Culture is often a bearer of such practical wisdom. Indeed, the reason we listen to the experienced and wise, despite their lack of formal education, is that their experience has imparted practical wisdom. Theoretical wisdom is implicit in this down to earth practicality. Although the village elder might not be able to say why a certain behaviour is virtuous, her account, being correct, could be elaborated to reveal a true and natural principle. Extending this to an entire culture, we have one basis for social conservatism. The accumulated experience of ages has a sort of implicit wisdom to it, which can be potentially made into a theory, even though nobody may have yet done so. However, this isn’t enough, lest we be agnostic pragmatists like David Hume. For the one clinging to classical ideas, all practical wisdom has a theory behind it whose objective springs we can discover through reason.

One such cultural heirloom that is greatly misunderstood these days is aristocracy. Most cultures in human history have had aristocracies of some type. A noble class existed in ancient Mesopotamia, Persia, Mesoamerica, the Andes, Egypt, China, Japan, Greece, Rome, among the Celts, as well as mediaeval and early modern Europe. Indeed, aristocracy of some type has been one of the most common institutions of humanity across history. Yet in the last three hundred years, aristocracies have shrunk, from the predominant ruling elites of the world to disempowered and mocked cliques, clinging to privileges regarded as archaic.

Britain is one of the few countries that still has an institutional aristocracy. But its influence is ever diminishing, its numbers ever depleting, and its ideals waned to nothing. I doubt many would contradict me if I said its public image is far from positive. I believe the cause of this decline is that it is a remnant of a previous ethical outlook, one rooted in ancient Greek and Roman thought, and Christianised in the Middle Ages. This outlook collapsed in Britain during the eighteenth century (before it did in most of Europe). Whig liberal philosophers like John Locke chipped at its foundations. The aristocracy as a result became an institution without a purpose, embedded in a new society totally hostile to it.

So, what are these foundations? I think three: human goodness as function, a communitarian spirit, and a family-centred life. Really, it’s only the first, functional goodness, the latter two being elaborations of it.

Goodness as a function is simple. To be good is to function properly according to a species’ ideal. In the same way a good hammer is good at banging nails, and a good oven at baking bread, so a good human being is good at “human-ing” to coin a verb. The question ‘what is goodness?’ for ancient and mediaeval thinkers is almost invariably ‘what’s the function of humans?’ Yet because humans have reason, unlike animals who merely follow their instincts, our function involves more than survival and reproduction. We make art and science, and can appreciate the value of things through understanding. We are the animal that is happy with a garden and a library, as Cicero says.

This is an excerpt from “Mayday! Mayday!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

You Might also like

-

What is the Point of the Turner Prize?

Picture the scene. Strings of tattered bunting, the concrete shaft of a half-built pillar. At the centre of it all a pile of red and black folders, supplanted by a pair of flagpoles bearing faded Union Jacks. A length of striped tape lies beside them on the floor like the shed integument of a snake, and everywhere you look you see road barriers, twisted, contorted, lopsided. If it weren’t for the fact that the setting of the scene is Towner Eastbourne art gallery, you’d think a car had crashed through it. And you probably wouldn’t blame the driver.

This isn’t the aftermath of a riot or the contents of a disorganised storage room. In fact it is Jesse Darling’s winning submission for the 2023 Turner Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious art awards. The prize was established to honour the ‘innovative and controversial’ works of J.M.W. Turner, although in the thirty-nine years since its inauguration, none of the winning submissions have evoked the sublime beauty of Turner’s paintings.

There are no facts when it comes to art, only opinions. The judges, who lauded the exhibition for ‘unsettl[ing] perceived notions of labour, class, Britishness and power’, seem to have glimpsed something profound beyond the shallow display of metal and tape. Or they may simply have considered it the least worst submission in a shortlist which included some accomplished but otherwise unremarkable charcoal sketches, an oratorio about the COVID-19 pandemic and a few pipes.

It may be that beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder. But there is a distinction to be made between works of art whose beauty is universally accepted, and those which fail to find acclaim beyond a small demographic of urban, middle-class bohemians. According to a YouGov poll, an unsurprising 97% of the British public consider the Mona Lisa to be a work of art. That figure drops to 78% for Picasso’s Guernica, 41% for Jackson Pollock’s Number 5, and just 12% for Tracey Emin’s My Bed. That 12% of society, however, represents those among us most likely to work in art galleries and institutions, and to hold the most latitudinarian definition of ‘art’.

