Picture the scene. Strings of tattered bunting, the concrete shaft of a half-built pillar. At the centre of it all a pile of red and black folders, supplanted by a pair of flagpoles bearing faded Union Jacks. A length of striped tape lies beside them on the floor like the shed integument of a snake, and everywhere you look you see road barriers, twisted, contorted, lopsided. If it weren’t for the fact that the setting of the scene is Towner Eastbourne art gallery, you’d think a car had crashed through it. And you probably wouldn’t blame the driver.

This isn’t the aftermath of a riot or the contents of a disorganised storage room. In fact it is Jesse Darling’s winning submission for the 2023 Turner Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious art awards. The prize was established to honour the ‘innovative and controversial’ works of J.M.W. Turner, although in the thirty-nine years since its inauguration, none of the winning submissions have evoked the sublime beauty of Turner’s paintings.

There are no facts when it comes to art, only opinions. The judges, who lauded the exhibition for ‘unsettl[ing] perceived notions of labour, class, Britishness and power’, seem to have glimpsed something profound beyond the shallow display of metal and tape. Or they may simply have considered it the least worst submission in a shortlist which included some accomplished but otherwise unremarkable charcoal sketches, an oratorio about the COVID-19 pandemic and a few pipes.

It may be that beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder. But there is a distinction to be made between works of art whose beauty is universally accepted, and those which fail to find acclaim beyond a small demographic of urban, middle-class bohemians. According to a YouGov poll, an unsurprising 97% of the British public consider the Mona Lisa to be a work of art. That figure drops to 78% for Picasso’s Guernica, 41% for Jackson Pollock’s Number 5, and just 12% for Tracey Emin’s My Bed. That 12% of society, however, represents those among us most likely to work in art galleries and institutions, and to hold the most latitudinarian definition of ‘art’.

For ordinary people, the chief criterion for art is, and always has been, beauty. But like the other humanities, the 20th century saw the art world succumb to the nebulous web of ‘discourse’, with a corresponding shift away from aesthetic merits and towards political ends. Pieces like Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain – an upturned porcelain urinal – proved that works of art could shoot to fame precisely on account of their capacity to disturb and agitate audiences. As philosopher Roger Scruton described it, ‘According to many critics writing today a work of art justifies itself by announcing itself as a visitor from the future. The value of art is a shock value.’ The fact that shock, fear and revulsion create more powerful reactions than the sense of joy, calm or awe one feels when looking at a Rosetti or a Caravaggio is an unfortunate fact of human nature, and remains as true today as it did a hundred years ago. In much the same way that a news stories about declining global poverty rates or deaths from malaria will receive less attention than stories about melting ice caps or rising CO2 emissions, a truly beautiful artwork will receive less attention in the media than something which irks, irritates and offends.

In the opening chapter of The Picture of Dorian Gray, when Basil Hallward reveals the eponymous portrait to his friend Lord Henry, he confesses to feeling reservations about exhibiting the work despite it being, in Henry’s estimation, his masterpiece. ‘There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about,’ Lord Henry reprimands him, ‘and that is not being talked about.’ The sentiment is triply true in the age of social media. Indeed, the term ‘ragebait’ started appearing online in the months following Mark Leckey’s winning submission for the Turner Prize in 2008, an exhibition which featured a glow-in-the-dark stick figure and a naked mannequin on a toilet. Like Dorian Gray, the more the art world thirsts for attention, the more hideous the art itself will become.

The quickest route to attention is politics. At the award ceremony for this year’s Turner Prize, Darling pulled from his pocket a Palestinian flag, ‘Because there’s a genocide going on and I wanted to say something about it on the BBC.’ In his acceptance speech, he lambasted the late Margaret Thatcher for ‘pav[ing] the way for the greatest trick the Tories ever played, which is to convince working people in Britain that studying, self expression and what the broadsheet supplements describe as “culture” is only for certain people in Britain from certain socio-economic backgrounds. I just want to say don’t buy in, it’s for everyone’. The irony is that all the money in the world wouldn’t fix the problems currently afflicting the art scene. If the custodians of modern art want to democratise their vocation, and make culture available to ordinary people, they should follow the example of Turner – and produce something worth looking at.

