latest

Open Borders Rely on Political Irrationality

All too often, open-border policy stems from the fact that politics is determined by a class of people with deep-seated illusions about the facts surrounding immigration. Sweden is an ideal example of this pattern. Of all the countries in Europe, Sweden is especially notorious for having welcomed large numbers of refugees it could not properly integrate. In 2015, notes columnist James Traub, the country absorbed 163,000 of them. It has not gone well. Skyrocketing crime rates, mass unemployment among immigrants, and heavy strain on the welfare state have made Swedes weary of incoming foreigners. As a result, writes Traub, even Sweden’s Social Democrats have embraced ‘harsh language’ which used to be monopolised by ‘far-right nativists.’

This year’s November issue of the academic journal Kyklos includes the article Misrepresentation and migration, which explores the causes of that initial Swedish openness to migrants. Authors Anders Kärnä and Patrik Öhberg note that the extreme permissiveness with which migrants were let into the country ran radically counter to the will of the Swedish electorate. Voters’ dissatisfaction brought a right-wing government to power in 2022 and fueled the rise of the hard-right Sweden Democrats. Backlash was so strong that in 2015 the country’s prime minister was forced to make a U-turn and advocate for tougher restrictions after pushing for open borders earlier that year.

So why did the political class initially defy popular opinion to welcome hundreds of thousands of foreigners? Kärnä and Öhberg argue that Swedish politicians held far different views on the subject than their constituents. Polling coducted over the years shows that in every major party other than the Sweden Democrats, politicians were significantly less likely than their constituents to favour accepting fewer refugees until 2018. The authors conclude that pushback from the voting public, including through the emergence of the Sweden Democrats as a political competitor, eventually drove elected officials in other parties to revise their positions. Nevertheless, politicians from two of the three left-wing parties continued to be somewhat more pro-refugee than their constituents in 2018, the last year for which numbers are provided.

Contrary to what one might assume, the disagreement between politicians and voters did not occur because the politicians were better informed than the common people. On the contrary, they were deeply mistaken about the effects of their policies. The authors cite survey data from 2015 and 2017, showing that most Swedish politicians thought the economic impact of accepting refugees was ‘positive in the long run.’ However, they demonstrate that this belief is contradicted by all available peer-reviewed journal articles and by all the expert analyses of the issue which have appeared in official reports by the Swedish government. The existing studies indicated, and still indicate, that refugees are harmful rather than beneficial to Swedish economic performance. In other words, the idea that refugees were good for the economy was a piety which the political class held against all evidence.

Sweden’s experience is not unique. The immigration debate in the United States has also been marked by false ideas which politicians continue to hold despite overwhelming evidence against them. As Steven Camarota of the Center for Immigration Studies has observed, the notion that immigration can remedy ‘the aging of American society’ continues to be unquestioningly advanced by advocates of open borders even though it is blatantly inconsistent with the facts. The increasing average age of immigrants, their decreasing fertility rates, and the sheer size of the influx which would be required to offset American demographic woes make such a project impracticable.

Kärnä and Öhberg’s paper considers the irrationality of unfettered immigration only from an economic standpoint, but it is harmful in other ways as well. In addition to economic consequences, accepting countless immigrants whose values are incompatible with those of the host society creates sociopolitical problems with no obvious solution.

One such issue is organised crime. The Financial Times reports that, relative to population size, Sweden suffers from the third-highest rate of gun deaths of any EU country. A major cause of this epidemic is ‘[w]ell-established criminal gangs’ which are ‘largely run by second-generation immigrants.’ Sweden’s prime minister has identified ‘irresponsible immigration policy and failed integration’ as the root of the epidemic. Meanwhile, as France 24 details, the Swedish government is currently considering options which would let it deport ‘asylum-seekers and immigrants for substance abuse, association with criminal groups or statements threatening Swedish values.’

The political repercussions of large-scale immigration are also severe, and the presence of people who do not share Western values presents a serious threat. For instance, Sweden’s left-wing parties have dithered in their condemnation of Hamas’s terrorist attack against Israel. ‘If you assume,’ explains journalist Richard Orange, ‘that the 200,000, or perhaps even as many as 250,000, Arabic speakers [in Sweden] are broadly pro-Palestinian, that’s an important voter base.’

Dominik Tarczyński, a Member of the European Parliament from Poland, eloquently addressed the sociopolitical implications of immigration in a September speech. He pointed out that despite receiving no large-scale immigration, Poland was prospering economically, and said the Polish people did not want more migrants. ‘You know why? Because there are zero terrorist attacks in Poland,’ he explained, citing EU statistics.

Europol’s data on terrorism do indeed bear out Tarczyński’s claim. The agency’s Terrorism Situation and Trend Report for 2023 provides a map of the EU showing how many terrorist attacks and ‘arrests on suspicion of terrorism’ each country experienced in 2022. Poland was among the handful of states where none of either occurred. France was arguably the country most affected, with six attacks and 109 arrests, though Italy suffered twelve attacks and carried out 45 arrests. Notably, jihadist terrorism prompted far more arrests than any other kind of terrorism from 2020 to 2022, although leftist and anarchist terrorism accounted for a few more attacks – 44 versus 30. Sweden experienced an attack during this period. Poland did not.

The migrants’ cultural background is the key issue, more so than immigration itself. On another occasion, Tarczyński told leftist televison host Cathy Newman: ‘We took over two million Ukrainians, who are working, who are peaceful in Poland. We will not receive even one Muslim.’ This, he emphasized, was the will of the Polish electorate. If Tarczyński is representative – and he is – then Poland’s immigration policy is based on a realistic understanding of the effects of mass migration as well as on respect for the will of the people. As Kärnä and Öhberg show, both of these considerations failed to inform Swedish immigration policy for most of the 2000s and 2010s, and it is dubious whether they have enough of an impact even today.

Tarczyński’s motto is ‘Be like Poland.’ Swedish politicians should take that advice to heart. To judge by experience, however, it will fall to Sweden’s voters to make them do so.

Is The Pope Catholic?

Growing up, there was a saying my friends and I were fond of. Whether we were loitering outside a shop or putting our feet on the furniture, if we were challenged on our behaviour, our go-to response would always be ‘it’s a free country’. It didn’t always fly, mind you, but the utterance was common when I was young.

For obvious reasons, you never hear that one anymore. True, the country wasn’t really free then either, but we were not so heavily regulated and wrapped in a straight jacket of stifling laws as we are now. We could employ a bit of denial back then. An impossible comfort today.

We aren’t free. We know it every time we see a prohibiting sign, or try to express an innocent opinion now condemned, or utter one of those forbidden truths in the office which might see us brought before HR. We know it when the Tories let in hundreds of thousands of foreigners after pledging to cut immigration. We know it when the bank accounts we never wanted are plundered to pay for migrant accommodation, wars we don’t understand, and aid to countries with space programs. We know it when we see Christians arrested for praying silently by abortion clinics, or when local governments allow one protest, but not another, during state enforced lockdowns. We aren’t free, and so the old adage had to be retired.

Another popular saying goes, ‘is the Pope Catholic?’, which is used whenever the answer to a question is an unequivocal ‘yes’. You might think that this one is safe, but with the latest news coming out of the Vatican it looks as though we might need to axe that one too, as it has been revealed that Pope Francis has said his priests can now bless same sex relationships. Not the individuals in that relationship, but the same sex couple itself.