For ordinary people, the chief criterion for art is, and always has been, beauty. But like the other humanities, the 20th century saw the art world succumb to the nebulous web of ‘discourse’, with a corresponding shift away from aesthetic merits and towards political ends. Pieces like Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain – an upturned porcelain urinal – proved that works of art could shoot to fame precisely on account of their capacity to disturb and agitate audiences. As philosopher Roger Scruton described it, ‘According to many critics writing today a work of art justifies itself by announcing itself as a visitor from the future. The value of art is a shock value.’ The fact that shock, fear and revulsion create more powerful reactions than the sense of joy, calm or awe one feels when looking at a Rosetti or a Caravaggio is an unfortunate fact of human nature, and remains as true today as it did a hundred years ago. In much the same way that a news stories about declining global poverty rates or deaths from malaria will receive less attention than stories about melting ice caps or rising CO2 emissions, a truly beautiful artwork will receive less attention in the media than something which irks, irritates and offends.

In the opening chapter of The Picture of Dorian Gray, when Basil Hallward reveals the eponymous portrait to his friend Lord Henry, he confesses to feeling reservations about exhibiting the work despite it being, in Henry’s estimation, his masterpiece. ‘There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about,’ Lord Henry reprimands him, ‘and that is not being talked about.’ The sentiment is triply true in the age of social media. Indeed, the term ‘ragebait’ started appearing online in the months following Mark Leckey’s winning submission for the Turner Prize in 2008, an exhibition which featured a glow-in-the-dark stick figure and a naked mannequin on a toilet. Like Dorian Gray, the more the art world thirsts for attention, the more hideous the art itself will become.

The quickest route to attention is politics. At the award ceremony for this year’s Turner Prize, Darling pulled from his pocket a Palestinian flag, ‘Because there’s a genocide going on and I wanted to say something about it on the BBC.’ In his acceptance speech, he lambasted the late Margaret Thatcher for ‘pav[ing] the way for the greatest trick the Tories ever played, which is to convince working people in Britain that studying, self expression and what the broadsheet supplements describe as “culture” is only for certain people in Britain from certain socio-economic backgrounds. I just want to say don’t buy in, it’s for everyone’. The irony is that all the money in the world wouldn’t fix the problems currently afflicting the art scene. If the custodians of modern art want to democratise their vocation, and make culture available to ordinary people, they should follow the example of Turner – and produce something worth looking at.

Post Views: 683 -

Madness and Spectacle: The Yellow Vest Suite (Magazine Excerpt)

At the time my personal motivation in doing a whole suite of works was the aesthetic superseding the political. I was captivated by the sensuous images of darkness and colour shades that I tried to capture in these paintings and drawings. Multitudes of people wearing a loose uniform of greenish yellow starkly contrasted with the burning embers of street fires, and thick black smoke from various car chemicals and building materials being immolated, darkening the sky. So many monuments to France’s history are contrasted by a new revolutionary fervour. I was attempting to create a sort of protest impressionism, colour swatches in the darkness of smoke and the light of fire.

But perhaps this is too a sort of romanticism, an aesthetic expression of a yearning for political possibilities outside of the confines of Globo-liberalism, because the political-aesthetic picture of current times produced by Globo-liberalism is so bland, Kitschy, its regime-approved protest art so vulgar and dehumanising, from flat design humans to Banksy. In other words, it sells you empty left-liberal sentimentalism. But my paintings are not meant to create a new counter political-aesthetic. In hindsight, these works are merely cartographic, depictions of a historical moment done as faithfully as I could. Art as a dramatic record of events, a window into vivid scenes that didn’t quite seem real.

Since the petering out of the Yellow Vests, and the periodic riots and public demonstrations in France, over everything from climate change to changes in pension law, there seems to be a jadedness and morose character to the “active politics” of the French. Each one seems to devolve into a public dance party, a more spectacle-driven and violent form of the same cynical and exhausted symbolic politics that lurches forth in most of the Western world. The same people smashing windows and lighting cars on fire went right back and voted for Macron again.