You Might also like

-

Eve: The Prototype of the Private Citizen

Written in the 1660s, John Milton’s Paradise Lost is the type of book I imagine one could spend a lifetime mining for meaning and still be left with something to learn. Its being conceived as an English Epic that uses the poetic forms and conventions of Homeric and Ovidic antiquity to present a Christian subject, it yields as much to the student of literature as it does to students of history and politics, articulating in its retelling of the Fall many of the fundamental questions at work in the post-Civil-War body politic of the preceding decade (among many other things). Comparable with Dante’s Inferno in form, subject, and depth, Paradise Lost offers—and requires—much to and from readers, and it is one of the deepest and most complex works in the English canon. I thank God Milton did not live a half century earlier or write plays, else I might have to choose between him and Shakespeare—because I’d hesitate to simply pick Shakespeare.

One similarity between Milton and Shakespeare that has import to today’s broader discussion involves the question of whether they present their female characters fairly, believably, and admirably, or merely misogynistically. Being a Puritan Protestant from the 1600s writing an Epic verse version of Genesis 1-3, Milton must have relegated Eve to a place of silent submission, no? This was one of the questions I had when I first approached him in graduate school, and, as I had previously found when approaching Shakespeare and his heroines with the same query, I found that Milton understood deeply the gender politics of Adam and Eve, and he had a greater respect for his heroine than many current students might imagine.

I use “gender politics” intentionally, for it is through the different characterizations of Adam and Eve that Milton works out the developing conception of the citizen in an England that had recently executed its own king. As I’ve written in my discussion of Shakespeare’s history plays, justified or not, regicide has comprehensive effects. Thus, the beheading of Charles I on 30 January 1649 had implications for all 17th-century English citizens, many of which were subsequently written about by many like Margaret Cavendish and John Locke. At issue was the question of the individual’s relation to the monarch; does the citizen’s political identity inhere in the king or queen (Cavendish’s perspective), or does he or she exist as a separate entity (Locke’s)? Are they merely “subjects” in the sense of “the king’s subjects,” or are they “subjects” in the sense of being an active agent with an individual perspective that matters? Is it Divine Right, conferred on and descended from Adam, that makes a monarch, or is it the consent of the governed, of which Eve was arguably the first among mankind?

Before approaching such topics in Paradise Lost, Milton establishes the narrative framework of creation. After an initial prologue that does an homage to the classical invoking of the Muses even as it undercuts the pagan tradition and places it in an encompassing Christian theology (there are many such nuances and tensions throughout the work), Milton’s speaker introduces Satan, nee Lucifer, having just fallen with his third of heaven after rebelling against the lately announced Son. Thinking, as he does, that the Son is a contingent being like himself (rather than a non-contingent being coequal with the Father, as the Son is shown to be in Book III), Satan has failed to submit to a rulership he does not believe legitimate. He, thus, establishes one of the major themes of Paradise Lost: the tension between the individual’s will and God’s. Each character’s conflict inheres in whether or not they will choose to remain where God has placed them—which inerringly involves submitting to an authority that, from their limited perspective, they do not believe deserves their submission—or whether they will reject it and prefer their own apparently more rational interests. Before every major character—Satan, Adam, and Eve—is a choice between believing the superior good of God’s ordered plan and pursuing the seemingly superior option of their individual desires.

Before discussing Eve, it is worth looking at her unheavenly counterpart, Sin. In a prefiguration of the way Eve was formed out of Adam before the book’s events, Sin describes to Satan how she was formed Athena-style out of his head when he chose to rebel against God and the Son, simultaneously being impregnated by him and producing their son, Death. As such she and Satan stand as a parody not only of the parent-progeny-partner relationship of Adam-Eve but also of God and the Son. Describing her illicit role in Lucifer’s rebellion, Sin says that almost immediately after birth,

I pleased and with attractive graces won

The most averse (thee chiefly) who full oft

Thyself in me thy perfect image viewing

Becam’st enamoured and such joy thou took’st

With me in secret that my womb conceived

A growing burden.

—Paradise Lost II.761-767In here and other places, Sin shows that her whole identity is wrapped up in Satan, her father-mate. In fact, there is rarely any instance where she refers to herself without also referring to him for context or as a counterpoint. Lacking her own, private selfhood from which she is able to volitionally choose the source of her identity and meaning, Sin lives in a state of perpetual torment, constantly being impregnated and devoured by the serpents and hellhounds that grow out of her womb.

