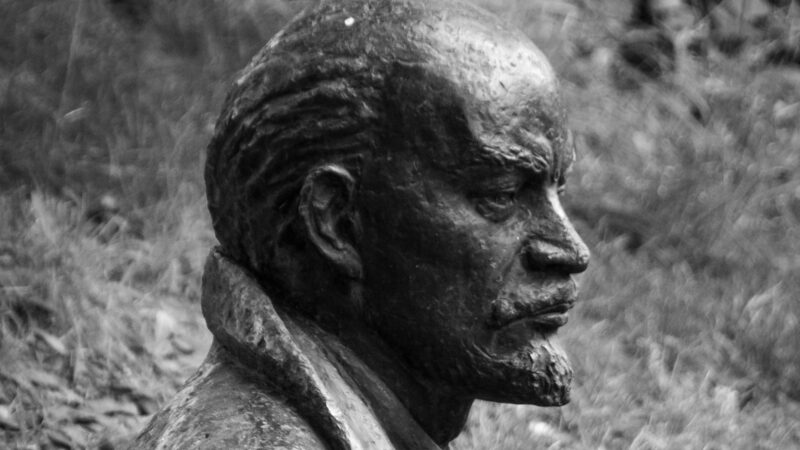

King Edward VII also had the unenviable task of taking over from a long reigning and highly respected monarch. That being his mother Queen Victoria. Not only this though but there were those who thought he’d be unsuited for the crown considering his extramarital affairs, serial womanising, as well as his other hedonistic vices which he indulged in (particularly his gambling habit). Yet, despite all of this, once he became king, he took on the role dutifully and he over time, garnered the respect and admiration of the public at large. He had in fairness a good foundation to begin with. He even became to be known as the ‘Uncle of Europe’, being seen as a breadth of fresh air after his mothers stuffy and stern rule. Charles III faces similar challenges. His past with Diana for instance has far from gone away and there are still rumblings from those who’d prefer the crown skip Charles III entirely and go to William instead. Ultimately though, I think Charles III reign will go much the same way as Edwards VII’s reign.

*Use any picture of King Edward VII here*

He will certainly not match his mothers longevity, but I imagine he’ll do much in his comparatively short reign. He may not be able to match her regality, but he’ll do his duty. He may not command the same love and affection, but with time, I imagine he’ll garner the publics respect.

Detractors of Charles III would also do well to remember that ultimately it’s not about the person but about the institution of monarchy that matters the most. This has been lost on people because of the wider publics affection for Elizabeth II. If you were to ask most people in the street, most would say that they’re much more pro Elizabeth II than they are pro monarchy. Elizabeth was certainly an exceptional public servant but again, it’s about the crown, not the induvial. It is the crown that forms as the cultural nexus point for our nation. It is the crown that serves as the constitutional foundation of this country. It is the crown that forms the last line of defence when everything goes south. Even if you (harshly) think Charles III will be a bad king, we must not be so short-sighted to put the institution of monarchy into question. Either because they think the institution should die with his mother out of principle or because of their personal dislike of Charles III.

To be frank as well, I really fail to see how Charles III will serve as a catalyst for the undoing of the monarchy. The monarchy has survived the disastrous reign of King John, The Peasants Revolt, The War of the Roses, was abolished after the civil war but restored after the tyranny of Cromwell, The Glorious Revolution, anti-monarchical (more specifically anti Hanoverian/Georgian) intrigue from whiggish elements in the 18th century; the crown has survived it all. Those who fear Charles III will or want Charles III to fail would do good to remember their history.

The coming days and weeks will be beset by mourning for our late monarch and I hope that everyone – regardless of political affiliation – can at least raise a toast to her majesty at a minimum. But at least where the monarchy is concerned, we should be more optimistic in this country: we have precious little else to be optimistic about. The reign of Charles III will, I think, prove fruitful for the nation. Time will tell, this piece may come back to bite me at a later date, but I fairly confident that I will be proven correct in thinking that Charles will turn out fine.

The Queen is dead: long live the King!

Rest in Perfect Peace Your Majesty, your son has it from here.