Now, I’m not a homophobe (though I’ve been called one), and neither am I a Catholic, but when I heard this news I couldn’t help but wince. I’m not saying homosexuals don’t have their place in the world, they do, though I’m not entirely sure that place is in the Catholic Church. I mean, the Bible is pretty clear on homosexuality, and it doesn’t exactly give a glowing review of the ‘lifestyle’. Like it or not, that’s how it is, and no man is supposed to be able to change that within the Church. Yet the Pope has done just that, seemingly ignoring the very religion of which he is a fairly significant part.

Some less pessimistic souls might say that the Pope is trying to save the Church by moving with the times. If that is the case, he has failed. Cultures, religions, and nations cannot pursue policies of inclusion. They must, if they are to survive, remain exclusive, with a set of rules or criteria which must be met to be counted among their number. I mean, look at what happened to Britain after it pursued the American style of inclusion and decided that being British took nothing more than the right paperwork. It didn’t take long before we weren’t even sure what Britain was anymore. The same will happen to the Catholic Church.

For my part I am not willing to give the Pope the benefit of the doubt on this one. I do not presume him to be a stupid man and therefore must suppose that he knew by trying to move the Church with the times in this manner, he was in turn rendering the Church redundant. I say this because, if the church is simply to bend to modern sensibilities, against the word of God or not, I can see no point in its existence. What’s next, acceptance of abortion?

Perhaps you feel I’m being hysterical, but remember, when gay marriage was passed in this country, it was done under the unofficial but regularly touted slogan of ‘what two consenting adults do in the comfort of their own home should be no one’s business’. We accepted that, and now we have drag queens reading stories to children and surgically altered men with breasts stripping naked on live television. The decline moves fast, and it appears that the Pope has just opened the door to it in the Catholic Church.

If this is not rejected wholesale by those under the Pope, then it is only a matter of time before we see videos of transvestite priests baptising non-binary infants while the two ‘fathers’ watch proudly. And thus, the Catholic Church will be no more. Perhaps that’s the future you want, but somehow I don’t think it’s the future Catholics want.

What we are seeing is another column of the world we knew falling to globohomo, a force which seeks to drape the world in a pall of moral relativism, and which seeks to destroy all spirituality and replace it with consumerism and fabricated, shallow identity. I have my feelings about that, but I’m not offering them here. I’m simply making a prediction. What I will say is this – the next time you ask someone a question and they respond ‘is the Pope Catholic?’, take that as a ‘no’.

Lord Cameron and the ‘New Majority’

A soft “What the hell” was heard from a reporter as former Prime Minister David Cameron stepped out of the car outside 10 Downing Street on Monday. The significance of the moment was quickly deduced as earlier Suella Braverman was sacked as Home Secretary and former Foreign Secretary James Cleverly had already walked through Britain’s most famous door: Cleverly becomes Home Secretary and Cameron, returning from political oblivion, replaces him as Foreign Secretary.

The appointment of Cameron, who is not an MP in the House of Commons and had to be elevated to a peerage by King Charles III to take office, is not only something no one saw coming. It is also a manifestation that Sunak might lead the Conservatives back in a direction that does not resonate with the voters.

A Look at the Political Realignment

A political realignment has been evident in British politics for just as long as in US politics. And it was the Conservatives’ realigned political approach, which emerged with the Brexit vote in 2016, that gave them a large majority in the 2019 general election. The landslide victory of Boris Johnson and the Conservatives was ultimately deliverable thanks to a large number of traditional Labour voters who switched in the hope of getting Brexit done.

It showed that there was a large voter base that the Conservatives could not only win over, but also lead them to large majorities. I will call this voter base the ‘New Majority’. This ‘New Majority’ can be sketched as conservative to very conservative when it comes to social issues while supporting economic positions traditionally held by left to center-left parties.

In conservative circles, the realignment towards this ‘New Majority’ is frequently viewed critically, especially by people who were thought leaders in the years before 2016. Primarily because they do not see this new orientation as being conservative, but rather interpret classical liberalism as being conservatism to advocate liberal social policy and economic libertarianism. This interpretation of conservative politics, however, is not only not conservative, but also a formula for guaranteed electoral defeat.

The Case for Conservatism

That this ‘New Majority’ should be the Conservatives’ target voter base and can be turned into a lasting majority is shown in the recent report “The Case for Conservatism” by Gavin Rice and Nick Timothy at Onward. As they put it:

“There is significant political advantage to be gained in a political party moving towards the real centre-ground. A more culturally conservative policy platform would bring the Tory Party nearer to Conservative voters’ social values. Mirroring this, an economic policy platform emphasising greater fairness and security, rather than deregulation and individualism, would bring it closer to the economic values of both Conservative and Labour voters.”

The report shows that there is a major disconnect between Conservative voters’ attitudes to economic and social issues and what the Conservatives are doing in terms of policy. In order to deliver policy that serves the electoral base, the report establishes 12 new core principles that lead to a “form of conservatism that takes long-established insights and principles and applies them to very modern challenges and problems. It argues for a conservatism that is popular and democratic, seeking to serve the whole nation.”

This includes a desire for a more active state, moving away from the old Conservative emphasis on limiting the state as much as possible. Working towards a fairer social contract by doing more for workers and families rather than pursue tax cuts that only benefit the few – an approach that was the beginning of the end for Liz Truss. And for the preservation of the environment, including more action on climate change.

On Suella Braverman

So where does David Cameron fit into this vision? He doesn’t!

Lord Cameron represents the pre-realignment form of the Conservatives, a form that makes policy not for those who find their desires reflected in the Rice and Timothy report but for the liberal elite who have benefited from previous Conservative governments.

Not only that, this appointment must also be seen in the context of the sacking of Suella Braverman. Braverman is a prominent figure who covers many of the concerns of voters who put their faith in the Tories – often for the first time – in 2019. Furthermore, for many people who felt that Rishi Sunak’s policies did not sufficiently address the concerns of the ‘New Majority’, she seemed a possible successor.

She spoke out against mass legal and illegal immigration. The Rice-Timothy report states “Currently, 63% of voters say that inward economic migration is too high” and “Polling conducted for Onward shows that there is a migration-sceptic majority in 75% of parliamentary constituencies.”

She spoke out against multiculturalism. Rice and Timothy’s report cites a Demos study which found that “71% of British adults say they believe that immigration has made the communities where migrants have settled more divided, reaching 78% in high-migration areas.”

And she spoke in defence of national identity. The Rice-Timothy report states, “A 2021 poll found that 61% of voters said they were very or fairly patriotic, compared to just 32% who said they were not very or not at all”.

These three examples alone show that her views are in line with those of the British population and even more so with those of the Conservative voters of 2019, who form part of the ‘New Majority’.

The Meaning of David Cameron’s Appointment

Now Lord Cameron is given a place in the Cabinet, while Braverman is sent back to the backbenches. Although he has not directly replaced her, one has to imagine that the two personnel decisions are viewed hand in hand and show two very different pictures of Conservative politics.

The ‘new majority’ will certainly perceive this as a vindication of pre-2016 policies and refrain from voting Blue in the next general election. One can’t have a former Prime Minister in the Cabinet, especially in one of the Great Offices of State, without them shaping, at least in part, what voters expect from the Party would they vote for them. And in this case, they are likely to see a return of social and economic liberalism, which, as Rice and Timothy show, as a “political outlook represents just 5% of voters”.

Not only that, but the politicians in the Conservative Party who supported Cameron and often held up the Remain banner will feel validated by this and may feel the momentum in the party shifting back towards them. Now people such as former Deputy Prime Minister Lord Heseltine are saying that Rishi Sunak should even consider bringing someone like George Osborne back into the cabinet, or at least letting him work on the levelling-up agenda.

What does this appointment tell potential voters? As Matt Goodwin puts it, “It’s telling them the Tories would much rather return to the pre-Brexit liberal Cameroon era of 2010-2015 than reinvent and renew themselves around the post-Brexit realignment, that they are simply incapable of reinventing who they are.”

