This dictatorship of the present has been enabled by around thirty years of material abundance and relative peace following the conclusion to the Cold War. As John Keegan, the military historian put it, Britain and American can afford our universalist idealism and our fantasies of a benevolent world united and ameliorated through commerce, given our good geographical fortune of being separated from continents by bodies of water. We can forget that the tides of history have pulled whole cultures under in violence and war, instead indulging in an imagined progressive history, moving ever upwards towards ever greater enlightenment and prosperity.

Our leaders, if they deserve the name, have forgotten the lessons of history, because they do not know history. They do not know the fate of nations and peoples. They are ignorant of the importance of the landscape of the world and the moral landscape of the heart, and how the interplay between the two shapes the destinies of civilisation. It is not to engage in nostalgia for a vanished age that never existed to reckon with the fact that those who governed us in the past were well aware of life’s tragic nature, of the reality of necessity and the ultimate goal of the avoidance of anarchy, its own form of tyranny. Our leaders in the 19th and up to the mid-20th centuries had been baptised in the fires of historical experience and therefore knew that the maintenance of right order, in accordance with the good, true, and beautiful, was the precondition for any liberty. Utopian, romantic ideas of universal rights, spreading democracy and natural freedom were dangerous in their unbounded idealism, leading nations and government astray in the quest for moral perfection.

History never ended, in the sense Francis Fukuyama meant it. Hegel, and his disciple Alexander Kojeve, were both wrong in discerning a direction to human History that would see the creation of the perfect liberal democratic regime and state of being in our world. History is the story of the deeds men and women do and accomplishments achieved together as clans, tribes, cities, empires, and nations. It is a story that will only end at the end of all things. Awareness of the living past reminds us that our lives are part of the weave of time, stretching back across the years, our own lives and the actions we take adding the threads that continue into the future.

This is an excerpt from “Mayday! Mayday!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

You Might also like

-

Dawn of the Anglosphere | Boško Vuković

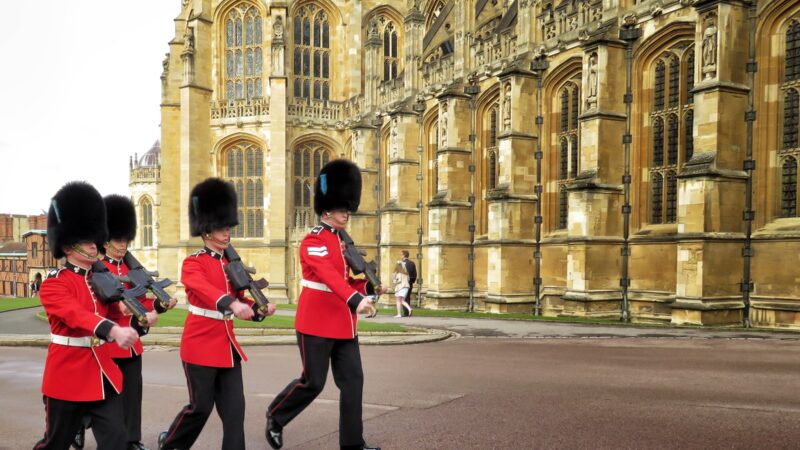

The Queen of Great Britain, Her Majesty Elisabeth II of the House of Windsor, has passed away. Her throne was inherited by her son, and heir, King Charles III of the House of Windsor. As one era ends, a new one dawns. And this new age for the United Kingdom, in essence, began in 2016 AD.

In 2016 AD, a referendum was held in the United Kingdom, one which would decide the fate of Great Britain, as well as Europe. The people of Albion voted to leave the European Union, a bureaucratized international organization which attempts to hold together the various nation-states of Europe. This moment was a historic one, for both Britain and Europe. Since Brexit, Europe is slowly transforming into a Franco-German union, as it naturally should be. Europe can, will and must follow its own historical destiny. The European Union, as it currently stands, may reform or break apart – but a new union will rise to take its place. In his book Imperialism: The Last Stage of Capitalism, the Russian revolutionary, Vladimir Lenin, foresaw, in passing, the creation of a Pan-European Bloc. On the other hand, the great British historian, Arnold J. Toynbee, declared that the next stage of Western Civilization is the Universal State. The European Union is one such state – or at least one of the first step towards it. The United States of America, on the other hand, also play the role of the Universal State in modern Western history, either as a true Universal Empire or its nucleus.

Then, an important question must be asked: what future awaits the people of Great Britain?

Now, when the United Kingdom has left the European Union, it certainly cannot, and will not, go back on its decision. It must not. On the other hand, the proud people of Albion cannot join the United States – and become one of its fifty federal states. Then where does Britain go from here?