You Might also like

-

What I’ve Learnt as a Revolutionary Communist

This article was originally published in November 2021.

I have a confession to make.

A few months ago I was made an official member of the Revolutionary Communist Group after being involved as a participating supporter for about a month and a half. The RCG are, in their own words, Marxist-Leninist, pro-Cuba, pro-Palestine, internationalist, anti-imperialist, anti-racist and anti-capitalist. They believe that capitalism is causing climate change, which they refer to as the ‘climate crisis’, and that socialism/communism is the only way to avert catastrophe.

They believe that the twin forces of imperialism and capitalism work today, and have been working for hundreds of years, to enrich the Western capitalist class by exploiting the labour of the proletariat and plundering the resources of the ‘Global South’. They publish a bi-monthly newspaper entitled ‘Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism!’ which acts as an ideological core around which centre most of the groups discussions.

After two months of twice-weekly zoom calls, leafleting in front of busy train stations and protesting in front of embassies, I was finally invited to become an official member. I rendezvous-ed with two comrades before being taken to a door which was hidden down a dark alleyway and protected by a large iron gate – certainly a fitting location for a revolutionary HQ. Inside was an office and a small library stocked with all manners of communist, socialist and anti-imperialist literature including everything from Chavs by Owen Jones to The Labour Party – A Party Fit For Imperialism by Robert Clough, the group’s leader.

I was presented with a copy of their constitution, a document about security and a third document about sexual harassment (the RCG has had issues with members’ behaviour in the past). It was here, discussing these documents for almost three hours, that I learnt most of what I know now about the RCG as an organisation and the ecosystem it inhabits.

The RCG is about 150-200 members strong with branches across the country – three in London, one in Liverpool, Manchester, Norwich, Glasgow and Edinburgh and possibly more. In terms of organisation and decision-making they use what they call ‘democratic centralism’ – a sprawling mess of committees made up of delegates that appoint other committees that all meet anywhere between once every two weeks and once every two years. They’re also remarkably well funded, despite the fact that their newspaper sells for just 50p. They employ staff full time and rent ‘offices’ up and down the country. They draw income from fundraising events, members dues, newspaper and book sales and donations (both large and small).

Officially, the RCG is against the sectarianism that famously ails the Left. However, one zoom call I was in was dedicated to lambasting the Socialist Workers Party who, I soon learnt, were dirty, menshevik, reactionary Trots. We referred to them as part of the ‘opportunist Left’ who routinely side with the imperialists.

The RCG doesn’t generally maintain good relations with many other major leftist groups. Central to RCG politics is the idea of a ‘labour [small L] aristocracy’ – a core of the working class who have managed to improve their material conditions just slightly and so work against the interests of the wider working class, suppressing real revolutionary activity in order to maintain their cushy positions. The RCG sees the Trade Union movement as the bastion of the labour aristocracy. They see the Labour party also as their greatest enemy – ‘the single greatest barrier to socialism in Britain’.

The RCG takes issue with the SWP specifically over their attitude to Cuba. They believe that most Trotskyists are too critical of socialist revolutions that have occurred in the past and so are not real communists – after all, no revolution will be perfect. The RCG’s issue with the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) is that they resent how the CPGB claims to be the main organisation for communism in this country and uses its coziness with the trade unions as a signifier of legitimacy. However, the RCG believes that this makes the CPGB not much more than an extension of the Labour party, which it despises.

The CPGB-ML (Communist Party of Great Britain – Marxist-Leninist), on the other hand, are much closer politically to the RCG. They also share the same view on the Labour party. However, the CPGB-ML has recently taken a loud anti-trans position and so the RCG wants nothing to do with them.

Socialist Appeal are a group that has organised with the RCG in London before but the two do not get along due to, once again, the former’s (until recent) support for the Labour party every election. The RCG also shares views with Extinction Rebellion but XR now no longer wants anything to do with the RCG because of the RCG’s insistence on selling its communist newspaper at every event its members attend. The RCG insisting on trying to recruit members at every event it attends, including events co-organised with other groups, is a major source of friction and one of the reasons nobody wants to organise with them. It’s also one of the reasons why the RCG has stopped organising with LAFA – the London AntiFascist Assembly.