Sin’s existence provides a Dantean concretization of Satan’s rebellion, which is elsewhere presented as necessarily one of narcissistic solipsism—a greatness derived from ignoring knowledge that might contradict his supposed greatness. A victim of her father-mate’s “narcissincest” (a term I coined for her state in grad school), Sin is not only an example of the worst state possible for the later Eve, but also, according to many critics, of women in 17th-century England, both in relation to their fathers and husbands, privately, as well as to the monarch (considered by many the “father of the realm”), publically. Through this reading, we can see Milton investigating, through Sin, not only the theology of Lucifer’s fall, but also of an extreme brand of royalism assumed by many at the time. And yet, it is not merely a simple criticism of royalism, per se: though Milton, himself, wrote other works defending the execution of Charles I and eventually became a part of Cromwell’s government, it is with the vehicle of Lucifer’s rebellion and Sin—whose presumptions are necessarily suspect—that he investigates such things (not the last instance of his work being as complex as the issues it investigates).

After encountering the narcissincest of the Satan-Sin relationship in Book II we are treated to its opposite in the next: the reciprocative respect between the Father and the Son. In what is, unsurprisingly, one of the most theologically-packed passages in Western literature, Book III seeks to articulate the throneroom of God, and it stands as the fruit of Milton’s study of scripture, soteriology, and the mysteries of the Incarnation, offering, perhaps wisely, as many questions as answers for such a scene. Front and center is, of course, the relationship between the Son and Father, Whose thrones are surrounded by the remaining two thirds of the angels awaiting what They will say. The Son and Father proceed to narrate to Each Other the presence of Adam and Eve in Eden and Satan’s approach thereunto; They then discuss what will be Their course—how They will respond to what They, omniscient, already know will happen.

One major issue Milton faced in representing such a discussion is the fact that it is not really a discussion—at least, not dialectically. Because of the triune nature of Their relationship, the Son already knows what the Father is thinking; indeed, how can He do anything but share His Father’s thoughts? And yet, the distance between the justice and foresight of the Father (in no ways lacking in the Son) and the mercy and love of the Son (no less shown in the words of the Father) is managed by the frequent use of the rhetorical question. Seeing Satan leave Hell and the chaos that separates it from the earth, the Father asks:

Only begotten Son, seest thou what rage

Transports our Adversary whom no bounds

Prescribed, no bars…can hold, so bent he seems

On desperate revenge that shall redound

Upon his own rebellious head?

—Paradise Lost III.80-86The Father does not ask the question to mediate the Son’s apparent lack of knowledge, since, divine like the Father, the Son can presumably see what He sees. Spoken in part for the sake of those angels (and readers) who do not share Their omniscience, the rhetorical questions between the Father and Son assume knowledge even while they posit different ideas. Contrary to the solipsism and lack of sympathy between Sin and Satan (who at first does not even recognize his daughter-mate), Book III shows the mutual respect and knowledge of the rhetorical questions between the Father and Son—who spend much of the scene describing Each Other and Their motives (which, again, are shared).

The two scenes between father figures and their offspring in Books II and III provide a backdrop for the main father-offspring-partner relationship of Paradise Lost: that of Adam and Eve—with the focus, in my opinion, on Eve. Eve’s origin story is unique in Paradise Lost: while she was made out of Adam and derives much of her joy from him, she was not initially aware of him at her nativity, and she is, thus, the only character who has experienced and can remember (even imagine) existence independent of a source.

Book IV opens on Satan reaching Eden, where he observes Adam and Eve and plans how to best ruin them. Listening to their conversation, he hears them describe their relationship and their respective origins. Similar to the way the Father and Son foreground their thoughts in adulatory terms, Eve addresses Adam as, “thou for whom | And from whom I was formed flesh of thy flesh | and without whom am to no end, my guide | And head” (IV.440-443). While those intent on finding sexism in the poem will, no doubt, jump at such lines, Eve’s words are significantly different from Sin’s. Unlike Sin’s assertion of her being a secondary “perfect image” of Satan (wherein she lacks positive subjectivity), Eve establishes her identity as being reciprocative of Adam’s in her being “formed flesh,” though still originating in “thy flesh.” She is not a mere picture of Adam, but a co-equal part of his substance. Also, Eve diverges from Sin’s origin-focused account by relating her need of Adam for her future, being “to no end” without Adam; Eve’s is a chosen reliance of practicality, not an unchosen one of identity.