What is the Point of the Turner Prize?

Picture the scene. Strings of tattered bunting, the concrete shaft of a half-built pillar. At the centre of it all a pile of red and black folders, supplanted by a pair of flagpoles bearing faded Union Jacks. A length of striped tape lies beside them on the floor like the shed integument of a snake, and everywhere you look you see road barriers, twisted, contorted, lopsided. If it weren’t for the fact that the setting of the scene is Towner Eastbourne art gallery, you’d think a car had crashed through it. And you probably wouldn’t blame the driver.

This isn’t the aftermath of a riot or the contents of a disorganised storage room. In fact it is Jesse Darling’s winning submission for the 2023 Turner Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious art awards. The prize was established to honour the ‘innovative and controversial’ works of J.M.W. Turner, although in the thirty-nine years since its inauguration, none of the winning submissions have evoked the sublime beauty of Turner’s paintings.

There are no facts when it comes to art, only opinions. The judges, who lauded the exhibition for ‘unsettl[ing] perceived notions of labour, class, Britishness and power’, seem to have glimpsed something profound beyond the shallow display of metal and tape. Or they may simply have considered it the least worst submission in a shortlist which included some accomplished but otherwise unremarkable charcoal sketches, an oratorio about the COVID-19 pandemic and a few pipes.

It may be that beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder. But there is a distinction to be made between works of art whose beauty is universally accepted, and those which fail to find acclaim beyond a small demographic of urban, middle-class bohemians. According to a YouGov poll, an unsurprising 97% of the British public consider the Mona Lisa to be a work of art. That figure drops to 78% for Picasso’s Guernica, 41% for Jackson Pollock’s Number 5, and just 12% for Tracey Emin’s My Bed. That 12% of society, however, represents those among us most likely to work in art galleries and institutions, and to hold the most latitudinarian definition of ‘art’.

For ordinary people, the chief criterion for art is, and always has been, beauty. But like the other humanities, the 20th century saw the art world succumb to the nebulous web of ‘discourse’, with a corresponding shift away from aesthetic merits and towards political ends. Pieces like Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain – an upturned porcelain urinal – proved that works of art could shoot to fame precisely on account of their capacity to disturb and agitate audiences. As philosopher Roger Scruton described it, ‘According to many critics writing today a work of art justifies itself by announcing itself as a visitor from the future. The value of art is a shock value.’ The fact that shock, fear and revulsion create more powerful reactions than the sense of joy, calm or awe one feels when looking at a Rosetti or a Caravaggio is an unfortunate fact of human nature, and remains as true today as it did a hundred years ago. In much the same way that a news stories about declining global poverty rates or deaths from malaria will receive less attention than stories about melting ice caps or rising CO2 emissions, a truly beautiful artwork will receive less attention in the media than something which irks, irritates and offends.

In the opening chapter of The Picture of Dorian Gray, when Basil Hallward reveals the eponymous portrait to his friend Lord Henry, he confesses to feeling reservations about exhibiting the work despite it being, in Henry’s estimation, his masterpiece. ‘There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about,’ Lord Henry reprimands him, ‘and that is not being talked about.’ The sentiment is triply true in the age of social media. Indeed, the term ‘ragebait’ started appearing online in the months following Mark Leckey’s winning submission for the Turner Prize in 2008, an exhibition which featured a glow-in-the-dark stick figure and a naked mannequin on a toilet. Like Dorian Gray, the more the art world thirsts for attention, the more hideous the art itself will become.

The quickest route to attention is politics. At the award ceremony for this year’s Turner Prize, Darling pulled from his pocket a Palestinian flag, ‘Because there’s a genocide going on and I wanted to say something about it on the BBC.’ In his acceptance speech, he lambasted the late Margaret Thatcher for ‘pav[ing] the way for the greatest trick the Tories ever played, which is to convince working people in Britain that studying, self expression and what the broadsheet supplements describe as “culture” is only for certain people in Britain from certain socio-economic backgrounds. I just want to say don’t buy in, it’s for everyone’. The irony is that all the money in the world wouldn’t fix the problems currently afflicting the art scene. If the custodians of modern art want to democratise their vocation, and make culture available to ordinary people, they should follow the example of Turner – and produce something worth looking at.

The Post-Polar Moment

Introduction

Abstract: Nations and intergovernmental organisations must consider the real possibility of moving into a world without a global hegemon. The core assumptions that underpin realist thought can directly be challenged by presenting an alternative approach to non-polarity. This could be through questioning what might occur if nations moved from a world in which polarity remains a major tool for understanding interstate relations and security matters. Further work is necessary to explore the full implications of what entering a non-polar world could mean and possible outcomes for such events.

Problem statement: What would global security look like without competition between key global players such as the People’s Republic of China and the United States?

So what?: Nations and intergovernmental organisations should prepare for the real possibility that the international community could be moving into a world without a global hegemon or world order. As such, they should recognise the potential for a rapidly changing geopolitical landscape and are urged to strategically acknowledge the importance of what this would mean. More research is still needed to explore the implications for and of this moving forward.

Geopolitical Fluidity

Humankind has moved rapidly from a period of relatively controlled geopolitical dominance towards a more fluid and unpredictable situation. This has posed a question to global leadership: what would it mean to be leaderless, and what role could anarchy play in such matters? Examining the assumptions that make up most of the academic discourse within International Relations and Security Studies remains important in trying to tackle said dilemma.

From this geopolitical fluidity, the transition from U.S.-led geopolitical dominance, shown in the ‘unipolar moment’, to that of either bipolarity or multipolarity has come about. This re-emergence, however, has not directly focused on an unexplored possibility that could explain the evolving trends that might occur. Humankind is entering a post-polar world out of the emergence of a leaderless world structure. There is the possibility, too, that neither the U.S. nor the the People’s Republic of China become the sole global superpower which then dominates the world and its structures”. The likelihood of this occurring remains relatively high, as explored further on. Put differently, “it is entirely possibly that within the next two decades, international relations could be entering a period of no singular global superpower at all”.

Humankind is entering a post-polar world out of the emergence of a leaderless world structure.

The Non-Polar Moment

The most traditional forms of realism propose three forms of polar systems. These are unipolar, bipolar, or multipolar (The Big Three). There is a strong possibility that we as a global community are transitioning into a fourth and separate world system. This fourth and relatively unexplored world system could mean that anything that enables the opportunity for either a superpower or regional power to establish itself will not be able to occur in the foreseeable future.

It can also historically be explained by the end of the Cold War and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, which led to the emergence of the U.S. as the leading superpower within global politics. For lack of better words, it was a generational image of a defining dominant nation within both international relations and security circles. From this, it was widely acknowledged and regarded that Krauthammer coined the’ unipolar moment’ in the aftermath of the Cold War. This meant that there was a period when the U.S. was the sole dominant centre of global power/polarity. This unipolar moment is more accurately considered part of a much larger ‘global power moment’.

This global power moment is in reference to the time period mentioned above, which entailed the ability for nations to directly and accurately project their power abroad or outside their region. This ability to project power will presumably but steadily decline in the following decades due to the subsequent decrease in the three core vectors of human development (Demography, Technology and Ideology). When combined, one could argue that the three polar systems allowed for the creation of the global power moment itself. Specifically, that would be from the start of the 19th until the end of the 20th century. Following that line of thought, the future was affected by the three aforementioned pillars somewhat like this:

- Demography: this means having a strongly structured and or growing population, one that allows a nation to act expansively towards other states and use those human resources to achieve its political goals.