LAFA, I was told, are a chaotic bunch. They staunchly oppose all forms of hierarchy and make decisions on a ‘horizontalist’ basis. In true anarchist fashion, there are no official leaders or ranks at all in LAFA and decisions are made sort of by whoever takes the initiative. Unfortunately this means that those who become unofficial leaders in the group are accountable to absolutely no-one because they are not technically responsible for anything, and naturally issues arise from this quasi-primitivist state of affairs. Ironically, this makes the London AntiFascist Assembly kind of based.

Interestingly, one organisation with which the RCG has never had any problems is Black Lives Matter. The RCG and Socialist Appeal were (apparently) the only two groups out on the streets in solidarity with BLM last summer – BLM even allowed RCG members to speak at their events. The RCG enjoyed quite a close and amicable relationship with BLM right up until BLM decided at the end of last summer to effectively cease all activity, with the reason given to the RCG being just that ‘the summer has ended’. Presumably, the bulk of BLM’s activist base either had to go back to school or just got bored.

Although the RCG strictly prohibits any illegal activity at any of its protests, one clause of the constitution is ‘a revolution clause’ requiring members to leave their jobs and move house at the discretion of the RCG. I was told this clause has never been invoked and isn’t expected to be invoked for decades at least but is there in case a genuine communist uprising were to take place somewhere in the country and RCG leadership decided that it needed members to move into the area to help. The RCG is intent on staying firmly on the right side of the law for the foreseeable future – supposedly until class consciousness is raised to such a level that the time for revolution arrives. Whether or not history will pan out the way they think it will, only time will tell.

Perhaps most curious was the group’s confused stance on lockdowns. They are fiercely pro-lockdown and pro-mask, but also highly critical of the government’s approach for reasons that are quite vague. Why a communist organisation would want to place unprecedented power in the hands of a government – a Tory government no less – that it thinks operates as the right arm of global capital is beyond me. When I brought this up, a lone voice of dissent in my branch, I was told I had made a ‘valid point’ and that the group needed to discuss the matter further, but that was it. The only explanation I could arrive at was that unfortunately the RCG, and I think the Left generally, are deep in denial about being anti-establishment.

The RCG’s modus operandi is the weekly stall: three or four communists will take a table and a megaphone to a busy location and try to hand out leaflets and sell copies of the FRFI newspaper. The idea was that people whose values loosely align with those of the groups could be contacted and organised by way of these stalls. The law of large numbers means that these stalls are curiously successful – one two-hour stall at the weekend can sell a dozen newspapers and enlist a handful of people to be contacted by the group at a later date. The process of collecting people and funnelling them down the contact-member pipeline is a slow one with a low success rate, but they’re relentless.

Interestingly though, I believe their decades-old activist tradition is actually one of their biggest weaknesses. Ironically, so-called progressives are stuck in the past. The RCG has a very minimal online footprint – it uses its profiles on twitter and Instagram only to post dates for upcoming events. The RCG have so much faith in their traditional method of raising ‘class consciousness’ (translation: spreading communism) that they’re losing the internet arms race and thus their grip on young people – their traditional base. The fact that the group has a large proportion of older members might have something to do with it.

However, Leftists are good at street activism – they’ve been doing it for decades. Leftist activist groups have ingrained in their traditions social technology – sets of practices, behaviours and attitudes – that have developed over time and that their opponents would do well to familiarise themselves with, like looking at the homework of a friend (or in this case, an adversary).

The RCG believes that it is one of very few, maybe even the only, Leftist group in Britain today committed to maintaining a substantial street presence. One of the conditions for membership, after all, is promising to attend at least one street protest a week. The RCG no doubt take their activism seriously, with a comrade even describing the group to me as being made up of ‘professional revolutionaries’. They believe that they are growing and will continue to grow in strength, propelled by financial and then ecological crises. They are very excited for the collapse of the Labour party, which they believe is all-but imminent, because they think it will cause swathes of the Left to lose faith in a parliamentary means of achieving socialism and take to the streets, where the RCG will be waiting for them.