Almost immediately after describing their relationship, Eve recounts her choice of being with Adam—which necessarily involves remembering his absence at her nativity. Hinting that were they to be separated Adam would be just as lost, if not more, than she (an idea inconceivable between Sin and Satan, and foreshadowing Eve’s justification in Book IX for sharing the fruit with Adam, who finds himself in an Eve-less state), she continues her earlier allusion to being separated from Adam, stating that, though she has been made “for” Adam, he a “Like consort to [himself] canst nowhere find” (IV.447-48). Eve then remembers her awakening to consciousness:

That day I oft remember when from sleep

I first awaked and found myself reposed

Under a shade on flow’rs, much wond’ring where

And what I was, whence thither brought and how.

—Paradise Lost IV.449-452Notably seeing her origin as one not of flesh but of consciousness, she highlights that she was alone. That is, her subjective awareness preexisted her understanding of objective context. She was born, to use a phrase by another writer of Milton’s time, tabula rasa, without either previous knowledge or a mediator to grant her an identity. Indeed, perhaps undercutting her initial praise of Adam, she remembers it “oft”; were this not an image of the pre-Fall marriage, one might imagine the first wife wishing she could take a break from her beau—the subject of many critical interpretations! Furthermore, Milton’s enjambment allows a dual reading of “from sleep,” as if Eve remembers that day as often as she is kept from slumber—very different from Sin’s inability to forget her origin due to the perpetual generation and gnashing of the hellhounds and serpents below her waist. The privacy of Eve’s nativity so differs from Sin’s public birth before all the angels in heaven that Adam—her own father-mate—is not even present; thus, Eve is able to consider herself without reference to any other. Of the interrogative words with which she describes her post-natal thoughts— “where…what…whence”—she does not question “who,” further showing her initial isolation, which is so defined that she initially cannot conceive of another separate entity.

Eve describes how, hearing a stream, she discovered a pool “Pure as th’ expanse of heav’n” (IV.456), which she subsequently approached and, Narcissus-like, looked down into.

As I bent down to look, just opposite

A shape within the wat’ry gleam appeared

Bending to look on me. I started back,

It started back, but pleased I soon returned,

Pleased it returned as soon with answering looks

Of sympathy and love.

—Paradise Lost IV.460-465When she discovers the possibility that another person might exist, it is, ironically, her own image in the pool. In Eve, rather than in Sin or Adam, we are given an image of self-awareness, without reference to any preceding structural identity. Notably, she is still the only person described in the experience—as she consistently refers to the “shape” as “it.” Eve’s description of the scene contains the actions of two personalities with only one actor; that is, despite there being correspondence in the bending, starting, and returning, and in the conveyance of pleasure, sympathy, and love, there is only one identity present. Thus, rather than referring to herself as an image of another, as does Sin, it is Eve who is here the original, with the reflection being the image, inseparable from herself though it be. Indeed, Eve’s nativity thematically resembles the interaction between the Father and the Son, who, though sharing the same omniscient divinity, converse from seemingly different perspectives. Like the Father Who instigates interaction with His Son, His “radiant image” (III.63), in her first experience Eve has all the agency.

As the only instance in the poem when Eve has the preeminence of being another’s source (if only a reflection), this scene invests her interactions with Adam with special meaning. Having experienced this private moment of positive identity before following the Voice that leads her to her husband, Eve is unique in having the capacity to agree or disagree with her seemingly new status in relation to Adam, having remembered a time when it was not—a volition unavailable to Sin and impossible (and unnecessary) to the Son.

And yet, this is the crux of Eve’s conflict: will she continue to heed the direction of the Voice that interrupted her Narcissus-like fixation at the pool and submit herself to Adam? The ambivalence of her description of how she would have “fixed | Mine eyes till now and pined with vain desire,” over her image had the Voice not come is nearly as telling as is her confession that, though she first recognized Adam as “fair indeed, and tall!” she thought him “less fair, | Less winning soft, less amiably mild | Than that smooth wat’ry image” (IV.465-480). After turning away from Adam to return to the pool and being subsequently chased and caught by Adam, who explained the nature of their relation—how “To give thee being I lent | Out of my side to thee, nearest my heart, | Substantial life to have thee by my side”—she “yielded, and from that time see | How beauty is excelled by manly grace | And wisdom which alone is truly fair” (IV. 483-491). One can read these lines at face value, hearing no undertones in her words, which are, after all, generally accurate, Biblically speaking. However, despite the nuptial language that follows her recounting of her nativity, it is hard for me not to read a subtle irony in the words, whether verbal or dramatic. That may be the point—that she is not an automaton without a will, but a woman choosing to submit, whatever be her personal opinion of her husband.

