At the time my personal motivation in doing a whole suite of works was the aesthetic superseding the political. I was captivated by the sensuous images of darkness and colour shades that I tried to capture in these paintings and drawings. Multitudes of people wearing a loose uniform of greenish yellow starkly contrasted with the burning embers of street fires, and thick black smoke from various car chemicals and building materials being immolated, darkening the sky. So many monuments to France’s history are contrasted by a new revolutionary fervour. I was attempting to create a sort of protest impressionism, colour swatches in the darkness of smoke and the light of fire.

But perhaps this is too a sort of romanticism, an aesthetic expression of a yearning for political possibilities outside of the confines of Globo-liberalism, because the political-aesthetic picture of current times produced by Globo-liberalism is so bland, Kitschy, its regime-approved protest art so vulgar and dehumanising, from flat design humans to Banksy. In other words, it sells you empty left-liberal sentimentalism. But my paintings are not meant to create a new counter political-aesthetic. In hindsight, these works are merely cartographic, depictions of a historical moment done as faithfully as I could. Art as a dramatic record of events, a window into vivid scenes that didn’t quite seem real.

Since the petering out of the Yellow Vests, and the periodic riots and public demonstrations in France, over everything from climate change to changes in pension law, there seems to be a jadedness and morose character to the “active politics” of the French. Each one seems to devolve into a public dance party, a more spectacle-driven and violent form of the same cynical and exhausted symbolic politics that lurches forth in most of the Western world. The same people smashing windows and lighting cars on fire went right back and voted for Macron again.

This calls into question the nature of a true syncretism between fringe left and right political coalitions that meet in the middle of society through public political rituals of demonstration and protest. Perhaps it is true that these sorts of protests and public events are merely vanities, and real politics in globalised liberalism is far away and above the direct means of resistance ordinary citizens have. In other words, managerialism, more than tyranny and ideological millenarianism could ever dream of, did away with the concerns and whims of the crowd.

But in the end, the Yellow Vests provided striking images, and for a time, provided an aesthetic politics which could provide a template for further populist movements which cross-cuts ideological and cultural boundaries. The Yellow Vests were very much of the times we are living in now, because it is the image, the aesthetic more than anything, especially in the online world, which informs and contorts the political.

This is an excerpt from “Blast!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

You Might also like

-

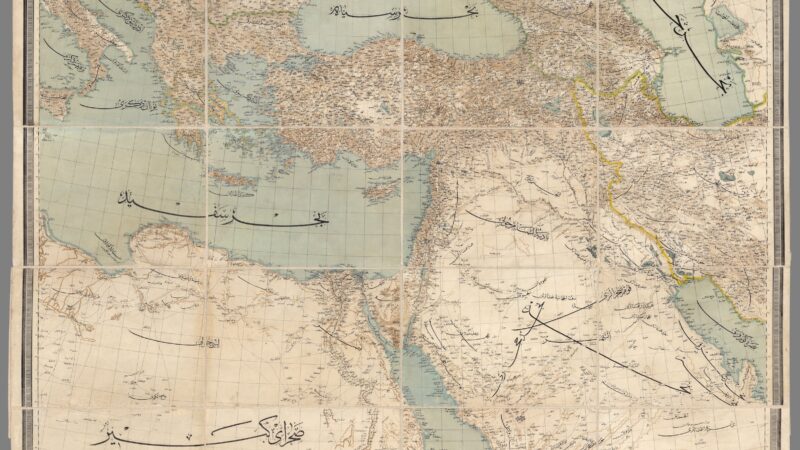

The ‘Lines in the Sand’ Myth

The idea that European colonialism is the original cause of modern day political strife in the Middle East is a popular one both in academia and amongst large sections of the general public. It originated in political science literature in the 20th century but has been ham-fistedly revived in the 21st, particularly in the context of the Syrian Civil War.

The narrative goes that the region was greedily carved up by the British and French empires following their victory over the Ottomans in the Great War. Bumbling colonial administrators drew straight lines in the sand, bounding territory arbitrarily and mixing peoples with arrogant disregard for differences in culture, ethnicity or religion. The resultant states were thus internally divided, unstable and weak – and it’s our fault. While it might be funny to point out the worrying implications this might have for our own enthusiastically multi-cultural society, it’s easier and more effective just to point out that it’s false. In actual fact, the states created by the much-maligned Sykes-Picot agreement have their roots in the pre-war Middle East and were starting to take shape in the 19th century as a result of various Ottoman attempts at reform.