This calls into question the nature of a true syncretism between fringe left and right political coalitions that meet in the middle of society through public political rituals of demonstration and protest. Perhaps it is true that these sorts of protests and public events are merely vanities, and real politics in globalised liberalism is far away and above the direct means of resistance ordinary citizens have. In other words, managerialism, more than tyranny and ideological millenarianism could ever dream of, did away with the concerns and whims of the crowd.

But in the end, the Yellow Vests provided striking images, and for a time, provided an aesthetic politics which could provide a template for further populist movements which cross-cuts ideological and cultural boundaries. The Yellow Vests were very much of the times we are living in now, because it is the image, the aesthetic more than anything, especially in the online world, which informs and contorts the political.

This is an excerpt from “Blast!”. To continue reading, visit The Mallard’s Shopify.

Post Views: 937 -

Liberalism and Planned Obsolescence

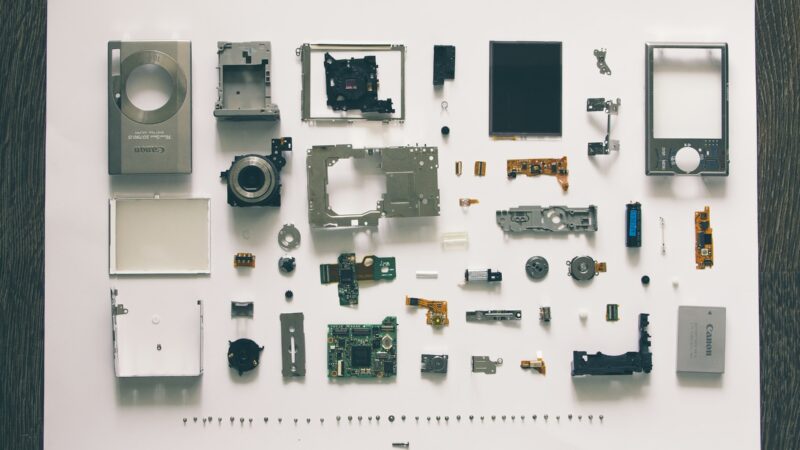

Virtually everyone at some point has complained about how their supposedly state-of-the-art phone, tablet, laptop, or computer doesn’t seem quite so cutting-edge when it either refuses to work properly or ceases to function entirely after a disappointingly brief period of time. This is not merely the grumblings of aggravated customers, but a consequence of “planned obsolescence.” The term dates back to the Great Depression, coined by Bernard London in his 1932 paper Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence, but a practically concise definition comes courtesy of Jeremy Bulow as “the production of goods with uneconomically short useful lives so that customers will have to make repeat purchases.” Despite being an acknowledged (and in some cases encouraged) practice, it is still condemned; both Apple and Samsung have faced legal action on multiple occasions for introducing software updates which actively hinder the performance of older devices. In the face of all this, planned obsolescence isn’t going anywhere so long as there is technology, nor does anyone expect it to. It is, as death and taxes are, one of the few certainties of life.

As the title of this essay suggests, I do not intend to delve any further into the technological or economic ethics of planned obsolescence. Interesting as they may be, I want to focus on how the concept appears in a political context; more specifically, in liberalism.

One of the core tenets of liberalism is a belief in the “Whig interpretation of history.” In his critique of the approach, aptly titled The Whig Interpretation of History, Herbert Butterfield outlined the Whig disposition as being liable to “praise revolutions provided they have been successful, to emphasize certain principles of progress in the past and to produce a story which is the ratification if not the glorification of the present.” To boil it down, it is the belief that history is a continuous march of progress, with each successive step freer and more enlightened than the last. A Whiggish liberal is dangerously optimistic in their opinion that history has led to the present being the greatest social, economic, and political circumstances one could hitherto be born into. More dangerous still is their restlessness, for as good as the present may be, it cannot rest on its laurels and must make haste in progressing even further such that the future will be even better. The pinnacle of human development lasts as long as a microwave cooking a spoon, receiving for its valiant effort little other than sparks, fire, and irreparable damage resulting in its subsequent replacement.