- Technology: the rise of scientific innovations, allowing stronger military actions to happen against other nations. To date, it has granted nations the ability to directly project power abroad, which, before this, would have only been able to occur locally or at a regional level.

- Ideology: the third core vector of human development. That means the development of philosophies that justify the creation of a distinct mindset or “zeitgeist” that culturally explains a nation’s actions.

These three core vectors of development are built into a general human trend and assumption of ‘more’, within this great power moment. Existing systems are built into the understanding of more people, more technology development, and more growth, along with possessing generated ideologies that rationalise such actions. What this does, in turn, is help define a linear progression of human history and help develop an understanding of interstate relations.

Existing systems are built into the understanding of more people, more technology development, and more growth, along with possessing generated ideologies that rationalise such actions.

Nevertheless, this understanding is currently considered insufficient; the justification for this is based on developing a fourth vector to help comprehend power distribution. This vector is that of non-polarity, meaning a non-power-centred world structure. From this, the idea or concept of non-polarity is not original. Previously, it was deconstructed by Haass, Manning and Stuenkel, and, in their context, refers to a direct absence of global polarity within any of the Big Three polar systems.

Prior academics have shown that non-polarity is the absence of absolute power being asserted within a place and time but continues to exist within other big three polar systems. The current world diverges from the idea of multipolar in one core way. There are several centres of power, many of which are non-state actors. As a result, power and polarity can be found in many different areas and within many different actors. This argument expands on Strange’s (1996) contributions, who disputed that polarity was transferring from nations to global marketplaces and non-state actors.

A notable example is non-state players who act against more established powers, these can include terrorist and insurgent groups/organisations. Non-polarity itself being “a world dominated not by one or two or even several states but rather by dozens of actors possessing and exercising various kinds of power”. From this, a more adequate understanding of non-polarity is required. Additionally, it should be argued that non-polarity is rather a direct lack of centres of power that can exist and arise from nations. Because of this, this feature of non-polarity infers the minimisation of a nation’s ability to meaningfully engage in structural competition, which in turn describes a state of post-polarity realism presenting itself.

Humans are presented with the idea of a ‘non-polar moment’, which comes out of the above-stated direct lack of polarity. The non-polar moment inverts the meaning of the unipolar moment found with the U.S. in the aftermath of the Cold War, which was part of the wider period of Pax Americana (after WWII). This contrasts with the traditional idea: instead of having a singular hegemonic power that dominates power distribution across global politics, there is no direct power source to assert itself within the system. Conceptually, this non-polar moment could be viewed as a system where states are placed into a situation in which they are limited to being able to act outwardly. A reason why they could be limited is the demographic constraints being placed on a nation from being able to strategically influence another nation, alongside maintaining an ideology that allows nations to justify such actions.

The non-polar moment inverts the meaning of the unipolar moment found with the U.S. in the aftermath of the Cold War, which was part of the wider period of Pax Americana.

The outcomes of such a world have not been fully studied, with the global community moving from a system to one without any distributors of power or ability to influence other nations. In fact, assuming these structural conditions, -that nations need to acquire hegemony and are themselves perpetually stunted-, the scenario is similar to having a ladder that is missing its first few steps. From this, one can also see this structural condition as the contrast to a ‘rising tide lifts all boats’ situation, with the great power reduction. Because of this, the non-polar moment could symbolise the next, fourth stage for nations to transition to part of a much wider post-polarity form of realism that could develop.

The implications for this highlight a relevant gap within the current literature, the need to examine both the key structural and unit-level conditions that currently are present. This is what it might mean to be part of a wider ‘a global tribe without a leader’, something which a form of post-polarity realism might suggest.

A Global Tribe Without a Leader

To examine the circumstances for which post-polarity realism can occur, one must examine the conditions that define realism itself. Traditionally, for realism, the behaviours of states are as follows:

- States act according to their self-interests;

- States are rational in nature; and

- States pursue power to help ensure their own survival.

What this shows is that there are several structures from within the Big Three polar systems. Kopalyan argues that the world structure transitions between the different stages. This can be shown by moving between interstate relations as bipolar towards multipolar, done by both nations and governments, which allows nations to re-establish themselves in accordance with their structural conditions within the world system. Kopalyan then continues to identify the absence of a consistent conceptualisation of non-polarity. This absence demonstrates a direct need for clarity and structured responses to the question of non-polarity.

As such, the transition between systems to non-polarity, to and from post-polarity will probably occur. The reason for this is the general decline in three core vectors of human development, which are part of complex unit-level structural factors occurring within states. The structural factors themselves are not helpful towards creating or maintaining any of the Big Three world systems. Ultimately, what this represents is a general decline in global stability itself which is occurring. An example of this is the reduction of international intergovernmental organisations across the globe and their inability to adequately manage or solve major structural issues like Climate Change, which affects all nations across the international community.

Firstly, this can be explained demographically because most nations currently live with below-replacement (and sub-replacement) fertility rates. In some cases, they have even entered a state of terminal demographic decline. This is best symbolised in nations like Japan, Russia, and the PRC, which have terminal demographics alongside most of the European continent. The continuation of such outcomes also affects other nations outside of this traditional image, with nations like Thailand and Türkiye suffering similar issues. Contrasted globally, one can compare it to the dramatic inverse fertility rates found within Sub-Saharan Africa.

Secondly, with technology, one can observe a high level of development which has produced a widespread benefit for nations. Nevertheless, it has also contributed to a decline in the preservation of being able to transition between the Big Three systems. Technological developments have produced obstacles to generating coherence between governments and their citizenry. For example, social media allows for the generation of mass misinformation that can be used to create issues within nations from other countries and non-state actors. Additionally, it has meant that nations are placed permanently into a state of insecurity because of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). The results mean there can never be any true sense or permanence in the idea of security due to the effects of WMDs and their spillover effects. Subsequently, technological development has placed economic hurdles for nations within the current world order through record levels of debt, which has placed further strain on the validity of the current global economic system in being able to maintain itself.

Technological developments have produced obstacles to generating coherence between governments and their citizenry.

The final core vector of human development is ideology and its decline. This has been shown with a reduction in the growth of new ideologies and philosophies used to understand and address world issues. This is an extension of scholars like Toynbee and Spengler, whose literature has also claimed that ideologically, the world has witnessed a general reduction in abstract thought and problem-solving. This ideological decline has most substantially occurred in the Western World.

The outcomes of the reduction in these human development vectors demonstrate a potential next stage in global restructuring. Unfortunately, only little data can be sourced to explain what a global world order could look like without a proverbial ‘king on the throne’ exists. Nearly all acquired data is built into a ‘traditional’ understanding of a realist world order. This understanding is largely correct. Nevertheless, the core assumption built into our post-WWII consensus is out of date.

This is the concept that we as nations will continue falling back into and transitioning between the traditional Big Three polar systems. This indeed contrasts with moving into a fourth non-polar world structure. Traditionally, states have transitioned between the Big Three world systems. This can only occur when all three vectors of human development are positive, when now, in reality, all three are in decline.

This is not to take away from realism as a cornerstone theoretical approach to understanding and explaining state behaviour. Realism and its core tenets are still correct on a conceptual and theoretical level and will remain so. Indeed, what unites all branches of realism is this core assumption of civilisation from within the system and that it will directly affect polarity. These structures are assumed to remain in place, presenting one major question. This question is shown upon investigating the current bipolar connection between both major superpowers, in this case, between the U.S. and the PRC. Kissinger argues that “almost as if according to some natural law, in every century, there seems to emerge a country with the power, the will, and the intellectual and moral impetus to shape the entire international system per its own values.” It can be seen in the direct aftermath of the declining U.S., which is moving away from the unipolar moment it found itself in during the 1990s, into a more insecure and complex multipolar present. This present currently defines Sino-U.S. relations and has set the tone for most conversations about the future of global politics. Such a worldview encapsulates how academics have traditionally viewed bipolar strategic competition, with one side winning and the other losing. This bipolarity between these superpowers has often left the question of which will eventually dominate the other. Will the U.S. curtail and contain a rising PRC, or will the PRC come out as the global hegemon overstepping U.S. supremacy?