My time as a revolutionary communist has been challenging but what I’ve learned is no doubt valuable. I strongly encourage others to do as I have, if only just for a few weeks or so. Join your local leftist organisation – pick a sect, any sect! Expand your knowledge, see a different perspective and gain skills you might not gain anywhere else. Speak to people with a completely different viewpoint from yours and learn how they think, you’ll be a slightly better and more knowledgeable person for it.

Quote: Leftists are good at street activism. They have ingrained in their traditions social technology that have developed over time and that their opponents should familiarise themselves with.

Post Views: 966 -

If There is Hope, It Lies in the NIMBYs

~ To my good friend Chris, who – despite the best available treatment – continues to suffer with YIMBY brainrot. ~

If there was hope, it must lie in the NIMBYs, because only there in those nonconforming disregarded boomers, ~22 per cent of the population of Britannia, could the force to destroy the regime ever be generated. The regime could not be overthrown from within a newbuild. It is them and them alone who are capable of preventing further mass migration into these isles. Collective animosity to the transformation of our country over the last seventy years can only be galvanised through the emergence of direct and inescapable negative externalities of the immigrant population being here.

The NIMBY’s dug-in heels expose the costs of the unnatural population boom that has been imposed on us, through hospital appointment delays, waiting lists, the lack of available school placements, etc. and through these problems the British are made incapable of following the path of least resistance and fleeing their local ship and scurrying to cheaper houses elsewhere. NIMBYism will push us all against the wall and ensure we confront the real and existential threat facing our people.

Let us suppose we disregard the NIMBYs, fall to the knees of our enemies, and beg them to build more houses regardless of the protestations of white Lib Dem voters: for whom would they really be for? Such housing would only be accessible to the middle class and subsidised immigrants.

Around 80% of the population increase since 2001 has been due to immigration. Many settlements across the country such as Sunderland have seen a population decrease since 2001, yet have had vast newbuild suburbs tacked on around the area, so it has to be stressed that these houses being built are not for those already here.

The goal of house building is instead an attempt to maintain a semblance of stability as our occupation government intends to push immigration each year into the millions. The price of housing can never be brought down under this arrangement. All we can currently control locally in our own communities is how much space is opened up for displacement populations to be moved in. For a country that has had a negative birth-rate for decades, you would think that there would be no seething cries for concreting over the remaining pleasant lands unless there were some unnatural force being pulled forth from abroad artificially ballooning the demand for housing.

Quell your trivial lamentations, for if we are unable to own homes and the rent becomes too high we can always live with our families and they (the potential repopulators) can continue living elsewhere. The gap between rental supply and demand is like a Thermopylaen dam, holding back the forces of change and securing what remains of the villages and towns that we grew up in.

It is worth looking at the impulse towards YIMBYism before continuing on with the defence of NIMBYism. YIMBYs are, basically, a self-interested cohort of deracinated individuals incapable of feeling any sincere communitarian connection to the country they purport to care about. No one who ascribes to YIMBYism in the present could ever truly be right wing, and they are certainly not nationalists by any real definition.

The motivation for YIMBYs is the desire for personal material gain irrespective of the consequences to the wider nation as a whole. You would have to be deeply, spiritually indolent to be aware of the racial dimension to the present struggle yet continue to spend your time focused on pushing for as many things to be constructed as possible (lest the Roman goddess Maia smite you down from her Olympian high-rise building).

This can all be contrasted with NIMBYs, where, on the surface it seems to be primarily a cause wrought from self-interest, yet there is an implicit racialism, or at least communal collectivism, that animates them into spending so much of their time trying to stop the construction of anything near their homes.

There is a subconscious understanding granted to NIMBYs, by their blood and bones, that any and all development is wedded to the immigration issue, even if they do not articulate their reasoning as such. Even if they are outwardly liberal and vote for the uniparty, in one garish form or another, they have still been compelled to try and halt the stampede of construction; compelled by grander tribal considerations beyond their conscious control and far beyond the petty desires of their local area.