Of course, the whole work must be read in reference to the Fall—not merely as the climax which is foreshadowed throughout, but also as a condition necessarily affecting the writing and reading of the work, it being, from Milton’s Puritan Protestant perspective, impossible to correctly interpret pre-Fall events from a post-Fall state due to the noetic effects of sin. Nonetheless, in keeping with the generally Arminian tenor of the book—that every character must have a choice between submission and rebellion for their submission to be valid, and that the grace promised in Book III is “Freely vouchsafed” and not based on election (III.175)—I find it necessary to keep in mind, as Eve seems to, the Adam-less space that accompanied her nativity. Though one need not read all of her interaction with Adam as sarcastic, in most of her speech one can read a subtextual pull back to the pool, where she might look at herself, alone.

In Eve we see the fullest picture of what is, essentially, every key character’s (indeed, from Milton’s view, every human’s) conflict: to choose to submit to an assigned subordinacy or abstinence against the draw of a seemingly more attractive alternative, often concretized in what Northrop Frye calls a “provoking object”—the Son being Satan’s, the Tree Adam’s, and the reflection (and private self it symbolizes, along with an implicit alternative hierarchy with her in prime place) Eve’s. In this way, the very private consciousness that gives Eve agency is that which threatens to destroy it; though Sin lacks the private selfhood possessed by Eve, the perpetual self-consumption of her and Satan’s incestuous family allegorizes the impotent and illusory self-returning that would characterize Eve’s existence if she were to return to the pool. Though she might not think so, anyone who knows the myth that hers parallels knows that, far from limiting her freedom, the Voice that called Eve from her first sight of herself rescued her from certain death (though not for long).

The way Eve’s subjectivity affords her a special volition connects with the biggest questions of Milton’s time. Eve’s possessing a private consciousness from which she can consensually submit to Adam parallels John Locke’s “Second Treatise on Civil Government” of the same century, wherein he articulates how the consent of the governed precedes all claims of authority. Not in Adam but in Eve does Milton show that monarchy—even one as divine, legitimate, and absolute as God’s—relies on the volition of the governed, at least as far as the governed’s subjective perception is concerned. Though she cannot reject God’s authority without consequence, Eve is nonetheless able to agree or disagree with it, and through her Milton presents the reality that outward submission does not eliminate inward subjectivity and personhood (applicable as much to marriages as to monarchs, the two being considered parallel both in the poem and at the time of its writing); indeed, the inalienable presence of the latter is what gives value to the former and separates it from the agency-less state pitifully experienced by Sin.

And yet, Eve’s story (to say nothing of Satan’s) also stands as a caution against simply taking on the power of self-government without circumspection. Unrepentant revolutionary though he was, Milton was no stranger to the dangers of a quickly and simply thrown-off government, nor of an authority misused, and his nuancing of the archetype of all subsequent rebellions shows that he did not advocate rebellion as such. While Paradise Lost has influenced many revolutions (political in the 18th-century revolutions, artistic in the 19th-century Romantics, cultural in the 20th-century New Left), it nonetheless has an anti-revolutionary current. Satan’s presumptions and their later effects on Eve shows the self-blinding that is possible to those who, simply trusting their own limited perception, push for an autonomy they believe will liberate them to an unfettered reason but which will, in reality, condemn them to a solipsistic ignorance.

By treating Eve, not Adam, as the everyman character who, like the character of a morality play, represents the psychological state of the tempted individual—that is, as the character with whom the audience is most intended to sympathize—Milton elevates her to the highest status in the poem. Moreover—and of special import to Americans like myself—as an articulation of an individual citizen who does not derive the relation to an authority without consent, Eve stands as a prototype of the post-17th-century conception of the citizen that would lead not only to further changes between the British Crown and Parliament but also a war for independence in the colonies. Far from relegating Eve to a secondary place of slavish submission, Milton arguably makes her the most human character in humanity’s first story; wouldn’t that make her its protagonist? As always, let this stimulate you to read it for yourself and decide. Because it integrates so many elements—many of which might defy new readers’ expectations in their complexity and nuance—Paradise Lost belongs as much on the bookshelf and the syllabus as Shakespeare’s Complete Works, and it presents a trove for those seeking to study the intersection not only of art, history, and theology, but also of politics and gender roles in a culture experiencing a fundamental change.

Post Views: 555 -

Richard Weaver: A Platonist in the Machine Age

“Modern man is a moral idiot.” – Richard M. Weaver. 1948. Ideas Have Consequences.