Realism and its core tenets are still correct on a conceptual and theoretical level and will remain so. Indeed, what unites all branches of realism is this core assumption of civilisation from within the system and that it will directly affect polarity.

Consequently and presently, there remains a distinct possibility that both superpowers could collapse together or separately within a short period of each other. This collapse is regardless of their nation’s relative power or economic interdependence. It could rather be:

- The PRC could easily decline because of several core factors. Demographically, the nation’s one-child policy has dramatically reduced the population. The results could place great strain on the nation’s viability. Politically, there is a very real chance that there could be major internal strife due to competing factional elements within the central government. Economically, housing debt could cause an economic crash to occur.

- For the U.S., this same could occur. The nation has its own economic issues and internal political problems. This, in turn, might also place great pressure on the future viability of the country moving forward.

Still, the implications for both nations remain deeply complex and fluid as to what will ultimately occur. From this, any definite outcomes currently remain unclear and speculative.

Within most traditional Western circles, the conclusion for the bipolar competition will only result in a transition towards either of the two remaining world systems. Either one power becomes hegemonic, resulting in unipolarity, or, in contrast, as nations move into a multipolar system, where several powers vie for security. Nevertheless, this transition cannot currently occur if both superpowers within the bipolar system collapse at the same time. This is regardless of whether their respective collapses are connected or not. As both superpowers are in a relative decline, they themselves contribute to a total decline of power across the world system. From this, with the rise of global interdependence between states, when a superpower collapses, it has long-term implications for the other superpower and those caught in between. If both superpowers collapse, it would give us a world system with no definitive power centre and a global tribe without a leader.

This decline would go beyond being in a state of ‘posthegemony’, where there is a singular or bipolar superpower, the core source of polarity amongst nations, towards that of a non-polar world. This means a transition into a world without the ability to develop an organised world system from a full hegemonic collapse. With the collapse of bipolarity and the inability to transition towards either of the traditional remaining world systems, as previously mentioned, this would be like all nations being perpetually stunted in their ability to develop, like a ladder with the first ten steps missing. All nations would collectively struggle to get up the first few steps back into some form of structural normalcy. It could, for decades, prevent any attempt to transition back into the traditional realm of the Big Three world systems.

With the collapse of bipolarity and the inability to transition towards either of the traditional remaining world systems, as previously mentioned, this would be like all nations being perpetually stunted in their ability to develop, like a ladder with the first ten steps missing.

The result/consequence of any collapse directly caused by a link between economic, demographic and political failings would become a global death spiral, potentially dragging nearly all other nations down with its collapse. That considered another question would arise: if we as an international community structurally face a non-polar moment on a theoretical level, what might the aftermath look like for states and interstate relations?

Rising and Falling Powers

This aspect of how the international community and academia view the international sphere could yield a vital understanding of what may happen within the next few years and likely decades, will need to constantly reassess the core assumptions behind our pre-existing thoughts. One core assumption is that nations are either rising or falling. However, it may be worth remembering that it is entirely possible that both bipolar powers could easily decline significantly at any point, for multiple different reasons and factors. The outcomes would have substantial implications for the world as a whole.

It may be worth remembering that it is entirely possible that both bipolar powers could easily decline significantly at any point, for multiple different reasons and factors.

Ultimately, it implies that the international community will need to reevaluate how issues like polarity are viewed, and continue to explore the possibility of entering a fourth polar world – non-polar – and address the possibility that some form of post-polarity realism might begin to conceptualise. Nations and intergovernmental organisations should, at the least, attempt to consider or acclimatise to the real possibility of transforming into a world without a global hegemon or world order.

This article was originally published in The Defence Horizon Journal, an academic and professional-led journal dedicated to the study of defence and security-related topics. The original post can be read here.

Kino

Oligarchic Oafs

British cultural critics, in my opinion, suffer from an insularity which prevents them from connecting the events of their own country to any wider patterns of civilisation. This is truest for those who are the most correct with their criticisms. Take for example Theodore Dalrymple, whose 1998 article Uncouth Chic in the City Journal was prophetic in diagnosing a distinctly British pathology. I give a lengthy quote to showcase the depth of his description:

“The signs — both large and small — of the reversal in the flow of aspiration are everywhere. Recently, a member of the royal family, a granddaughter of the queen, had a metal stud inserted into her tongue and proudly displayed it to the press. (…) Middle-class girls now consider it chic to sport a tattoo — another underclass fashion, as a visit to any British prison will swiftly establish. (…) Advertising now glamorizes the underclass way of life and its attitude toward the world. Stella Tennant, one of Britain’s most famous models and herself of aristocratic birth, has adopted almost as a trademark the stance and facial expression of general dumb hostility to everything and everybody that is characteristic of so many of my underclass patients.”

Dalrymple lays the blame for this “uncouth chic” on moral relativism: “… since nothing is better and nothing is worse, the worse is better because it is more demotic.” This much may be true, but it sidesteps an important matter. There’s an area where the British remain elitists: money. Whatever relativism now reigns upon our morality, it has areas of preferred emphasis. With manners we are relativists, but with cash we are a nation of absolutists who think being rich is better than being poor. Indeed, the very need to transform the uncouth into a type of chic (a word meaning sophisticated and fashionable) betrays such a mindset. Nobody is demanding unfashionable uncouth trash.

To be an elitist about your wallet and a vulgarian about your manners. I wager this combination isn’t accidental but vital. The latter flows from the former.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle, who defines a lot of things near-finally, defines an oligarch as someone who is both wealthy and has a wealth-based idea of goodness. That is, an oligarch isn’t just rich; he thinks being rich is identical with being good. This is why he thinks only the rich should hold political office, for example. So, it’s not that money is the root of all evil and the rich the wickedest. The one who has his character in order only benefits the more money he has, because he understands money as a tool for acquiring other goods. The oligarch grasps for money like an idolum and hates anybody who doesn’t have it.

But why does the oligarch think this? Hasn’t he observed all the good poor people in the world? Is he blind to the honest pauper? Aristotle’s answer is simple: the oligarch thinks money equals goodness because he thinks living well is gorging every appetite with no limit. “For where enjoyment consists in excess, men look for that skill that produces the excess that is enjoyed”[ii]. In other words, if the good of life is endless pleasure, and endless pleasure needs endless money to buy it, the good of life requires endless money. Those without money are unable to get endless pleasure, so the oligarch looks down on their lives as inferior.

The collection of norms we call “etiquette” or “manners” have emerged organically over a long period. Some are obviously arbitrary or meant to exclude people unjustly (the outmoded and snobbish dress code of “no brown in town” comes to mind). But a great many are there to limit personal behaviour, to channel action into a disciplined pattern.

Why chew with your mouth closed? Because it shows consideration for your fellow diners. Why take small bites? Because it controls you to eat at a healthy pace. Why not deliberately get drunk? To not impair your reason. Why avoid constant use of foul language? To show that your mind dwells on higher things than bodily functions. In all these there’s a standard of excellence, mental or physical, drilled into the person through control of their actions.

It’s a principle properly summarised in a line from Confucius: “Therefore the instructive and transforming power of ceremonies is subtle; they stop depravity before it has taken form, causing men daily to move towards what is good, and keep themselves farther apart from guilt, without being themselves conscious of it.”.