NIMBYs, God bless them, sit atop the large ball and chain shackled to the YIMBY bug man that is desperately trying to claw the nation towards total multiracial capitalist dystopia, under the guise of it being ‘based’ someday.

The NIMBYs, by their actions, are making it as difficult as possible for those in power to bring about their desired thousand-year panopticonic hell of global technocratic control. They exclaim with righteous fury ‘the character of the area will change’ and, with this implicitly reactionary rallying cry, they proclaim a stand is being taken in defence of what our ancestors left for us; in defence of what is ours, in defence of what we must dutifully preserve for those that will come after us. If you oppose these sentiments and side with the YIMBY cause of pro-building you are anti-white.

Who else is deserving of praise when these issues are discussed in our circles but the late great Richard Beeching, without whose cuts to our rail infrastructure we would be deprived of rural Britain in its frozen primordial state. This is the power of Levelling Down, the inadvertent preservation of what really matters, of what we conjure in our mind’s eyes when we hear the word ‘England’.

What would the demography and texture of life of rural areas look like had those arterial transport lines not been severed by the British Railways Board at that moment in time? Those geniuses of bureaucracy looked only at immediate cost-saving measures yet ensured much of Britain would progress far slower than the urban warts in the fore, much like how Eastern Bloc states were shielded from decades of societal and cultural degeneration occurring in the west.

This has already played itself out before in our past. In Victorian Britain, Peterborough and Swindon were enlarged and urbanised due to their status as railway towns, and in contrast, towns such as Frome and Kendal remained intact due to being bypassed by the main lines. What could be argued to have been unfortunate then has been insulating for rural areas affected in the same way now.

It is far harder to displace local economies and people when there is simply no infrastructure to enable newcomers moving in, and those in power know this. Even in official government reports, our overlords lament how the rural areas of our country continue to be white spaces (in contrast to our grey polyglot citadels to nowhere), which has only been possible because of our inefficient and underdeveloped infrastructure.

Even setting aside the more esoteric takes on NIMBYism, NIMBYs have plenty of legitimate reasons to be opposed to construction in the areas they live in. Villages and towns throughout the country are under threat of being subsumed into a mass of soulless commuter zones around the nearest city. Everything is set to be absorbed into a blob of suburban prison cells without community or belonging, all to line the pockets of parasitic housing companies and give ascent to the ethnic machinations of our destructors.

People who live in these places know that expansion means that everything outside of their front door will look and feel more like London and they correctly reject it. People instinctively recoil at the efficiency with which 5G towers were pockmarked across our landscape during the Covid ‘Lockdowns’ and people are right to be repelled by all of the slick technological wonders of ‘smart homes’ sold to us by our masters. None of these things are congruent with how anyone deep-down wants Britain to be.

YIMBYism is deceptive in its overall presentation as being the sensible or reasonable option, in contrast to the supposed extreme positions of many NIMBYs (which is a self-own in its own right), but YIMBYs do not actually care about real development of this country. Most, if not all, of the real solutions that would give us good-quality, affordable housing would be contrary to a policy of deregulating the economy and doing whatever international finance asks of us to be done to our land and people.

Such solutions would likely be decried as socialism or communism and with it the YIMBY would expose himself as but a pawn of the oligarchs, no longer a Briton in character or spirit. These points though are a distraction away from what really matters and such policy debates can only be relevant in a post-regime world without the albatross of near-imminent demographic erasure around our neck. The elephant in the room is quickly forgotten about if you even momentarily entertain the notion of house prices mattering beyond any other silly partisan issue discussed in Parliament.

But it is not just housing that is in contention. All forms of expansion and growth are, in the long-term, detrimental to our people whilst we are occupied. Everything done freely in our liberal, capitalist country in the last 50 or so years has been to the detriment of the people our economy is meant to be built around. Every power plant built or maintained allows Amazon warehouses to keep their lights on. Every railway built or maintained ensures employers can reasonably expect you to submit to the Norman Tebbit mindset for how we are to live and work. Every new motorway has facilitated increased population mobility and with it the new motley generation of white collar serfs defend their creators, scuttling across Britain’s surface unable to understand why the older, whiter parts of the country might have deep-rooted connections to the places they live.