There is only one sane decision to make – London must form a new bloc, a new international organization. An Anglosphere, if you will. Some may call it CANZUK. Others have named it as the Imperial Federation, a century ago. A political and economic union between Great Britain, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. This would either serve as Britain’s own attempt towards a Universal State, or yet another step towards a Western Imperium in the making. History will decide. But this Anglosphere would not only ensure the survival of Great Britain, but it would almost certainly guarantee its return as one of the Great Powers of the XXI century, rivaling the likes of the United States, the European Union, China, India and Russia.

Statistically speaking, it would be an enormous political entity. Its total area, somewhere around 18 million square kilometers, would place it as the world’s largest country. Its population of 136 million souls would place it right behind Russia, while its 7.6 trillion dollar GDP (nominal) would ensure its place as the world’s third largest economy, behind the likes of America and China. This new Great Power would possess one of the finest military forces in the modern world, reinforced with British nuclear weapons. Few would dare to challenge such a player of world politics.

Recent polls, carried out by CANZUK International – a think-tank dedicated to realizing such a union – show that the peoples of Australia (73% in favor), Canada (76% in favor), Great Britain (68% in favor) and New Zealand (82% in favor) would strongly support the formation of this quite unique bloc. These peoples share a common language, a common culture, an already integrated intelligence system, as well as a monarchic tradition. Such a move would cauterize the Quebecois as well as the Scottish independence movements, offering them broad autonomy, while maintaining their place within this grand Anglican confederation.

This idea, however, is not without its detractors.

Those on the Left would argue that this potential bloc would be a resurgent British Empire. This type of criticism is not without merit. For many peoples across the periphery of the Capitalist World-System the British Empire is synonymous with exploitation and colonialism. Rightly so, one might add. But the Left forgets one thing – for better (or worse in some rare cases), these countries are now independent nation-states, ready to carry on their own crosses and follow their own destinies, in this age of post-colonialism. Judging the sins of the British Empire is their job. Weighing its influence on their history is their duty. They must navigate the seas of fate on their own, and discover new possibilities for themselves. Thus, although one may criticize the excesses of the British Empire, the modern British man must not allow his judgment to be clouded by guilt. What is done is done. As the Winter Stage of Western History sets in, the people of Albion must look towards the future.

Others on the Left may argue that such a union would be a union of exclusively “white” peoples, excluding former British colonies such as India, South Africa or Nigeria. This argument is quite laughable, though. India, South Africa and Nigeria, as well as many other former British colonies, belong to different Cultures and Civilizations – while Great Britain, Canada, New Zealand and Australia are a part of Western Civilization.

For the heirs of Albion there can be no further discussion about this topic. The question is not about what is right or what is wrong – but what is necessary. The establishment of an Anglican Union should be the first, and foremost, goal of any rational British leader. And this goal, this ambition, should be endorsed by the Crown. Only then will the great nation of Britain reclaim its former glory, its last moment under the proverbial sun, in this Last Age of the West – before its inevitable end.

If His Majesty, King Charles III, alongside the British Government, decides to take this road towards the unification of the United Kingdom and its Daughters – he will go down in history as one of Britain’s greatest monarchs. As a connoisseur of Perennial Traditionalists, such as Rene Guenon, King Charles III knows what future awaits – not only the West, but the entire world as well. History has entrusted to Charles III a great Destiny.

Britannia must rule the waves – otherwise Britons shall become slaves. To whom it matters not.

The Hour of Decision grows near.

Time is of the essence.

Post Views: 1,084 -

Gaddafi: Existentialist, by Charlie Nash (Book Review)

Before I begin, I should note that I intended to write and publish this review much earlier. However, my “university” insisted that I do my “dissertation” because, apparently, it is “important” for my “degree” and “academic development”. Alas, my attempts at self-actualisation were crushed and I was reduced to another cog in the machine, from writer to institution. Sartre would have disapproved. Oh well.

Nash states that what started out as a tongue-in-cheek description of Gaddafi’s philosophy, founded on a handful of coincidences, evolved into an endless rabbit-hole of research. The result of this quasi-autistic spiral of pattern-recognition (I mean that in a good way) is Gaddafi: Existentialist.

Despite its short length (less than 100 pages), it is a structurally diverse work. So much so that the first chapter isn’t centred around Gaddafi or Existentialism (although, this is not arbitrary). Rather, it begins with one of Gaddafi’s inspirations: Colin Wilson.