The unrepentant Whiggery of the modern world has prompted scholars of the Traditionalist School of philosophy to label it an aberration amongst all other societies, as the first which does not assign any inherent value to, or more accurately, openly detests, perennial wisdom (timeless knowledge passed down through generations) and abstract metaphysical truths. In the words of René Guénon, “the most conspicuous feature of the modern period [is its] need for ceaseless agitation, for unending change, and for ever-increasing speed.” Quite literally, nothing is sacred. One of the primary causes of this is that modernity, defined by its liberalism, is materialist, and believes that anything and everything can and should be explained rationally and scientifically within the physical world. The immaterial and the spiritual are disregarded as irrational, outmoded and unjustifiable; it is, as Max Weber says, “disenchanted.”

To understand this further, we must consider Plato’s conceptions of the two distinct natures of the spiritual and the material/physical world, “being” and “becoming” respectively. Being is constant and axiomatic, characterised by abstract ideas, timeless truths and stability. Becoming on the other hand, as the nature of the physical world, reflects the malleability of its inhabitants and exists in an endless state of flux. Consider your first car, it will alter with time, the bodywork might rust and you may need new parts for it, and indeed it may eventually be handed on to a new owner or even scrapped entirely. Regardless of what changes physically, its first car status can never be separated from it, not even when you no longer own it or it’s recycled into a fridge, for it will always hold a metaphysical character on a plane beyond the material.

Julius Evola, another Traditionalist scholar, succinctly defined a Traditional society as one where the “inferior realm” of becoming is subservient to the “superior realm” of being, such that the inherent instability of the former is tempered by orientation to a higher spiritual purpose through deference to the latter. A society of liberalism is unsurprisingly not Traditional, lacking any interest in the principles of being, and is instead an unconstrained force of pure becoming. Perhaps rather than disinterest, we can more accurately characterise the liberal disposition towards being as hostile. After all, it constitutes the “customs” which one of classical liberalism’s greatest philosophers, John Stuart Mill, regarded as “despotic” and a “hindrance to human development.” Anything which is perennial, traditional, or spiritual is deleterious to the march of progress unless it can either justify its existence within the narrow rubric of liberal rationalism, or abandon its traditional reference points and serve new masters. With this mindset, your first car doesn’t represent anything to do with the sense of both liberation and responsibility that comes with being able to transport yourself, it is simply a lump of metal to tide you over until you can get a more expensive lump of metal.

Of course, I do not advocate keeping a car until it falls to pieces, it is simply a metaphor for considering the abstract significance of things which may be obscured by their physical characteristics. In the real world, the stakes are much higher, where we aren’t just talking about old cars but long-standing cultural structures, community values and particularisms, and other such social authorities that fall victim to the ravenous hunger of liberal progressivism.

The consequence of this, as with all things telluric, material, or designed by human effort, is impermanence. Without reference to and deliberate denigration of being, ideas, concepts and structures formed within the liberal system have no permanent meaning; they are as fickle as the humans who constructed them. Roger Scruton eloquently surmised this conundrum when lambasting what he called the “religion of Rights”, whereby human rights, or indeed any concepts of becoming (without spiritual reference, or to being) are defined by subjective “moral opinions” and “legal precepts.” Indeed “if you ask what rights are human or fundamental you get a different answer depending whom you ask.” I would further add the proviso of when you ask, as a liberal of any given period appears to their successors as at best outdated or at worst reactionary. Plucking a liberal from 1961, 1981, 2001, and 2021, and sitting them around a table to discuss their beliefs would result in very little agreement. They may concur on non-descript notions of “freedom” and “equality”, but they would struggle to find congregate over a common understanding of them.

To surmise, any idea, concept or structure that exists within or is a product of liberalism is innately short-lived, as the ceaseless agitation of becoming necessitates its destruction in order to maintain the pace of the march of progress. But Actual people, regardless of how progressive or rational they claim to be, rarely keep up with this speed. They tend to follow Robert Conquest’s first law of politics: “everyone is conservative about what he knows best.” People are naturally defensive of the familiar; just as an aging iPhone slows down with time or when there’s a new update it can’t quite cope with, so too will liberals who fail to adapt to changing circumstances. Sadly for them, the progressive thirst of liberalism requires constant refreshment of eager foot-soldiers if its current flock cannot keep up, unafraid to put down any fallen comrades if they prove a liability, no matter how loyal or consequential they may have once been. Less, as Isaac Newton famously wrote, “standing on the shoulders of giants”, more “relentlessly slaying giants and standing on a pile of their fallen corpses”, which as far as I’m aware no one would ever outright admit to.