This new generation, marketed as the ‘Young Voters’ or ‘Young People’, do not really exist in the same way that Boomers and Gen Xers do. Trying to appeal to or identify with this spectral universal generation of youths is to view these issues through an inherently post-racial lens, and by extension, to misunderstand the driving motivations of NIMBYism. The older generations, which are the bulk of those that sympathise with NIMBYism, are the only ones that matter politically and economically and counter-signalling them is implicitly a form of anti-white hatred.

The temporarily-embarrassed plutocrats in our midst are becoming more and more apoplectic when confronted with the reality that the vast majority of the British people want nothing to do with Singapore-style excess capitalism, no matter how desperately they attempt to sell to them the potential material gains and goodies.

We should aspire to be more like Iran, a Tehran-on-Thames, a country that actively restrains the degree to which businesses can expand so that everything stays small and localised. People yearn for flourishing high streets and dignified work local to where they were born, something Iran has succeeded at maintaining with its constitution and system of dominant cooperatives and Bonyads. This is tangential to the NIMBY/YIMBY divide but integral for understanding what is going on.

The British people want the things that they care about protected and secured and valued above the interests of capital or the growth of the economy. Our people have simply had enough of growth, progress and rapid change that they did not vote for, and their views on construction and economics are shaped by that impetus. Brexit Bonyads are inevitable.

If anything is to be conceded to the YIMBYs, it is that their urge to make things more efficient is understandable (natural really for any European man) and a good impulse to have. However, this impulse is being exploited against us, a form of suicide via naivety, where we continue pursuing these instincts in spite of the fruits of said efficiency. My position on nuclear power plants would probably be different if we were the ones in power, or perhaps the small percent chance of something going wrong and having all of Britain’s wildlife poisoned would prevent me from ever endorsing them.

Let us suppose we put pressure on our current regime, a regime similar to the Soviet Union except without any of its upsides, to build a nuclear power plant: can we trust that the diversity hires, rotten civil service and corner-cutting private contractors will not bring about a disaster worse than what occurred at Chernobyl?

Point being, many things which are bad for us now are not bad for us in principle (and vice versa), something atom cultist YIMBYs are incapable of understanding. YIMBYs are equally incapable of understanding why one might be averse to scientific innovations that amount to playing God and making Faustian economic bargains. Money spent on scientific research is better spent on just paying people to leave.

There is an alternative lens to look at everything through though. For those that do not just want to talk all day about nuclear power plants with people that wear polyester suits, for those that have higher values beyond ‘Jee-Dee-Pee’, for those that are capable of having principles they would put before their immediate personal comfort, there is the true way forward.

It is our duty to be revolutionaries, in the vein of Hereward the Wake, villainous rebels resisting the occupation government perched above us. NIMBYism is a successful strategy for a time, this time, in which we have no realistic chance at having power. Frustrating outcomes and disrupting their long march onwards is all we have in our illusory democracy.

Inefficiency is a good thing. We must crave blackouts like houseplants crave sunlight. Our only hope for liberation and true prosperity lies with our regime being as broken as possible. Our people must be pulled from their comfortable position in the warm, crimson-coloured bathwater and alerted to the fragility of their collective mortality. The international clique and their caustic bulldozer of modern progress now have a sputtering engine; it is all grinding to a halt and there lies the hope for our future.

Do not fret! Do not return like a battered housewife to those that wish to destroy us the moment things become inconvenient. Imagine pre-1989 Poles wanting to hold the Soviet Presidium to account, putting pressure on the government to be more efficient, the same government that is occupying their people – that is how ridiculous YIMBYs look to authentic British nationalists and patriots.

Our whole lens must be different if we are to meet the almost-insurmountable forces that tower above us, wishing for our end. As the Book of Job attests, the righteous suffer so as to test their faith in God, to make them more like Him, and to bring Him glory. So too must we be prepared to tolerate personal discomfort if we are to survive as a people, and it is absolutely a question of survival.