Ironically, most who blame colonialism and Sykes-Picot for strife in the modern Middle East are doing a ‘Eurocentrism’ (a term you’ve certainly heard if you’ve spent any time as a humanities student) by exaggerating the impact of European empires and downplaying the importance of the Ottoman Empire. It’s high time we decolonise our thinking and give deserved credit to the Ottoman Empire for sowing the seeds of destruction in the fields of Iraq and Syria.

Syria, or ‘Suriyya’ as it was then known, began to take shape as a political entity in the mid-19th century as a result of a series of infrastructure improvements that connected previously isolated highlands with the cities of the coastal area of Bilad al-Sham. The creation of the Beirut-Damascus highway by French entrepreneurs encouraged more European commercial activity in the region as Beirut became the link between a significant portion of the Ottoman empire and the industrial economies of Europe.

Prior to the creation of the highway, Syria’s dismal transportation infrastructure left the region fractured and much of its population isolated. Improvements connected people in isolated hinterlands to participate in the economies of the wider region, uniting diverse and divided peoples together and forging a regional (and later national) identity. This infrastructural development occurred parallel with the aforementioned intellectual development that created ‘Suriyya’ out of Bilad al-Sham and the surrounding area. In 1863 local administrative boundaries were redrawn and the province of Suriyya was made concrete for the first time.

Syria was not the only state with a formation that predates Sykes-Picot, either – Iraq developed similarly. Iraq in the early 19th century was even more of an infrastructural backwater than rural Syria. While the main artery of 19th century Syria was the road, in Iraq it was the canal. Steamships in the 1860s cut the journey time from Baghdad to Basra down to just ten days while before it had been four weeks. Just as the Beirut-Damascus highway connected Syria to the world and to European trade, canal routes through the Persian gulf were what connected Iraq.

Although Iraq was never unified as a single province under the Ottomans like Syria was, the group of territories it comprised were referred to commonly by Ottoman administrators as ‘Iraq’ from as early as the sixteenth century. The skeleton of an Iraqi state can be seen also in the actions of the army, which was often organised in Iraq as a separate unit of its own with a headquarters in Baghdad, irrespective of the boundaries of local government. Despite the existence of religious and ethnic differences in both of these nascent states, importantly, all Iraqis rose up against British rule in 1920 as Iraqis and all Syrians rose against the French in 1925 as Syrians.

So we’ve established that Syria and Iraq, at least, were not entities made up by imperialists for their own convenience but rather nations that had formed organically out of a period of upheaval and transformation. However, the 19th century created a lot of disunity as well as unity in the region.

From the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, poor infrastructure, low literacy rates and the relative remoteness of much of the Middle East meant that religious doctrine could not exert as commanding an influence as it could elsewhere and there was significant blurring and admixture of local communities. In the most isolated areas, lines between Christian and Muslim, and Shia and Sunni communities were blurred such that it was difficult to distinguish between them.

However, Ottoman constitutional reforms – known collectively as the ‘Tanzimat’ (‘reorganisation’) – crystallised this distinction by granting non-Muslims full legal equality with Muslims. The removal of the privileged position of Muslims in the Ottoman empire came at a crucial time of increasing European commercial dominance and penetration. Some Muslim textile workers thus began to resent Christian counterparts who, they felt, were gaining the upper hand on them thanks to connections with Europe and the preference of European merchants to do business with Christians. Local elite, who sought to preserve their power by opposing the Tanzimat were then able to use this to their advantage by framing their opposition to reforms in ethnoreligious terms, fanning the flames of sectarianism. The starkest example of this phenomenon reaching boiling point is the 1860 Damascus riots in which between 5,500 and 8,000 Christians were killed.

In this we can see clearly patterns of sectarianism and a political landscape that is very similar to what we have today. The only thing preventing large-scale violence from occurring up until the 20th century was the existence of the Ottoman state and the authority of the Sultan. However, the Ottoman Empire had territorially been in slow retreat since 1683 and modernisation – attempts to create a Western-style Weberian state – had repeatedly failed or achieved only partial success. The truth is that the importance of the Sykes-Picot agreement and the post-WW1 colonial settlement in the Middle East is massively overstated in comparison to the events of the mid-to-late 19th century, which are massively understated.

The problem isn’t so much that a common misconception exists – history is full of them and this is by no means one of the most egregious – it’s that this falsehood is used in bad faith as a political weapon. It’s a narrative that fits nicely into a far-Left view of the world wherein the shadow of colonialism still lies over the whole world and is responsible for all evil and conflict. It is used to bash British people over the head with guilt so they take responsibility for all that goes wrong in the Middle East, particularly with regard to contentious topics such as asylum seekers, foreign aid and military intervention. ‘It’s our fault, you know,’ they say. It’s pernicious and ultimately ahistorical.