Is there then any reason for an oligarch to cultivate manners? I think none of weight. An oligarch might make a show of good manners, if he thinks this displays wealth. But once the cultural association of money with good manners is gone, he’ll stop this act. An oligarch who sees money as the means to swelling himself with pleasure actually has an incentive not to cultivate manners. Why would he cultivate something designed to limit his appetites? If the purpose of eating is to shovel as much food into your mouth as possible, and not to nourish yourself, then you can dispense with the cutlery, even possibly the plate.

But this leads to a further thought. Money for its own sake is necessarily vulgar because any constraint on it points to a standard other than pleasure. If we accept that the manners and etiquette we call aristocratic have developed over time as a way of disciplining wealth into excellence, then an oligarchy engorged on pleasure must reject them. Rather, manners that the underclass have adopted out of lack of correction or poverty now become the fascinations of the rich. A poor man wears ragged jeans because he can’t afford anything else. An oligarch wears designer torn jeans because money compels him to wear whatever he wants however he likes it. The expression of “general dumb hostility” which Dalrymple notes, may have been born from the Hobbesian nightmare of a slum; but for an oligarch, it’s the hostility of wealth to any external correction.

In an oligarchic society the top and bottom begin to resemble each other in customs even as they drift apart in income, and even as the top despises the bottom. We may explain the vulgarity of British elites in terms of class guilt, demoralisation, or political posturing. But the issue remains that love of gold doesn’t protect you from barbarism. It’s the passion that unites the highest emperor with the coarsest bandit.

Orwell’s Egalitarian Problem

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is a book whose influence exceeds its readership. It resembles a Rorschach test; moulding itself to the political prejudices of whoever reads it. It also has a depth which often goes unnoticed by those fond of quoting it.

The problem isn’t that people cite Orwell, but that people cite Orwell in a facile and cliched manner. The society of Oceania which Orwell creates isn’t exemplified in any contemporary state, save perhaps wretched dictatorships like North Korea or Uzbekistan. It’s thus not my intent to draw on Nineteen Eighty-Four to indict my own society as being “Orwellian” in the sense of being a police state, a procurer of terror, or engaged in centralised fabrication of history. A world of complete totalitarianism of the Hitlerian or Stalinist kind hasn’t arrived (not yet at least), but Nineteen Eighty-Four still has insights applicable to our day.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the protagonist, Winston, is suffocated by the miserable tyranny he lives in. The English Socialist Party (INGSOC) controls all aspects of Britain, now called Airstrip One, a province of the state of Oceania. It does so in the name of their personified yet never seen dictator, Big Brother. When Winston is almost at breaking point, he meets fellow party member, O’Brien. O’Brien, Winston thinks, is secretly a member of the resistance, a group opposing Big Brother. O’Brien hands Winston a book called The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism. This book is supposedly written by Emmanuel Goldstein, arch-nemesis of Big Brother, and details the secret history and workings of Oceanian society, something unknown to all its citizens.

Oligarchic collectivism is the book’s term for the ideology of the Party in response to a repeating historical situation. Previous societies were characterised by constant strife between three social classes: the top, the middle, and the bottom. The pattern of revolution across history was always the middle enlisting the bottom by pandering to their base grievances. The middle would use the bottom to overthrow the top, install itself as the new top, and push the bottom back down to their previous place. A new middle would form over time, and the process would repeat.

INGSOC overthrew the top through a revolution, in the name of equality. What it actually achieved was collectivised ownership at the top, and so it created a communism of the few, not unlike classical Sparta. The rest of the population, derogatorily called “proles”, live in squalid poverty and are despised as animals. They’re kept from rebelling by being maintained in ignorance and given cheap hedonistic entertainment at the Party’s expense. INGSOC nominally rules on their behalf, but in reality is built upon their continual oppression. As Goldstein’s book puts it:

“All past oligarchies have fallen from power either because they ossified or because they grew soft. Either they became stupid and arrogant, failed to adjust themselves to changing circumstances, and were overthrown; or they became liberal and cowardly, made concessions when they should have used force, and once again were overthrown. They fell, that is to say, either through consciousness or through unconsciousness.”

In other words, the top falls either by failing to notice reality and being overthrown once reality crashes against it, or by noticing reality, trying to create a compromise solution, and being overthrown by the middle once they reveal their weakness. INGSOC, however, lasts indefinitely because it has discovered something previous oligarchies didn’t know:

“It is the achievement of the Party to have produced a system of thought in which both conditions can exist simultaneously. And upon no other intellectual basis could the dominion of the Party be made permanent. If one is to rule, and to continue ruling, one must be able to dislocate the sense of reality. For the secret of rulership is to combine a belief in one’s own infallibility with the Power to learn from past mistakes.”

INGSOC can simultaneously view itself as perfect, and effectively critique itself to respond to changing circumstances. It can do this, we are immediately told, through the principle of doublethink: holding two contradictory thoughts at once and believing them both:

“In our society, those who have the best knowledge of what is happening are also those who are furthest from seeing the world as it is. In general, the greater the understanding, the greater the delusion; the more intelligent, the less sane.”

It’s through this mechanism that the Party remains indefinitely in power. It has frozen history because it can notice gaps between its own ideology and reality, yet simultaneously deny to itself that these gaps exist. It can thus move to plug holes while retaining absolute confidence in itself.

At the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Inner Party member O’Brien tortures Winston, and reveals to him the Party’s true vision of itself:

“We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means, it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship. The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power. Now do you begin to understand me?”

It’s here where I part ways with Orwell. For a moment, O’Brien has revealed to Winston one-half of what Inner Party members think. Doublethink is the simultaneous belief in the Party’s ideology, English Socialism, and in the reality of power for its own sake. INGSOC is simultaneously socialist and despises socialism. Returning to Goldstein’s book:

“Thus, the Party rejects and vilifies every principle for which the Socialist movement originally stood, and it chooses to do this in the name of Socialism. It preaches a contempt for the working class unexampled for centuries past, and it dresses its members in a uniform which was at one time peculiar to manual workers and was adopted for that reason.”

Orwell creates this situation because, as a democratic socialist, he’s committed to the idea of modern progress. The ideal of equality of outcome isn’t bad, but only the betrayal of this ideal. Orwell critiques the totalitarian direction that the socialist Soviet Union took, but he doesn’t connect this to egalitarian principles themselves (the wish to entirely level society). He therefore doesn’t realise that egalitarianism, when it reaches power, is itself a form of doublethink.

To see how this can be we must introduce an idea alien to Orwell and to egalitarianism but standard in pre-modern political philosophy: whichever way you shake society, a group will always end up at the top of the pile. Nature produces humans each with different skills and varying degrees of intelligence. In each field, be it farming, trade or politics, some individuals will rise, and others won’t.

The French traditionalist-conservative philosopher Joseph de Maistre sums up the thought nicely in his work Etude sur La Souveraineté: “No human association can exist without domination of some kind”. Furthermore, “In all times and all places the aristocracy commands. Whatever form one gives to governments, birth and riches always place themselves in first rank”.

For de Maistre the hard truth is, “pure democracy does not exist”. Indeed, it’s under egalitarian conditions that an elite can exercise its power the most ruthlessly. For where a constitution makes all citizens equal, there won’t be any provision for controlling the ruling group (since its existence isn’t admitted). Thus, Rome’s patricians were at their most predatory against the common people during the Republic, while the later patricians were restrained by the emperors, such that their oppression had a more limited, localised effect.