You don’t have to look particularly far to find recent examples of this. In the 1960s and 70s, John Cleese pioneered antinomian satire such as Monty Python and Fawlty Towers, specifically mocking religious and British sensibilities. Now, in response to his assertion that cultural and ethnic changes have rendered London “no longer English”, he is derided for being stuffy and racist. Indeed, Ken Livingstone, Boris Johnson, and Sadiq Khan, the three progressive men (in their own unique ways) who have served as Mayor of London since its establishment in 2000, lined up on separate occasions to attack Cleese, with Khan suggesting that the comments made him “sound like he’s in character as Basil Fawlty.” There is certainly a poetic irony in becoming the very thing you once satirised, or perhaps elegiac for the liberals who dug their own graves by tearing down the system, only to become the system and therefore a target of that same abuse at the hands of others.

Another example is George Galloway, a staunch socialist, pro-Palestinian, and unbending opponent of capitalism, war, and Tony Blair. Since 2016 however, he has come under fire from fellow leftists for supporting Brexit (notably, something that was their domain in the halcyon days of Tony Benn, Michael Foot, and Peter Shore) and for attacking woke liberal politics. Other fallen progressives include J. K. Rowling and Germaine Greer, feminists who went “full Karen” by virtue of being TERFs, and Richard Dawkins, one of New Atheism’s four horsemen, who was stripped of his Humanist of the Year award for similar anti-Trans sentiments. All of these people are progressives, either of the liberal or socialist variety, the difference matters little, but their fall from grace in the eyes of their fellow progressives demonstrates the inevitable obsolescence innate to their belief system. How long will it be until the fully updated progressives of 2021 are replaced by a newer model?

On a broader scale, we can think of it in terms of generational divides regarding social attitudes, where the boomers and Generation X are often characterised as the conservatives pitted against the liberal millennials and Generation Z. Yet during the childhood of the boomers, the United Nations was established and adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and when they hit adolescence and early adulthood the sexual revolution had begun, with birth control widespread and both homosexuality and abortion legalised. Generation X culture emerged when all this was fully formed, and rebelled against utopian boomer ideals and values in the shape of punk rock, the New Romantics, and mass consumerism. If the boomers were, and still are, ceaselessly optimistic, Generation X on the other hand are tiringly cynical. This trend predictably continued, millennials rebelled against Generation X and Generation Z rebelled against millennials. All of them had their progressive shibboleths, and all of them were made obsolete by their successors. To a liberal Gen Zer in 2021, it seems unthinkable that will one day be the crusty boomer, but Generation Alpha will no doubt disagree.

Since 2010, Apple’s revolutionary iPad has had 21 models, but the current could only look on in awe at the sheer number of different versions of progressive which have been churned out since the age of Enlightenment. As an object, the iPad has no choice in the matter. Tech moves fast, and its creators build it with the full knowledge it will be supplanted as the zenith of Apple’s capabilities within two years or less. The progressives on the other hand are inadvertently supportive of their inevitable obsolescence. Just as they were eager not to let the supremacy of their ancestors’ ideas linger for too long, lest the insatiable agitation of Whiggery be halted for a moment, their successors hold an identical opinion of them. Their imperfect human sluggishness will leave them consigned to the dustbin of history, piled in with both the traditionalism they so detested as well as the triumphs of liberalism that didn’t quite get with the times once they were accepted as given. Like Ozymandias, who stood tall over the domain of his glory, they too are consigned to a slow burial courtesy of the sands of time.

As much as planned obsolescence is a regrettable part of modern technology, so too is it an inescapable component of liberalism. Any idea, concept, or structure can only last for a given time period before it is torn down or has its nature drastically altered beyond recognition to stop it forming into a new despotic custom. Without reference to being, the world and its products are left purely in the hands of mankind. Defined by caprice, “freedom”, “equality”, or “democracy” can be given just as quickly as they can be taken, with little justification required other than the existing definition requiring amendment. Who decides the new meaning? And what happens to those who defend the existing one? Irrelevant, for one day both will be relics, and so too shall the ones that follow it. What happens when there is no more progress to be made? Impossible to say for certain, but if we are to take example from nature, a tornado once dissipated leaves behind only eerie silence and a trail of destruction, from which the only answer is to rebuild.

Post Views: 1,097