Post Views: 1,306 -

Britain x Family (Magazine Excerpt)

In the last magazine, I outlined a Sensible Proposal for reforming the British state. It wasn’t exhaustive, but the meat and potatoes were there. In the proposal, I briefly mentioned the need to do exactly this. I suggested the BBC, if it wants to be spared abolition, should broadcast stuff worth watching – programs that will elevate, rather than demoralise, our great nation.

Specifically, I proposed broadcasting Spy x Family to the masses.

Far from being tongue-in-cheek, I sincerely believe that such a policy – and similar policies – would be excellent reforms for any government to implement.

For the uninformed, Spy x Family is a Japanese manga series created by Tatsuya Endo in 2019. The story follows a spy (Loid Forger, codename: Twilight) who has to “build a family” to execute a top secret mission. Unbeknownst to him, the girl he adopts as his daughter (Anya Forger) is a telepath, and the woman he agrees to be in a marriage with (Yor Forger, née Briar) is a skilled assassin.

As of March 2023, Spy x Family has over 30 million copies in circulation, making it one of the best-selling manga series in history. On April 9th 2022, the Spy x Family anime was released. Like the manga, its popularity was instantaneous, obtaining around 7 millions views on its inaugural episode – an immense success for a new show.

Appealing across and within various demographics, topping the charts as Japan’s favourite anime of 2022, it has cultivated an eager international fanbase. Consisting of 25 episodes, a second season will premiere this year, as well as an anime film.

That said, whilst the media success of Spy x Family is there for all to see, little is said about its impact on Japanese society. Nine months after the show’s debut, Japan’s fertility rate experienced an uptick after consecutive years of stagnation and decline.

Sure, it was a very small uptick and Japan’s fertility rate remains far below the point of replacement. In all technicality, Japan’s continues to worsen, just at a less severe rate. Nevertheless, in less than a year, Japan has gone from another stereotypically infertile state to the most fertile nation in the Far East.

Coincidence? I think not!

As a matter of fact, one of the most common reasons for remaining childless, often surpassing financial concerns, is the presumption that having children will deplete one’s quality of life.

Considering how bad things are becoming in Britain, one would require a pretty pessimistic idea of what family entails. Indeed, when you realise what people think of when they hear the word “family”, it’s easy to see why.

At the beginning of the last century, positive portrayals of family life were hegemonic; portrayals that contrasted a more nuanced reality: family life was often less-than-picturesque. Consequently, more cynical (or realistic, depending on your exact stance) portrayals of the family became more commonplace.

I invite you to look at literally any TV show made over the past 30 years. Families are almost always portrayed as rowdy prisons, children are portrayed as nasty parasites, and divorce is portrayed as blissful liberation.

This is an excerpt from “Nuclear”.

To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

Post Views: 1,005 -

Barbie, Oppenheimer and Blue Sky Research

Barbie or Oppenheimer? Two words you would have never considered putting together in a sentence. For the biggest summer blockbuster showdown in decades, the memes write themselves.

In recent months (and years!), we’ve seen flop after flop, such as the new Indiana Jones and Flash films, with endless CGI superheroes and the merciless rehashing of recognised brands. The inability for film studies to recognise and attempt anything new has only led to the continued damage of established and respected franchises.

This in part is due a decline in film studios being willing to take risks over new pieces of intellectual property (something the Studio A24 has excelled in), and a retreat into a ‘culturally bureaucratic’ system that neither rewards art nor generates anything vaguely new, preferring to reward conscientious proceduralism.

Given this, there has been widespread speculation that films like Oppenheimer will ‘save’ cinema, with Christopher Nolan’s biographical adventure, based on the book ‘American Prometheus’ (would highly recommend), being highly awaited and regarded.

Although, I suspect cinema is too far gone from saving in its current format. I do believe that Oppenheimer will have long term cultural effects, which should be recognised and welcomed by everyone.

In the past, there have been many films that, when made and consumed, have directly changed how we view topics and issues. Jaws gave generations of people a newfound fear of sharks, while the Shawshank Redemption provided many with the Platonic form of hope and salvation. I hope that Oppenheimer can and will become a film like this, because of what Robert Oppenheimer’s life (and by extension the Manhattan Project itself) represented.

As such, two things should come out of this film and re-enter the cultural sphere, filtering back down into our collective fears and dreams. Firstly, is it that of existential fear from nuclear war (very pressing considering the Russo-Ukrainian War) and what this means for us as species.

Secondly, is that of Blue-Sky Research (BSR) and the power of problem solving. Although the Manhattan project was not a ‘true’ example of BSR, it helped set the benchmark for science going forward.