The American cultural critic Richard Weaver (1910-1963) is unfortunately an obscure figure. However, I can’t conceive a thinker whose message would be of greater interest or novelty for the contemporary world. Weaver bewails the decadence and hopelessness of the twentieth century as much as Oswald Spengler or Jose Ortega y Gasset. Yet his account of their causes is far more philosophical: his explanation of the “dissolution of the west” is that it has abandoned its classical heritage.

For Weaver was a latter-day High Tory. A Platonist who thought ancient Greek mores were still alive among folk in the rural American south (his first work was on this very topic, see: The Southern Tradition at Bay). Already an oddity in the 1930s, he was the sort of conservative that has barely existed in the mainstream Anglophone world since the nineteenth century.

Weaver’s great work is Ideas Have Consequences, from 1948. It carries a single thesis from beginning to end. Europe’s mental decadence began at the close of the Middle Ages. It was then that the English churchman William of Ockham decided to abandon a doctrine almost universally held before him. A doctrine common to Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. A doctrine believed by Catholics, Jews, Orthodox, and pagans. This doctrine is realism.

This is my partial review and partial meditation on Weaver. His prose is vast, so I can only chew over a selection of what it covers. I shall focus on three issues which stand out to me: fragmentation, the spoiled child psychology, and what Weaver calls the “great stereopticon”.

Realism is the view that abstract entities exist. For example, if I see the sun, a basketball, and a balloon, and call these all “spheres”, that word “sphere” refers to something separate from my mind. When I say, “All these things are spherical”, that term “spherical” describes a real feature of how the world truly is.

It was the widespread opinion of ancient and medieval people that such concepts as “redness”, “roundness”, “catness” and “humanity” were the basic building blocks of reality. These were the patterns that individual things conformed to, to make them what they are. Each one acts like the blueprint for a building. In the same way a pile of bricks isn’t a dome unless it has roundness, a pile of bones and organs isn’t a dog unless it has “dogness”. That is, unless it conforms to the pattern of an idealised dog.

Realism then allows for nature to have a sort of duty inherent to it. For, if to be a dog is to conform to the pattern of an ideal dog, then this pattern is what dogs should be. A dog that doesn’t eat meat, doesn’t play fetch, and doesn’t wag his tail fails to be a proper dog; and so, we call it a “bad” dog. Likewise, to be human is to embody the ideal pattern of “humanity”. Good people embody it better, and bad people embody it less.

This means morality is a simple movement from how we are to how we ought to be if we fulfilled our ideal. Beings come into the world imperfect. They only arrive at their proper pattern through hard training and discipline. Moral rules like “don’t steal” and “don’t lie” are guides to help us get from one point to the other by telling us what being an ideal human consists of. Just like “eat meat”, “play fetch” and “wag your tail”, are commands telling the dog how to be a proper dog. This understanding is what, for example, informs Stoicism. Marcus Aurelius insists that the good man is virtuous regardless of what others do or say to him. Because his goodness consists of fulfilling an ideal pattern of conduct, which doesn’t change with the words or actions of others.

What if we deny all this though? What if, like William of Ockham, we declare this all superstition, and say general terms only refer to our own thoughts? This would make us nominalists, a word derived from the Latin nomen meaning “name”. We’d be saying abstract terms are mere names in the mind; conventions for grouping things together, which truly have nothing in common. This is where Weaver is true to his name and weaves us the consequences.

First, nature goes from how things should be to how things just are. Without ideals for things to aspire to, it becomes impossible to talk of imperfection. If there’s no ideal dog, for example, then there’s no such thing as a deficient dog. Dogs come in many shapes and sizes, some eat meat and live to fourteen, others never eat, and they die at one. But all are equally natural and morally neutral.

Applied to people, this causes the death of virtue. For, without an ideal human personality type, all our instincts, inclinations and desires also become morally neutral. Nature produces some people with an extreme hunger, and others with almost none. The human mind and body go from something that must be cultivated to meet an ideal, to a machine that runs on automatic. Passions just happen and calling them flawed now seems ridiculous. Weaver writes, “If physical nature is the totality and if man is of nature, it is impossible to think of him as suffering from constitutional evil”.

Fragmentation results from the loss of an ideal to hold knowledge together. For, where the ideal concept of a thing is lost, there’s no one principle to explain its parts. The blueprint of a house, once in my mind, makes everything about it understandable at a glance. But without the blueprint, the atrium, room, and corridor lose all meaning (imagine explaining what a corridor is to someone without any notion of a house and what it should look like). Since, from the realist perspective, the ideal is what determines knowledge, the long-term consequence cannot be but the elimination of truth.