If we assume this, then the elite of any society that believes in equality of outcome must become delusional. They must think, despite their greater wealth, intelligence and authority, that they’re no different to any other citizen. Any evidence that humans are still pooling in the same hierarchical groups as before must be denied or rationalised away.

This leads us back to the situation sketched in Goldstein’s book. What prevents the Party from being overthrown is doublethink. The fact it can remain utterly confident in its own power, and still be self-critical enough to adapt to circumstances. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the former is exemplified in the vague utopian ideology of INGSOC, while the latter is the cynical belief in power for its own sake and willingness to do anything to retain it. But against this, no cynical Machiavellianism is necessary to form one-half of doublethink. A utopian egalitarian with privilege is doublethink by default. At once, he believes in the infallibility of his ideology (he must if he’s to remain in it), and is aware of his own status, continually acting as one must when in a privileged position.

How does this connect to that most Orwellian scenario, the permanent hardening in place of an oligarchic caste that can’t be removed? As Orwell says through Goldstein, ruling classes fall either by ossifying to the point they fail to react to change, or by becoming self-critical, trying to reform themselves, and exposing themselves to their enemies. Preventing both requires doublethink: knowing full well that one’s ideology is flawed enough to adapt practically to circumstances and believing in its infallibility. The egalitarian elite with a utopian vision has both covered. If you truly, genuinely, believe that you’re like everyone else (which you must if you think your egalitarian project has succeeded), you won’t question the perks and privileges you have, since you think everybody has them. That takes care of trying to reform things: you don’t.

Yet, as an elite, you still behave like an elite and take the necessary precautions. You avoid going through rough areas, you pick only the best schools for your offspring, and you buy only the best houses. As an elite, you also strive to pass on your ideology and way of life to the next generation, thus replicating your group indefinitely. Thus, you simultaneously defend your position and believe in your own infallibility.

Could an Oceanian-style oligarchy emerge from this process? Absolutely, provided we qualify our meaning. The society of Nineteen Eighty-Four lacks any laws or representational politics. It has no universal standards of education or healthcare. It functions as what Aristotle in Politics calls a lawless oligarchy, with the addition of total surveillance. But this is an extreme. What I propose is that egalitarianism, once in power, necessarily causes a detachment between ideology and reality that, if left to itself, can degenerate into extreme oligarchy. The severe doublethink needed to sustain both belief in the success of the project and safeguard one’s position at the top can accumulate over time into true class apartheid. This is, after all, exactly what happened to the Soviet Union. As the Soviet dissident and critic Milovan Dilas, in his book The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System, put it:

“Every private capitalist or feudal lord was conscious of the fact that he belonged to a special discernible social category. (…) A Communist member of the new class also believes that, without his part, society would regress and founder. But he is not conscious of the fact that he belongs to a new ownership class, for he does not consider himself an owner and does not take into account the special privileges he enjoys. He thinks that he belongs to a group with prescribed ideas, aims, attitudes and roles. That is all he sees.”

To get an Oceanian scenario, you don’t need egalitarianism plus a Machiavellian will to power, forming two halves of doublethink. You just need egalitarianism.

Neoconservatism: Mugged by Reality (Part 2)

The Neoconservative Apex: 9/11 and The War on Terror

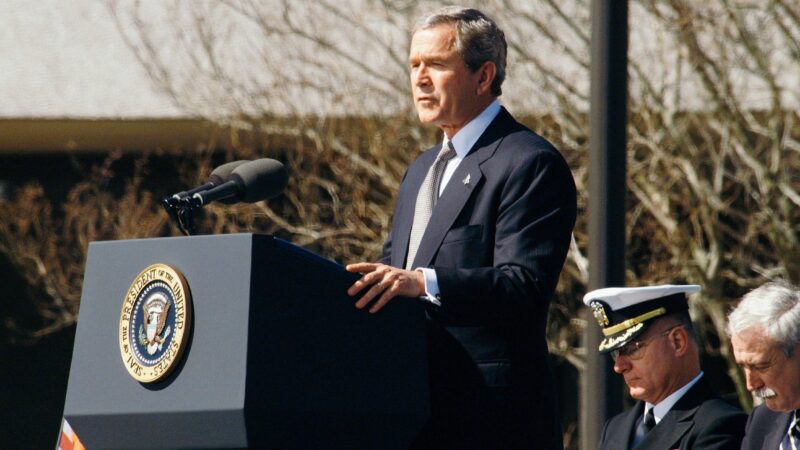

11th September 2001 was a watershed moment in American history. The destruction of the World Trade Centre by Muslim terrorists, the deaths of thousands of innocent American citizens and the general feeling of chaos and vulnerability was enough to turn even the cuddliest of liberals into bloodthirsty war hawks. People were upset, confused and above all angry and wanted someone to pay for all the destruction and death. To paraphrase Chairman Mao, everything under the heavens was in chaos, for the neoconservatives the situation was excellent.

After 9/11, President Bush threw out the positions on foreign policy that he’d advocated for during his candidacy and became a strong advocate of using US military strength to go after its enemies. The ‘Bush Doctrine’ became the staple of US foreign policy during Bush’s time in office and the magnum opus of the neoconservative deep state. The doctrine stated that the United States was entangled in a global war of ideas between Western values on the one hand, and extremism seeking to destroy them on the other. The doctrine turned US foreign policy into a black and white war of ideology where the United States would show leadership in the world by actively seeking out the enemies of the West and also change those countries into becoming like the West. Bush stated in his 2002 State of the Union speech:

“I will not wait on events, while dangers gather. I will not stand by, as peril draws closer and closer. The United States of America will not permit the world’s most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world’s most destructive weapons.”

The ‘Bush Doctrine’ was a pure expression of neoconservatism. But the most crucial part of his speech was when he gave a name to the new war the American state had begun to wage:

“Our war on terror is well begun, but it is only begun. This campaign may not be finished on our watch – yet it must be, and it will be waged on our watch.”

The ‘War on Terror’ became a term that would become synonymous with the Bush years and indeed neoconservatism. For neoconservatives, the attack on 9/11 reaffirmed their pessimism about the world being hostile to the United States and, in turn, their views on needing to eradicate it with ruthless calculation and force. A new doctrine, a new President, a new war – neoconservatism certainly held itself up to its ‘neo’ nature. With all this set-in place and the neoconservative deep state rearing to go, they could finally start to do what they had always wanted to do – wage war.

Iraq and Afghanistan became the main targets, with Al Qaeda, Saddam Hussein and the Taliban becoming public enemy’s number one, two and three. A succession of invasions into both countries, supported by the British military, ended up with the West looking victorious. Both the Taliban and Saddam Hussein had been removed from power, Al Qaeda was on the run, and various of their top leaders had been captured or killed. It was ‘mission accomplished’ and thus time to remould Afghanistan and Iraq into American-aligned liberal democracies. Furthermore, the new neoconservative elite saw to demoralise and outright destroy all those who had been associated with the Hussein regime and Islamic radical groups and thus began a campaign of hunting down, imprisoning and ‘interrogating’ all those involved. However, this is where the neoconservative project would begin to fall as quickly as it had ascended.

The Failure and Eventual Fall of Neoconservatism

A core factor to note is that the neoconservative belief that one could simply invade non-democratic and often heavily religious countries and flip them into liberal democracies proved to be highly utopian. As Professor Ian Shapiro pointed out in his Yale lecture on the Demise of Neoconservatism Dream, the neoconservative’s falsely believed that destroying a country’s military was equivalent to pacifying and ruling a country. The American-British coalition may have swiftly destroyed the armies of Hussein of Iraq and cleared out the Taliban in Afghanistan but they did not effectively destroy the support both had amongst the general population. If anything, the removal of both created an array of intense power vacuums which the neoconservatives could only seem to fill with corrupt American aligned Middle Eastern politicians as well as gun-ho Generals and neoconservative elites who knew very little about the countries they were presiding over.