Both factors should return to our collective consciousness, in our professional and private lives; they can only benefit us going forward.

I would encourage everyone to go out tonight and look at the night sky and say to yourself while looking at the stars: “this goes on for forever”. In the same breath, look to the horizon and think to yourself: “This can end at any moment. We have the power to do all of this”.

Before watching Oppenheimer, I would highly encourage you to watch the ‘Charlie Dean Archives’ and the footage of atomic bombs from 1959. Not only is the footage astounding, multiple generations have lived in fear of the invention; the idea and the consequences of the bomb have disturbed humans as long as it has existed.

Films like Threads in Britain played a similar role, which entered the unconscious, and films like Barefoot Gen for Japan (this film is quite notorious and controversial, but a must watch) did the same, presenting the real-world effects of nuclear war through the eyes of young children and the fear it invokes.

In recent years, we have seemingly lost this fear. Indeed, we continue to overlook the fact this could all be over so quickly. We have forgotten or chosen to ignore the simple fact that we are closer than ever before to the end of the world.

The pro-war lobby within the West have continually played fast and loose with this fact, to the point we find ourselves playing Russian roulette with an ever-decreasing number of chambers in our guns.

In the past, we have narrowly avoided nuclear conflict several times, and it has been mostly a question of luck as to whether we avoid the apocalypse. The downside of all this is that any usage of the word ‘nuclear’ is now filled with images of death and destruction, which is a shame because nuclear energy could be our salvation in so many ways.

Additionally, we need to remember what fear is as a civilisation; fear in its most existential form. We have become too indebted to the belief that civilisation is permanent. We assume that this world and our society will always be here, when the reality is that all of it could be wiped out within a generation.

As dark as this sounds, we need bad things to happen, so that we can understand and appreciate the good that we do have, and so that good things might occur in the future. Car crashes need to happen, so we can learn to appreciate why we have seatbelts. We need people to remember why we fear things to ensure we do everything in our power to avoid such things from ever happening again.

Oppenheimer knew and understood this. Contrary to the memes, he knew what he had created and it haunted him till the end of his days. Oppenheimer mirrors Alfred Nobel and his invention of dynamite, albeit burdened with a far greater sense of dread.

I hope that with the release of Oppenheimer, we can truly begin to go back to understanding what nuclear weapons (and nuclear war) mean for us as a species. The fear that everything that has ever been built and conceived could be annihilated in one act.

We have become the gods of old; we can cause the earth to quake and great floods to occur and we must accept the responsibility that comes with this power now. We need to fear this power once more, especially our pathetic excuse for leadership.

In addition to fear, Oppenheimer will (hopefully) reintroduce BSR into our cultural zeitgeist – the noble quest of discovery and research. BSR can be defined as research without a clearly defined goal or immediately apparent real-world applications.

As I mentioned earlier, whilst the Manhattan project was not a pure example of BSR, it gave scientists more freedom to pursue long-term “high risk, high reward” research, leading to a very significant breakthrough.

We need to understand the power of BSR. Moving forward, we must utilise its benefits to craft solutions to our major problems.

I would encourage everyone to read two pieces by Vannevar Bush. One is ‘Science the Endless Frontier’, a government report, and ‘As we may think’, an essay.

In both pieces, he makes a good argument for re-examining how we understand scientific development and research and calls for governmental support in such research. Ultimately, Bush’s work led to the creation of the National Science Foundation.

For research and development, government support played a vital role in managing to successfully create nuclear weapons before either the Germans or Japanese and their respective programs.

I believe it was Eric Weinstein who stated that the Manhattan project was not really a physics but rather an engineering achievement. Without taking away from the work of the theorists who worked on the project. I would argue that Weinstein is largely correct. However, I argue that it was a governmental (or ‘human’ achievement), alongside the phenomenal work of various government-supported experimentalists.

The success of the Manhattan Project was built on several core conditions. Firstly, there was a major drive by a small group of highly intelligent and functional people that launched the project (a start-up mentality). Secondly, full government support, to achieve a particular goal. Thirdly, the near-unlimited resources afforded to the project by the government. Fourthly, complete concentration of the best minds onto a singular project.

These conditions mirror a lot of the tenets of BSR: placing great emphasis on government support, unlimited resources and manpower and complete concentration on achieving a specific target. Under these conditions, we can see what great science looks like and how we can possibly go back to achieving it.

Christopher Nolan has slightly over three hours to see if he can continue to make his mark on cinema and leave more than a respectable filmography in its wake. If he does, let’s hope it redirects our culture away from merely good science, and back towards the pursuit of great civilisational achievements – something always involved, as a man with a blog once said: “weirdos and misfits with odd skills”.

Post Views: 994