Existential threats require recalcitrant attitudes and policy positions and being unable to own a house or having to pay higher rent is a small price to pay to escape the present railroad we have been stuck travelling along since 1948. We all have a collective skin in the game. If the actual issue is not solved (the solution being our regime destroyed and immigration ended) then Britain, as it has existed for more than a millennia, is permanently erased off the map.

The inability to ‘live it up’ as a young voter in the supposed Gerontocracy is not something deserving of any hand-wringing, much less wall-to-wall tweets discussing housing and pensions every day. Some things, most things, matter more than housing being unaffordable and energy bills being costly.

Until they become conscious they will never rebel and until they have rebelled they cannot become conscious. Every wrench in the system creates another ripple, another scenario where the masses have their eyes opened to what has happened to their country and what is intended to be done with it in the future.

What lies before us is a task seldom asked even of our ancestors, it is a task of securing our existence before the brink, of pulling everything out from the abyss before it is brought to a state of total oblivion. There are no mechanical little fixes to any of this, civilisation does not work like that and all of the Poundburys and HS2s in the world will not improve our lot in this current epoch. The finest of McTrad housing estates will never be more beautiful than God’s raw, untouched nature.

NIMBYs instinctively know they are in a death battle and understand what really matters in this world. YIMBYs, on the other hand, think this is all algebra that requires university-brained midwits to solve. Damn the YIMBYs. Go forth thy NIMBY warriors, heroes of the fields and hedgerows, paragons of Arthurian legend; lead Britain back to its pre-modern, Arcadian state!

To conclude, a simplistic allegory will be provided: we are farm animals, farm animals on a big gay tax farm. If more barns and cottages are built things will not improve for the animals. More generators will just allow the farmer to expand the slaughterhouse. The solution is not more generators or more buildings on the farm. The solution is to shoot the farmer.

Post Views: 1,331 -

On the majesty of Britain’s unwritten constitution

In light of Boris Johnson’s recent attempts to cling onto his own personal power, many within the media commentariat have proposed the idea of a written and entrenched constitution. Such a solution is historically ignorant: as will be developed in the succeeding paragraphs, the miracle of Britain’s constitution is that its conventions have weathered all storms and continue to stand strong today. Whether it be the unequivocal adherence to Erskine May or the continued existence of Habeas Corpus, Britain’s conventions are to be proud of and cherished. For utopians, too blindly obsessed with rationalism and rigorous state planning, Johnson’s escapades provide the perfect alibi for constitutional reform. But they are as wrong as they have always been, even in the interesting times in which we live.

Many of these misguided pundits have suggested that the answer to Britain’s political woes is that it should look to the various nations across Europe and the West that decided long ago to adopt a codified and entrenched constitution, but what does such a constitution actually look like? For one, all the key constitutional provisions would be drawn up in a single document which would then be protected by a court of law. This would inevitably go far further than the current Supreme Court which only considers the principles laid down in the Human Rights Act (1998) which are, of course, in line with the European Convention of Human Rights. All future laws would be required to stand in compatibility with this document. Any executive which desired the alteration of this document would be naturally required to achieve a super-majority within parliament.

For a considerable amount of time, such an idea has stood at the forefront of many constitutionalists’ minds. Given the fact that the British public tend to spend more time worrying about the accessibility of public services, rather than constitutional issues, the idea of a written constitution has not quite permeated through to the masses. Brexit for many may have been about the sovereignty of the United Kingdom but the constituent vote that tipped the scale in favour of withdrawing from the European Union saw the threat of mass migration on public services. Why is it that the growth of the Eurosceptic movement peaked only a few years following a financial crash? It is unwise to use worn out clichés, but Bill Clinton was correct in asserting that “It’s the economy, stupid.”

This, however, may not remain the case. Class dealignment and the absence of any real proletariat movement has shifted many people’s interests away from economic issues and towards constitutional and political issues instead. With the insistent obsession amongst media apparatchiks, the Prime Minister’s drawn out occupation of No.10 Downing Street has really lit a touch stone amongst the British public. Johnson has rightfully been described as someone who throws caution into the wind when bending the rules to further the interests of himself or, in some cases, the British public. To list a few of his more provocative actions over the last three years, he prorogued parliament, watered down the ministerial code and restricted certain forms of protest. The point of this article is not that his actions were wrong, but rather that they have inspired a rejuvenation amongst radicals to further pursue constitutional reform. It is perfectly reasonable to desire high levels of robust executive scrutiny and accountability but codifying the law is not the way that one should go doing about it.

Even in an age in which nation-states increasingly subscribe to the same hegemonic notion of what a liberal democracy should look like, Britain remains nearly alone in that the roots of certain constitutional elements can be found centuries ago. Exemplifying this perfectly is the fact that the bicameral nature of parliament grew eventually out of the 8th century practice of Witan-based council rule. Even if one takes a strictly anti-anachronistic view of history, the first official parliament was called in 1236, a few years subsequent to the signing of the Magna Carta. The unique majesty of Britain’s constitution is that its legitimacy is found in virtue of its longevity. Such a system, when working effectively, is both natural and superior to any other constitutional format. A system built upon the trust of politicians to uphold constitutional conventions is both perennially fragile yet also preferable to anything else.

Yet, such an argument for the maintenance of our constitution has to be framed with the recent Westminster scandals in mind. As is already becoming apparent, the ongoing Conservative Party leadership election will have a great focus upon propriety and ethics within politics. Candidates, whose prior lives fell short of the squeaky-clean standards expected of them, will be faced with a considerable uphill battle. Media pundits love to jump on the bandwagon of criticising Sir Keir Starmer for being too boring but the reality is that, after the last few years of political chaos, much of the British public will want a prime minister who is serious and trustworthy, even if that means being a bit on the dull side. Ordinary people do not want to go about their lives worrying about politicians; they have far bigger concerns. As a result, I suspect that the next few prime ministers will bend over backwards to ensure individual decency and political stability.

On a different point, it is worth refuting the conservative argument which can be made for a written and entrenched constitution. Such a constitution would prevent radicals from unwisely or unthinkingly bringing a sledgehammer to the political system. One has only to look at the toxic legacy of New Labour. Admittedly, even David Cameron, a Conservative prime minister, attempted to abolish the House of Lords with a simple majority within the House of the Commons. It is perfectly true to argue that the preservation of a particular constitutional setup would remain existent for a long time if codified and entrenched behind a naturally conservative law court. However, if moderation is a fundamental conservative principle, then to alter the constitution in such a dramatic and radical way, even in an old-fashioned or nostalgic manner, would be, by definition, an unconservative thing to do. Purely in a hypothetical conservative utopia, a written constitution would be naturally the constitution of choice. We don’t live in a utopia though; we live in reality.

In contrast to the unwritten and uncodified dignity of Britain’s ancient constitution, the American constitution is constantly the source of unnecessarily bitter political debate and congressional blockage. If one were to take the second amendment, the right to keep and bear arms, there is still a decades-old, unresolved debate around whether or not to alter it. Discussions around laws that may appear to violate such amendments centre around whether or not the law is constitutional, rather than whether the law would actually be effective in practice. Debating the constitutionality of federal states banning the right to an abortion is an entire debate in itself and not one that an Englishman should necessarily engage with, however the recent decision to overturn Roe vs Wade does raise an interesting point. Following British tradition, it is far better that law-based decisions are determined by elected politicians, not by unaccountable judges. This point was rightfully raised at the despatch box by Dominic Raab while deputising for Johnson. To be a 21st century conservative, one must commit to upholding the democratic will of the people. Despite the influence of pro-Atlanticist conservatives, it is wrong to look to the USA as a political model.

Despite the temptations of a written constitution, politicians and activists must remain ever vigilant in their defence of Britain’s unwritten constitution. In order for our political system to develop naturally, prominent conservatives must put aside any admiration they may have for the American system and stand strong against historically-ignorant reformers. Preserving the way in which things are done is one of the core building blocks of being a conservative. This principle cannot be undermined by constitutional reformers, even if they are paradoxically trying to prevent radical reform. The checks and balances within the British political system have survived far worse than Johnson.

Post Views: 743