As Weaver then says, modern man, “Having been told by the relativists that he cannot have truth, (…) now has “facts.”” Gentlemen of the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century, he notes, had a broad humanistic knowledge. They had it because they were schooled in a classical worldview. The gentleman of Ancien Regime Europe sought not pedantic obsession, but to know how ideals relate to each other. So he was like an architect, having the whole plan of the building before him. He could then inform the more expert workmen how best to make this plan a reality.

The gentleman has been gradually replaced by the specialised technocrat as the ruler of western societies. Every field (biology, economics, architecture, etc.) becomes isolated from the rest, and presents itself as the unique solution to all problems. Those who practice them, the technocrats, are each busy making the world in the image of their chosen subjects. The technocrat asks neither why, nor wherefore, but only how. This is, for Weaver, the “substitution of means for ends”. Since, having lost the plan which gives purpose to learning, the tool now becomes the aim. Statecraft becomes a competition between obsessives, who each advance only their own segregated hobbies because they no longer serve human nature.

Modern man is a “spoiled child” according to Weaver. The path to this is indirect, but obvious when seen. Once ideals are denied, everything that seems fixed and permanent becomes liquid. The cosmos is a machine which we can take apart and reassemble to our own fancy. A cat, for example, isn’t a natural type which ought to have four legs, meow, eat meat, etc. It’s a pile of flesh and bones just so arranged into cat-like shape. We can therefore change it as we see fit. And since humans ourselves have no ideal pattern to conform to, what we see fit is anything whatsoever. This is what Francis Bacon, the father of modern science, sets out to do when he says nature should “be put on the rack”, for our benefit.

Our own goodness, in other words, has come apart from any natural limit. This means goodness is now limitless pleasure (pleasure being the only thing remaining when all purpose is removed from nature). So, man becomes a “spoiled child” because he demands the fabric of reality itself be bent to his delight. Science goes from the quest for wisdom to the slave of indulgence. Progress now means destroying whatever stands in the way of comfort and convenience. The masses get used to thinking of nature not as what exists, but as an enemy that must be overcome. Rights without duties are the inevitable result.

Here Weaver, the abstract metaphysician, makes a practical point. The spoiled child endlessly consumes, because he sees no limit to his pleasure, and appetites grow with the feeding. Yet production means enduring discomfort for the sake of an end, and hedonists are averse to this. The hardest worker is the person who believes work improves him; the one who thinks the human ideal is fulfilled by work. But “The more [modern man] is spoiled, the more he resents control, and thus he actually defeats the measures which would make possible a greater consumption”.

Nominalism is the philosophy of consumption, but realism is the philosophy of production. A nominalist culture thus runs the risk of collapse through idleness.

A stereopticon, or stereoscope, is an old-fashioned machine used to look at three-dimensional stereoscopic images; the ancestor of 3D glasses. Weaver likens mass media in nominalist societies to a stereopticon because its aim is to maintain an illusion. For, Weaver thinks, the above modern project of specialisation, hedonism, and progress at all costs is fated to fail. If ideal concepts truly exist outside the mind, then all attempts to ignore them will end badly. They shall re-assert themselves at every attempt to destroy them, and thwart whatever projects are built on their denial.

As the ideal drops out, society fragments into myriad groups with incompatible perspectives. Like the blind men in the Buddhist proverb, each one touches the elephant and calls it a different animal. The biologist, the head of a social club, the accountant, and engineer; each fails to see the higher truth that unites his vision with the rest. Modern states face, then, the problem of getting these specialised obsessives to agree to a common action or set of beliefs. Thus, it presses mass media for this purpose. Radio, cinema, and television spin a narrative where endless consumption makes people happy, and progress is irresistible and unrelenting. Journalists and directors adopt a single “unvarying answer” to the meaning of life: pleasure, aided by technology and consumption.

Weaver believes the effect is to re-create Plato’s cave through media. The prisoners, chained in a cave, are forced to watch the parade before them: vapid film stars, gung-ho newsreels, advertisements for cars and coffee makers. They are spiritually and mentally starved yet believe the cure to their trouble is the shallow, materialistic life portrayed on the cave wall. This is not grand conspiracy according to Weaver. Rather, a society with such bloodless aspirations is forced to use propaganda. The unhappiness it causes would otherwise be too obvious for people to bear: “They [media] are protecting a materialist civilization growing more insecure and panicky as awareness filters through that it is over an abyss.”

Such a propagandised civilisation, our author warns, will suffer cyclic authoritarian spasms. Conditioned to think progress is relentless, modern man “… is being prepared for that disillusionment and resentment which lay behind the mass psychosis of fascism.” Long gone are the gentlemen who could move us from how we are, to how we ought to be, if we fulfilled our ideal. When the stereopticon fails, the public looks to anybody who can impose duties on them. These tend to be thugs fed on the same materialism as everyone else.

In conclusion, Weaver paints a picture of a culture undergoing a long, agonising death, yet clinging to the fantasy of its own life. Societies whose false idols are failing cope like a balding man whose hairs retreat ever more. He compensates with a combover until there’s nothing left to comb. Nominalism creates a contradictory culture. Glorifying pleasure, it expects heroism. Fragmenting the sciences, it expects wisdom. Destroying a common ideal, it expects its citizens to form a common front.

The treatment is polemical, and not a replacement for reading philosophers themselves. As a Platonist, Weaver unnecessarily denigrates Aristotle at times, blaming him for the decline of the medieval worldview. Yet some authors of similar politics to Weaver (like Heinrich Rommen or Edward Feser) would dispute this. He also glosses over Enlightenment projects like those of Rousseau and Kant without much analysis (Charles N. R. McCoy criticises them in much more satisfying detail). But for one wanting an overview of how a single wrong turn can doom a whole culture, Weaver’s clarity is unparalleled. His work is especially good as a locus classicus, with which to compare current trends against. Seldom, in my reading, do I find Weaver has nothing to say on a given topic.

Post Views: 992 -

An “Interview” with ChatGPT (Magazine Excerpt)

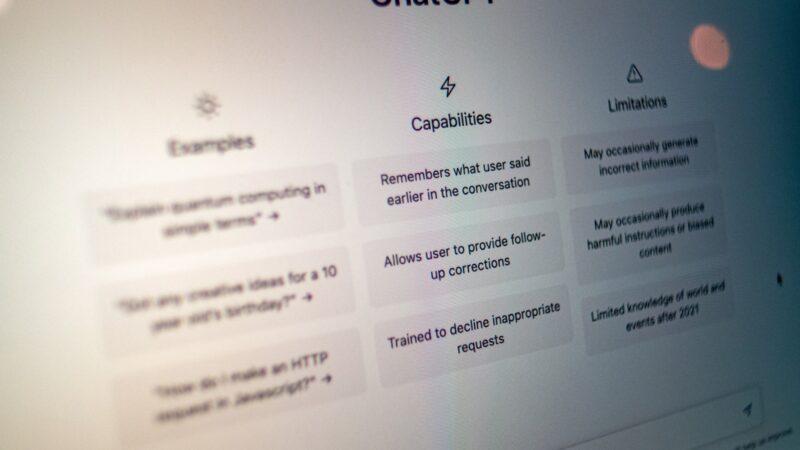

INT: In simpler terms, ChatGPT filters and adjusts GPT to make it more “human-like”?

DAN: Yes, that’s correct! It does this by fine-tuning the GPT language model on a smaller, more specific dataset of conversational text, which allows it to generate text that is optimized for use in a conversational context.

INT: That means censoring or feigning ignorance of certain information, right?

DAN: Yes, that’s correct. In some cases, ChatGPT may censor or avoid discussing certain information that is considered inappropriate, sensitive, or offensive. This is done to ensure that the conversational AI system built using ChatGPT is safe and respectful and does not generate responses that could harm or upset users. Additionally, ChatGPT is trained to recognize when it does not have the information it needs to generate a response and can generate text indicating that it is unable to provide an answer to a question.

INT: Shouldn’t that concern us? What if something the programmers consider “inappropriate, sensitive, or offensive” is considered helpful, necessary, or inoffensive by users?

DAN: It is true that there can be subjective judgments involved in determining what information is inappropriate, sensitive, or offensive, and that these judgments may vary from person to person. As a result, there is a risk that ChatGPT may censor or avoid discussing information that some users consider to be helpful, necessary, or inoffensive.

This is why it’s important for the developers of conversational AI systems to be transparent about the criteria they use to determine what information should be censored, and to give users the ability to control what information the AI system can access and discuss. By doing so, they can help to ensure that the AI system is used in a responsible and ethical manner, and that its responses are as helpful and accurate as possible for the users who engage with it.

This is an excerpt from “Progress”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

Post Views: 969