As someone who has taken an interest in Colin Wilson’s life over the past few months (mainly: his origins as a literary outsider, his rise to prominence, and his association with The Angry Young Men) this work proved surprisingly useful in learning about Wilson, not just Gaddafi. Despite my own research thus far, I did not know that Wilson was invited to meet Gaddafi himself, or that Wilson’s works had received considerable popularity in the Middle East – “the largest existentialist scene outside of Europe”.

Indeed, the idea of a stout and bespectacled Colin Wilson, standing at the foot of a long red carpet with armed revolutionary socialists lining the way between him and his biggest fan: Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution of Libya Colonel Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, who eagerly clutches his personal copy of The Outsider in hopes of getting an autograph, is certainly an amusing one. Although, it seems that such a visit did not come to fruition. Sad!

As Nash notes, Gaddafi was something of an Outsider himself, both on the international stage as ruler of Libya and during his upbringing. A loner bookworm, he festered in his own idiosyncratic ideals of political revolution and societal renewal – “wow, he’s literally me!”. That said, Gaddafi’s core political philosophy (i.e., The Green Book) is not the primary focus of the work – although it is referenced. Rather, Nash centres on Gaddafi’s collection of short stories: Escape to Hell and Other Stories. Was anyone aware that Gaddafi wrote short stories? Regardless, it is interesting to see this neglected aspect of Gaddafi put under the microscope.

It is made evident to us that Gaddafi sees the city, as a reality and as an abstract concept, as an abomination – deracinating people from their organic identities, to be given new ones manufactured from crude necessity and economic convenience, depriving them of fruitful self-understanding and consequently inclining individuals towards nihilistic indifference. As one might suspect, for Gaddafi, the village embodies the preferable to all of this.

Using Gaddafi’s concern for the individual self, the way individuals construct their sense of self, rather than the internal machinations of a polity (of which economic maximization plays an important role), Nash quite effectively demonstrates that there is, at the very least, an existentialist component to Gaddafi’s worldview. However, it stands to reason that individual behaviour is not distinct from that which must be accounted for when running a polity. As such, whilst deciding to not focus on the overtly political, Nash’s insights won’t necessarily be redundant when discussing Gaddafi’s politics.

From death to authenticity, from freedom to self-understanding, Gaddafi’s short stories consistently delve into existentialist themes. Beyond the overarching argument itself, Nash’s humorously nonchalant summary of Gaddafi’s “most overtly existentialist text” – ‘The Suicide of an Astronaut’ – serves as an effective invitation to seek out and read the short stories in your own time:

“…A peasant asks the astronaut what he knows about tilling the earth, the astronaut responds with a lengthy monologue, reciting his vast scientific knowledge of the planet, its gravity, its size, and its distance from other planets.

As you can see, I am well informed in matters concerning the Earth, he boasts to the silent, bewildered peasant, who feels sorry for the ‘pathetic’ astronaut and leaves… The astronaut proceeds to commit suicide”.

Additionally, more than outline of Gaddafi’s relationship to existentialism, perhaps Nash’s book can help explain why some on the dissident right have become so infatuated with Third Worldist, Third Positionist political ideologies of religion-inspired socialism and nationalism as a potential response to the “Demonic Hell World” ushered in by modernity (see ‘Wholesome Chungus’ for further details).

Perhaps Geoff Shullenburger is right, Gaddafi may be just as much of a crypto-romanticist as he is a crypto-existentialist. Given his lamentations about the encroachment of urbanity onto the idyllic pastures of village life, and the scourge of scientific-industrial revolution, perhaps ‘The Colonel’ should have invested in a copy of William Blake’s poems.

All this being said, Nash is prudent to note that Gaddafi would have rejected the ‘Existentialist’ label and attributed Bedouin culture and Islamic teaching as the main source(s) of his political outlook. However, this does not contradict Nash’s argument. Although Gaddafi was not a self-identified ‘Existentialist’, his preoccupation with the aforementioned themes, both in the context of state-building and personal fancy, inadvertently place him on the horizon of Existentialism. Readers may disagree with Nash’s interpretation of Gaddafi, but the willingness of the author to acknowledge the subject’s explicit and direct thoughts on the matter should reassure everyone that it is an honest analysis.

In summary, even if one doesn’t go in with expectations of being convinced of Gaddafi’s Existentialism, anti-Existentialism, or indifference thereto, it still holds up as an enjoyably niche work on the existential-ish outlook of one of the most idiosyncratic political leaders of the 21st century.

Photo Credit

Post Views: 1,292 -

Kemi Badenoch has changed the nature of Tory leadership contests forever

Many British conservatives look at America’s Republican Party with envy. They have a slate of talented potential candidates for the 2024 US general election, and what with increasing numbers of Hispanics and black Americans voting for the GOP, they are likely to triumph in this year’s midterm elections in the face of a crumbling Biden administration that has pandered to the left over trans and cultural issues. They are also confronting many other problems that have started to destroy America’s self-confidence such as critical race theory and Black Lives Matter. It is a good time to be an American conservative right now.

Compared to the Republicans, the British Conservative Party is like the black sheep of the Western conservative family. Anyone who did their research on Boris Johnson before he gained the highest office in the land, such as me, knew his time as prime minister would be short and full of scandal. Those who knew this Conservative leadership race was inevitable suspected that the selection of candidates to replace Boris would be underwhelming. But there was one person who changed this year’s Tory leadership election: Kemi Badenoch.

It was always unlikely that she was going to win. Kemi was an equalities minister, an unknown government position. Her profile was quite low before she entered the race. I have no doubt that she wanted to win the Tory leadership contest and implement the changes she talked about. However, arrogant Tory MPs thought they knew best and eliminated her. The truth is that she was too radical for them. Regardless, she has transformed Conservative leadership races forever.

The reason why I made a reference to the culture wars the Republicans are fighting in the US above is because the UK is facing the same issue, and whilst Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak were clashing over the best way to generate growth, Kemi was the only candidate to discuss the impact of political correctness on Britain. As Louise Perry wrote for The New Statesman, she is a black woman from Nigeria who is resistant to groupthink.

Perry further explains that it wasn’t the fact that Badenoch is a black conservative that distinguished her from her talentless rivals; it was because she demonstrated how wrong her critics are about the assumptions often made about ethnic minority individuals in politics. She does not succumb to groupthink on Black Lives Matter in Britain, which would have made her the perfect person to take on that group’s victimhood mentality. They believe black people are victims of institutional racism. Their influence over British politics has increased since the death of George Floyd, and whilst the gutless Keir Starmer bent the knee for Black Lives Matter, Badenoch never did. If she became leader of the Conservative Party and prime minister, she would have proved the UK does not have a problem when it comes to institutional racism.

Furthermore, Badenoch had a plan to deal with political correctness. She is against gender-neutral toilets and she is opposed to throwing money at staff wellbeing coordinators (whatever they are). Despite being an immigrant herself, she also pledged to end the illegal Channel crossings that Boris has failed to deal with. Badenoch said she would do ‘whatever it takes’ to tackle illegal immigration, and in my opinion, that is a huge hint that she would have eventually pulled the UK out of the European Convention of Human Rights that thwarted the recent Rwanda flights. She stood out as a woman of principle, unlike Penny Mordaunt who proved to be nothing more than a fraud by reversing her previous pro-trans positions.

As a result of her anti-PC stance, Badenoch enthused the Tory membership base. There were numerous ‘Back Badenoch’ hashtags on Conservative Party members’ Twitter profiles, which further disproves Black Lives Matter’s theory on institutional racism because a mostly white, middle-aged party was so excited about the prospect of a Nigerian black lady becoming Tory leader. Her ideas were music to their ears.

And it is no wonder they were so enthused by Badenoch’s ideas. As Frank Feudi wrote for Sp!ked, Boris’s record on tackling political correctness is dreadful. Whilst he remained opposed to trans ideology in principle, last October him and his wife Carrie attended a Stonewall event at Conservative Party Conference, an organisation that has done more than any other to impose trans ideas upon society. Tucker Carlson also claimed Boris’s failure was that he did not govern like Trump, who took a tough stance towards the culture wars throughout his presidency. Boris even said himself he did not want to engage in a culture war. It is no wonder his cowardice paved the way for excitement about Badenoch amongst Conservative activists.

The Conservative Party is heading for defeat in 2024. Though Labour might not win a majority, I cannot see either Truss or Sunak being able to reverse the damage Boris has inflicted upon the political system and this country. They have been in power for too long and the lack of originality from the two remaining leadership candidates shows they are out of ideas. Their best outcome before 2024 would be to lose to a Labour-led government, retain a reasonable number of seats so that they can win again in 2028 or 2029, and elect Badenoch to provide the Tories with some fresh thinking and new policy positions.

It is a relief to say that the Conservatives have finally found a refreshing new candidate with bold ideas. Nonetheless, it is a pity that out-of-touch Tory MPs felt that she was not leadership material this year, and that they knew better than their members who help them get elected. The Conservatives would be wise to at least provide Badenoch with a cabinet position. But for now, they have made a dreadful mistake and they deserve to lose in 2024. The Tories can only redeem themselves by electing Badenoch as leader in the aftermath of an embarrassing electoral defeat.

Post Views: 1,105