One such example is Paul Bremer who led the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in Iraq after the Hussein regime was overthrown. His genius idea – that totally would get the Iraqi people on the side of freedom and democracy – was to disband the army and eradicate the Iraqi civil service and governmental authorities of those who were aligned with Hussein’s Ba’ath Party; terming it De-Ba’athification. Both led to a plethora of Iraqi’s losing their jobs and incomes and being smeared as enemies of the new American led regime – even low level teachers and privates were removed despite the fact that many of them joined the party simply to keep their own jobs.

While seen as a tactical way in which to remove any potential opposition to the CPA, the move created more opposition to the new government than any dissident anti-American group could have wished to have created – turns out making 400,000 young men, who know how to kill a man in sixteen different ways, unemployed isn’t the best way in which to show your care for the Iraqi people. It also didn’t help that Bremer and the CPA failed to account for a variety of funds and financial given to him for the reconstruction of Iraq, leading to a variety of financial blackholes and millions of dollars that simply disappeared.

Insurgent groups grew and assassination attempts on Bremer became commonplace to such an extent that even Osama Bin Laden himself placed a sizable bounty on Bremer’s head. Opposition to Bremer was so fervent that he was essentially forced to leave his position in the CPA by mid-2004 with his legacy being one of failure, instability and corruption, a legacy which the Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich called “the largest single disaster in American foreign policy in modern times”.

Removing opposition instead of attempting to work with it and use their expertise is something the US has done before, especially after WW2 with the fall of the Axis regimes, but the neoconservative mind has no tolerance or time for those who oppose American values – leading to brutal methods being used against those who do not comply.

It was under the neoconservatives that Guantanamo Bay was opened, a prison known for its mistreatment of prisoners and dubious torture methods. It was under the neoconservatives that Abu Ghraib prison, a feared prison under Hussein’s regime, became a place in which American soldiers and state officials were allowed treat and use interrogation methods on prisoners in manners that violate basic human dignity. And it was under the neoconservatives that began a mass surveillance state in their own country via the so-called ‘Patriot Act’ which put the privacy of American citizens in great danger. The Bush administration claimed that these abuses of human rights were not indicative of US policy, they were and the neoconservatives were the one’s responsible.

Luckily, these abuses were quickly all over mainstream news both inside and outside the US and horrified the population at large, even those who had once been pro the War on Terror. Furthermore, soldiers who had fought abroad came back with horror stories of their fellow soldiers abusing prison inmates and how they’d left Iraq bombed to the ground, displacing families and with casualty rates of up to and around 600,000 Iraqi civilians. The American mood turned against the war and by the end of Bush’s tenure in office 64% of Americans felt that the Iraq war had not been worth fighting.

The average American who felt angry and upset at their freedoms being threatened by Islamic terrorism became just as angry and upset when they saw their own country committing atrocities and taking away the freedoms of others. While it may seem cliche to point out the hypocrisy, this was one of the first times American’s had been exposed to the reality of what their state was really capable of. As Shapiro elucidates, the real legacy of the Iraq war and the War on Terror is that it destroyed America’s moral high ground. A high ground America has never been able to reach to since.

Barrack Obama and the Democrats attacked the Republicans and their neoconservative wing for their human rights abuses, the unjustified invasion of Iraq and implosion of America’s moral standing on the international stage. It is not unfair to say that Obama’s intoxicating charm and message of hope for America was desperately wanted in a post-Bush era in order so that Americans could try and forget the depravities that their country had fallen to in the early 2000s. He promised to pull out of Iraq, close Guantanamo Bay and replace the neoconservative doctrine for one based on diplomacy and moderation.

Bush and the majority of his neoconservatives left office after the election of Obama – in which he beat the then darling of the neoconservative right John McCain – and have since failed to re-enter the halls of power or indeed even their own party. The Tea Party movement supplanted neoconservatism dominance over the Republican Party and those still clinging on for dear life are being cleared out by the new America First aligned Republicans who wish to supplant the war-hawks and globalists with non-interventionists and nationalists.

Conclusions

It is not radical nor unfair to say that not since the fall of the Berlin Wall has an ideological group lost its grip on power so completely as the neoconservatives have.

With the failure of nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan, the grotesque violation of individual liberties at home and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, neoconservatism, and indeed even the US government, became synonymous with warmongering, authoritarianism and out and out international crime. To quote Stephen Eric Bronner in his book Blood in the Sand:

“Like a spoiled child, unconcerned with what anyone else thinks, the United States has gotten into the habit of invading a nation, trashing it, and then leaving without cleaning up the mess.”

Neoconservatives like to hand-wring about the ‘evils’ of Middle Eastern dictators while they allow dogs to tear off the limbs of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, spy on innocent American citizens and bomb Afghani schools full of children into oblivion. Thanks to the neoconservative project of the early to mid-2000s – elements of which still are in place today – the United States became a leviathan monstrosity of surveillance, torture, corruption and warmongering.

It is interesting to see that after being the “cause célèbre of international politics”, neoconservatives are now the frequent targets of ridicule and scorn. And deservedly so, especially considering what neoconservatism has devolved into. The Straussian and genuinely conservative elements of the political philosophy have been ripped out, replaced with vague appeals to liberal humanitarianism and cucking for globalist organisations like the UN and NATO. The caricature of neoconservatives wanting drag queens to be able to use gender-neutral bathrooms at McDonalds in Kabul has shown to be somewhat accurate. After all, neoconservatives exist to promote ‘Western values’ in foreign countries, so naturally what they will end up promoting is the current cultural orthodoxy of progressive leftism, intersectionality and social decadence. An orthodoxy I’m sure Middle Easterners are desperately clamouring for.

However, despite their dwindling ranks and watering down of the ideology, the essence of neoconservative foreign policy remains intact; they still think the world should look like the United States. Therefore, it is unsurprising to see neoconservatives calling for every country in the world to be a liberal democracy along with the American model, or for Western troops to stay in Afghanistan indefinitely. Not only are these convictions still deeply held but are a direct expression of wanting American global hegemony to persist. On a deeper level, the recent pearl-clutching and whining from neoconservatives about the whole ordeal is simply a reflection of the anxiety that they now hold. Their ideas about what the world should look like have come collapsing before their eyes. And they can’t bear to face the fact that they were wrong.

This collapse has been occurring for some time and hopefully with the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, and the recent moves amongst elements of the right and left to adopt a more non-interventionist approach to foreign policy, the collapse of neoconservatism will remain permanent. After all, the neoconservatives who backed President Joe Biden – thinking he would spell a revival in their views – have now had an egg thrown in their face. Biden has proven himself to not be aligned with neoconservative foreign policy views.

Despite his claims that ‘America was back’ and his past support of foreign interventionism, it is evident that Biden has no real ideological attachment to staying in Afghanistan. In turn, he seems to have found it relatively easy to pull out and then spout rhetoric that wouldn’t be uncommon to hear at a Ron Paul rally. He stood against nation-building, turning Afghanistan into a unified centralised democracy and rejected endless military deployments and wars as the main tool of US foreign policy. Biden, alongside President Donald Trump, has turned the tide of US foreign policy away from military interventionism and back towards diplomacy. A surprise to be sure, but a welcome one.

However, while the ‘War on Terror’ may firmly be at an end – the American state has worryingly turned its eyes towards a new ‘War on Domestic Terror’. A war that political scientist and terrorism expert Max Abrahams worries will be catastrophic for the United States, quoting Abrahams: